The Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) provisions in House Speaker Kevin McCarthy’s debt-limit-and-cuts bill double down on TANF’s already expansive, rigid, and ineffective work requirements. The bill would so severely limit states’ flexibility in how they provide assistance and employment services to families with children that some states could decide to stop providing cash aid to large numbers of families, with devastating results.

The bill would make existing work requirements in TANF more stringent by effectively raising the share of parents receiving TANF whom states are required to have participate in a narrow and rigid set of federally approved work activities for a certain number of hours each month. This would be done through technical changes to the complex TANF work participation requirements that would eliminate or significantly restrict the strategies states have used both to provide cash assistance to families for whom the rigid federal requirements are not well suited and to construct more effective, tailored employment strategies for parents.

In 2021, about 540,000 “work-eligible” families with children (families subject to the work requirements) received TANF cash assistance; those families included some 975,000 children.[1] This group is at risk of losing cash assistance if states determine that they can’t meet the McCarthy bill’s more rigid requirements and, as a result, restrict access to assistance rather than risk federal financial penalties.

Program administrators across the political spectrum agree that TANF’s already narrow and rigid work requirements fail to address the needs of families who turn to TANF for support. In a recent House Ways and Means Committee hearing,[2] a program administrator from North Carolina, invited by the Republican members, expressed the following concern about the TANF work requirements:

Focusing on the [work] rate as the only means of measurement for success within the workforce program removes the human aspect of the program. Participants in the program are often overcoming immense obstacles, such as trauma, homelessness, mental and physical health concerns, [and] substance use issues, and yet are required to fully participate in the program.

Research supports these sentiments. TANF’s work requirements do not lift families out of poverty and they leave families with the most significant needs without any cash assistance to meet their basic needs.[3]

When families don’t have access to cash assistance to pay their rent and utilities, to purchase personal hygiene and household cleaning supplies, and to buy diapers and clothing for their children, hardship increases with dire results, including increased involvement in the child welfare system,[4] homelessness, higher incidences of mental health issues, and costly health problems.[5]

These negative outcomes extract a significant toll on children. Children can experience toxic stress: chronic, high levels of stress that over time significantly impact physical and mental health. Children who experience significant adversity are at increased risk of life-altering conditions, including heart disease, diabetes, depression, arthritis, gastrointestinal disorders, autoimmune diseases, multiple types of cancer, and dementia, as well as an increased risk of untimely death.[6] In addition to the harm this causes children and their parents, the long-term costs to government are significant as these issues are all more costly to address than providing families with cash assistance to meet their basic needs.

Despite their reservations about the rigid federal requirements, most states focus their programs on engaging recipients in work activities as defined by federal law. This means that states take assistance away from many families who can’t meet work requirements, including those for whom the federally specified work activities are not appropriate or the best strategy for improving their circumstances.

To avoid taking benefits away from families who are unable to meet rigid federal requirements, some states use available flexibilities to provide assistance that is more consistent with families’ needs, for example, helping families fleeing domestic violence to find housing, address trauma, and rebuild their lives. While the details are complicated, the McCarthy bill essentially seeks to undo those flexibilities. That would make it far more difficult, and perhaps impossible, for states both to provide cash assistance to families who need it most and to meet the federal requirements.

When TANF was reauthorized through the Deficit Reduction Act of 2005, provisions that limit state flexibility in ways less severe than those proposed by Speaker McCarthy resulted in a precipitous decline in the TANF caseload; between 2005 and 2008, the caseload fell by 18.5 percent.[7] States might have restricted access to assistance even further if they could not use the flexibilities that remained in the law. If states reacted to the McCarthy bill’s limitations by cutting caseloads by 18.5 percent, some 100,000 families with 180,000 children would no longer have access to cash assistance to meet their basic needs.

