More Housing Vouchers Needed for People With Behavioral Health Challenges

Safe, stable, and affordable housing remains out of reach for millions in the U.S., which can undermine their mental well-being and access to behavioral health care. People with behavioral health conditions such as a mental illness or substance use disorder are also at greater risk of homelessness, which can exacerbate symptoms. To address these problems long term, policymakers should make a Housing Choice Voucher available to every eligible household. At minimum they should use recovery legislation to significantly expand the program.

Vouchers have proven highly effective at keeping people with low incomes, including those with behavioral health conditions, stably housed. Vouchers typically help families rent, in the private market, a modest unit they choose in the neighborhood they choose. Families pay about 30 percent of their income for rent and utilities and the voucher covers the rest, up to a cap based on local market rents.

Vouchers deliver major benefits to over 5.3 million people, more than any other rental assistance program. But they could do much more if made available to the millions now eligible but unassisted due to inadequate funding. Unlike entitlement programs such as Medicaid, rental assistance does not expand automatically to cover all who qualify. Just 1 in 4 families eligible for rental assistance receive it, and waiting lists for vouchers are years-long in much of the country.

Many states and communities have funded their own, smaller rental assistance programs for people with behavioral health challenges who are experiencing or at risk of homelessness, but they don’t come close to closing the gap in need. Expanding the federal voucher program would help scale up these efforts.

Giving vouchers to everyone eligible would lift 9.3 million people above the poverty line, one study estimated. That likely includes many of the million-plus people with a serious mental illness who receive Supplemental Security Income (SSI); at $794 for individuals in 2021, this modest basic monthly benefit — the only source of income for over half of recipients — is too little to pay for a typical one-bedroom apartment. In addition to helping these SSI recipients, expanding the voucher program would:

1. Sharply Reduce Homelessness for People With Behavioral Health Conditions

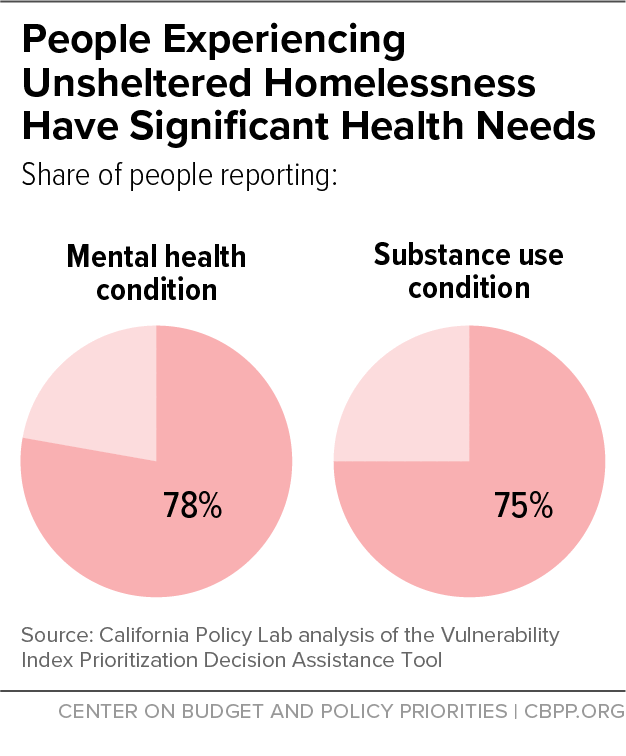

Voucher expansion is essential to ending homelessness for people with behavioral health conditions. For the first time since these data were collected, in January 2020 more individuals experiencing homelessness were unsheltered — which is associated with high rates of mental health and substance use disorders — than sheltered. (See Figure 1.) And chronic homelessness, that is, extended or repeated homelessness among people with a disabling condition such as serious mental illness, is on the rise.

Rental assistance and short-term support in navigating the rental market are enough for most people to regain long-term housing stability. However, some people with behavioral health challenges will need supportive housing, an evidence-based solution that pairs rental assistance with supportive services such as intensive case management, ongoing housing navigation, and physical and behavioral health services for those who want them. In addition to providing stable housing, supportive housing can improve access to quality health care, reduce use of costly systems like emergency health services and psychiatric facilities, and reduce incarceration.

Vouchers are particularly well-suited for increasing access to supportive housing. Vouchers can be tenant-based, letting people choose a unit on the private market, or project-based, meaning the rental assistance is tied to specific units. Having vouchers readily available would help communities create a variety of integrated housing options — including supportive housing — so that people with behavioral challenges can choose one that meets their needs without being isolated from the community.

2. Support People’s Mental Health

Homelessness and housing instability — such as frequent moves, eviction, or overcrowding — can worsen mental health. For instance, in April-July 2020 survey data, people who reported low confidence in their ability to pay rent during the pandemic reported worse mental health and greater mental distress than those confident they could keep up with rent. And mothers of young children who were recently evicted report significantly higher levels of depression and parenting stress. Research also finds that people without stable housing are more likely to postpone care due to costs and are less likely to have a regular source of health care.

