For LGBTQ People, Recent Anti-Discrimination Advances Could Lessen Barriers to Economic Inclusion

End Notes

[1] Emanuella Grinberg, “How the Stonewall riots inspired today’s Pride celebrations,” CNN, June 28, 2019, https://www.cnn.com/2019/06/28/us/1969-stonewall-riots-history/index.html.

[2] Sharita Gruberg, Lindsay Mahowald, and John Halpin, “The State of the LGBTQ Community in 2020,” Center for American Progress (CAP), October 6, 2020, https://www.americanprogress.org/article/state-lgbtq-community-2020/.

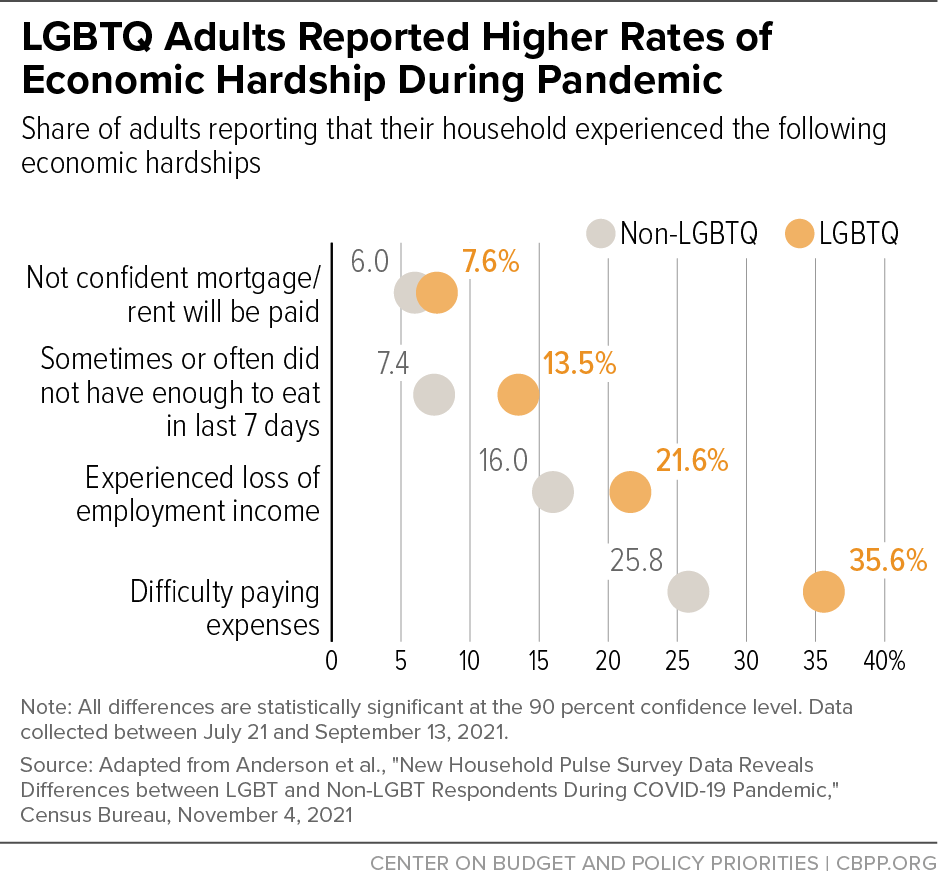

[3] Lydia Anderson et al., “New Household Pulse Survey Data Reveals LGBT and Non-LGBT Respondents During COVID-19 Pandemic,” Census Bureau, November 4, 2021, https://www.census.gov/library/stories/2021/11/census-bureau-survey-explores-sexual-orientation-and-gender-identity.html.

[4] See e.g. M.V. Lee Badgett, Soon Kyu Choi, and Bianca D.M. Wilson, “LGBT Poverty in the United States,” Williams Institute, University of California, Los Angeles School of Law, October 2019, https://williamsinstitute.law.ucla.edu/publications/lgbt-poverty-us/.

[5] Gruberg, Mahowald, and Halpin, op. cit.; Caroline Medina et al., “The United States Must Advance Economic Security for Disabled LGBTQI+ Workers,” CAP, November 3, 2021, https://www.americanprogress.org/article/united-states-must-advance-economic-security-disabled-lgbtqi-workers/.

[6] Williams Institute, “Race and Well-Being Among LGBT Adults,” https://williamsinstitute.law.ucla.edu/visualization/lgbt-races/.

