New Research Reinforces Case for Restoring Lost Housing Vouchers

End Notes

[1] The other interventions were transitional housing and short-term rapid rehousing assistance. A fourth group received no additional assistance via the study.

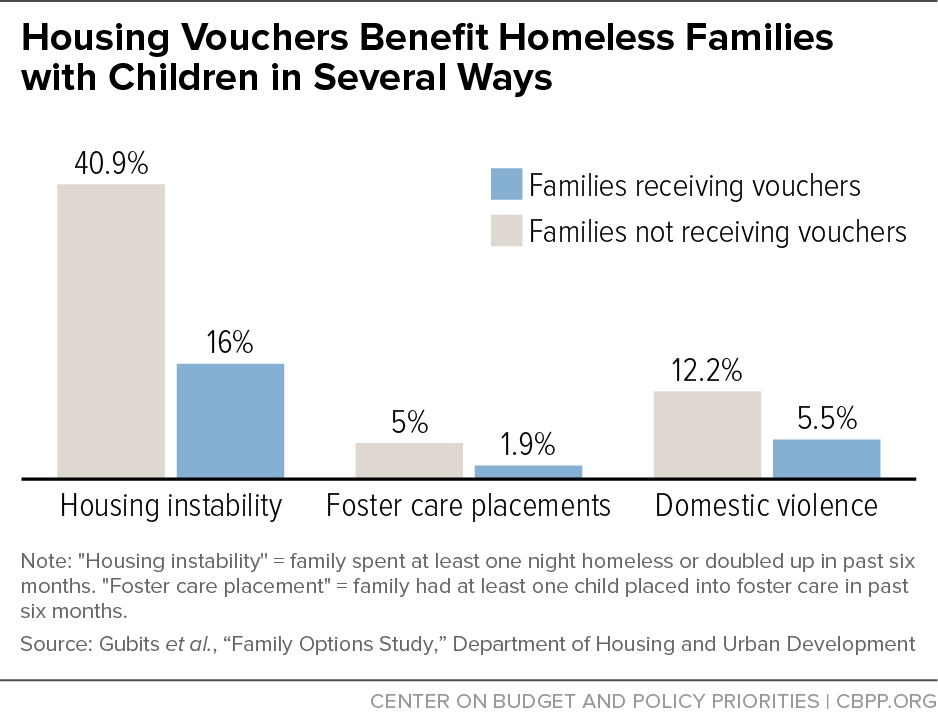

[2] Daniel Gubits et al., Family Options Study: Short-Term Impacts of Housing and Services Interventions for Homeless Families, prepared for Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), July 2015, http://www.huduser.org/portal/sites/default/files/pdf/FamilyOptionsStudy_final.pdf. For more on this and other research on the effectiveness of vouchers, see Will Fischer, “Research Shows Housing Vouchers Reduce Hardship and Provide Platform for Long-Term Gains Among Children,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, October 7, 2015, https://www.cbpp.org/research/housing/research-shows-housing-vouchers-reduce-hardship-and-provide-platform-for-long-term.

[3] The total average 20-month cost of assisting families receiving housing vouchers was about the same as for the homeless families who received no additional assistance under the study (because the latter tended to remain in costly shelter facilities for longer durations), slightly higher than for families receiving rapid rehousing assistance, and somewhat lower than for families in transitional housing.

[4] Michelle Wood, Jennifer Turnham, and Gregory Mills, “Housing Affordability and Family Well-Being: Results from the Housing Voucher Evaluation,” Housing Policy Debate, Vol. 19, issue 2 (2008), pp. 367-412; Gregory Mills et al., “Effects of Housing Vouchers on Welfare Families,” prepared for HUD Office of Policy Development and Research, September 2006.

[5] For more on sequestration, see David Reich, “Sequestration and Its Impact on Non-Defense Appropriations,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, February 19, 2015, https://www.cbpp.org/research/federal-budget/sequestration-and-its-impact-on-non-defense-appropriations.

[6] Alicia Mazzara, “Rental Assistance Need Growing in Nearly Every State,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, May 11, 2015, https://www.cbpp.org/blog/rental-assistance-need-growing-in-nearly-every-state; and “New Census Data Show Rising Rents, Weak Income Growth,” September 18, 2015, https://www.cbpp.org/blog/new-census-data-show-rising-rents-weak-income-growth.

[7] Ehren Dohler, “The Alarming Rise in Homeless Students,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, September 15, 2015, https://www.cbpp.org/blog/the-alarming-rise-in-homeless-students.

[8] “Governor Ige Signs Emergency Proclamation to Address Homelessness Statewide,” October 16, 2015, http://governor.hawaii.gov/newsroom/governors-office-news-release-governor-ige-signs-emergency-proclamation-to-address-homelessness-statewide/; “Mayor Announces State of Emergency for Housing, Homeless,” September 23, 2015, http://www.kgw.com/story/news/politics/2015/09/23/mayor-announces-state-emergency-housing-homeless/72685832/; “L.A. to declare 'state of emergency' on homelessness, commit $100 million,” September 22, 2015, http://www.latimes.com/local/lanow/la-me-ln-homeless-funding-proposals-los-angeles-20150921-story.html.

