BEYOND THE NUMBERS

Rental Assistance Needed to Build a Recovery That Works for People With Disabilities

As Congress considers the Administration’s recovery proposals, lawmakers have a historic opportunity to address on a long-term basis homelessness and housing instability among people with disabilities by significantly expanding the Housing Choice Voucher program to more households. Ultimately, housing vouchers should be available to everyone who is eligible, as President Biden proposed during his presidential campaign. At a minimum, recovery legislation should make a sizeable down payment toward this goal.

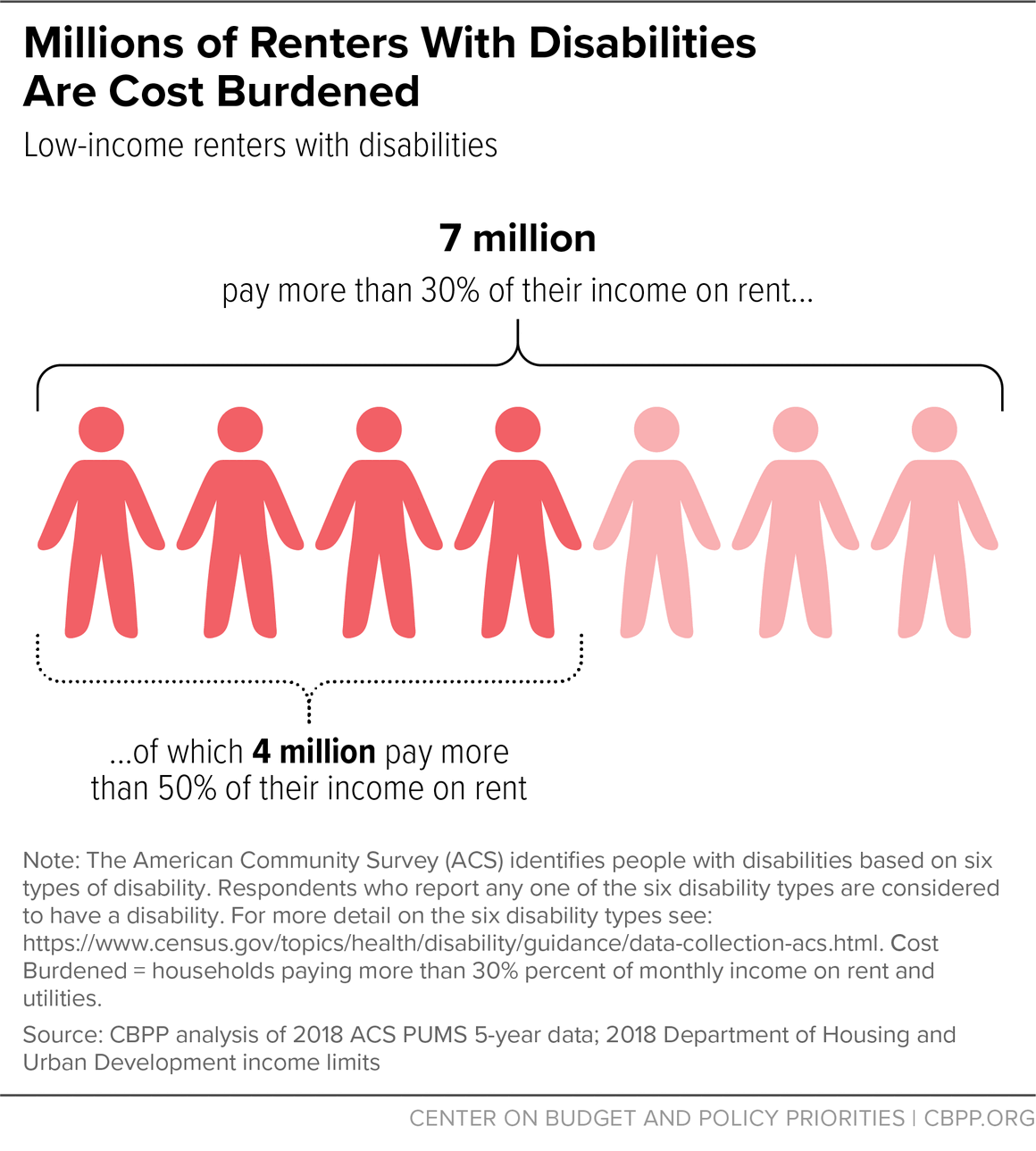

More than 4 million people with disabilities are in families that pay more than half their incomes in rent and utilities. (See figure.) At the same time, over 110,000 people with disabilities are experiencing chronic homelessness (long-term or repeated homelessness). All of that undermines access to health care for people with disabilities, and it forces people to live in congregate or institutional settings that undermine their independence and, in some cases, endanger their health.

Structural barriers to employment, education, and supportive services contribute to high poverty rates for people with disabilities and make it harder for many of them to afford housing. Systemic racism compounds these barriers for people of color. Over 4 million people with disabilities receive Supplemental Security Income (SSI), but its benefits are modest — the basic monthly SSI benefit in 2021 is $794 for an individual — and, in many places, they aren’t enough alone to cover rent even if people allocate every dollar of their benefits to pay rent. Many people with disabilities who qualify for SSI don’t receive benefits because they have not successfully completed the arduous application process. And many people with disabilities who struggle to afford rent don’t meet the strict medical or income eligibility criteria for SSI.

Expanding vouchers is essential to building an equitable recovery in which people with disabilities can live safely and pursue their goals. It would help millions of people with disabilities, including by:

- Reducing poverty. Providing vouchers to all eligible households would lift 1 million people with disabilities out of poverty, reducing poverty among people with disabilities by 25 percent — and by even more among Black and Latinx people with disabilities — according to Columbia University researchers.

- Helping to end homelessness. Expanding vouchers is key to increasing access to permanent supportive housing, an evidence-based solution to homelessness among people with disabilities that pairs rental assistance with case management services that help people find and keep housing.

