Thank you for the opportunity to testify today on this timely and important topic. My name is Ann Oliva; I am the Vice President for Housing Policy at the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. The Center is an independent, nonprofit policy institute that conducts research and analysis on a range of federal and state policy issues affecting low- and moderate-income individuals and families. The Center’s housing work focuses on increasing access to and improving the effectiveness of federal low-income rental assistance and homelessness programs. Prior to coming to the Center, I spent ten years as a senior career public servant at the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), most recently as Deputy Assistant Secretary for Special Needs. At HUD, I oversaw the Department’s homelessness and HIV/AIDS housing programs and helped to design and implement the HUD-VA Supportive Housing (HUD-VASH) program.

The nation is experiencing a homelessness crisis, one that predated the pandemic and will continue to worsen without continued intervention. In January 2020 — before the pandemic — 30 states across America saw a rise in homelessness from one year earlier and, for the first time since we began tracking this data, more single individuals[1] experiencing homelessness were unsheltered than sheltered and there were more people in families living unsheltered than the year prior.[2] Living on the streets is a brutal existence for men, women, families, and youth, and negatively impacts not only the people forced to live in these conditions but also the surrounding neighborhoods and communities. But shelters are far from ideal as well. Shelters feature only short-term stays, and congregate settings can exacerbate health conditions rather than providing the kind of help people need to obtain housing. During the pandemic, congregate shelters have been especially problematic, as they can facilitate the spread of COVID-19.

But the pandemic also has showed us that long-term change is possible with investments in permanent and supportive housing. Substantial investments made as part of the nation’s pandemic response — including in the Emergency Solutions Grants-COVID (ESG-CV) program, the Emergency Rental Assistance (ERA) Program, Emergency Housing Vouchers, and the HOME Investments Partnerships program — are helping communities to keep families experiencing instability housed and providing critical resources for families, youth, and individuals already experiencing homelessness.

Over 3.2 million households received emergency rental assistance from January to November 2021, according to Treasury Department data[3] which is credited with keeping the eviction rate lower than expected after the end of the national eviction moratorium. The first allocation of ERA funds (called ERA-1) is providing well-targeted assistance — nearly 9 in 10 (88 percent) of the households served through September, excluding households served by tribes, have incomes at or below 50 percent of the area median income. HUD reports that the Emergency Housing Voucher program — still in early stages of implementation — has issued more than 22,000 vouchers to households experiencing or at risk of homelessness and more than 9,000 units have already been leased.[4] ESG-CV has helped communities respond to the needs of people living unsheltered and in shelters, and HOME will help communities build permanent and supportive housing.

This approach — aligning emergency responses with longer-term supply side investments and rental assistance resources — will help communities execute comprehensive plans to address local needs. These resources are the right start, but more investment on an ongoing, rather than temporary, basis ultimately will be needed to build on the successes of these relief measures and fully address the homelessness crisis described in this testimony.

I want to thank this committee for its work on housing-related relief measures over the course of the pandemic, including in the bipartisan CARES Act and December 2020 relief package as well as the homelessness funding provided as part of the American Rescue Plan Act. I also want to thank Chairwoman Waters and Representatives Cleaver and Torres for their work on the Ending Homelessness Act of 2021, which would build on the investments made over the last two years and make bold changes to strengthen communities and improve the lives of those who are experiencing homelessness or at risk of homelessness. Expanding the Housing Choice Voucher program to provide a voucher to every eligible household, as this legislation would do, is the single most important step we can take to address the homelessness crisis. Congress should also enact the House’s current fiscal year 2022 appropriations proposal for a 125,000-voucher increase and pass a large-scale, multi-year voucher expansion like the one included in the House-passed Build Back Better Act to make progress toward ending homelessness.

After a brief examination of the current national landscape on homelessness and housing instability, my testimony today will discuss:

- challenges facing homeless services providers and people experiencing homelessness in accessing housing and services;

- important legislative efforts;

- why universal vouchers are the most important step we can take toward ending homelessness;

- how voucher expansion would advance equity for historically marginalized people;

- how voucher expansion can reduce homelessness most effectively, based in part on recent discussions with people with lived experience of homelessness and voucher use; and

- how voucher expansion can increase opportunities for both preventing and exiting homelessness.

National Landscape on Homelessness and Housing Instability

HUD reports that more than 580,000 people (including members of families as well as individuals) were experiencing homelessness on a single night in January 2020, prior to the COVID-19 pandemic.[5] Sixty-one percent were in sheltered locations, while 39 percent were unsheltered. They included nearly 172,000 people in families (60 percent of them children), more than 110,500 people experiencing chronic homelessness,[6] and more than 37,000 veterans. Over the course of a year, nearly 1.45 million people experience sheltered homelessness at some time.[7]

These 2020 point-in-time data illustrate two significant shifts in the landscape of homelessness that were underway prior to the pandemic:

- Homelessness increased in 30 states. Unlike in prior years, between 2019 and 2020 the number of people experiencing homelessness increased in more states than it decreased.