The TANF provisions in the McCarthy bill would also likely exacerbate racial disparities. Nearly every study comparing the race and ethnicity of TANF participants who had benefits taken away for not demonstrating compliance with a work requirement with those who did not lose benefits finds that Black participants are significantly more likely to have their benefits taken away than white participants, with caseworker bias a significant factor.

The current TANF law has a complicated set of requirements that mean that states must have a specified share of “work-eligible” individuals engaged in a narrow set of activities for a federally specified number of hours each week, regardless of whether those activities or hourly requirements are appropriate or even reasonable given someone’s circumstances.[8]

TANF rules define a work-eligible individual as an adult (or minor head of household) receiving assistance or a parent living with a child receiving assistance even if the parent is not. The rules exclude from this definition some parents who are not receiving TANF assistance: disabled recipients receiving cash payments from Supplemental Security Income or Social Security Disability Insurance, parents ineligible due to their immigrant status, and a parent providing care for a disabled family member that requires the parent to remain in the home. In addition, states have the option to exclude parents in single-parent families that contain a child under age 1 for 12 months once in a lifetime; families receiving assistance under a tribal family assistance plan or work program; and families under sanction for failure to meet work requirements (for no more than three months in a 12-month period).

Someone who is ill or caring for a sick family member, has recently been evicted and needs to find housing, or is contending with a substance use disorder may need different types of services to stabilize their families. Because those activities are not included in the list of federal activities, they do not help a state to meet their federal work participation requirement.

Currently, states use flexibilities in the law to provide assistance to families with significant needs who are unable to work or participate in work activities for the required number of hours, at least for some period of time. The TANF provisions in the McCarthy bill would take that flexibility away, leaving states with few options for serving families with the greatest needs.

Understanding TANF’s Current Work Requirements and Flexibilities

Several key features of TANF work requirements are important for understanding the harmful impacts of the McCarthy bill.

First, the 1996 federal law that created TANF requires states to engage TANF recipients in “work,” with the definition left to the state.

But the law also requires states to meet a work participation rate (WPR) that creates incentives for states to restrict access to the program to individuals who can meet the narrowly defined work requirements or to develop alternative strategies for meeting the work rate that allow more families in need to access the program. The McCarthy proposal threatens these alternative strategies, as we explain below.

States are required to meet two different work participation rates, 50 percent for all families and 90 percent for two-parent families. To be counted in the WPR, families must participate in a narrow, federally defined set of work activities for 30 hours per week (or 20 hours for families with a child under the age of 6). The WPR a state must achieve is reduced by 1 percentage point for every percentage point decline in their TANF caseload since 2005. This “caseload reduction credit” is intended to reward states for moving recipients from the caseload into work, but they receive credit even if the recipient is not employed when they leave TANF.

Because TANF caseloads have declined significantly since 2005 — 53 percent nationally — most states have a WPR “target rate” that is substantially lower than the 50 percent rate for all families and the 90 percent rate for two-parent families. States can also earn additional caseload reduction credits if they spend more state funds than required to meet their state funding obligation, known as state maintenance of effort (MOE).

Although many states have work participation target rates below the 50 or 90 percent rate, federal law still requires them to engage recipients in work activities (the flexible requirement described above) and to take benefits away from those who do not document compliance with the requirement.

States can exempt work-eligible recipients with significant employment barriers from meeting the work requirement or place recipients in activities that do not meet the federally defined requirements for the type of activity or the number of hours, but these families are still counted in the denominator of the calculation of the work participation rate.

That means, in a scenario where a state must meet the 50 percent WPR for all families, if it serves 100 recipients who are exempt from rigid federal work requirements, it must serve another 100 who meet the narrow work participation rate requirements. If just one of the 100 who are not exempt fails to participate in work activities that are defined as counting toward the rate for sufficient hours, the state will fail to meet the WPR and could face reductions in its block grant that it must then replace with additional state spending.