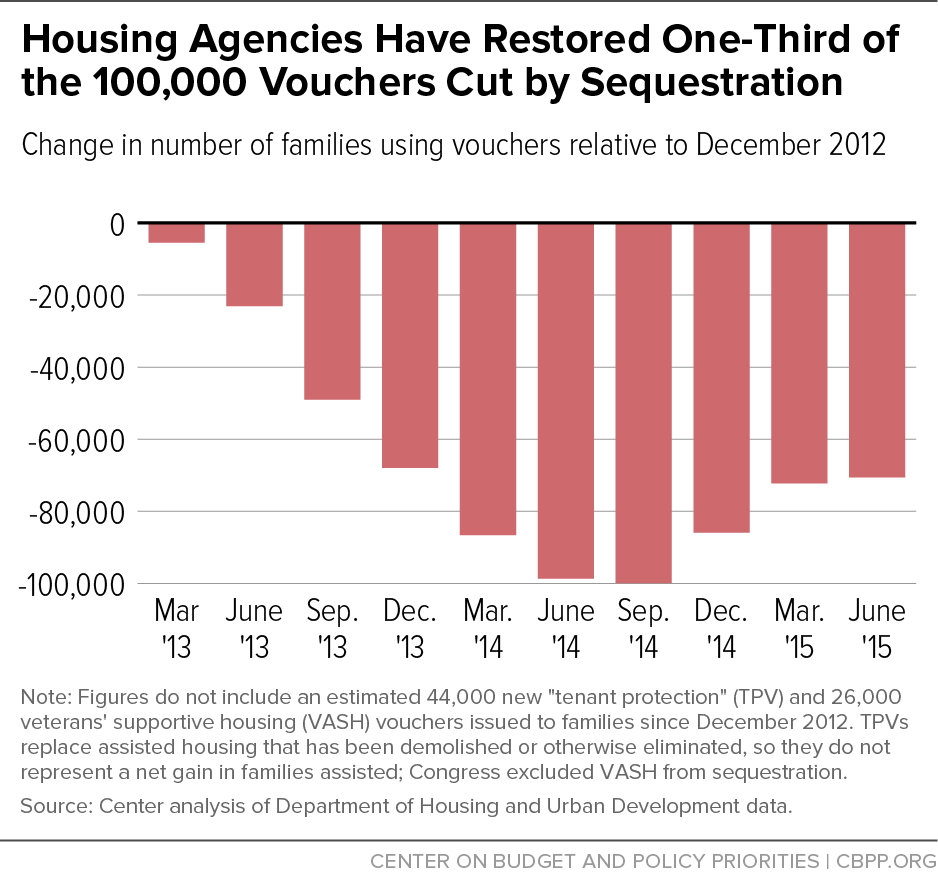

[9] Continuing an increase that began in mid-2014, about 70,000 vouchers were “on the street” during the first six months of 2015 — about 25,000 more than in the typical month before sequestration.

[10] Both bills likely include enough funding to cover agencies’ eligibility under the base renewal formula, under which eligibility for most agencies will be determined by their average voucher leasing and costs during calendar year 2015. However, agencies that restore additional vouchers in the second half of 2015 may be unable to sustain those vouchers in 2016 if the renewal funding they receive is limited to the amounts for which they are eligible under the base formula. This is why additional funds above the Senate bill level will be needed. Our estimate is based on agency-reported cost data through June 2015, and includes an inflation adjustment of 2.3 percent, which is consistent with the recent rent and utility cost trends in the private market.

[11] On the budget agreement, see Robert Greenstein, “Greenstein: Budget Deal, Though Imperfect, Represents Significant Accomplishment and Merits Support,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, October 27, 2015, https://www.cbpp.org/press/statements/greenstein-budget-deal-though-imperfect-represents-significant-accomplishment-and.

[12] The President’s budget included $512 million to restore 67,000 vouchers. Our analysis of the latest program data indicates that 60,000 vouchers would have to be restored in 2016 to fully reverse the sequestration cuts, and that this would cost $470 million.

[13] With the additional 20,000 VASH vouchers that Congress funded in 2014 and 2015, the Administration argues, communities will have sufficient capacity to eliminate homelessness among veterans who are eligible for VASH. The President’s targeted voucher proposal recognizes that some homeless veterans are unable to use VASH — for instance, because their service discharge status makes them ineligible for it or because they are in communities where VASH vouchers are not available. These veterans would be eligible for restoration vouchers.

[14] A recent HUD-sponsored survey found that only one in four housing agencies have implemented policies to ease homeless people’s access to rental assistance. Encouraging agencies to expand their efforts to reduce homelessness is essential to making progress in meeting the homelessness reduction targets the U.S. Interagency Council on Homelessness has set. HUD Office of Policy Development and Research, “Study of PHAs’ Efforts to Serve People Experiencing Homelessness,” January 2014.

[15] Patrick J. Fowler and Dina Chavira, “Family Unification Program: Housing Services for Homeless Child Welfare–Involved Families,” Housing Policy Debate, Vol. 24, No. 4 (2014), pp. 802–814.

[16] National Center for Housing and Child Welfare, http://www.nchcw.org/uploads/7/5/3/3/7533556/fup_cumulative_list.pdf.

[17] Our proposal diverges from the President’s request in one major respect. The President’s budget proposed to target only 30,000 of the 67,000 restoration vouchers on the three categories of vulnerable people described above. In contrast, we recommend targeting all of the restoration vouchers on these vulnerable groups. The Administration’s argument notwithstanding (see footnote 13), Congress could reasonably choose to set aside $75 million of the $470 million for new VASH vouchers, as the Senate bill does. In addition to restoring housing vouchers, policymakers should meet the President’s request for Homeless Assistance Grant program funding to create more than 25,000 new units of supportive housing for chronically homeless individuals, an investment that the Administration deems essential to achieving the important goal of eliminating chronic homelessness by the year 2017. Policymakers also should consider accepting the Senate bill provision for $40 million for pilot programs to investigate strategies for reducing youth homelessness.

[18] HUD Office of Policy Development and Research, Housing Choice Voucher Program Administrative Fee Study, April 2015.