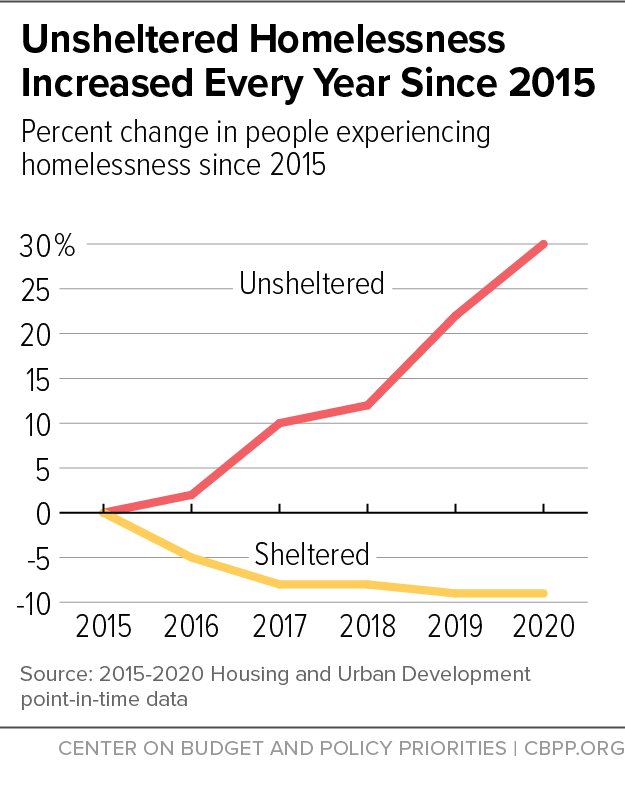

- Unsheltered homelessness is at crisis levels. Unsheltered homelessness (which is less common among families with children) has increased every year since 2015. (See Figure 1.) In 2020, for the first time since the count began, there were more unsheltered single individuals (51 percent) than sheltered single individuals (49 percent) and there were more unsheltered people in families with children than the year prior. Between 2019 and 2020, unsheltered homelessness among white people increased 8 percent, while increases among Black and Hispanic/Latino people were 9 and 10 percent, respectively.

Recent data from the Census Bureau’s Pulse Survey demonstrate the continued challenges families are facing to secure and afford stable housing during the pandemic as well as the outsized burden experienced by people of color, as well as children and seniors. Data collected between December 1-13, 2021 show that almost 12 million adult renters were behind on rent payments, and more than 40 percent of those renters reported that eviction is either very or somewhat likely to occur in the next two months.[8] Throughout the pandemic, renters of color were more likely to report that their household was not caught up on rent. As of December, 30 percent of Black renters, 21 percent of Latino renters, and 14 percent of Asian renters said they were not caught up on rent, compared to 10 percent of white renters. The rate was 16 percent for American Indian, Alaska Native, Native Hawaiian, Pacific Islander, and multiracial adults taken together. Additionally, 18 percent of renters over 65 reported no or little confidence in their ability to pay next month’s rent and roughly one-quarter of households behind on rent have children.[9]

It is important to understand the needs and characteristics of people experiencing homelessness and housing instability so that interventions can be designed and funded to address those needs.

Families experiencing homelessness are typically headed by women and a large share include young children.[10] About 501,100 people in 156,000 households with children used an emergency shelter or transitional housing in fiscal year 2018. Of those persons, 62 percent were children and nearly 30 percent were children under age 5. Nearly 90 percent of sheltered family households were headed by women.[11]

Youth and young adults experience homelessness as family heads of household and as individuals.[12] In 2018, families with children headed by a parenting young adult aged 18 to 24 accounted for 17 percent of all family households experiencing sheltered homelessness; in addition, 113,330 unaccompanied youth experienced sheltered homelessness during the year. Unaccompanied youth experiencing sheltered homelessness were more likely to be people of color (Hispanic or Latino, Black or African American, multi-racial, or another race other than white) than youth in the general population. LGBTQ youth are at more than double the risk of homelessness compared to non-LGBTQ peers, and among youth experiencing homelessness, LGBTQ young people reported higher rates of trauma and adversity, including twice the rate of early death.[13]

People experiencing unsheltered homelessness have higher needs than sheltered persons and are often engaged by police in harmful ways. The California Policy Lab’s analysis “Health Conditions of Unsheltered Adults in the U.S.” reports that people experiencing unsheltered homelessness are “far more likely to report suffering from chronic health conditions, mental health issues, and experiences with trauma and substance abuse problems as compared to homeless people who are living in shelters.”[14]

Further, the analysis shows that often the “[p]eople with the longest experiences of homelessness, most significant health conditions, and greatest vulnerabilities are not accessing and being served by emergency shelters. Rather than receiving shelter and appropriate care, unsheltered people with major health challenges are instead regularly engaged by police and emergency services.” Relying on emergency systems like ambulances and police departments to respond to homelessness is costly to public systems and traumatizing to individuals experiencing homelessness. It also leads to outcomes like arrests and repeated hospitalizations instead of stable housing and appropriate health care.

People experiencing homelessness often work but still cannot afford housing. The recent paper “Learning about Homelessness Using Linked Survey and Administrative Data” found high rates of formal employment among people experiencing homelessness.[15] The report’s findings not only run counter to pervasive stereotypes about people experiencing homelessness, but also point to the need for a comprehensive and long-term approach to addressing the homelessness crisis:

- Fifty-three percent of adults experiencing sheltered homelessness had formal labor market earnings in the year they were observed as homeless.

- An estimated 40.4 percent of unsheltered persons had at least some formal employment in the year they were observed as homeless.

- However, the “administrative data reveal substantial material deprivation among people experiencing homelessness.” People experiencing homelessness “appear to be having not just a year of deprivation and challenge, but a decade (at least).” In other words, homelessness is a symptom of persistent challenges, poverty, and insecurity.

Inflow into homelessness is significant, and many households are at risk. The homelessness crisis is deeply affected by the number of households entering homelessness from unstable housing situations. HUD’s “Worst Case Housing Needs 2021 Report to Congress” found that nearly 7.8 million households had worst case housing needs[16] and that “the primary problem for worst case needs renters in 2019 was severe rent burden resulting from insufficient income relative to rent.”[17] Research sponsored by Zillow finds that “communities where people spend more than 32 percent of their income on rent can expect a more rapid increase in homelessness.”[18] The lack of affordable housing also underpins the pattern of people entering homelessness from other systems, including child welfare, jails and prisons, emergency rooms, and psychiatric hospitals.

The health and economic impacts of COVID-19 have been far reaching. Many families have experienced losses in earnings and have been unable to pay their rent at various points during the crisis. Policy interventions have helped — evictions fell substantially compared to pre-pandemic levels when the federal eviction moratorium was in place. And although it had a slower start than hoped for, the ERA program (which received almost $50 billion through the December 2020 relief bill and the March 2021 American Rescue Plan), is accelerating assistance to households that need it and keeping millions of households in their homes.