[7] Shoshana K. Goldberg and Kerith J. Conron, “LGBT Adult Immigrants in the United States,” Williams Institute, February 2021, https://williamsinstitute.law.ucla.edu/publications/lgbt-immigrants-in-the-us/.

[8] Badgett, Choi, and Wilson, op. cit.

[9] Medina et al., op. cit.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Data cited in this section uses “transgender” as an umbrella term to include people whose gender is not (exclusively) the one that they were assigned at birth. This term includes people who identify as trans men and trans women, as well as people who identify as non-binary.

[12] Badgett, Choi, and Wilson, op. cit.

[13] Gruberg, Mahowald, and Halpin, op. cit.; Sandy E. James et al., “The Report of the 2015 U.S. Transgender Survey,” National Center for Transgender Equality, December 2016, https://transequality.org/sites/default/files/docs/usts/USTS-Full-Report-Dec17.pdf.

[14] American Civil Liberties Union, “Legislation affecting LGBTQ rights across the country,” updated June 17, 2022, https://www.aclu.org/legislation-affecting-lgbtq-rights-across-country.

[15] Lourdes Ashley Hunter et al., “Intersecting Injustice: Addressing LGBTQ Poverty and Economic Justice for All: A National Call to Action,” Social Justice Sexuality Center, City University of New York, March 2018, https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5a00c5f2a803bbe2eb0ff14e/t/5aca6f45758d46742a5b8f78/1523216213447/FINAL+PovertyReport_HighRes.pdf.

[16] James et al., op. cit.

[17] Gruberg, Mahowald, and Halpin, op. cit.

[18] U.S. Department of State, “X Gender Marker Available on U.S. Passports Starting April 11,” March 31, 2022, https://www.state.gov/x-gender-marker-available-on-u-s-passports-starting-april-11/; Movement Advancement Project, “Equality Maps: Identity Document Laws and Policies,” updated June 23, 2022, https://www.lgbtmap.org/equality-maps/identity_document_laws.

[19] Ibid.

[20] Beth Schwartzapfel, “What’s in a Name?” Marshall Project, January 27, 2020, https://www.themarshallproject.org/2020/01/27/what-s-in-a-name.

[21] Hunter et al., op cit.

[22] Wendy Sawyer, “Visualizing the racial disparities in mass incarceration,” PPI, July 27, 2020, https://www.prisonpolicy.org/blog/2020/07/27/disparities/.

[23] Bostock v. Clayton County, https://www.law.cornell.edu/supremecourt/text/17-1618.

[24] Christy Mallory, Luis A. Vasquez, and Celia Meredith, “Legal Protections for LGBT People After Bostock v. Clayton County,” July 2020, https://williamsinstitute.law.ucla.edu/publications/state-nd-laws-after-bostock/.

[25] White House, “Executive Order on Preventing and Combating Discrimination on the Basis of Gender Identity or Sexual Orientation,” January 20, 2021, https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/presidential-actions/2021/01/20/executive-order-preventing-and-combating-discrimination-on-basis-of-gender-identity-or-sexual-orientation/.

[26] Gruberg, Mahowald, and Halpin, op. cit.

[27] Lindsey Dawson et al., “LGBT+ People’s Health and Experiences Accessing Care,” Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF), July 22, 2021, https://www.kff.org/womens-health-policy/report/lgbt-peoples-health-and-experiences-accessing-care/.

[28] Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, 42 USC § 18116 (2010).

[29] Office of Civil Rights, Department of Health and Human Services, “Notification of Interpretation and Enforcement of Section 1557 of the Affordable Care Act and Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972,” May 10, 2021, https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/ocr-bostock-notification.pdf.

[30] Ibid.

[31] MaryBeth Musumeci et al., “Recent and Anticipated Actions to Reverse Trump Administration Section 1557 Non-Discrimination Rules,” KFF, June 9, 2021, https://www.kff.org/racial-equity-and-health-policy/issue-brief/recent-and-anticipated-actions-to-reverse-trump-administration-section-1557-non-discrimination-rules/.

[32] Ann Oliva, “Ending Homelessness: Addressing Local Challenges in Housing the Most Vulnerable,” CBPP, Testimony before the House Financial Services Committee, Subcommittee on Housing, Community Development and Insurance, February 2, 2022, https://www.cbpp.org/research/housing/ending-homelessness-addressing-local-challenges-in-housing-the-most-vulnerable; Bianca D.M. Wilson et al., “Homelessness Among LGBT Adults in the US,” Williams Institute, May 2020, https://williamsinstitute.law.ucla.edu/publications/lgbt-homelessness-us/.

