The economic recovery legislation now being developed in Congress (also known as “Build Back Better”) would fund as many as 750,000 new Housing Choice Vouchers to help people with low incomes afford stable housing, at the end of a five-year phase-in.[1] The voucher expansion only amounts to about one-fifth of the recovery bill’s investment in housing, which is largely focused on subsidies to build or renovate housing.[2] But the vouchers — which we estimate would assist 1.7 million people when fully phased in, including 660,000 children, 180,000 seniors, and 330,000 people with disabilities — would do more than any other housing policy in the legislation to reduce homelessness and other hardship for people who struggle most to afford a home:

- An extensive body of research shows that these new vouchers, which would be tightly targeted on families and individuals who need them most, would sharply reduce homelessness, housing instability, and overcrowding. By helping families obtain stable housing, vouchers also have other proven benefits for children (such as a lower likelihood of being placed in foster care, fewer school changes, and fewer sleep disruptions and behavioral problems) as well as adults (such as lower rates of domestic violence and drug and alcohol abuse).

- Vouchers would reduce the large racial disparities in housing opportunity, which reflect longstanding discrimination in housing, employment, and other areas. Some 71 percent of those assisted by the vouchers would be people of color. Vouchers would also give families (including families of color, who often have faced discriminatory rental practices and zoning laws that limit their housing choices) broader choice about where they live. Studies show that when vouchers enable families to move to high-opportunity areas, both children and adults can benefit over the long term.

- While construction and renovation subsidies have an important role to play, they rarely make rents affordable to the lowest-income households unless the household also receives a voucher or other rental assistance. Without the additional rental assistance the bill would provide, therefore, the recovery bill’s subsidies to increase the housing supply could end up doing little to help the families who have the greatest difficulty affording housing. The rental assistance in the bill — both vouchers and separate funding to expand other programs such as Section 8 Project-Based Rental Assistance — would help make units affordable to families with incomes around or below the poverty line, including in units built with the bill’s renovation and capital subsidies.

- Rental markets could readily absorb the bill’s new vouchers. The number of units needed would be small compared to the overall size of the nation’s rental stock, and many of the new vouchers would likely go to households that already rent housing but pay very high shares of their income for rent. Also, the number of families currently helped by Housing Choice Vouchers is limited by inadequate funding, not a shortage of units; in recent years housing agencies have used virtually all of the voucher funding they have received.

As the bill advances through the legislative process, lawmakers should place a high priority on retaining the voucher expansion along with other investments that benefit people with the greatest need for housing assistance, such as public housing renovations, the national Housing Trust Fund, tribal housing, and Project-Based Rental Assistance.

As Congress moves to finalize the recovery package, tough trade-offs may be necessary. In this context, it is important to recognize the impact that reducing voucher funding levels would have. For every $5 billion reduction in the bill’s funding for vouchers, we estimate that 112,000 people who would have received voucher assistance once the expansion is fully in place will be left unassisted, greatly increasing the chances that they will experience homelessness, eviction, and other severe hardship. This would include 44,200 children, 22,100 people with disabilities, and 12,100 seniors. Some 79,100 of those denied assistance as a result of such a reduction would be people of color.[3]

The part of the economic recovery package passed by the House Financial Services Committee on September 13 provides $75 billion to expand the Housing Choice Voucher program, which provides participants with vouchers they use to rent modest housing of their choice in the private market. The bill directs the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) to phase in the expansion over the 2022-26 period by allocating some of the new vouchers to state and local housing agencies each year. The exact number of added vouchers would depend on how HUD implements the expansion, but the funding is sufficient to assist about 150,000 additional households each year, for a total of 750,000 once the expansion is fully phased in, assuming the funds are used to cover the cost of the vouchers through 2031.[4] Today vouchers help nearly 2.3 million households afford housing, so the expansion could increase that number by close to a third.

Most of the new vouchers (about 545,000) would be available to any household that has what HUD labels as “extremely low income” — below the federal poverty line or below 30 percent of the local median income, whichever is higher. Data show that extremely low-income households are far more likely than higher-income households to struggle to afford housing. The remaining vouchers (about 205,000) would be set aside for people with a particularly urgent need for housing assistance: those experiencing or at risk of homelessness and survivors of domestic violence and trafficking. The bill also sets aside $750 million for “mobility assistance” to help families with children and other households rent housing in a wide range of neighborhoods and $500 million for measures to encourage landlords to rent to voucher holders.

The Appendix tables show estimates of how many households the 750,000 vouchers would benefit in each state, with breakdowns by race and other demographic groups. We estimate that the households assisted include roughly 1.7 million people, among them 660,000 children, 180,000 seniors, and 330,000 people with disabilities. Some 71 percent of those assisted would be people of color; housing needs are heavily concentrated among people of color due to a long history of discrimination in housing, employment, and other areas.