Still, the full need has not been met. The Census Pulse survey continues to show that millions of households are at risk of eviction; people of color continue to be disproportionally impacted; and inherent health risks posed by congregate settings, including nursing homes, jails, and shelters remain.[19] The housing-related relief measures are temporary; thus, further policies and investments will be needed to solve the longer-term problems of housing instability and homelessness.

Through our work on the Framework for an Equitable COVID-19 Homelessness Response project and through one-on-one discussions with industry groups and communities, at least two things seem clear. First, the pandemic-related affordable housing and homelessness funding received to date is having a positive impact and is deeply appreciated by communities that have received it. Second, there is still much work to do toward ending homelessness — both to develop local capacity and to increase affordable and supportive housing for people experiencing homelessness.

As noted earlier in this testimony, the federal government — along with some states and localities — has implemented large-scale measures to mitigate the pandemic’s housing-related fallout through substantial investments to shelter people experiencing homelessness outside of congregate shelters when possible; reduction of evictions through eviction moratoria and emergency rental assistance; and provision of stable housing through emergency housing vouchers and investments to increase the supply of affordable and supportive housing for people experiencing homelessness. The ERA program, which was designed to prevent an eviction crisis, has assisted millions of households — and it is working, as evidenced by lower (though still too high) eviction rates today than prior to the pandemic in many communities for which we have data.[20]

The EHV program is pushing communities to create new or stronger partnerships between homeless services providers and housing authorities so that people experiencing or at risk of homelessness can secure safe and affordable housing. ESG-CV has helped communities respond to the needs of people living unsheltered and support emergency shelters that must respond to shifting environments and health guidance as the pandemic progresses, and the HOME program is helping communities build permanent and supportive housing, a longer-term investment that will improve housing capacity. These investments represent a combination of short-, medium-, and long-term resources that communities are using to address the homelessness crisis, which was growing worse even before the pandemic and has been exacerbated by the health and economic crisis of the last two years.

Even with these new resources, homelessness assistance systems are facing significant challenges. Some are long-standing issues — for example, the scarcity of available supportive and affordable housing units dedicated to people experiencing homelessness makes exiting the homeless system difficult.[21] People often wait for long periods of time in a shelter or on the street before gaining access to a unit and services. And new challenges have also emerged.

- Rising rents are making accessing permanent housing more difficult. Although the wide gap between median renter income and median rent[22] preceded the pandemic, new data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics[23] show a substantial increase in the cost of shelter (housing) and utilities. These increases make it harder for people experiencing housing instability to remain in their units and create housing challenges for people exiting incarceration or institutions like child welfare or hospitals, while also making it more difficult for homeless assistance systems to place people into safe, stable, and affordable housing.

- Pressure to act quickly on several programs at the same time shortened community planning time, which makes implementation challenging. Continuums of care (CoCs) and key partners like nonprofit providers and public housing agencies are under tremendous pressure to quickly implement critical housing-related relief programs and have reported that they do not have adequate time to plan for more equitable or innovative ways to address emerging challenges. In many communities, the recipients of new federal funds are also simultaneously forging new partnerships, as they have not worked with CoCs in the past. The rush to implementation couldn’t be avoided given the urgent nature of the housing issues that arose due to the pandemic and its economic fallout, but as we plan for future policy advances, it is important to recognize the time needed for sound implementation.

- More resources are needed. Even with challenges related to the implementation of new funding streams like the Emergency Housing Voucher program, in a recent (but not yet published) survey by the Urban Institute, communities overwhelmingly reported a need and desire for additional Housing Choice Vouchers to serve people experiencing homelessness. Communities also consistently report a need for better access to services that support people in exiting homelessness.

- Communities are experiencing staffing challenges. Homeless systems — which rely heavily on front-line workers to provide essential services to people experiencing homelessness — report staffing challenges due to the pandemic but also due to long-standing and systemic issues like low pay that create environments with high staff turnover and burnout for the people who work in them.

- Congregate shelters pose risks for residents. Some communities have ended non-congregate sheltering programs that were established in response to the pandemic and have returned residents to congregate shelters, which are often overwhelmed and have proven to be unsafe environments during the pandemic, especially for people who have underlying health issues.[24]

- Criminalization of people experiencing homelessness is rising. As unsheltered homelessness increases, communities across the country are turning to inhumane practices and laws that criminalize people experiencing homelessness and that make accessing housing more difficult for them in the long run. According to the National Homelessness Law Center, 48 states have at least one law restricting behaviors of people experiencing homelessness and these types of laws continue to gain traction across the country.[25]

Homeless assistance systems alone cannot end homelessness. Some communities are rehousing more households than ever before, even as homelessness continues to increase.[26] The problem requires a comprehensive approach that addresses the large numbers of households that cannot afford rents in their communities because their incomes are too low to afford reasonably priced housing, an insufficient supply of reasonably priced housing, or both. The approach must also address access to services for people who need and want them.

The most effective policy we could take to address the nation’s homelessness crisis is to provide a Housing Choice Voucher for every eligible household. Vouchers effectively fill in the gap between the cost of rent and utilities and how much a household can afford to pay, ensuring that those with very low incomes can afford housing. This step would fundamentally alter the landscape for people experiencing homelessness, institutionalization, and housing instability, ultimately preventing many stints of homelessness because households with low incomes would be able to afford housing and, thus, would be less likely to fall behind on rent and face eviction. It would lift millions of children out of poverty and improve educational outcomes, help seniors and people with disabilities, and provide youth and young adults with a brighter path to adulthood.[27] This is the goal we should be working toward, even if we cannot get there in one step.

While the House Financial Services Committee may consider several bills this year, two include policy and resource changes that, if enacted, would have significant, long-term impact on people experiencing homelessness and the systems that serve them: the Build Back Better Act and the Ending Homelessness Act.