[33] Assistant Secretary for Fair Housing and Equal Opportunity, U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, “Implementation of Executive Order 13988 on the Enforcement of the Fair Housing Act,” February 11, 2021, https://www.hud.gov/sites/dfiles/PA/documents/HUD_Memo_EO13988.pdf.

[34] Diane K. Levy et al., “A Paired-Testing Pilot Study of Housing Discrimination against Same-Sex Couples and Transgender Individuals,” Urban Institute, June 30, 2017, https://www.urban.org/research/publication/paired-testing-pilot-study-housing-discrimination-against-same-sex-couples-and-transgender-individuals.

[35] National Alliance to End Homelessness, “HUD’s Equal Access Rule,” updated April 2021, https://endhomelessness.org/resource/huds-equal-access-rule/.

[36] Kathryn K. O’Neill, Bianca D.M. Wilson, and Jody L. Herman, “Homeless Shelter Access Among Transgender Adults,” Williams Institute, November 2020, https://williamsinstitute.law.ucla.edu/publications/trans-homeless-shelter-access/.

[37] Anderson et al., op. cit.

[38] Taylor N.T. Brown, Adam P. Romero, and Gary J. Gates, “Food Insecurity and SNAP Participation in the LGBT Community,” Williams Institute, July 2016, https://williamsinstitute.law.ucla.edu/publications/lgbt-food-insecurity-snap/.

[39] Kerith J. Conron and Kathryn K. O’Neill, “Food Insufficiency Among Transgender Adults During the COVID-19 Pandemic,” Williams Institute, April 2022, https://williamsinstitute.law.ucla.edu/publications/trans-food-insufficiency-covid/.

[40] Ibid.

[41] Civil Rights Division, Food and Nutrition Service, U.S. Department of Agriculture, “Application of Bostock v. Clayton County to Program Discrimination Complaint Processing – Policy Update,” May 5, 2022, https://www.fns.usda.gov/cr/crd-01-2022.

[42] White House, “Fact Sheet: President Biden to Sign Historic Executive Order Advancing LGBTQI+ Equality During Pride Month,” June 15, 2022, https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2022/06/15/fact-sheet-president-biden-to-sign-historic-executive-order-advancing-lgbtqi-equality-during-pride-month/.

[43] Human Rights Campaign Foundation, “The Lies and Dangers of Efforts to Change Sexual Orientation or Gender Identity,” https://www.hrc.org/resources/the-lies-and-dangers-of-reparative-therapy.

[44] Jabari Cook, “Congress Should Support LGBTQ People With Low Incomes by Expanding the Child Tax Credit and Earned Income Tax Credit,” CBPP, June 23, 2022, https://www.cbpp.org/blog/congress-should-support-lgbtq-people-with-low-incomes-by-expanding-the-child-tax-credit-and.

[45] Sarah Lueck, “Economic Legislation Should Include Health Policies to Boost Coverage, Ease Strain on Families’ Budgets,” CBPP, March 21, 2022, https://www.cbpp.org/blog/economic-legislation-should-include-health-policies-to-boost-coverage-ease-strain-on-families.

[46] Will Fischer, “President’s Budget Would Provide More Vouchers to Help Families With Rising Housing Costs,” CBPP, April 20, 2022, https://www.cbpp.org/blog/presidents-budget-would-provide-more-vouchers-to-help-families-with-rising-housing-costs.

[47] Sharon Parrot, “Murray-Kaine Proposal to Expand, Improve Child Care Would Benefit Families and the Economy,” CBPP, May 18, 2022, https://www.cbpp.org/research/federal-budget/murray-kaine-proposal-to-expand-improve-child-care-would-benefit-families.

[48] Kathleen Romig and Sam Washington, “Policymakers Should Expand and Simplify Supplemental Security Income,” CBPP, updated May 4, 2022, https://www.cbpp.org/research/social-security/policymakers-should-expand-and-simplify-supplemental-security-income.

[49] Ed Bolen, “Time’s Up for SNAP’s Time Limit,” CBPP, July 7, 2021, https://www.cbpp.org/blog/times-up-for-snaps-time-limit.

[50] Darrel Thompson and Ashley Burnside, “No More Double Punishments: Lifting the Ban on SNAP and TANF for People with Prior Felony Drug Convictions,” Center for Law and Social Policy, updated April 2022, https://www.clasp.org/publications/report/brief/no-more-double-punishments/.