Recognizing that rigid requirements don’t serve states or families well, the American Public Human Services Association, working with TANF administrators and human services leaders across the country to reimagine TANF, called on policymakers to replace the restrictive and complicated TANF work requirements with activities — jointly identified with participants — to support family well-being and economic mobility.[9] But the McCarthy bill goes in the opposite direction, making the TANF requirements states must meet more rigid.[10]

The bill’s TANF provisions would take flexibilities away, making it far more difficult for states to meet the work participation rate requirements. That could push states to choose not to provide cash assistance to families with high needs who are least likely to be able to meet the rigid work participation rate standards.

The bill would restrict flexibility through the following changes:

Recalibration of the caseload reduction credit, which would reset the credit close to zero for every state, nearly eliminating it as a strategy for meeting the WPR. States would be required to meet the 50 percent WPR for all families and 90 percent for two-parent families. The comparison year for calculating the credit would be changed from 2005 to 2022. With TANF caseloads at their lowest level ever, any caseload reduction would come at the expense of families with the most significant needs who cannot demonstrate from the outset that they can meet the rigid work requirements.

This provision is likely to eliminate access to TANF for all two-parent families because the 90 percent rate for two-parent families has proven to be especially hard to meet; due to this requirement 24 states and the District of Columbia and Puerto Rico already no longer serve two-parent families in their TANF programs. Because few two-parents families receive cash assistance, some states have chosen to provide cash assistance to these families using state funds (beyond those they are required to spend to receive their federal TANF funds).

- Elimination of the “excess maintenance of effort” provision that translates state spending that exceeds the amount required by federal law into additional caseload reduction credits. This provision rewards states for spending additional state funds to meet one of TANF's four purposes.[11] Under the existing maintenance of effort provision, all states must spend 80 percent of the amount of state funds they spent on four categories of spending in programs in place before TANF was created (cash grants, child care, employment assistance, and emergency assistance) in 1994. The amount is reduced to 75 percent if a state meets its target work participation rates. Anything a state spends above the required amount is translated into caseload reduction credits through a formula.

Imposition of additional requirements on families receiving small cash payments. Some states provide small cash payments to support working families (usually former TANF recipients or current SNAP recipients). Because these families are working and the benefits are paid with state TANF funds, states can count them as meeting the TANF work requirement, without subjecting them to other requirements that TANF recipients face (such as the five-year time limit on receiving assistance).

The legislation would allow states to count such families as meeting the work requirements only if the families: (1) agree to cooperate with child support enforcement; (2) assign any child support received to the state; and (3) undergo an evaluation to assess their skills, prior work experience, and employability. The costs that states would incur to implement these requirements and the additional burden they would place on recipients would likely lead states to eliminate these small payments.

The sharp restriction in flexibilities would leave states with limited options to meet the work participation rate: (1) restrict access to families where the parent(s) is able to demonstrate they can meet the onerous work participation requirement before their application for assistance is approved — and then assign them to activities and hourly requirements that meet the federal work rate strictures; or (2) assign parents to the narrowly prescribed activities for the required number of house and take benefits away from the whole family more quickly when parents are unable to meet the work requirements, even if they weren’t reasonable given the families’ circumstances. Both strategies would result in families in need being denied assistance to help them meet their basic needs.

