More Housing Vouchers Needed to End Cycle of Homelessness and Incarceration

Safe, stable, and affordable housing remains out of reach for millions in the U.S. That is particularly true for people whose incarceration and conviction histories subject them to justice and housing policies that perpetuate cycles of homelessness and incarceration. To help address this problem long term, policymakers should make a Housing Choice Voucher available to every eligible household while reducing barriers to housing for formerly incarcerated people. At minimum policymakers should use recovery legislation to significantly expand the housing voucher program.

Vouchers have proven highly effective at keeping people with low incomes stably housed, including by reducing homelessness and overcrowding. Vouchers typically help families rent, in the private market, a modest unit they choose in the neighborhood they choose. Families pay about 30 percent of their income for rent and utilities and the voucher covers the rest, up to a cap based on estimates of local market rents.

Vouchers deliver major benefits to over 5.3 million people, more than any other rental assistance program. But they could do much more if made available to the millions now eligible but unassisted due to inadequate funding. Unlike entitlement programs such as Medicaid, rental assistance does not expand automatically to cover all who qualify. Just 1 in 4 families eligible for rental assistance receive it, and waiting lists for vouchers are years-long in much of the country.

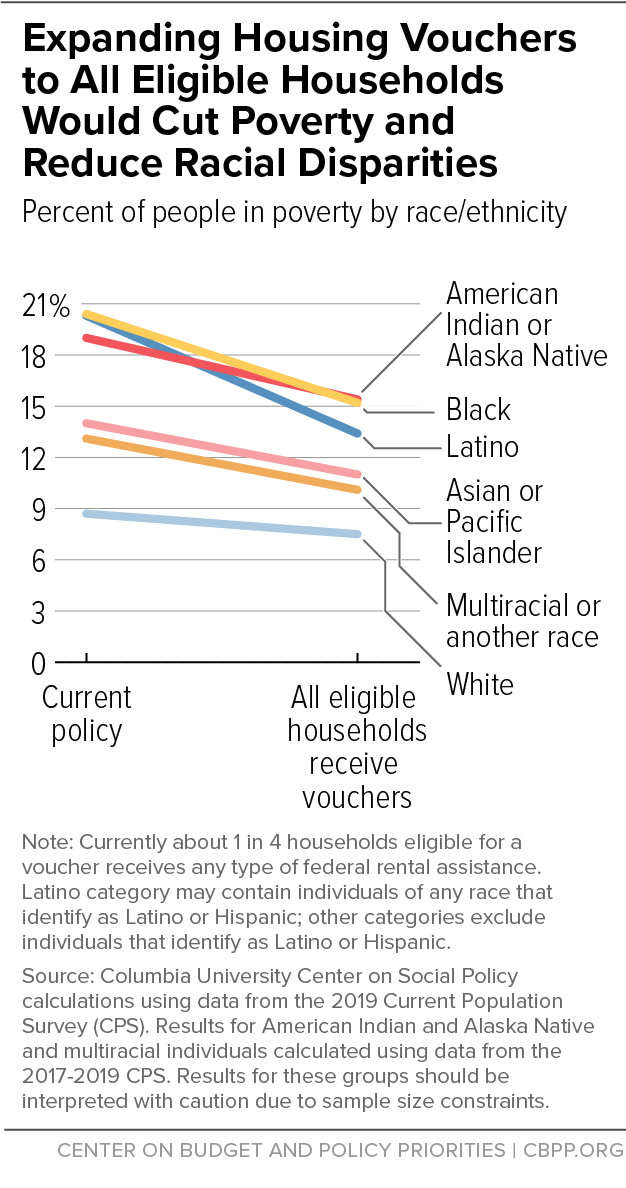

Giving all eligible households vouchers would lift an additional 9.3 million people above the poverty line, one study found, reducing the overall poverty rate by more than a fifth and the child poverty rate by over a third. Expanding vouchers would also:

1. Sharply Reduce Homelessness Among People With Histories of Incarceration or Conviction

Voucher expansion is essential to ending homelessness for people with criminal records, or those formerly incarcerated, who experience homelessness at nearly ten times the rate as the general public. Homelessness outcomes are even worse for formerly incarcerated Black people, reflecting a long history of racial discrimination and structural racism in federal, state, and local housing and criminal justice policy.

More than 50,000 people entered homeless shelters directly from jail or prison in 2017, the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) estimates, and another untold number became unsheltered following incarceration. Homelessness makes it difficult to avoid reincarceration, including by making it harder to comply with court mandates. People experiencing homelessness often lack access to reliable mailing addresses, a phone, or a computer to stay in contact with probation or court officials, increasing their likelihood of missing hearings or court-ordered substance use treatment sessions and of being issued arrest warrants. Homelessness is especially high among people incarcerated more than once.

For most people, rental assistance and short-term support in navigating the rental market is enough to provide long-term housing stability. However, some people with criminal records or returning from incarceration will need supportive housing, an evidence-based solution that pairs rental assistance with supportive services such as intensive case management, ongoing housing navigation, and physical and behavioral health services for those who want them. In addition to providing stable housing, supportive housing can improve access to appropriate health care, reduce use of costly systems like emergency health services, and reduce reincarceration. This is critical as people who are incarcerated have higher rates of mental illness, substance use disorders, and chronic physical health conditions. But they often go without needed health care while incarcerated and return home without adequate access to medications or other health care services.