The recovery bill’s voucher expansion is well designed to address the nation’s most pressing housing problem: millions of people don’t have enough income to afford safe, stable housing. Even before the pandemic and economic downturn, 24 million people in low-income households paid more than 50 percent of their income for rent. (Government programs and private owners and lenders often use 30 percent of income as a benchmark for the amount households can afford to pay for housing.)

Typically, renters who must pay very high shares of their income for housing have to divert money away from other necessities to keep a roof over their heads, such as by going without needed food, medicine, clothing, or school supplies. As those unmet needs pile up, families often find themselves one setback — a cut in their work hours or unexpected bill — away from eviction. Unaffordable housing also compels many people with low incomes to live in homes that are overcrowded or unsafe, which can seriously harm children’s health and well-being. And hundreds of thousands of people can’t afford a home at all; 580,000 people slept in shelters or on the streets on the night in January 2020 when HUD conducted its annual point-in-time homeless count.

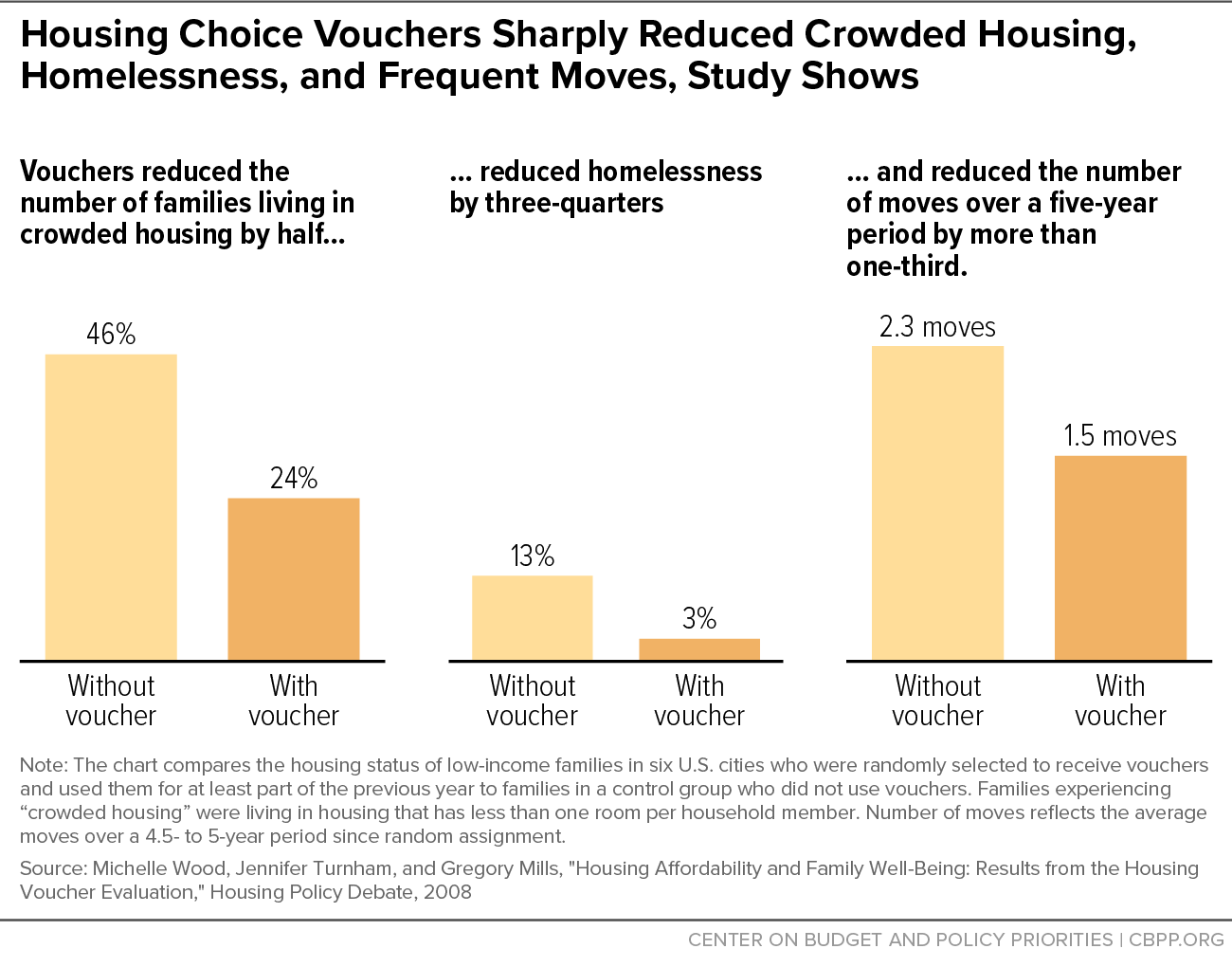

Housing vouchers are the most direct, effective way to take on these problems. Research shows that vouchers sharply reduce homelessness, overcrowding, and housing instability. (See Figure 1.) And because stable housing is crucial to many other aspects of a family’s life, those same studies show numerous additional benefits. Children in families with vouchers are less likely to be placed in foster care, switch schools less frequently, experience fewer sleep disruptions and behavioral problems, and are likelier to exhibit positive social behaviors such as offering to help others or treating younger children kindly. Among adults in these families, vouchers reduce rates of domestic violence, drug and alcohol abuse, and psychological distress.[5]