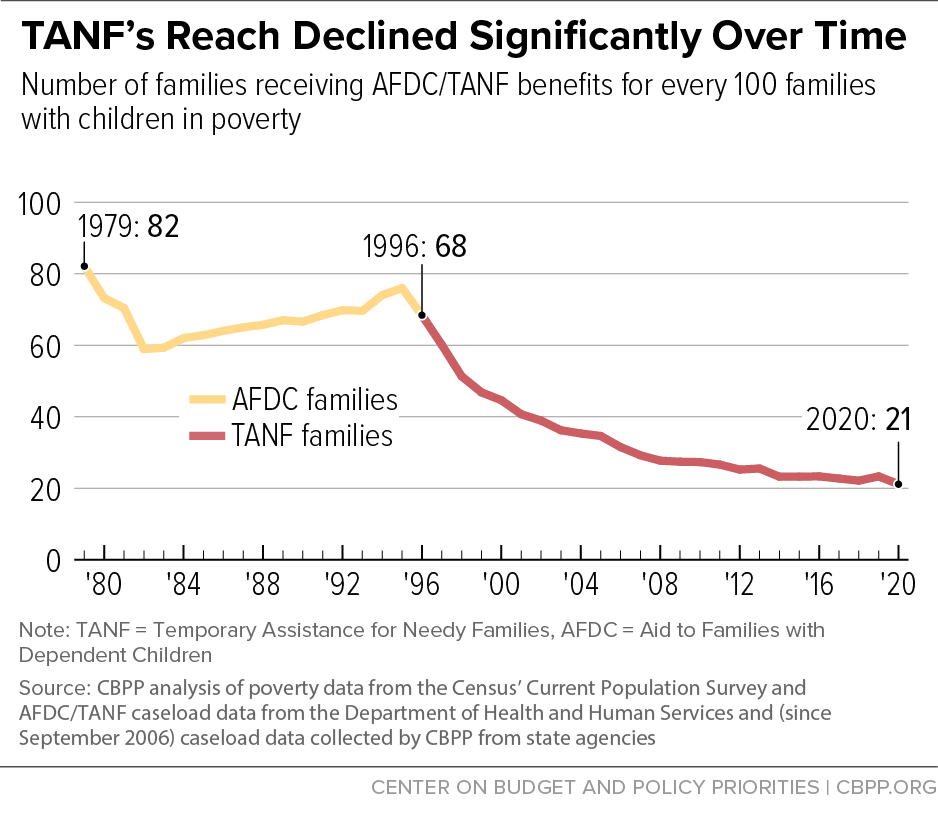

TANF already serves only a fraction of families who need cash assistance to meet their basic needs. In an average month in fiscal year 2020, only about 1 million families received TANF cash assistance, down from 4.4 million families in an average month in fiscal year 1996, the year before the current rigid and narrowly defined work requirements were implemented. And for every 100 families in poverty nationwide, only 21 received TANF cash assistance in 2020 — down from 68 families in 1996.[12] (See Figure 1.)

In 2021, 540,000 families — 56 percent of the 960,000 families receiving cash benefits in an average month — included a work-eligible adult, meaning that they are subject to work requirements. These families include 975,000 children. (The 44 percent of families not subject to work requirements are “child-only” cases where the parent is not in the household or is excluded from the grant for a reason other than not meeting a work requirement.) (See Table 1 for the number of families with a work-eligible adult and the number of children in those families in each state, the District of Columbia, and the territories.)

The McCarthy proposal would put all 540,000 work-eligible families at risk of losing their access to cash benefits. Some would be at risk because they receive small-dollar payments that states would likely eliminate. Others would be at risk because they cannot participate for the required hours or in the activities that would let a state count them as meeting the work rate. Still others will be at risk because states, facing unworkable federal requirements, could simply make it far harder to apply for TANF in the first place.

Some families who could lose TANF may be pursuing education that will improve their employment opportunities and earnings, but in programs that don’t count toward the work participation rate. For example, students whose college coursework would not count toward the work requirement could be faced with losing TANF or dropping out of school. Currently, states use the flexibility that the McCarthy bill would take away to allow recipients to complete college even though their participation does not count toward meeting the work participation rate.

