Cash assistance to families with low incomes is critical both to help them stabilize their circumstances and to create conditions in which they can thrive. A new body of research compiled by Chapin Hall, a research and policy center that focuses on child welfare and family well-being at the University of Chicago, finds that material hardship increases the risk for child welfare involvement due to neglect and abuse, and when families are given cash assistance, their risk for child welfare involvement is reduced.[2]

The message from Chapin Hall’s compilation of research is clear: income supports to families with low incomes, like those provided through the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) program, reduce risk for child maltreatment and the child welfare system involvement that results from it.[3] Understanding this link is critical to reversing the negative impacts of the racist histories of both TANF[4] and the child welfare system, and to seizing the opportunity to improve outcomes. This is especially important as families of color continue to experience disproportionate harm at the intersection of TANF and the child welfare system.

States can use TANF funds on a broad array of purposes. But given the strong link between cash assistance and child well-being, TANF can and should be structured to ensure that its funds are used to provide more cash assistance to more families struggling to meet their basic needs.[5]

Parents with low incomes are often caught at the crossroads of deciding between spending time with their children or working long hours at low-paying or informal jobs just to make ends meet. Providing cash to families with low incomes enables parents to meet their children’s basic needs and invest in their children’s future. This is especially relevant for families of color, many of whom have faced past and present discrimination in employment, access to quality education, and access to economic security programs.[6]

Meeting children’s material needs, including nutritious food and regular medical care, supports their healthy development. Poverty is not supposed to be a cause for reporting child welfare cases, but when children lack food, are often sick, or repeatedly act out (which may be due to hunger, lack of sleep due to homelessness, etc.), it can attract the attention of child welfare agencies. Giving families cash assistance reduces these problems.

For example, a CBPP study that examined the possible effects of cash delivered as part of a permanently expanded Child Tax Credit found that it would reduce the number of children living in poverty by 4.1 million.[7] Multiple studies have found that expanding the credit would narrow the racial and ethnic disparities in poverty rates, helping especially large shares of Black, Latinx, and/or American Indian and Alaska Native children, whose risk of poverty is well above the national average.[8]

The CBPP analysis found that a permanent Child Tax Credit expansion would benefit nearly 9.4 million Black children and narrow the difference in the poverty rates between Black and white children by 44 percent. It would benefit nearly 17.6 million Latinx children and narrow the difference in the poverty rates between Latinx and white children by 41 percent. It would also reduce the poverty rate for American Indian and Alaska Native children from 18 percent to 10 percent, and for Asian children from 13 percent to 9 percent.[9]

There are additional long-term, positive outcomes for children in families with low incomes who receive cash assistance.[10] In addition to reducing childhood poverty, cash payments decrease the likelihood of young adult poverty, which young Black adults experience at particularly high rates due to factors related to systemic racism.[11] Cash assistance also supports children’s well-being and healthy development and improves children’s long-term academic, economic, and health outcomes, according to a report by the National Academies of Sciences on reducing childhood poverty.[12] And giving cash to families who are struggling also helps reduce parents’ financial stress, giving them more time and energy to focus on their children’s well-being and development.[13]

Chapin Hall’s analysis, which compiled studies that examine the intersection of public cash assistance programs and child welfare involvement due to reports of maltreatment, shows that state policies that ease TANF restrictions and increase family access to TANF, such as providing more cash, increasing eligibility to receive child support, and lessening the severity of sanctions for not meeting work requirements, play a role in reducing child welfare involvement.[14]

For instance, one study examined the association between states’ changing TANF policies and child maltreatment between 2004 and 2015. It found that each additional $100 monthly in a state’s TANF cash benefit level is linked to 1.8 fewer occasions of mothers reporting physically maltreating their child.[15]

Another study found improvements in children’s well-being as several states eased certain restrictions on TANF from 2004 to 2016. The researchers estimated that if all states had expanded TANF access in these ways, fewer children would have experienced substantiated neglect and an estimated 29,112 fewer children would have entered foster care nationally. The TANF restrictions included time limits of less than 60 months, severe sanctions for not meeting work requirements, work requirements for mothers with children less than 12 months of age, and suspicion-based drug testing of applicants.[16]

Further, several studies explore the positive impacts of certain TANF-related policies, such as child support eligibility. One study found that mothers who participate in TANF and are eligible to receive full child support (rather than having their child support withheld by the state) are 10 percent less likely to have their child be the subject of a maltreatment report that finds cause for further investigation (known as a “screened-in” report), compared to mothers who are eligible to receive only partial child support payments.

Some of the studies Chapin Hall reviewed focused on the impact that a lack of assistance or increased barriers to access has on families. Those studies found that families who didn’t have access to assistance (but had very low incomes) were more likely to be involved with the child welfare system.

