While the economic package that Congress and the White House may craft in coming weeks is expected to be considerably smaller than legislation the House passed late last year, expanding child care so that more families can afford and obtain quality care should be a high priority in the package. A new proposal released by Senators Patty Murray and Tim Kaine[1] would increase the number of families in every state who can afford child care, improve the quality of child care in every state, and establish a pilot program so that some states can test how to create a more robust system that provides a larger group of low- and middle-income children who need it with access to affordable child care. The core of the proposal — increased funding that goes to every state — would increase the number of children receiving child care assistance by more than 1 million children, according to estimates by the Center for Law and Social Policy, while also expanding the supply of child care.[2]

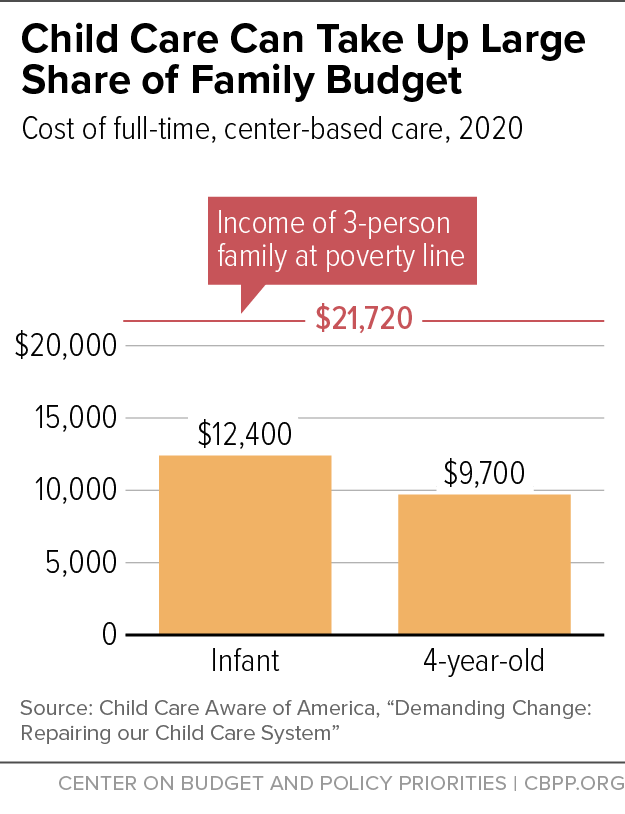

Child care is expensive. The average cost of center-based care for a toddler exceeded $10,000 in a majority of states in 2020.[3] The burden of affording child care falls especially hard on families with young children, since the parents tend to be younger and thus to earn less than they will later in their careers. Despite the high cost of child care, the people who provide child care often are paid low wages, making it hard for them to make ends meet and contributing to high turnover in the industry.

The proposal would increase funding both for child care subsidies for families and for efforts to increase the supply and quality of child care and improve child care workers’ wages. It would have important, tangible benefits:

- Helping more parents work. Parents who have access to affordable, quality child care are better able to rejoin or remain in the labor force and work, yet federal funding to help families afford child care is severely inadequate. Pre-pandemic, only about 1 in 7 children whose families were eligible for child care assistance received it.[4] Expanding both the number of families with child care subsidies and the supply of child care so families can find care would make it possible for more parents to work.

- Improving the economy by expanding the labor force. Enabling more parents to work can help employers find workers they need by raising the labor force participation rate, which has risen since the worst of the pandemic but remains below historical highs for prime-age adults (ages 25-54). Moreover, raising the labor force participation rate can help ease inflation pressures modestly by increasing the economy’s capacity to supply goods and services and accommodate a higher level of consumer demand without adding to inflation.

- Easing strain on family budgets. Expanding child care assistance would help families facing difficulties due to rising costs for necessities like rent, food, and energy. For families newly receiving child care subsidies, child care costs would take up a far smaller share of their budgets than they do now. And, by making it possible for more parents to work, families’ incomes will increase. Parents can also earn higher hourly wages over time because when workers have a longer, steadier work history, the amount they are paid for their work rises.

- Supporting children’s healthy development. Research shows that high-quality child care and pre-K put children on a good path for success in school. Raising family incomes has positive long-term impacts on children’s health and education outcomes as well.

- Improving the wages of child care workers. The proposal includes funds that can be used to help pay higher wages to child care workers. This would not only help workers, who are disproportionately women of color, but also help providers absorb increased labor costs they may be facing now due to tight labor markets.

Without a robust new investment in child care, parents are likely to face increasing difficulty finding and affording child care. The labor market is tight overall and demand for child care is likely to rise as more people return to work, yet many current or prospective child care workers have job opportunities in other industries. Indeed, the number of child care workers fell by 11 percent between 2011 and 2019, and the pandemic accelerated job losses in this sector.[5] As wages are pushed up in other jobs, child care providers in many communities will either have to raise wages to find and retain workers (which would force them to charge families more) or reduce their workforce by having fewer classrooms in their programs or closing their doors entirely — both of which would reduce supply and make it harder for families to find care. In the absence of new funding for child care subsidies, supply investments, and boosting wages, more parents would likely be unable to work or would have to work less, and more parents could be forced to rely on a patchwork of informal care.