The Build Back Better (BBB) Act passed by the House includes $24 billion for housing vouchers that would reduce housing instability for about 300,000 households with the lowest incomes once fully phased in, including families with young children, people with disabilities, and seniors. CBPP estimates that more than 70 percent of people served through this proposed expansion of Housing Choice Vouchers would be people of color, because these households disproportionately have severe housing needs and very low incomes. BBB targets part of its voucher funding to specifically assist about 80,000 households experiencing or at risk of homelessness (including survivors of domestic violence and human trafficking), which would make important progress toward ending homelessness and build upon the work started through the Emergency Housing Voucher program funded as part of the American Rescue Plan Act last year.

An extensive body of research shows that these new vouchers, which would be tightly targeted on families and individuals who need them most, would sharply reduce homelessness, housing instability, and overcrowding. By helping families obtain stable housing, these vouchers would also have other benefits for children (such as a lower likelihood of being placed in foster care, fewer school changes, and fewer sleep disruptions and behavioral problems) and adults (such as lower rates of domestic violence and drug and alcohol abuse). The new vouchers would also help to reduce the large racial disparities in housing opportunity, which reflect long-standing discrimination in housing, employment, and other areas. Some 71 percent of those assisted by the vouchers would be people of color.

BBB also includes key housing investments to help people who have the lowest incomes and who face the greatest challenges in affording stable housing. The bill provides $65 billion to repair and renovate public housing, which would preserve our nation’s public housing stock and improve living conditions for the more than 1.8 million public housing residents by addressing unmet renovation and repair needs that have accumulated for decades.[28] It also provides $25 billion to increase the supply of affordable housing through the national Housing Trust Fund and HOME Investment Partnerships program.

The Ending Homelessness Act of 2021 (the Act) would provide the required comprehensive approach to ending homelessness. Unlike other bills that aim to address homelessness, it would provide critical housing infrastructure through Housing Choice Voucher expansion and investments in the National Housing Trust Fund to address the underlying affordable housing shortage, which is acute in some communities and helps drive increases in homelessness in communities across the country. The legislation would supplement existing programs and would use a variety of funding sources to support an array of eligible activities that address the needs of people who are experiencing sheltered and unsheltered homelessness. The Act would also provide important protections for families and individuals seeking to use vouchers from discrimination based on the source of their income or rental subsidy.

The legislation balances strategies that address affordability, housing supply, services, and technical assistance for communities. It would support significant progress by quickly providing safe and permanent housing through an expansion of the Housing Choice Voucher program to millions of households at the lowest income levels. The Act also includes investments in affordable housing supply where needed. And it includes critical resources for homeless assistance systems to right-size and shift operations so that people living on the street could be rehoused through delivery of outreach and service coordination, coupled with housing that is affordable through the availability of vouchers or other permanent subsidies.

Enacting this approach would fundamentally change the lives of people experiencing homelessness and housing instability. It would allow the homelessness system to be what it always should have been: a response system that quickly rehouses people experiencing a housing crisis, rather than an under-resourced and stretched housing system of last resort for families, youth, people with disabilities, elders, and people returning home from jail or prison.

