Low-income mandatory programs — programs funded outside the annual appropriations process that help struggling families pay rent, put food on the table, and access health care — are not driving the nation’s long-term fiscal problem. That is, they are not the reason that the debt is projected to rise faster than the economy in future decades.[1] Spending on low-income health programs is projected to grow as a percent of the economy over the coming decade, but this increase will be almost entirely offset by the decline in other low-income mandatory programs. Overall, spending on these programs — health and non-health combined — is expected to tick up only slightly, from 3.7 percent of the economy in 2019 to 3.8 percent in 2029.

Despite this, President Trump and some policymakers often call for deep cuts to these programs. The first two Trump budgets, for example, included deep cuts that would have increased poverty and the number of Americans without health insurance.[2]

Mandatory Programs Outside Health Care Shrinking as Share of Economy

Mandatory programs for low- and moderate-income people provide basic assistance to struggling families. They include health care programs such as Medicaid, the Children’s Health Insurance Program, and the premium subsidies in the Affordable Care Act. They also include programs outside health, such as SNAP (formerly food stamps), the refundable portions of the Earned Income Tax Credit and the Child Tax Credit, Supplemental Security Income (which provides income assistance to poor seniors and poor people with disabilities), and Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF). Low-income mandatory programs keep millions of families out of poverty, reduce the depth of poverty for millions more, help tens of millions of people obtain health insurance, and improve the nutrition of families in need.

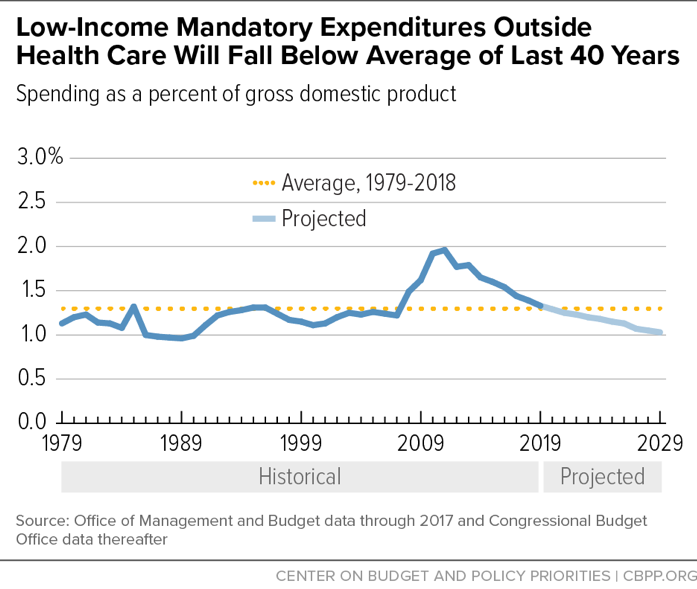

Total spending for mandatory low-income programs outside health care is only modestly above its average over the past 40 years (1979-2018), measured as a share of gross domestic product (GDP). In recent years, the cost of these programs has shrunk significantly, in large part due to the economy’s recovery from the Great Recession. And spending on these programs is projected to fall below the past 40-year average, as a share of GDP (see Figure 1).

To be sure, spending on Medicaid and other low-income mandatory health programs is above its 40-year average as a percent of GDP. This is due both to rising health care costs systemwide, in both the public and private sectors, and to policymakers expanding Medicaid, creating the Children’s Health Insurance Program, and establishing subsidies so low- and moderate-income households can afford private coverage. These policy changes expanded access to health coverage for millions of Americans.

The cost of low-income health programs is projected to continue rising as a percent of GDP.[3] This is chiefly due to the aging of the population, which has made more seniors (who have higher health care costs) eligible for Medicaid, and to the longstanding rise in costs throughout the U.S. health care system, which partly reflects medical advances that improve health and save lives but also add to costs. Medicaid continues to cost far less per beneficiary than private health insurance, and its costs are rising more slowly, making Medicaid the health insurance system’s most economical and efficient part.

Spending on low-income health programs is estimated to grow from 2.4 percent of GDP in 2019 to 2.8 percent in 2029. But this will mostly be offset by the decline in other low-income mandatory programs. As a result, the total cost of low-income mandatory programs, including health programs, is projected to edge up only slightly over the coming decade, from 3.7 percent of GDP to 3.8 percent (see Table 1).

| TABLE 1 |

|

|---|

| Spending on Low-Income Mandatory Programs, Percent of GDP |

|---|

| |

1979-2018 average |

2010 |

2019 |

2029 |

|---|

| Low-income mandatory programs, excluding health |

1.3 |

1.9 |

1.3 |

1.0 |

| Low-income mandatory health programs |

1.3 |

2.1 |

2.4 |

2.8 |

| Total, low-income mandatory programs |

2.6 |

4.0 |

3.7 |

3.8 |

Critics often cite spending growth in low-income mandatory programs over the past decade to justify large cuts, but the decade really consists of two very different periods. Mandatory spending for low-income programs outside health care rose from 1.2 percent of GDP in 2007 to 2.0 percent of GDP in 2011. This reflected increased need during the Great Recession and temporary policies adopted in response. It also reflected expansions of the Earned Income Tax Credit and Child Tax Credit to help low-wage workers better provide for their families.

But as the economy improved, mandatory spending for low-income programs outside heath care dropped significantly and is expected to equal 1.3 percent of GDP in fiscal year 2019. (It’s fallen in inflation-adjusted terms as well since 2011.) As one illustration of this pattern, the number of SNAP participants has fallen by about 9 million, or about 20 percent, since peaking in December 2012.[4]

Spending on Medicaid and other low-income health care programs also followed this pattern through 2014: rising during the Great Recession, then starting to fall. This spending then rose in 2015 as the Affordable Care Act provided health coverage to millions of households, producing historic progress in reducing the number of uninsured.

Lower unemployment and higher household earnings have significantly reduced the number of people in poverty in recent years,[5] but many working families continue to struggle with low earnings, as President Trump himself has pointed out. Many families continue to need assistance to afford the basics.

Recent and future trends in spending on mandatory programs aren’t a justification for cuts in the low-income assistance programs, especially when Republican lawmakers in 2017 enacted costly tax changes that primarily benefit the wealthy and corporations and do relatively little for low- and moderate-income people.[6] Ultimately, addressing our nation’s longer-term fiscal challenges will require a broader approach that recognizes the need for additional revenues.[7]