BEYOND THE NUMBERS

Policymakers can best help renters afford stable housing during the current crisis and beyond by making Housing Choice Vouchers available to more low-income people — and ultimately to all households that need them, as President Biden has proposed.

To help renters keep a roof over their heads through COVID-19 and the economic downturn, the next pandemic relief package should provide emergency, short-term rental assistance and a sizable number of new Housing Choice Vouchers, and policymakers should extend the federal moratorium on evictions that is now scheduled to expire at the end of March. But millions of people struggled with homelessness, evictions, overcrowding, and unaffordable rents even before the current crisis caused many renters to lose their jobs, so addressing the underlying need requires more permanent measures. Policymakers should enact legislation to phase in a universal voucher program — or failing that, to provide as large an expansion of the voucher program as possible.

Before the pandemic, 7.7 million households with incomes under half the local median level paid over 50 percent of their income for rent or lived in substandard housing, partly because rents have grown faster than renters’ incomes in recent decades. Many other low-income people live in overcrowded homes that make them especially vulnerable to infection, and more than 500,000 were homeless on a single night in January 2019. The pandemic and economic downturn have exposed many more people to housing insecurity: 1 in 5 renters reported this month that they weren’t caught up on their rent. These problems are heavily concentrated among people with incomes under the poverty line and people of color.

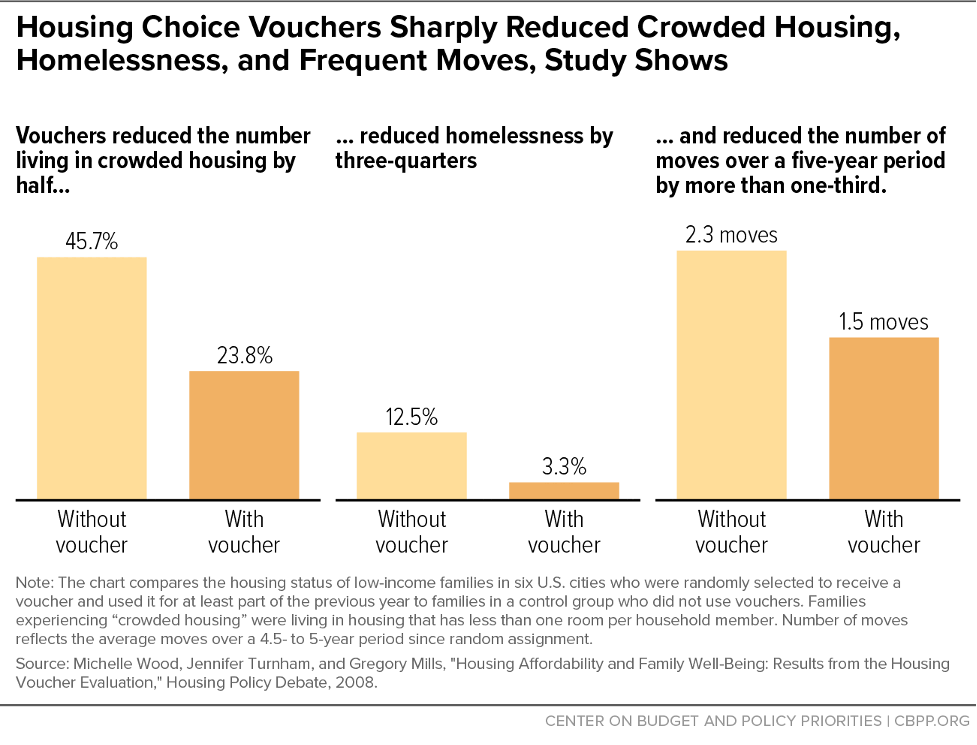

We know what works to address these challenges: vouchers sharply reduce homelessness, housing instability, and overcrowding, rigorous research shows. In addition, children in families experiencing homelessness who receive rental housing vouchers need to change schools less frequently, are less likely to be placed in foster care, and experience fewer sleep disruptions and behavioral problems than children from otherwise-similar families that don’t receive vouchers. By lowering rental costs, vouchers also enable low-income people to spend more on other basic needs like food and medicine, as well as on goods and services that enrich their children’s development.

Unfortunately, vouchers and other federal rental assistance only reach 1 in 4 eligible families due to inadequate funding. Because of this shortfall — one of the biggest gaps in the nation’s safety net — families with pressing housing needs face long waiting lists for vouchers that sometimes stretch for years.

Providing vouchers to all who need them would do more than any available option to reduce homelessness, housing instability, and overcrowding. It also would significantly reduce poverty and racial inequities.If vouchers reached all eligible households, a recent Columbia University study found, they’d lift 9.3 million people out of poverty, reduce child poverty by a third, and narrow the gap in poverty rates between white and Black households by over a third. Similarly, a National Academy of Sciences panel identified a major voucher expansion as part of a package of policies that would sharply lower child poverty and reduce the gap in poverty rates between white children and Black and Latino children.

A universal voucher program also would better prepare the nation to handle the next health or economic crisis by reducing the number of people living in vulnerable arrangements such as overcrowded housing, shelters, or the streets. And, if policymakers made Housing Choice Vouchers an entitlement program like Medicaid and SNAP — meaning that the program would automatically assist all eligible applicants — it would scale up automatically when the number of families struggling to afford rent grows. That would help families before they accumulate backlogs of unpaid rent and reduce the need for policymakers to design temporary relief programs during an emergency.

To be sure, more vouchers alone won’t fully address the nation’s housing needs. Especially in tight housing markets where housing supply is inadequate, policymakers should ease regulatory barriers to building homes and subsidize more affordable housing, both public and privately owned. And we need steps such as robust enforcement of fair housing laws to enable voucher holders and others to choose among homes in a wide range of neighborhoods. But those other policies aren’t enough to make housing affordable to families with the lowest incomes. Vouchers are by far the best way to accomplish that goal.