Vouchers are particularly well-suited for increasing access to supportive housing. Vouchers can be tenant-based, letting people choose a unit on the private market, or project-based, meaning the rental assistance is attached to specific units. If vouchers were readily available, this flexibility would help communities create a variety of housing options — including supportive housing — so that people returning from jail or prison can choose housing that meets their needs.

2. Reduce the Criminalization of Homelessness

Some communities deploy local law enforcement strategies that effectively criminalize homelessness by ticketing or arresting people for sleeping outside, living in cars, or asking members of the public for money or food. These counterproductive policies subject people to fines or jail time for being unable to afford a place to live. For instance, a person ticketed for simply sleeping on a bench might not be able to afford related fees or fines or receive court notices, which could lead to incarceration and further charges.

Criminalization of homelessness can also make it harder for people to access housing. HUD has cautioned that landlords cannot deny housing solely based on an arrest that did not result in conviction. However, housing providers in most communities do have significant discretion to deny housing to people because of a criminal conviction.

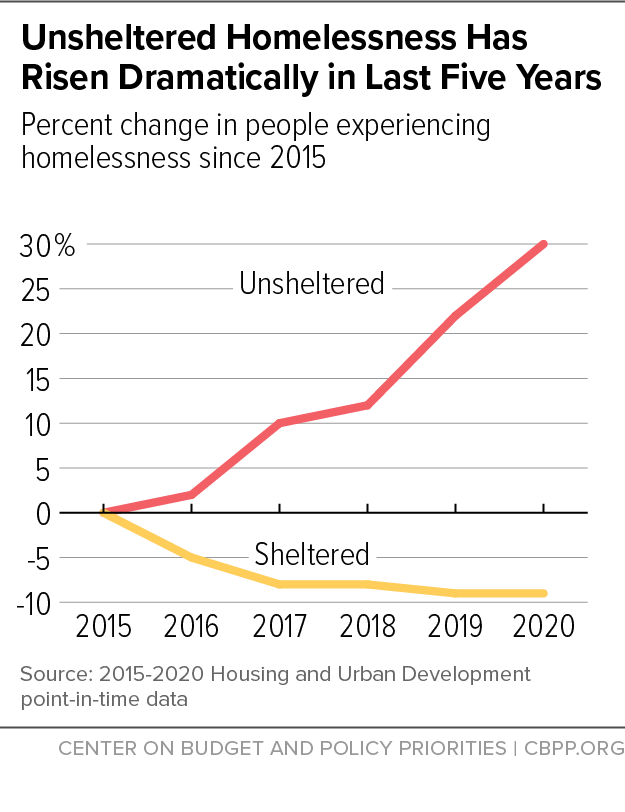

In 2020, even before the pandemic, homelessness rose in 30 states from one year earlier and, for the first time since HUD began tracking the data, more single individuals experienced unsheltered homelessness than sheltered. (See Figure 1.) Communities with overwhelmed shelter systems and recent rises in unsheltered homelessness may be tempted to address the problem with counterproductive law enforcement approaches. Expanding housing vouchers would provide communities with a much more humane, effective, and sustainable solution to unsheltered homelessness.

3. Advance Racial Equity and Help Prevent Incarceration

The housing needs of low-income people leaving jail and prison have long gone unmet, compounding the harmful effects of mass incarceration and over-policing of communities of color. Stable housing greatly improves people’s chances of staying out of jail and prison after reentry, but 3 in 4 low-income renters in need of federal rental assistance do not receive it due to funding limitations. Moreover, public housing agencies that administer rental assistance and private landlords often turn away applicants with conviction records, making it even more difficult for people with conviction histories to locate and afford housing. The lack of resources disproportionately harms people of color — particularly Black and Latinx people — and people with disabilities, who are overrepresented in the criminal legal system.

Expanding vouchers would help more people leaving jail and prison secure stable housing and also reduce poverty. Adults with low incomes are much more likely to be arrested and to receive a harsher sentence. Expanding vouchers to all eligible households would cut the poverty rate by a third for Latinx people, by a quarter for Black people, and by a fifth for Asian people and Pacific Islanders and for American Indians and Alaska Natives. (See Figure 2.) Affordable housing would mean that people returning from incarceration and their families have more money left over to cover other basic needs, like food or medicine, and invest in their future, such as by searching for employment.

Additional vouchers would have an even greater impact if paired with state, local, and federal efforts to reduce barriers to federal rental assistance for people with conviction records. In June HUD Secretary Marcia Fudge sent a letter to public housing agencies and other HUD funding recipients expressing her agency’s commitment to improving housing access for people with conviction histories. The letter highlights opportunities for public housing agencies to use emergency vouchers under the American Rescue Plan Act to prevent homelessness among people leaving jail and prison, especially for those who have previously experienced homelessness. The letter also previews potential HUD actions to reduce barriers to assistance, building on work already underway in communities such as New Orleans and New York City to revamp public housing agencies’ screening policies.