Expanding Housing Choice Vouchers Is Critical to Ending Homelessness

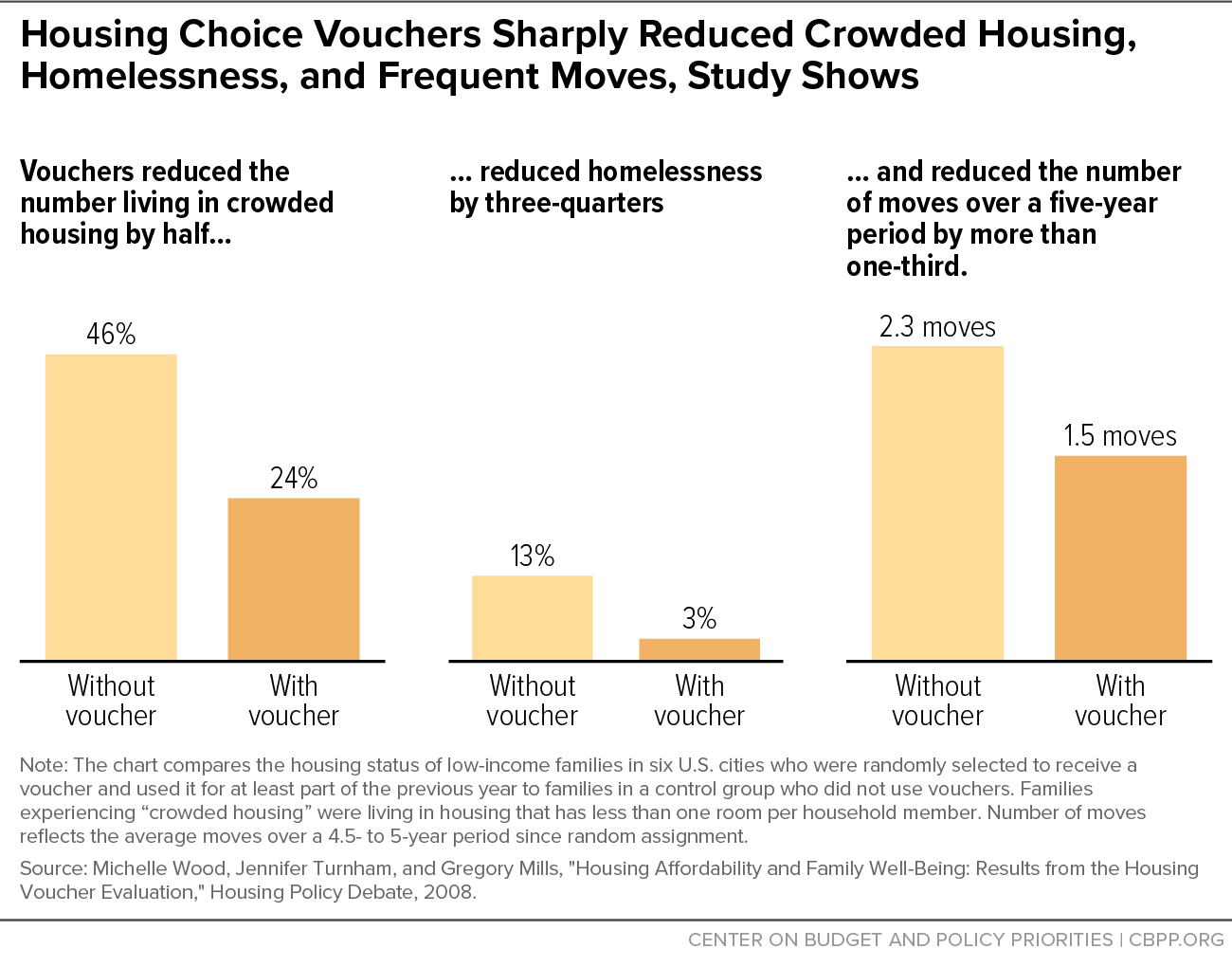

Housing vouchers are highly effective at reducing homelessness, housing instability, and overcrowding and at improving other outcomes for families and children, rigorous research shows. (See Figure 2.)

They are crucial to giving people with low incomes greater choice about where they live and to ensuring that initiatives to build or rehabilitate housing reach those who most need help. Vouchers also make a major contribution to lifting people out of poverty and reducing racial disparities; the housing affordability challenges that vouchers address are heavily concentrated among people with the lowest incomes and, due to a long history of racial discrimination that has limited their economic and housing opportunities, among people of color.[29] (For additional CBPP analysis on the benefits of voucher expansion, see the materials posted at https://www.cbpp.org/research/resource-lists/expanding-housing-vouchers.)

Unfortunately, the Housing Choice Voucher program only reaches about 1 in 4 eligible families due to funding limitations. This shortfall is one of the biggest gaps in the nation’s economic support system and causes families with pressing housing needs to face long waiting lists and homelessness.

Of the 11.2 million renter households with severe cost burdens in 2018, close to three-fourths had extremely low incomes (at or below the federal poverty line or 30 percent of the local median, whichever is higher). Many people cannot afford housing at all and fall into homelessness. Due to a long history of racism — including racially discriminatory housing policies — Black, Latino, and Native American people are disproportionately likely to face severe rent burdens and to experience homelessness.

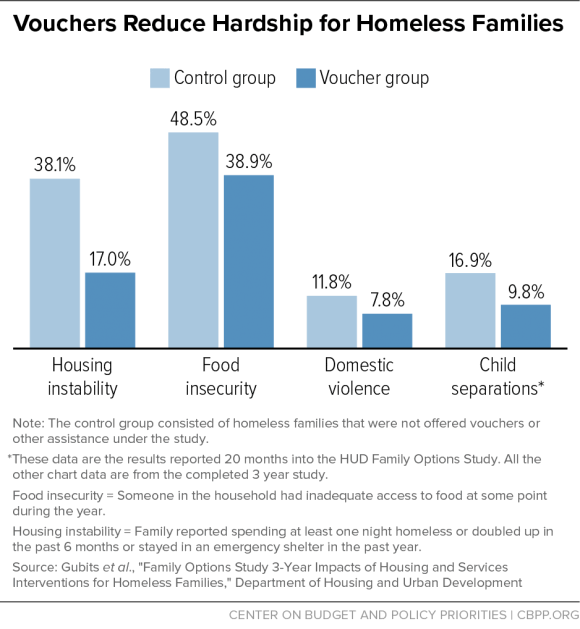

Research including HUD’s Family Options Study and programs like HUD-VASH and the Family Unification Program (FUP) clearly illustrate the potential of expanding the Housing Choice Voucher program for ending homelessness and improving the lives of households with incomes at or near the poverty line.[30] For example, the Family Options Study showed that enrolling in Housing Choice Vouchers improved housing stability and reduced family separations, psychological distress, and alcohol/drug problems for the head of household; intimate partner violence; the number of schools children attended and the number of absences for children; children’s behavioral problems; and food insecurity among families as compared to usual care in the homeless system. (See Figure 4.)

HUD-VASH, which couples services provided by the Veterans Administration with a Housing Choice Voucher to create supportive housing for veterans, was a key resource used to reduce veteran homelessness (especially unsheltered homelessness) by almost half between 2009 and 2020. FUP, which operates as an interagency collaboration between local public housing agencies and child welfare agencies, has been shown to expedite child welfare case closure and support high rates of family reunification for families involved with the child welfare system.[31] FUP can also serve youth aging out of foster care by providing supportive housing for young people who may otherwise experience homelessness or housing instability. [32]