The emotional toll of housing instability falls heavily on people of color due to our nation’s long history of discriminatory policies that created disparities in education, employment, and housing. Renters of color have been more likely to report that their household was not caught up on rent during the pandemic, and Black and Latina women face disproportionately high eviction rates.

Expanding vouchers would provide more families with housing stability, reducing stress and barriers to mental health care. Rental assistance sharply reduces psychological distress among adults in homeless families, studies find. Reducing homelessness and housing instability could also help prevent trauma and adverse childhood experiences that can lead to worse behavioral health among youth and adults. In addition, when families use vouchers to move to lower-poverty neighborhoods, adults can experience better mental health and other major health improvements. More vouchers could also help interrupt the cycle between psychiatric hospitalization and homelessness; studies show that providing people transitioning out of inpatient psychiatric care with secure, stable housing can improve access community-based services and reduce the likelihood of future hospitalization.

3. Help Address the Substance Use Crisis

Stable, affordable housing is critical for substance use disorder (SUD) recovery and access to care. The inability to pay rent and the threat of losing housing cause stress that can contribute to substance misuse and relapse. People transitioning out of inpatient treatment, residential care, or transitional recovery housing who can’t secure affordable housing may be forced into homeless shelters or crowded living environments that undermine their recovery and make it harder to participate in community-based services.

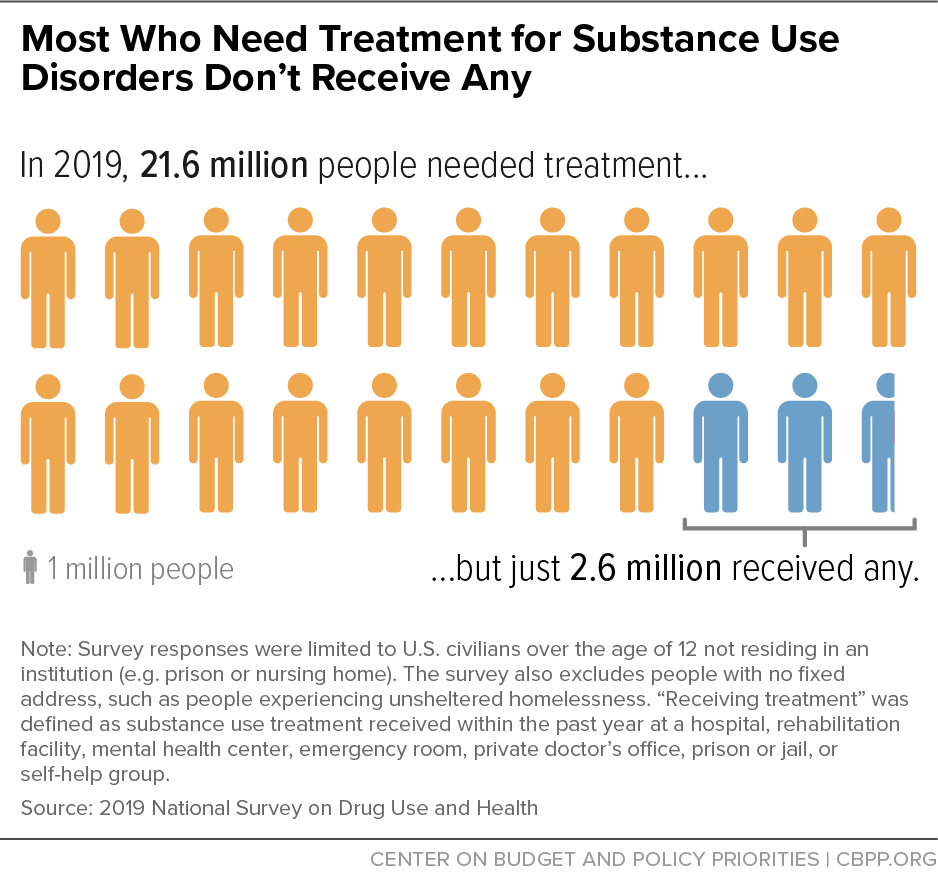

Drug overdose deaths rose dramatically over the last 20 years: from fewer than 20,000 in 2000 to over 71,000 in 2019. Preliminary data suggest that the rise in deaths accelerated during the pandemic and likely reached an all-time high of over 90,000 in 2020. Yet fewer than 13 percent of the 21 million-plus people who need SUD services get any. (See Figure 2.) While improved access to substance use coverage and services requires investments such as leveraging the Affordable Care Act’s Medicaid expansion, it also requires meeting basic but unmet needs such as housing.

Expanding vouchers will provide more people struggling with SUDs with stable housing, which many people need before they can focus on their recovery or engage in treatment. Research shows that rental assistance given to families experiencing homelessness can reduce alcohol and drug use among adults. More vouchers would also provide housing stability to people in recovery — including people who want to transition out of recovery housing — thereby helping reduce stressors that could contribute to relapse. Vouchers can also help families affected by SUDs live in neighborhoods that best meet their needs, such as near services or social supports. Vouchers may be particularly important for people of color with SUDs, who often face more limited housing choice due to discrimination and to policies that led to community segregation and underinvestment.