The recovery bill’s voucher expansion would be especially likely to be effective at reducing hardship and improving other outcomes because the vouchers would be well targeted on people who need them. This is especially true of the 205,000 vouchers that would be set aside for people who are experiencing or at risk of homelessness and survivors of domestic violence and trafficking; the bill will be more effective at reducing homelessness and other severe hardship if this set-aside is retained. But even outside of this set-aside, the new vouchers would go entirely to households with incomes around or below the poverty line, which are far more likely than higher-income households to pay very high shares of their income for rent and be at risk of losing their homes as a result.

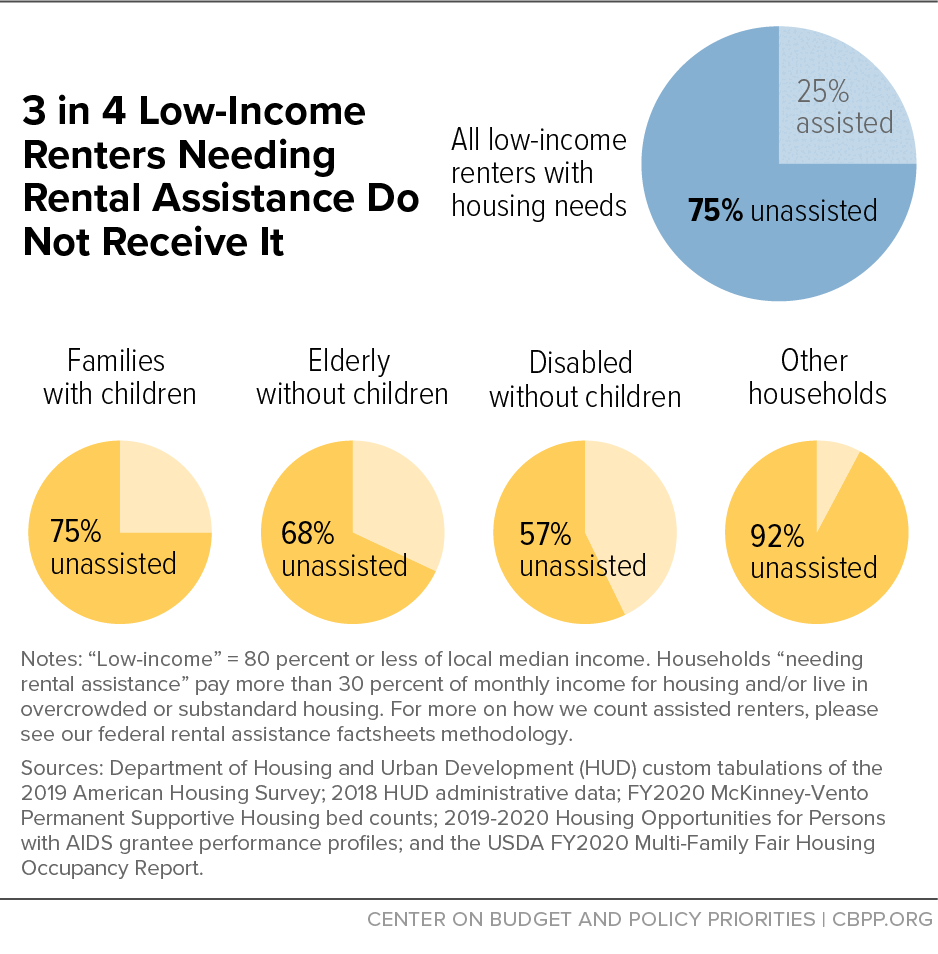

Despite their far-reaching benefits, housing vouchers have long been deeply underfunded. Only 1 in 4 households eligible for a voucher receive any type of federal rental assistance,[6] and in much of the country, families applying for vouchers must wait years before receiving them, if they receive them at all.[7] (See Figure 3.) The recovery bill’s voucher expansion would not provide a voucher to everyone who is eligible (though President Biden and a number of members of Congress have committed to reaching this goal over time); nor would it end homelessness, housing instability, and overcrowding. But it would be the most important step policymakers have taken in decades toward each of those goals and would provide hundreds of thousands of families and individuals with relief from some of the most severe hardship in the United States today.

Due to a long history of racial discrimination in housing and other areas, the problems that vouchers address are disproportionately concentrated among people of color. More than 60 percent of people in low-income households that pay more than half their incomes for housing are people of color. Also, nearly 40 percent of those who experienced homelessness in 2020 were Black and 23 percent were Latino, far above these groups’ shares of the U.S. population (13 and 18 percent, respectively). People of color also disproportionately face other severe forms of housing-related hardship, including evictions and overcrowding.