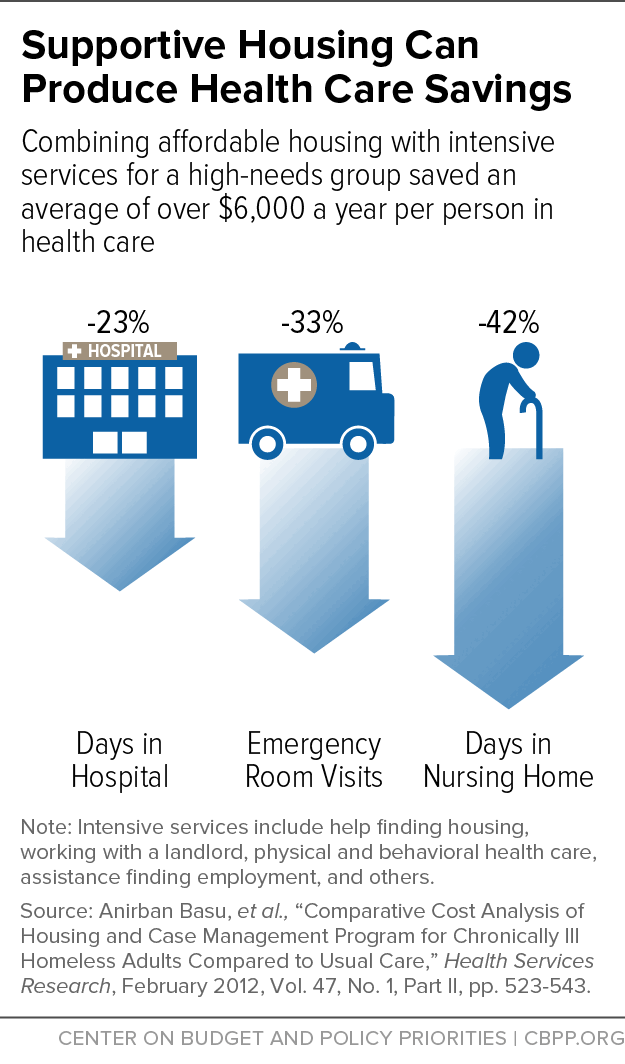

Expanding vouchers is essential to ensuring that people experiencing homelessness who live with disabilities or may be experiencing chronic homelessness can live safely and pursue their goals. Like HUD-VASH, vouchers can be paired with services to develop permanent supportive housing, an evidence-based solution to homelessness among people with disabilities that helps people find and keep housing, which, in turn, can improve health outcomes.[33] Permanent supportive housing can help address long-term homelessness by providing, in combination, affordable housing and voluntary supportive services such as help remembering to take medications and scheduling medical appointments, help understanding a lease agreement, and connections to other health and social services in the community. This coordination of services is critical to addressing housing and health care access barriers that people with disabilities and other complex health needs often experience. States can leverage Medicaid funding to provide services in this model.

Supportive housing can increase opportunities to receive health care in outpatient settings and reduce the need for high-cost health care like emergency room visits and hospitalizations by people experiencing homelessness. People with chronic health conditions experiencing homelessness who received supportive housing spent fewer days in hospitals and nursing homes and had fewer emergency room visits per year, one study found. These reductions in health care utilization resulted in over $6,000 in annual savings per person. (See Figure 5.)

Housing Choice Vouchers can also be project-based to support development of affordable and supportive housing in areas that need increased supply.

The voucher expansion included in the House-passed Build Back Better Act would advance racial equity and equity for other marginalized groups such as people with disabilities and low-income seniors. CBPP estimates that, of the nearly 700,000 people (in 300,000 households) who would benefit from the vouchers in BBB, about 274,000 are children, 138,000 are people with disabilities, and 76,000 are seniors. More than 70 percent of people served through this proposed expansion would be people of color.[34]

People of color are disproportionally affected by homelessness.[35] Nearly 40 percent of those experiencing homelessness in 2020 were Black and 23 percent were Latino, although these groups make up 13 and 18 percent of the U.S. population, respectively.

Voucher expansion would significantly benefit people of color, especially those experiencing homelessness. Insufficient funding prevents vouchers from reaching most people experiencing homelessness, as well as the 24 million people in low-income renter households that pay more than half of their income for rent and utilities. Most of the renters in these households (62 percent) are people of color: 6.8 million are Latino, 5.8 million are Black, 1.4 million are Asian or Pacific Islander, 725,000 are multiracial, and 242,000 are American Indian or Alaska Native. People who pay too much for housing have little money left to cover their basic needs, such as food or medicine. And when finances are stretched precariously thin, an unexpected bill or a reduction in work hours — as many people experienced during the pandemic — can have devastating effects, such as having the heat or electricity cut off or losing one’s home entirely.[36]