- Providing more people with the choice to live in the community instead of nursing homes, psychiatric facilities, and other congregate care facilities. That also would help states meet their obligation under the Supreme Court’s Olmstead v. L.C. decision to serve people with disabilities in the community rather than institutions when community-based services can meet their needs.

- Making the community more inclusive of people with disabilities by helping more of them live in the neighborhood that best meets their needs — such as near grocery stories, schools, health care services, or social supports that facilitate community living. Vouchers may be particularly important for people of color with disabilities, who often have even more limited housing choices due to the long history of discriminatory policies that created and still reinforce racial segregation.

The President’s American Jobs Plan would expand the stock of less expensive housing, which is important to address housing supply issues in coastal cities and create more accessible housing for people with limited mobility, vision, or hearing. Supply-side investments alone, however, can’t create enough housing that’s affordable for people with incomes near the poverty line, including millions of seniors and people with disabilities. Rents are still out of reach for people with extremely low incomes in the large parts of the country where housing supply is adequate. Vouchers are much more cost effective than new construction in these areas. And capital subsidies to renovate or build housing alone generally do not produce housing with rents that are affordable to the lowest-income renters because the ongoing costs of maintaining the building far exceed the rents low-income families can afford.

More vouchers also will be crucial to ensure that people with poverty-level incomes can fully benefit from the $400 billion proposal in the American Jobs Plan to expand Medicaid home- and community-based services (HCBS) for people who would otherwise need to get care in a nursing home or other institutional setting. Expanding HCBS would help more people live safely in their homes and communities rather than in congregate settings, which account for nearly one-third of all COVID-19 deaths, according to the latest available data.

Since many seniors and people with disabilities (such as those who rely mainly or entirely on SSI) don’t have enough income to afford rent, however, some may be compelled to remain in institutional settings and unable to use the expanded services. Others could be forced to pay such high shares of their income for rent that they will be at risk of hardship — such as eviction, food insecurity, and utility shutoffs — that could jeopardize their health and access to HCBS. For these seniors and people with disabilities, more vouchers would prove particularly consequential for accessing HCBS.