Policy Brief: More Housing Vouchers Most Important Step to Help More People Afford Stable Homes

As the economy recovers from the COVID-19 crisis, high housing costs will continue to cause hardship for millions of renters with low incomes, raising their risks of housing instability and homelessness and impeding their children’s chances of long-term success.[1] The recovery legislation that policymakers will consider soon is a historic opportunity to address this problem. Providing Housing Choice Vouchers to more households — and ultimately to all who are eligible, as President Biden proposed during the presidential campaign — is by far the most important step they can take.

Millions of U.S. households with low incomes must pay very high shares of those incomes in order to afford housing. The costs can force families to divert resources from other basic needs and leave them one setback — such as a reduction in work hours or an unexpected bill — away from losing their homes. Many others live in housing that is overcrowded or substandard, in shelters, or on the streets. These problems are linked to harm in other aspects of families’ lives, including children’s health, development, and education.

Federal rental assistance — and especially Housing Choice Vouchers, the largest rental assistance program — offers a proven, evidence-based tool that could be scaled up to help more people struggling to afford housing and prepare the nation for future crises. Vouchers help more than 2 million low-income households afford decent, stable housing, usually by helping them rent a modest unit of their choice in the private market. Housing vouchers are highly effective at reducing homelessness, housing instability, and overcrowding and at improving other outcomes for families and children, rigorous research shows. Stable housing has cascading benefits in other parts of the lives of low-income people, particularly for children. And by giving people with low incomes greater choice about where they live, vouchers have major additional benefits when they enable families to move to lower-poverty, better-resourced neighborhoods.

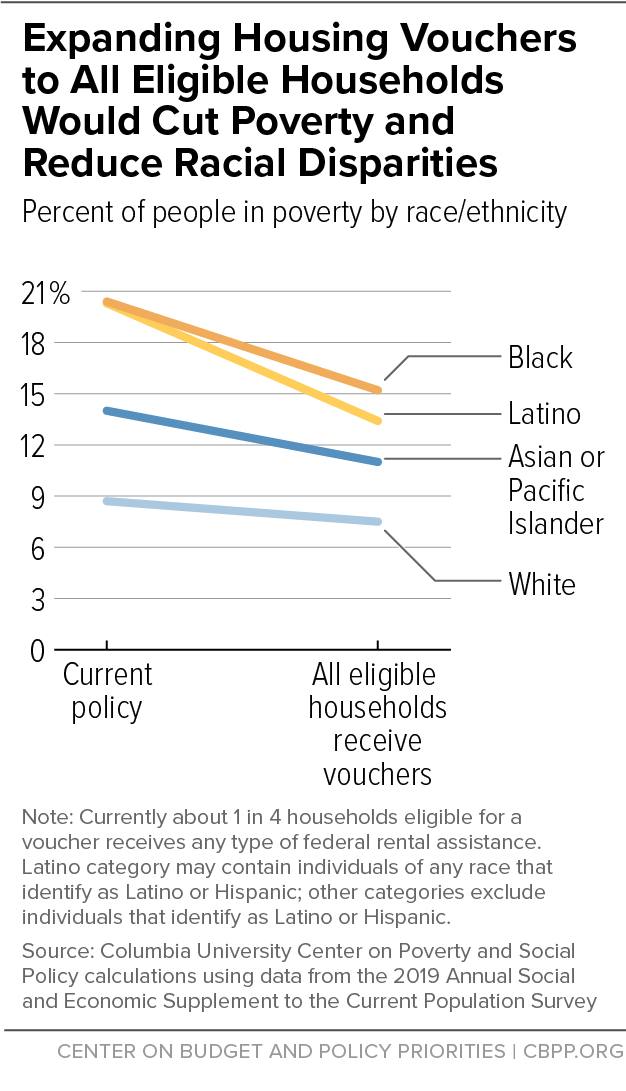

Vouchers can also make a major contribution to lifting people out of poverty and reducing racial inequity: the housing affordability challenges that vouchers address are heavily concentrated among people with the lowest incomes and, due to a long history of racial discrimination that has limited economic and housing opportunities, people of color. One study estimated that giving all eligible households vouchers would lift 9.3 million people above the poverty line and cut the child poverty rate by a third, as well as lower the gap in poverty rates between white and Black households by over a third and between white and Hispanic households by nearly half.

But due to inadequate funding, just 1 in 4 voucher-eligible families received any type of federal rental assistance even before the pandemic struck, and there are long waiting lists for vouchers in much of the country. These inadequacies leave families struggling to keep a roof over their heads even in good economic times. And they are a major reason why adequate, timely housing assistance wasn’t available as need grew in the COVID-19 crisis.

A top priority in recovery legislation should be to provide vouchers to a larger share of families in need. To do so, policymakers would almost certainly need to change the program’s funding mechanism. Today vouchers receive “discretionary” funding; lawmakers determine the funding level each year in appropriations bills. By contrast, most of the largest federal programs that help low-income households meet basic needs receive “mandatory” funding, which is set at levels determined by ongoing laws rather than by annual appropriations. Mandatory appropriations would let lawmakers decide how much to invest in housing vouchers over a multi-year period and would be essential to enabling the program to expand automatically when people need more help.

Policymakers should also increase funding to build and rehabilitate affordable housing. But only funding these “supply side” investments, without adequately expanding vouchers, would almost certainly leave out a large share of those who most need help to afford housing. Construction subsidies rarely produce homes with rents affordable for households with incomes around or below the poverty line unless the household also receives a voucher or similar ongoing rental assistance.

Making more vouchers available would mean that fewer people would live in shelters or motels, on the street, or in overcrowded homes; fewer families, seniors, and people with disabilities would have to choose each month between paying the rent and buying needed medicine or food; and more children would have access to stable housing in neighborhoods their parents choose. Taken together, these benefits could substantially reduce low-income households’ exposure to hardship and improve their children’s chances of long-term success, while also preparing the nation to respond more promptly and humanely to housing needs during the next health or economic crisis.

End Notes

[1] The full version of this report is available at https://www.cbpp.org/research/housing/more-housing-vouchers-most-important-step-to-help-more-people-afford-stable-homes.

More from the Authors