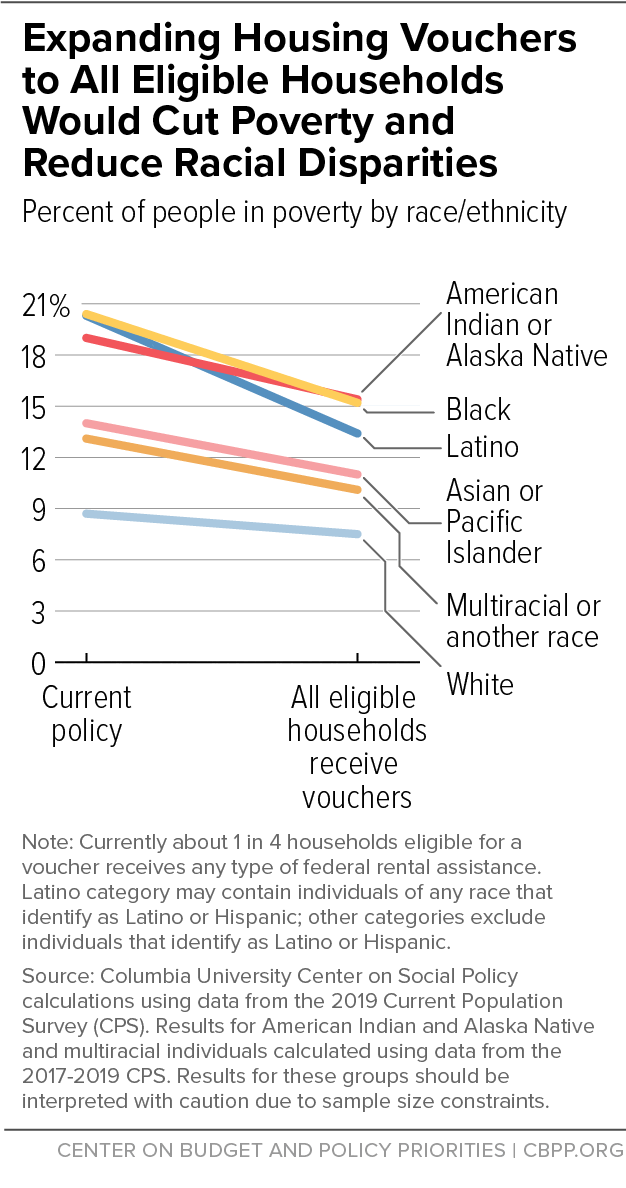

Housing vouchers would help households, both those that are homeless and those facing high rent burdens that place them at risk for eviction and homelessness — obtain and maintain stable, affordable housing and raise their incomes above the poverty line. One study estimated that giving all eligible households vouchers would lift 9.3 million people above the poverty line.[37] These benefits would be greatest among people of color, who would experience the steepest declines in poverty. (See Figure 6.) In particular, expanding vouchers to all eligible households would cut the poverty rate for Latino people by a third, for Black people by a quarter, and by a fifth for Asian people and Pacific Islanders and American Indians and Alaska Natives. Making vouchers available to many additional people would also sharply reduce homelessness, housing instability, and crowding.

Seniors and People With Disabilities

Vouchers are a proven approach that currently deliver major benefits to some 680,000 seniors nationwide — more than any other rental assistance program.[38] A 2019 study, “The Emerging Crisis of Aged Homelessness: Could Housing Solutions Be Funded by Avoidance of Excess Shelter, Hospital, and Nursing Home Costs?”[39] reviewed the ages of people experiencing homelessness and projected significant growth among people aged 65 and older over the next decade. “Older homeless adults have medical ages that far exceed their biological ages. Research has shown that they experience geriatric medical conditions such as cognitive decline and decreased mobility at rates that are on par with those among their housed counterparts who are 20 years older . . . . As a result, health care and nursing home costs are likely to increase significantly over the next 15 years,” the study found. It further recommended permanent housing resources — including the Section 202 program, Housing Choice Vouchers, and Permanent Supportive Housing — to address the housing and service needs of this aging cohort to both improve well-being and reduce costs in physical and behavioral health care, nursing homes, and shelters. However, safe, stable, and affordable housing remains out of reach for millions of older adults and their families, including seniors experiencing homelessness.

Similarly, vouchers deliver major benefits to over 1.2 million disabled people nationwide — more than any other rental assistance program. A broad body of research shows that rental assistance is highly effective at reducing homelessness and helping people maintain housing stability, including among individuals with mental illness, HIV/AIDS, and other complex health conditions. About half of adults — and two-thirds of veterans — living in homeless shelters reported having a disability in 2018. And over three-quarters of people experiencing unsheltered homelessness, which has increased sharply in recent years, report having a physical or mental health condition.[40] Vouchers and other federal rental assistance lift more seniors above the poverty line than any other program except Social Security and Supplemental Security Income.

People with lived experience of homelessness and voucher use must be at the table when policymakers consider topics like affordable housing and homelessness. They bring a critical policy and program design perspective to the discussion based on how these systems actually function, and they make important recommendations based on their experience using these resources. At the launch of the Framework for an Equitable COVID-19 Homelessness Response Project,[41] project leaders asked people experiencing homelessness or housing instability, and those who are among groups that have been historically marginalized, for their input on what challenges should be prioritized and addressed in the nation’s homelessness response systems. Four themes emerged from the discussions and focus groups:

- The most important priority is to address the lack of affordable housing options. Adequate affordable housing options and support (e.g., long-term rental assistance, affordable housing development, services) must be developed and targeted to those most impacted by structural inequity.

- Systems should treat people experiencing homelessness and trauma with dignity. Dignity-based services led by the communities most impacted by homelessness should be designed and supported in a post-COVID environment.

- Congregate shelters should be re-imagined. Current congregate emergency shelter options are often inadequate and can cause further trauma for the people who use them.

- Criminalizing people experiencing homelessness causes harm. Communities should end practices that criminalize people experiencing homelessness, and law enforcement should not be the primary responder when people experiencing homelessness need assistance, because the interactions between law enforcement and people experiencing homelessness are often negative and cause harm.

CBPP also requested recommendations from people with lived expertise of housing instability and challenges on how vouchers can help end homelessness and housing instability.

- Expanding the Housing Choice Voucher program for all eligible households would be a key step toward ending homelessness for many households and preventing homelessness for many others. However, the expansion must be implemented in ways that remove barriers to obtaining and maintaining housing for people with disabilities, immigrant households, those with a history of incarceration, and others. This includes providing more robust support in accessing units by protecting program participants against discrimination based on income source, as the Ending Homelessness Act of 2021 proposes. That legislation would also help voucher holders locate available units and engage with landlords to encourage them to lease to voucher holders. Implementing strategies that support lease-up can cut down the time it takes for a household to lease a unit, especially in tight housing markets.

- Expanding Housing Choice Vouchers would create much-needed changes in the homelessness assistance system. Implementation should be done over time to create a strong foundation for shifting homeless assistance systems out of “crisis mode” and toward functioning as a sustainable system focused on quickly rehousing people who are facing a housing crisis and then helping them achieve stable and permanent housing. It should also create an environment where partners like continuum of care entities and public housing authorities work together to prevent and end homelessness in the community.

- People should not be required to enter a shelter to access a Housing Choice Voucher if they are eligible for the program. Currently, households that may not have otherwise entered a shelter are sometimes required to do so in order to receive a preference for a Housing Choice Voucher, and often must wait months or years for that voucher to become available. In some places, a lottery system to obtain a voucher creates anxiety and uncertainty for those who need affordable housing and may be waiting in a shelter. This also delays the types of benefits that safe and stable housing provides to families, children, and individuals while they wait in a shelter or other precarious situation.

- The maximum rent that a voucher can cover should be reconsidered, especially in tight housing markets. Several participants in the discussion stated that the program’s rent limits are too low in their communities, which makes finding units that meet the requirements more difficult. Implementation of Small Area Fair Market Rents, as required in the Ending Homelessness Act of 2021, would help to ensure that Housing Choice Vouchers more accurately reflect neighborhood rents.