Expanding rental assistance can sharply reduce these racial disparities. For example, one study estimated that providing vouchers to all eligible households would lift 9.3 million people out of poverty, using a measure of poverty that counts in-kind benefits such as rental assistance as income. Poverty rates would drop for all racial and ethnic groups but most among Black and Latino households, reducing the gap in poverty rates between Black and white households by a third and the gap between Latino and white households by nearly half. The recovery bill’s more limited voucher expansion would reduce these disparities by smaller but still substantial amounts. Similarly, people of color would be particularly likely to benefit from the reductions in homelessness, overcrowding, and evictions and other housing instability that the added vouchers would bring about.[8]

Racism has also prevented many people of color from choosing what community or neighborhood to live in, as federal, state, and local policies ranging from discriminatory lending rules to exclusionary zoning that prevented development of low-cost housing have blocked Black people and others from moving to areas with predominantly white populations. Moreover, due to neglect by public officials and other factors, many neighborhoods with large shares of people of color suffer from high poverty rates, poorly performing schools, unhealthy environmental conditions, and lack of other services and amenities. Despite antidiscrimination measures such as the 1968 Fair Housing Act, housing discrimination and local government policies that reinforce segregation remain widespread.

Housing vouchers can provide people with low incomes — including people of color — with more choice about where they live. They can do so even more effectively if families also receive mobility assistance such as search counseling, outreach to landlords on their behalf, and help with costs such as security deposits and application fees to help them rent a home in a neighborhood of their choice. Families with vouchers are much more likely — in one study, nearly four times as likely — to be able to move to high-opportunity neighborhoods if they receive mobility assistance.[9] But even without any special assistance, among Black children in households with incomes below the poverty line, children whose families use a voucher are twice as likely as children overall to live in a neighborhood with a low poverty rate.

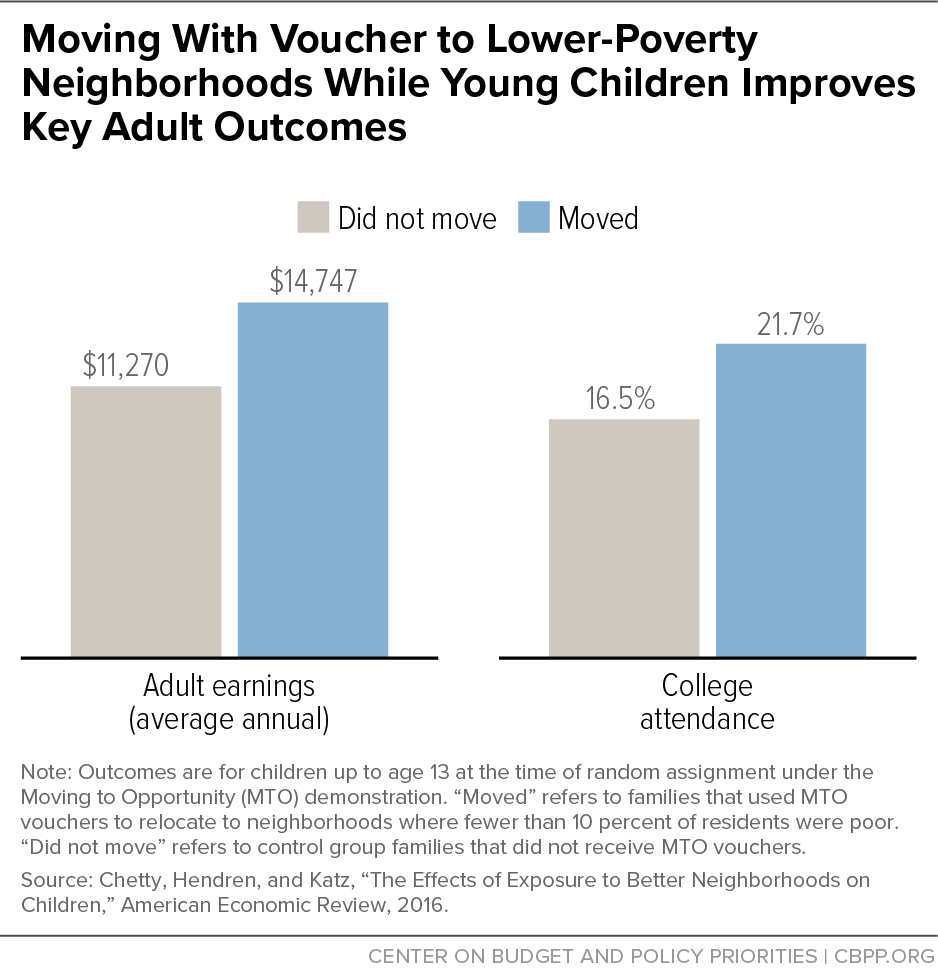

Other research demonstrates that when vouchers enable families to move to high-opportunity areas, this can have powerful positive effects. A rigorous long-term study found that children whose families used vouchers to move from high- to low-poverty neighborhoods had substantially higher adult earnings and rates of college attendance than similar children whose families stayed in poorer neighborhoods.[10] (See Figure 3.) Adults in these families had improved mental health and lower rates of diabetes and extreme obesity; researchers concluded that these outcomes may partly reflect lower stress due to reduced exposure to crime. Positive effects like these are on top of the benefits from receiving a voucher regardless of what neighborhood the family lives in, such as less overcrowding and housing instability.