A significant investment in child care funding can help. The increased funding in the Murray-Kaine proposal could be used to help meet the higher labor costs child care providers need to pay — either to find and retain workers or to ensure that their workers are paid reasonable wages for a difficult and important job. It would also enable more families to get child care subsidies, which can make the difference in their ability to afford child care and allow more parents to work or work more.

Inflation fears shouldn’t block policymakers from enacting a well-designed economic recovery package that includes the Murray-Kaine proposal. A package that invests in child care as well as in areas like energy and health care, while at the same time raising revenues and reducing the deficit, would have little, if any, impact on aggregate demand and thus does not raise significant inflationary concerns.[6]

The House-passed Build Back Better package included a far-reaching child care plan that sought to ensure that low- and middle-income families would pay no more than 7 percent of their income for child care (low-income families would pay substantially less) and that would raise child care quality substantially. The proposal’s cost, however, likely exceeds what a scaled-back economic package can accommodate. Moreover, that plan faced concerns that some states would choose not to participate fully in the new program because of the costs they would bear.

Senators Patty Murray and Tim Kaine, chair and member of the Senate Health, Education, Labor and Pensions committee, respectively, have unveiled a new proposal that can fit within a smaller economic package. It would allow every state to make important improvements to its child care system and help substantially more families pay for child care than get help today.

The proposal would increase funding for the Child Care and Development Block Grant (CCDBG) — the nation’s main child care program — by $12 billion per year over the next six years.[7] Of this amount, $3 billion per year would be dedicated to Supply and Compensation Grants to “open new child care providers, support increased compensation for early childhood educators, and ensure child care facilities are safe and developmentally appropriate for children.”[8] These grants are designed in part to raise the number of child care providers available to meet demand while improving the quality of care, which is critical to maximizing positive impacts for children.

The added $12 billion would not require a state match. As they are today, states would be free to put in additional state funding at their option, which would allow them to implement a larger expansion of their child care assistance program.

In 2019, state child care programs spent a total of about $10 billion[9] (including both federal and state child care funds as well as Temporary Assistance for Needy Families funds that states transferred to child care) and served about 1.4 million children, according to data from the Department of Health and Human Services.[10] The additional CCDBG funding in the Murray-Kaine proposal would increase the number of children served by more than 1 million, the Center for Law and Social Policy estimates.[11]

At the same time, the proposal’s quality and supply investments — which include funding to help defray higher wage costs for workers and efforts to increase the number of child care providers and classrooms open — coupled with more adequate funding for child care subsidies, would help expand the number of child care providers, lift child care quality, and improve pay for child care workers. These investments would help children who don’t receive child care subsidies as well as those who do. They would accomplish this by improving the quality of care provided in programs that receive the additional resources, by making it easier for parents with and without subsidies to find care, and by reducing the risk that the supply of child care continues falling just when the economy needs more workers.

The proposal would also create a pilot to allow a set of states to test how to set up a child care system that ensures that a broader set of low- and middle-income families don’t pay more than 7 percent of their income for child care for children under age 6; participating states would test how to scale up this broader-based system, build adequate supply, and improve quality. Most children would be eligible to participate and their families would pay on a sliding scale, so families with higher incomes would pay a larger share of their income than lower-income families. The federal government would pay 90 percent of the costs under the pilot, with states contributing 10 percent.

The proposal includes two further provisions: $12 billion over six years to increase pay for Head Start workers and $18 billion over six years for states to expand high-quality pre-K programs for 3- and 4-year-olds. The Head Start funding would help programs retain workers and help hardworking teachers and support staff make ends meet. The pre-K funding would enable states to continue to build out their preschool offerings. While states have invested their own resources in pre-K, including programs run through public school systems and those through private providers, few states have universal public pre-K for all 3- and 4-year-olds. The funding provided here would not be sufficient to reach the goal of universal pre-K for all of these children, but it would help states continue to expand pre-K.

The Murray-Kaine proposal would help states build on the investments they are making in their child care systems through funding provided by both the December 2020 COVID relief package and the March 2021 American Rescue Plan.

Many child care providers saw their revenues plummet during the pandemic, as programs had to shut down temporarily and many families pulled their children out due to pandemic-related health concerns or inability to afford care. States have used the COVID relief funding to help child care programs stay in business, reopen, or open for the first time; help more families afford child care; and increase the amount child care providers receive to care for children so they can, among other things, improve wages for child care workers and improve program quality.[12]

Surveys by the National Association for the Education of Young Children have shown that these investments are helping child care providers stay open, increase pay, and pay down debt. For example, in an online survey of nearly 5,000 child care providers in January 2022, most indicated that they (or the provider they worked for) had received relief funding, and a large share of those who had received funding reported that it helped them remain open, improve worker pay, and reduce debt.[13]

States are also using child care-related relief funding to reduce child care costs for families, such as by waiving co-payments, and to provide more families with child care assistance.[14]

But the relief funding is temporary and designed to meet immediate needs related to the pandemic and its economic fallout. Longer-term child care funding is needed to expand access to child care assistance and improve supply and quality into the future.