- Both landlords and voucher holders have a role to play. More can be done to connect voucher holders and landlords and to support a positive relationship during tenancy. This may include developing incentives for landlords to participate in the program, increasing access to available units for voucher holders, and implementing strategies (like a risk mitigation fund) that help landlords recover when units are damaged or other crises occur.

We know how to solve homelessness: by providing opportunities for all families and individuals to live in safe and affordable housing that they choose and that meets their needs. To be clear, housing is not the only component of the solution to homelessness. But safe, affordable housing options for the millions of households experiencing or at risk of homelessness must be the core component. We can make significant progress in our national collective efforts to make homelessness rare, brief, and one-time by expanding the Housing Choice Voucher program to all who are eligible.

While voucher expansion is the single most important step policymakers can take to help families afford housing, it is also important to build and rehabilitate affordable housing. But only funding “supply-side” investments, without adequately expanding vouchers, would almost certainly leave out a large share of households that most need help to afford housing. It also would risk constraining the housing choices available to low-income people, people of color, and people with disabilities.

In many parts of the country the number of housing units is generally adequate, and affordability of rent and utility costs is the primary housing problem facing low-income people. In tight housing markets where the number of housing units is inadequate to meet demand and costs are driven up by inadequate supply, more units should be made available by increasing subsidies for constructing affordable housing and rehabilitating affordable housing so it remains on the market and in good condition, and by reducing regulatory barriers to development. In addition, supply-side investments can make units available to assist particular populations, for example by increasing the number of units accessible to people with disabilities. And in some cases, such investments can improve access to neighborhoods where it would otherwise be difficult for people with low incomes to rent homes.

But unless a household also receives a voucher or other similar ongoing rental assistance, construction subsidies for private units rarely produce housing with rents that are affordable for households with incomes around or below the poverty line — which make up most of the renters confronting severe housing affordability challenges. These households typically can’t afford rent set high enough for an owner to cover the ongoing cost of operating and managing housing. Consequently, even if development subsidies pay for the full cost of building the housing, rents in the new units will generally be too high for lower-income families to afford without the added, ongoing help a voucher can provide.

In addition to providing a critical resource to end homelessness as we know it, expanding the Housing Choice Voucher program would provide an important safety net for extremely low-income households and landlords when the nation experiences a crisis. Housing instability became a high-profile national issue during the pandemic, when millions of renters fell behind in rent after job losses, reductions in scheduled hours, or illness. Job losses and reductions in scheduled work hours fell most heavily on workers in low-wage industries and on people of color, who face long-standing inequities often stemming from structural racism in education and employment.[42] Both groups were already more likely to struggle to afford housing. By January 2021, an estimated 15.1 million adults living in rental housing — more than 1 in 5 adult renters — were not caught up on rent. People who have struggled to pay rent during the crisis are disproportionately people of color, renters with low incomes, and renters who have lost income.

The federal response to housing needs during the crisis was delayed — with emergency rental assistance and emergency housing voucher investments not being made until late December 2020 — leading to unnecessary hardship for millions of people. Because the number of families with vouchers and other federal rental assistance is limited by available funding and because that funding does not automatically expand to meet growing needs, large numbers of households were left waiting for policymakers to enact emergency rental assistance programs. Local, state, and federal eviction moratoriums have prevented many — though not all — families from losing their homes, but most families still must pay their rent and accumulate debt if they cannot. Federal lawmakers provided some rental assistance funds in the March 2020 CARES Act, but they did not enact large-scale funding for emergency rental assistance until late December 2020 — more than nine months after severe job losses began — with additional amounts included in the March 2021 American Rescue Plan.

Homelessness assistance systems necessarily operate via a scarcity model that requires front-line workers and homelessness assistance providers to make excruciating decisions about who will get needed resources. These are literally life and death situations. The most sick or “vulnerable” often receive assistance first, but vulnerability is hard to measure and looks different for different populations. Is a young person who is being trafficked in exchange for a place to sleep more “vulnerable” than a woman with a serious mental illness living on the street or a family with young children living in their car? These are the decisions that front-line staff are faced with every day.

This approach, while currently necessary, can be extremely difficult for those who implement it and can lead to high levels of staff burnout and turnover in a system that needs stability and consistency to function well. It is also retraumatizing for the people who come to these systems for help, only to be told they are not sick or needy enough to be at the top of the list for housing and/or services. People wait for assistance in dangerous situations on the street or in congregate shelters. Upticks in unsheltered homelessness can increase tension with housed people in neighborhoods that include encampments. They also can increase interactions with police and fire departments that are costly and do not resolve people’s needs or the homelessness crisis overall.

Expanding the Housing Choice Voucher program can change this dynamic, not immediately but by providing the critical basis for significant change. Voucher expansion would increase access to housing as both a prevention strategy for households experiencing housing instability and a rehousing strategy for families, youth, and individuals who are in crisis or exiting systems like foster care, jails, or hospitals. For some, a voucher alone will enable them to obtain housing and maintain stability. Others will need safe and affordable housing coupled with supportive services such as case management, substance use treatment, mental or physical health services, or other types of community-based supports to maintain housing and live full lives.

Imagine a homelessness assistance system that, instead of being forced to prioritize people based on how sick or in danger they are, can quickly offer a family, youth, or individual in crisis a permanent housing option. A system that prioritizes working with landlords to create and maintain positive relationships that benefit people experiencing homelessness, the business community, and neighborhoods. A system that has a housing placement for a person who experienced unsheltered homelessness and chose to enter substance use treatment but needs housing to maintain their sobriety and housing stability. A system that provides outreach to people living on the street — outreach that actually includes a housing option rather than only a blanket, bottle of water, or granola bar.

We have much work to do to realize that vision. There are many partnerships to build and nurture. But the most important first step is to expand the Housing Choice Voucher program to all eligible households in the United States.