The recovery bill’s voucher expansion is its most important housing provision, since it would do more than any other measure in the bill to help people who experience homelessness, overcrowding, or other severe housing-related hardship. But vouchers only account for a small share of the bill’s total investment in housing, which also includes $327 billion through the Financial Services Committee’s portion of the bill and $47 billion for housing tax subsidies under the jurisdiction of the Ways and Means Committee.[11] The bulk of the Financial Services funding and all of the housing tax subsidies would go toward building or rehabilitating housing.

These supply-side investments can accomplish important goals, including increasing the housing supply in tight markets, improving energy efficiency, addressing health and safety risks such as lead paint, and making more units accessible to people with disabilities. Investments that prioritize construction or rehabilitation of housing set aside for the lowest-income households and other underserved groups can be particularly beneficial, such as the bill’s $80 billion for urgently needed renovations to public housing (which could help preserve many of the nation’s 1 million public housing units as housing affordable to the lowest-income people), $37 billion for the national Housing Trust Fund, and $2 billion for tribal housing and community development programs.

But most supply investments in the bill would not make housing affordable to households with incomes around or below the poverty line unless the household also received a voucher or other similar ongoing rental assistance. This is a serious limitation, since more than 70 percent of households that pay over half their income for rent have extremely low incomes, and these households are far more likely than higher-income households to experience homelessness and other housing-related hardship. One reason supply investments alone are rarely enough to enable the lowest-income households to afford housing is that these households typically can’t afford rent set at a high enough level for an owner to cover the ongoing cost of operating and managing housing. Consequently, even if development subsidies pay for the full cost of building housing, rents in the new units will generally be too high for lower-income families to afford without the added, ongoing help a voucher can provide.[12]

For example, the largest federal affordable housing development program, the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC), allows rents to be set up to levels affordable to families with incomes at 60 percent of the local median. In many areas this is more than 200 percent of the poverty line.[13] LIHTC developments house many families with incomes around or below the poverty line, but nearly all either pay high shares of their income for rent or receive a voucher or similar rental assistance that enables them to afford the unit.[14]

The rental assistance funding in the bill is essential to enabling people with the lowest incomes to afford housing, including in buildings that would be built or renovated through the bill’s development subsidies. Both vouchers and other rental assistance funded through the bill could reduce rents in housing that receives development subsidies to a level that families with incomes around or below the poverty line can afford.

Vouchers could play this role in two different ways. First, most vouchers are “tenant-based,” meaning they can be used in a modest unit of the family’s choice. Federal law prohibits owners of most buildings that receive federal development subsidies from discriminating against voucher holders, so a family with a tenant-based voucher could opt to use it in such a development or elsewhere.

Second, housing agencies can also enter into long-term “project-basing” agreements that require some vouchers to be used in a particular development. A family living in a project-based voucher unit is permitted to move with the next available tenant-based voucher after one year, and a new family from the voucher waiting list then moves into the project-based voucher unit. Normally, an agency can project-base up to 30 percent of its vouchers (with exceptions allowing agencies to go higher under certain circumstances). But the recovery bill would give HUD discretion to exempt the vouchers the bill would fund from that limit, so agencies could potentially project-base substantially more than 30 percent of the new vouchers.

In addition to vouchers, the recovery bill would also expand other federal rental assistance programs, most importantly through $15 billion for added subsidies under the Section 8 Project-Based Rental Assistance (PBRA) program. PBRA provides assistance through long-term contracts between HUD and building owners, and the PBRA funding in the recovery bill would be targeted on owners or prospective owners who agree to build or substantially rehabilitate housing (although not necessarily with the development subsidies the bill provides). Residents of PBRA units generally cannot move without giving up their subsidies, so they have less choice about where they live than project-based voucher residents.

At least 40 percent of households that move into a PBRA project each year must have extremely low incomes and all must have incomes below 80 percent of the area median income. PBRA units thus are not as tightly targeted as the recovery bill’s vouchers (all of which would have to be used for households that have extremely low incomes, are experiencing or at risk of homelessness, or are survivors of domestic violence or trafficking) but could nonetheless play a substantial role in making some units affordable to the lowest-income families. And there will be a pressing need for both the PBRA and voucher funding included in the bill, since even combined they would only reach a portion of households needing rental assistance.

A housing investment package focused disproportionately on development would also limit the housing choices available to low-income renters. Families assisted through development subsidies (and, as noted, through PBRA) receive help to rent a particular unit but usually have to give up their subsidy if they later need to move elsewhere — to be close to a job opportunity, to a relative who can act as a caregiver, or to a school for their child, for example. In contrast, subsidies like the mortgage interest deduction help higher-income households purchase homes where they choose. This contrast has serious implications for racial equity, since most of the benefit from the mortgage interest deduction goes to white households, while most low-income renters who struggle to afford housing are people of color.[15] Housing Choice Vouchers help low-income households rent units in the communities of their choice, but because of limited funding, only a small share of low-income households have gotten help expanding their housing choices through the program.