The TANF provisions in the McCarthy bill would also likely exacerbate racial disparities. Nearly every study comparing the race and ethnicity of TANF participants who had benefits taken away for not demonstrating compliance with a work requirement with those who did not lose benefits finds that Black participants are significantly more likely to have their benefits taken away than white participants.[13] Researchers using fictitious case examples to examine racial bias found that caseworkers were much more likely to sanction Black mothers who had previous sanctions than they were to sanction white women with previous sanctions; the case examples varied only by the mother’s race.[14]

A lack of cash assistance, or increased barriers to access it, also increases the likelihood that families will become involved with the child welfare system, where Black and brown families are over-represented due to historical and systemic racism that continues to bring an excessively harsh lens of assessment and examination during interactions with these families. One study that estimated the impact of policy changes between 2004 and 2015 found that substantiated child neglect reports increased by 23.3 percent in states that implemented the most severe sanction for not meeting a work requirements; foster care entries due to child neglect increased by 13.4 percent and total foster care entries increased by 12.7 percent.[15]

Proponents of work requirements often claim that they offer families a path out of poverty. However, the evidence from an array of rigorous evaluations does not support the view that work requirements are highly effective.[16] Instead, the research shows that:

- Employment increases among recipients subject to work requirements were modest and faded over time.

- Stable employment among recipients subject to work requirements proved the exception, not the norm.

- Most recipients with significant barriers to employment never found work even after participating in work programs that were otherwise deemed successful.

- The large majority of individuals subject to work requirements remained poor, and some became poorer.

| TABLE 1 |

|---|

|

| | Number of families subject to work requirements at risk of losing benefits | Number of children at risk of losing benefits |

|---|

| Alabama | 2,278 | 4,328 |

| Alaska | 1,176 | 2117 |

| Arizona | 2,193 | 3,728 |

| Arkansas | 805 | 1369 |

| California | 193,795 | 387,590 |

| Colorado | 6,736 | 12,125 |

| Connecticut | 2,461 | 3,445 |

| Delaware | 513 | 821 |

| District of Columbia | 4,584 | 10,543 |

| Florida | 9,879 | 13,831 |

| Georgia | 1,412 | 2,400 |

| Guam | 165 | 314 |

| Hawai’i | 5,155 | 10,310 |

| Idaho | 30 | 42 |

| Illinois | 2,244 | 4,039 |

| Indiana | 4,615 | 8,307 |

| Iowa | 3,804 | 6,847 |

| Kansas | 1,630 | 2,771 |

| Kentucky | 3,149 | 5,038 |

| Louisiana | 1,121 | 2,130 |

| Maine | 10,184 | 17,313 |

| Maryland | 17,176 | 29,199 |

| Massachusetts | 30,603 | 48,965 |

| Michigan | 3,666 | 6,965 |

| Minnesota | 12,358 | 22,244 |

| Mississippi | 247 | 395 |

| Missouri | 4,443 | 7,997 |

| Montana | 866 | 1,559 |

| Nebraska | 1,479 | 2,958 |

| Nevada | 2,931 | 5,569 |

| New Hampshire | 2,321 | 3,714 |

| New Jersey | 5,739 | 10,330 |

| New Mexico | 7,223 | 13,001 |

| New York | 72,496 | 115,994 |

| North Carolina | 4,287 | 6,431 |

| North Dakota | 610 | 1281 |

| Ohio | 7,439 | 11,902 |

| Oklahoma | 1,620 | 3,726 |

| Oregon | 25,664 | 43,629 |

| Pennsylvania | 15,519 | 27,934 |

| Puerto Rico | 4,011 | 6819 |

| Rhode Island | 1,524 | 2743 |

| South Carolina | 2,668 | 5,069 |

| South Dakota | 359 | 646 |

| Tennessee | 4,694 | 7,980 |

| Texas | 6,318 | 10,741 |

| Utah | 972 | 1,652 |

| Vermont | 844 | 1,266 |

| Virgin Islands | 59 | 136 |

| Virginia | 8,174 | 13,896 |

| Washington | 28,884 | 46,214 |

| West Virginia | 1,352 | 2,163 |

| Wisconsin | 6,277 | 11,299 |

| Wyoming | 241 | 434 |

| United States | 540,993 | 973,787 |