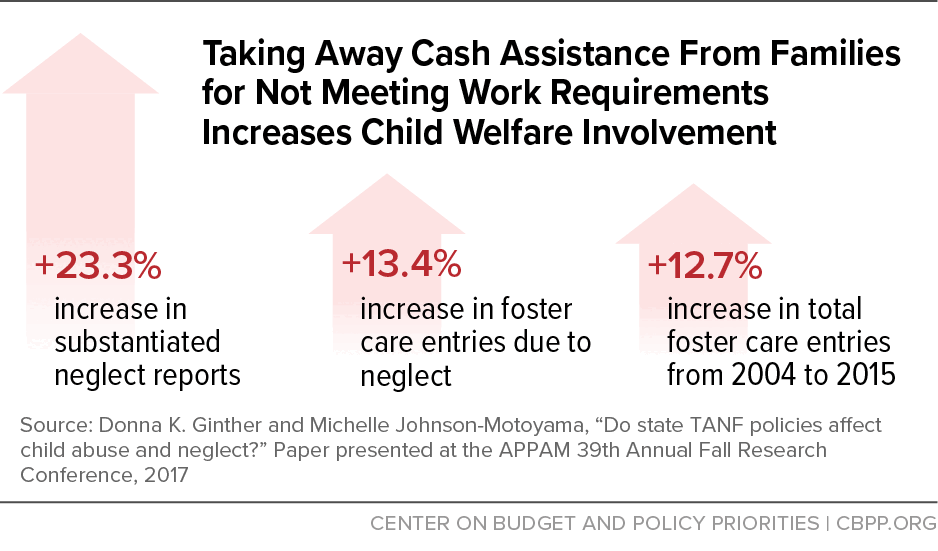

One of the barriers that families face are policies that take cash assistance away for not meeting a work requirement.[17] One study that estimated the impact of policy changes between 2004 and 2015 found that substantiated child neglect reports increased by 23.3 percent in states that implemented the most severe sanction of taking all of a family’s benefits away for the parent not meeting a work requirement; foster care entries due to child neglect increased by 13.4 percent and total foster care entries increased by 12.7 percent. (See Figure 1.)

Additionally, in states with TANF time limits of less than five years, the same study found there was about a 34 percent increase in substantiated maltreatment reports and about a 37 percent increase in substantiated neglect reports after the policy was implemented.

One study cited by Chapin Hall shows that if families with low incomes experience at least one type of material hardship, there is a three times higher likelihood than a similar family of a neglect investigation and a four times increased likelihood of a physical abuse investigation.[18]

It is clear that when families have more limited access to economic and concrete supports, like TANF, they are more likely to have involvement with the child welfare system.

Families strive to meet their children’s basic needs. Providing cash to families can help lessen racial inequities, reduce the risk of economic hardship by promoting stability, and thus reduce child maltreatment and family involvement in child welfare.

This is a compilation of all TANF-related studies cited in Chapin Hall’s slide deck.[19]

Slide 18: Yang (2015) found that if families with low incomes experience at least one type of material hardship, there is about a three times higher likelihood of neglect investigation and about a four times higher likelihood of a physical abuse investigation. Additionally, if families with low incomes experience multiple types of material hardship (after experiencing no hardships), there is about a four times higher likelihood of a Child Protective Services (CPS) investigation and about a seven times higher likelihood physical abuse investigation.

Slide 22: Cancian et al. (2013) found that mothers who participate in TANF and are eligible to receive full child support for their children (and child support is disregarded in determining welfare benefits) are 10 percent less likely to have a child subject to a maltreatment report that finds cause for further investigation (known as a “screened-in” report) compared to mothers who are eligible to receive only partial child support payments). Even a modest increase in child support payments — averaging $100 per year — results in a decrease in screened-in maltreatment reports.

Slide 50: Ginther and Johnson-Motoyama (2017) found that states that imposed total benefit loss as the most severe sanction for not meeting TANF work requirements, after implementation of the policy, saw a 23.3 percent increase in substantiated neglect reports, a 13.4 percent increase in foster care entries due to neglect, and a 12.7 percent increase in total foster care entries between 2004 and 2015.

Slide 53: Ginther and Johnson-Motoyama (2017) found that states that implemented TANF time limits of less than five years saw a 34.4 percent increase in substantiated maltreatment reports and a 37.3 percent increase in substantiated neglect reports.

Slide 55: Ginther and Johnson-Motoyama (2022) found that each additional state policy that restricts access to TANF is associated with 50 additional children with substantiated neglect reports, 22 additional children entering foster care due to abuse, and 21 additional children entering foster care due to neglect per 100,000 children between 2004 and 2016.

Slide 56: Spencer et al. (2021) found that state policies that limit access to TANF benefits, such as reducing the maximum allowable cash benefit amount, implementing stricter time limits on receipt of benefits, and a lower share of families with incomes below the poverty line receiving TANF (the TANF-to-Poverty Ratio), are associated with increases in mothers’ self-reports of physical child maltreatment (from 2001 to 2010).

Slide 57: Swann and Sylvester (2006) found that from 1985 to 2000, reductions in Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC)/TANF cash benefit levels were a main predictor of the dramatic growth in state-level foster care caseloads during this period, and a 10 percent reduction in the average monthly AFDC/TANF cash benefit amount for a family of three was associated with a 2.3 percent increase in the foster care caseload rate.

Slide 104: Paxson and Waldfogel (2003) found that a 10 percent increase in state public benefit levels (AFDC/TANF and the value of food stamps) for a family of four is predicted to reduce foster care placements by 8 percent.

Slide 106: Ginther and Johnson-Motoyama (2022) found that an estimated 29,112 fewer children would have entered foster care nationally from 2004 to 2016 if states had eased TANF restrictions to increase access for families.

Slide 107: A study by Spencer et al. (2021) found that state policies that increase access to TANF are associated with reductions in maternal self-reported physical child maltreatment; a $100 increase in TANF cash benefits is associated with reductions in maternal self-reported physical child maltreatment.

Slide 112: Johnson-Motoyama et al. (2022) found that from 2004 and 2026, every 5 percent increase in the number of families receiving SNAP benefits was associated with an 8 to 14 percent reduction in CPS and foster care caseloads; implementation of multiple more generous SNAP policies was associated with larger reductions in child welfare involvement; and estimated reductions in CPS reports and substantiations were particularly large among states offering transitional SNAP benefits to families leaving TANF.

Slide 165: The report by American Academy of Pediatrics (2021), “Child Welfare: Recommendations for Public Policy Change,” expands on the scope of services eligible for federal reimbursement to include time-limited cash assistance to help families with low incomes meet concrete needs and minimize poverty-related neglect cases, as well as services that address behavioral health, housing instability, and domestic violence.