Compounding this risk from limiting choice is the nation’s long history of discriminatory housing policies, which have concentrated many affordable housing developments in poorer communities with under-resourced schools and other disadvantages. Addressing this legacy will require major public investments in schools and other services and amenities in those communities, but housing policies should also give families with low incomes greater choice about where they live. Policymakers should locate new affordable housing developments in a broader range of neighborhoods, but it not clear that future development efforts will overcome the public resistance that has long blocked affordable housing development in many neighborhoods, especially those with higher-income or predominantly white populations.[16] The recovery bill’s voucher expansion, particularly because it is accompanied by a major investment in mobility services, offers a proven, evidence-based way to ensure that more people with low incomes can live in a neighborhood of their choice.

It is important to note that the recovery bill’s estimated 750,000 new vouchers could be put to use irrespective of the new units that would be built over time with the bill’s supply investments. The voucher program uses virtually every dollar of funding it receives, so the number of families it helps is limited by inadequate funding, not by a shortage of units.[17]

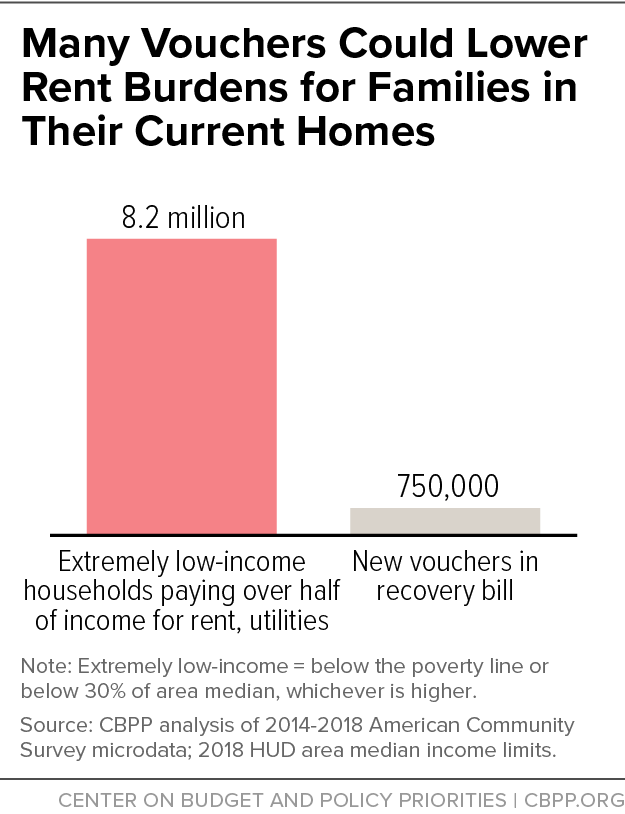

Most households that receive a voucher (two-thirds, in one study) already rent a housing unit, so their vouchers do not add to the number of units demanded in the market.[18] Typically, these households paid very high shares of their income for rent before receiving the voucher, and many simply use the voucher to help them afford their current unit without diverting resources from other basic needs. (The voucher also helps protect them from eviction if their earnings drop or they face unexpected expenses.) More than 8 million extremely low-income households have a home but spend more than half their income to rent it, so 750,000 vouchers could be absorbed many times over simply by helping those households. (See Figure 4.)

The new vouchers would also help people who don’t now have their own unit, such as those living in a shelter or on the streets or who are doubled up with another family. But rental markets could absorb many such households just as they absorb other new renters, such as young adults leaving their parents’ homes or workers relocating to pursue a job opportunity. Rental markets in much of the nation have sizeable numbers of vacant units,[19] and even relatively tight markets could likely absorb the vouchers funded in the recovery bill because the number of units needed would be low compared to the overall housing stock. Many housing agencies in tight markets have routinely used all of the voucher funds they have received in the past.[20]

The bill would fund 150,000 added vouchers a year over five years. If one-third of those voucher holders need a new unit, that would amount to 50,000 units a year, which is less than 2 percent of the units that are vacant and available for rent today and just 0.1 percent of the nation’s total number of rental units.