Without child care, some parents — overwhelmingly women — are unable to work entirely or must limit the number of hours they work, often hurting not only their immediate earnings but also their long-term earnings trajectories.[15] When parents continue to work but don’t have access to affordable, quality care, they often rely on make-do, unstable child care arrangements that may lead to lost work hours, increased familial stress, and worse outcomes for children.[16]

Prior to the pandemic, federal child care subsidies served only about 1 in 7 eligible children due to lack of funding.[17] In 2020, nearly 100,000 eligible children were on waiting lists for subsidies in states that kept them; other states have stopped accepting new children altogether.[18] Studies have documented that a significant share of families on these waiting lists lost or quit their jobs while they waited.[19] Without subsidies, many families simply cannot afford child care. (See Figure 1.)

Families of color face particular challenges affording and accessing child care. Because of systemic racism, more families of color than white families have low incomes that make affording high-quality care difficult or impossible, and many communities of color, particularly Native American and Latino communities, live in areas with a dearth of child care providers.[20]

But the good news is that we know that helping families afford quality child care — and ensuring an adequate supply of care — can help more parents work, improve the economy by expanding the labor force, strengthen family budgets, and support children’s healthy development.

A recent literature review found that reducing the cost of child care boosted maternal employment, with stronger effects on the employment of single mothers, mothers with younger children, and mothers with low incomes.[21] An Urban Institute study found that, when controlling for other differences, states that spend more on child care assistance have higher employment rates for mothers with low incomes.[22]

By helping more parents work, expanding access to affordable child care can expand the economy as well. While the labor market overall has rebounded robustly since the early days of the pandemic when tens of millions of people lost jobs, the share of non-elderly adults who are either working or looking for work has not yet fully recovered to pre-pandemic levels, which themselves were still below the peak post-World War II rates experienced in the 1990s expansion. Expanding access to affordable, quality child care can raise labor force participation and that, in turn, would increase the economy’s capacity to supply goods and services and accommodate a higher level of consumer demand without adding to inflation.

Child care assistance also improves family budgets because it reduces the high cost burden of child care and can lead to better employment outcomes, which translates into higher earnings. The resulting income gains for families can help children achieve better long-term outcomes.

Children also benefit more directly from improved access to quality child care. A 20-year longitudinal study of children with varying care arrangements in early childhood found that attending high-quality child care was consistently associated with higher performance on standardized tests and cognitive measurements at four periods of time ranging from ages 3 to 15.[23] Attending high-quality child care was also associated with higher grades and plans to attend a more selective college once children reached adolescence.[24] Research further suggests that positive results from child care are likelier for low-income children.[25]

But quality matters. Research has shown that low-quality care can negatively affect children. That is why it is critical to both expand child care assistance and raise the quality of care provided, by increasing pay for caregivers (to reduce turnover and attract skilled caregivers), ensuring adequate training, investing in facilities and materials that children need for healthy development, and providing adequate oversight of child care providers.

As noted above, the Murray-Kaine proposal would also provide funding to states to expand pre-K programs. These resources are needed; state-funded pre-K programs enrolled only 34 percent of 4-year-olds and 6 percent of 3-year-olds in 2019-2020.[26] (Children often participate in pre-K programs that operate for fewer hours than parents work each day and then receive child care services so parents can work a full workday; child care programs can also fill in during the summer, when many pre-K programs are closed. In other models, pre-K is provided by full-day, full-year providers.)

Robust research demonstrates the positive long-term results from effective pre-K programs. Randomized control trials of small pre-K programs that tracked children over decades show robust effects on high school graduation rates, college enrollment, and adult earnings.[27] Notable research on programs operating at scale, including Head Start and Boston’s citywide preschool initiative, has also shown lasting gains for children.[28] For example, students who won a lottery to enter Boston’s city-wide preschool program went on to achieve an 8 percentage point (18 percent) gain in on-time college enrollment and a 5.5 percentage point gain in on-time enrollment in a four-year college. Although findings are not uniform,[29] a preponderance of evidence suggests lasting gains for children from quality pre-K programs.[30]

With pre-K as with child care, quality matters, so it will be critical that states invest not only in expanding access but also in assuring high quality.

Some have raised concerns that an economic package could cause further inflationary pressure in the economy, but a package that combines targeted investments with deficit reduction and spreads its spending and tax increases relatively evenly over the decade shouldn’t raise inflation concerns.

Such a package would not significantly affect aggregate demand, which is the main driver of recent inflation (other than issues related to the Russian invasion of Ukraine, which is raising prices of certain commodities). And investments that expand the labor force over the near or long term, like expanding access to affordable child care, reduce inflationary pressures associated with a shortage of available workers.

In addition, while the Murray-Kaine proposal would increase the demand for child care (by boosting the subsidies that make it affordable for many families), it would also expand the supply of child care, which would reduce inflationary pressures within the child care market.