To be sure, housing supply investments would broaden the range of units available to voucher holders (especially in communities with tight rental markets) and have other important benefits, even if they are not essential to put the new vouchers to use. For this reason, while lawmakers should place the highest priority on the bill’s voucher expansion, the best approach would be for the recovery bill to provide robust funding both for vouchers and other rental assistance and for subsidies to build and renovate affordable housing.

| APPENDIX TABLE 1 |

| Estimated Number of Households and People Assisted Through Recovery Bill’s Housing Voucher Expansion, by State |

| State |

Households |

People |

Female |

Children (Under 18) |

People With Disabilities |

Seniors (62 and older) |

| Alabama |

12,000 |

26,000 |

16,000 |

12,000 |

4,000 |

1,000 |

| Alaska |

1,000 |

2,000 |

1,000 |

1,000 |

1,000 |

N/A |

| Arizona |

14,000 |

34,000 |

20,000 |

15,000 |

6,000 |

3,000 |

| Arkansas |

7,000 |

15,000 |

9,000 |

7,000 |

3,000 |

1,000 |

| California |

103,000 |

259,000 |

150,000 |

87,000 |

55,000 |

43,000 |

| Colorado |

11,000 |

23,000 |

13,000 |

9,000 |

5,000 |

2,000 |

| Connecticut |

9,000 |

18,000 |

11,000 |

6,000 |

4,000 |

2,000 |

| Delaware |

2,000 |

4,000 |

2,000 |

2,000 |

1,000 |

N/A |

| District of Columbia |

3,000 |

6,000 |

4,000 |

2,000 |

1,000 |

1,000 |

| Florida |

43,000 |

98,000 |

59,000 |

40,000 |

18,000 |

11,000 |

| Georgia |

24,000 |

57,000 |

35,000 |

26,000 |

8,000 |

4,000 |

| Hawai’i |

3,000 |

6,000 |

4,000 |

2,000 |

1,000 |

1,000 |

| Idaho |

3,000 |

6,000 |

4,000 |

3,000 |

1,000 |

1,000 |

| Illinois |

31,000 |

67,000 |

41,000 |

26,000 |

12,000 |

7,000 |

| Indiana |

15,000 |

32,000 |

19,000 |

14,000 |

6,000 |

2,000 |

| Iowa |

6,000 |

12,000 |

7,000 |

4,000 |

2,000 |

1,000 |

| Kansas |

6,000 |

12,000 |

7,000 |

5,000 |

3,000 |

1,000 |

| Kentucky |

10,000 |

24,000 |

14,000 |

10,000 |

5,000 |

1,000 |

| Louisiana |

12,000 |

28,000 |

17,000 |

13,000 |

5,000 |

2,000 |

| Maine |

2,000 |

4,000 |

3,000 |

2,000 |

1,000 |

1,000 |

| Maryland |

12,000 |

27,000 |

16,000 |

10,000 |

6,000 |

3,000 |

| Massachusetts |

17,000 |

34,000 |

21,000 |

11,000 |

9,000 |

5,000 |

| Michigan |

21,000 |

47,000 |

28,000 |

19,000 |

10,000 |

3,000 |

| Minnesota |

10,000 |

19,000 |

11,000 |

8,000 |

4,000 |

2,000 |

| Mississippi |

7,000 |

18,000 |

11,000 |

9,000 |

3,000 |

1,000 |

| Missouri |

13,000 |

28,000 |

17,000 |

12,000 |

5,000 |

2,000 |

| Montana |

2,000 |

4,000 |

2,000 |

1,000 |

1,000 |

N/A |

| Nebraska |

4,000 |

8,000 |

5,000 |

3,000 |

1,000 |

1,000 |

| Nevada |

7,000 |

15,000 |

9,000 |

6,000 |

3,000 |

1,000 |

| New Hampshire |

2,000 |

4,000 |

2,000 |

1,000 |

1,000 |

1,000 |

| New Jersey |

21,000 |

47,000 |

29,000 |

17,000 |

9,000 |

7,000 |

| New Mexico |

5,000 |

10,000 |

6,000 |

4,000 |

2,000 |

1,000 |

| New York |

69,000 |

151,000 |

90,000 |

52,000 |

34,000 |

24,000 |

| North Carolina |

23,000 |

52,000 |

32,000 |

22,000 |

9,000 |

4,000 |

| North Dakota |

2,000 |

3,000 |

2,000 |

1,000 |

1,000 |

N/A |

| Ohio |

29,000 |

61,000 |

36,000 |

26,000 |

12,000 |

4,000 |

| Oklahoma |

8,000 |

18,000 |

11,000 |

8,000 |

3,000 |

1,000 |

| Oregon |

9,000 |

19,000 |

10,000 |

7,000 |

5,000 |

2,000 |

| Pennsylvania |

29,000 |

59,000 |

35,000 |

23,000 |

13,000 |

6,000 |

| Puerto Rico |

4,000 |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

| Rhode Island |

3,000 |

6,000 |

4,000 |

2,000 |

1,000 |

1,000 |

| South Carolina |

10,000 |

23,000 |

14,000 |

10,000 |

3,000 |

2,000 |

| South Dakota |

2,000 |

4,000 |

2,000 |

1,000 |

1,000 |

N/A |

| Tennessee |

15,000 |

34,000 |

21,000 |

16,000 |

6,000 |

2,000 |

| Texas |

57,000 |

140,000 |

84,000 |

64,000 |

22,000 |

11,000 |

| Utah |

4,000 |

10,000 |

5,000 |

4,000 |

2,000 |

1,000 |

| Vermont |

1,000 |

2,000 |

1,000 |

1,000 |

1,000 |

N/A |

| Virginia |

16,000 |

36,000 |

22,000 |

15,000 |

7,000 |

3,000 |

| Washington |

15,000 |

31,000 |

18,000 |

11,000 |

8,000 |

4,000 |

| West Virginia |

4,000 |

8,000 |

5,000 |

3,000 |

2,000 |

N/A |

| Wisconsin |

12,000 |

24,000 |

14,000 |

9,000 |

5,000 |

2,000 |

| Wyoming |

1,000 |

2,000 |

1,000 |

1,000 |

1,000 |

N/A |

| Total U.S. |

750,000 |

1,678,000 |

999,000 |

663,000 |

331,000 |

181,000 |

| APPENDIX TABLE 2 |

| State |

American Indian/

Alaska Native |

Asian/

Pacific Islander |

Black |

Latino |

Multi-

racial |

White |

| Alabama |

0% |

1% |

72% |

4% |

1% |

22% |

| Alaska |

19% |

8% |

13% |

11% |

10% |

38% |

| Arizona |

4% |

2% |

20% |

44% |

2% |

28% |

| Arkansas |

0% |

1% |

49% |

6% |

2% |

41% |

| California |

0% |

13% |

22% |

41% |

2% |

22% |

| Colorado |

1% |

3% |

19% |

36% |

2% |

40% |

| Connecticut |

0% |

2% |

28% |

44% |

2% |

24% |

| Delaware |

0% |

2% |

62% |

13% |

2% |

21% |

| District of Columbia |

0% |

2% |

85% |

6% |

1% |

6% |

| Florida |

0% |

1% |

49% |

29% |

1% |

20% |

| Georgia |

0% |

2% |

74% |

8% |

2% |

15% |

| Hawai’i |

0% |

47% |

2% |

18% |

17% |

17% |

| Idaho |

2% |

1% |

4% |

19% |

2% |

73% |

| Illinois |

0% |

3% |

61% |

14% |

2% |

21% |

| Indiana |

0% |

2% |

45% |

7% |

3% |

43% |

| Iowa |

1% |

4% |

26% |

9% |

2% |

58% |

| Kansas |

1% |

3% |

34% |

14% |

4% |

45% |

| Kentucky |

0% |

1% |

31% |

4% |

3% |

60% |

| Louisiana |

0% |

1% |

78% |

4% |

1% |

16% |

| Maine |

1% |

1% |

10% |

3% |

4% |

81% |

| Maryland |

0% |

3% |

65% |

10% |

2% |

20% |

| Massachusetts |

0% |

6% |

20% |

34% |

2% |

38% |

| Michigan |

1% |

2% |

54% |

6% |

3% |

35% |

| Minnesota |

3% |

4% |

46% |

8% |

4% |

35% |

| Mississippi |

0% |

1% |

79% |

2% |

1% |

17% |

| Missouri |

0% |

2% |

49% |

4% |

3% |

42% |

| Montana |

19% |

1% |

2% |

6% |

3% |

69% |

| Nebraska |

2% |

2% |

34% |

14% |

3% |

44% |

| Nevada |

1% |

3% |

43% |

25% |

3% |

25% |

| New Hampshire |

0% |

2% |

5% |

12% |

2% |

79% |

| New Jersey |

0% |

4% |

36% |

34% |

1% |

25% |

| New Mexico |

8% |

1% |

5% |

64% |

1% |

21% |

| New York |

0% |

5% |

28% |

34% |

2% |

30% |

| North Carolina |

1% |

1% |

61% |

9% |

2% |

26% |

| North Dakota |

15% |

3% |

13% |

4% |

3% |

62% |

| Ohio |

0% |

1% |

50% |

6% |

3% |

39% |

| Oklahoma |

7% |

2% |

38% |

10% |

7% |

36% |

| Oregon |

1% |

4% |

11% |

18% |

5% |

60% |

| Pennsylvania |

0% |

3% |

41% |

16% |

2% |

37% |

| Rhode Island |

1% |

3% |

14% |

37% |

2% |

43% |

| South Carolina |

0% |

1% |

71% |

5% |

2% |

21% |

| South Dakota |

33% |

3% |

8% |

7% |

2% |

46% |

| Tennessee |

0% |

1% |

57% |

6% |

2% |

34% |

| Texas |

0% |

2% |

40% |

41% |

1% |

15% |

| Utah |

2% |

6% |

9% |

23% |

2% |

58% |

| Vermont |

1% |

3% |

6% |

2% |

2% |

87% |

| Virginia |

0% |

4% |

55% |

9% |

2% |

29% |

| Washington |

2% |

8% |

19% |

15% |

6% |

49% |

| West Virginia |

0% |

1% |

13% |

1% |

3% |

81% |

| Wisconsin |

1% |

3% |

39% |

11% |

3% |

43% |

| Wyoming |

3% |

1% |

4% |

20% |

3% |

69% |

| Total U.S. |

1% |

4% |

40% |

23% |

2% |

29% |