Federal Policy Changes Can Help More Families with Housing Vouchers Live in Higher-Opportunity Areas

End Notes

[1] CBPP analysis of HUD 2017 administrative data.

[2] Caroline Ratcliffe and Emma Kalish, “Escaping Poverty: Predictors of Persistently Poor Children’s Economic Success,” U.S. Partnership on Mobility from Poverty, May 2017, https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/90321/escaping-poverty.pdf.

[3] Broad-scale economic development and revitalization strategies for disadvantaged neighborhoods (including those, such as HOPE VI, that emphasize revitalizing affordable housing developments have proven costly, often take years to implement, and have yielded mixed results for low-income residents. See Susan J. Popkin and Mary Cunningham, “Has HOPE VI transformed residents’ lives?,” in H.G. Cisneros & L. Engdahl, eds., From Despair to Hope: HOPE VI and the New Promise of Public Housing in America’s Cities, Brookings Institution Press, 2009, pp. 191-204. While we have much to learn about which interventions are effective in transforming poor areas at a substantial scale, researchers have identified several successful examples of such changes (e.g., Tennessee Valley Authority and casino gaming on some American Indian reservations), as well as promising efforts to improve outcomes for families in poor communities by targeting them with intensive services and supports for families (e.g., Harlem Children’s Zone). See Margery Austin Turner et al., “Opportunity Neighborhoods: Building the Foundation for Economic Mobility in America’s Metros,” US Partnership on Mobility from Poverty, February 2018, https://www.mobilitypartnership.org/opportunity-neighborhoods; Laura Tach and Christopher Wimer, “Evaluating Policies to Transform Distressed Urban Neighborhoods,” US Partnership on Mobility from Poverty, October 2017, https://www.mobilitypartnership.org/file/1218161/download?token=KviEEtEo; and Patrick Sharkey, “Neighborhoods, Cities, and Economic Mobility,” Russell Sage Foundation Journal of the Social Sciences, Vol. 2, 2016, pp. 159-177, https://www.rsfjournal.org/doi/full/10.7758/RSF.2016.2.2.07.

[4] Rebecca Casciano and Douglas S. Massey, “Neighborhood Disorder and Individual Economic Self-Sufficiency: New Evidence from a Quasi-experimental Study,” Social Science Research, February 2012, pp 1-18.

[5] Xavier de Souza Briggs, The Geography of Opportunity: Race and Housing Choice in Metropolitan America, Brookings Institution Press, 2005.

[6] For a synthesis of some of this research, see Barbara Sard and Douglas Rice, “Creating Opportunity for Children: How Housing Location Can Make a Difference,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, October 15, 2014, https://www.cbpp.org/research/creating-opportunity-for-children; Patrick Sharkey, Stuck in Place: Urban Neighborhoods and the End of Progress toward Racial Equality, University of Chicago Press, 2013; Sharkey, 2016, op. cit.

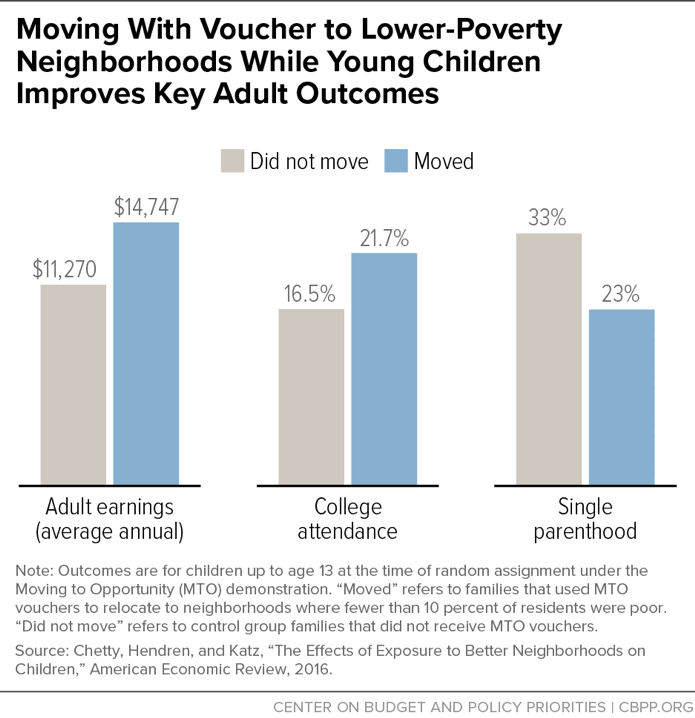

[7] Raj Chetty, Nathaniel Hendren, and Lawrence Katz, “The Effects of Exposure to Better Neighborhoods on Children: New Evidence from the Moving to Opportunity Experiment,” American Economic Review, April 2016, pp. 855-902. (This study was first released in 2015, see http://www.equality-of-opportunity.org/images/mto_paper.pdf). The results of this study are broadly consistent with the impressive outcomes found in the quasi-experimental Gautreaux studies, which tracked the outcomes of low-income families who used housing vouchers to move from segregated public housing developments in Chicago to middle-class, mostly-white suburbs. See also James E. Rosenbaum, “Changing the Geography of Opportunity by Expanding Residential Choice: Lessons from the Gautreaux Program,” Housing Policy Debate, 1995, pp. 231-269; Stefanie DeLuca and Elizabeth Dayton, “Switching Social Contexts: The Effects of Housing Mobility and School Choice Programs on Youth Outcomes,” Annual Review of Sociology, August 2009, pp. 457–491.

[8] Raj Chetty and Nathaniel Hendren, “The Effects of Neighborhoods on Intergenerational Mobility I: Childhood Exposure Effects and II: County-Level Estimates,” Quarterly Journal of Economics (August 2018, a version of which was released in 2015) tracked more than 7 million lower-income families who moved across county lines or “commuting zones,” comparing outcomes of children who moved to better neighborhoods (as measured by the outcomes of the children already living there) to those who did not. Consistent with the findings of their MTO analysis, the researchers found greater college attendance, less teenage pregnancy, and higher incomes as young adults for the children in families that moved to better areas. The longer the children lived in better areas, the stronger were these positive effects. The five location characteristics most strongly correlated with low-income children’s long-term outcomes were segregation by race and income (including concentration of poverty), income inequality, school quality, preponderance of two-parent families, and rate of violent crime.

[9] Jens Ludwig et al, “Long-Term Neighborhood Effects on Low-Income Families: Evidence from Moving to Opportunity,” American Economic Review, May 2013, pp. 226-231.

[10] Several MTO studies have found differences in mental health outcomes for boys and girls in families that used vouchers to relocate to lower-poverty areas. These studies generally find reduced risks of depression and other mental health improvements among girls, but several found worse mental health outcomes among boys. The latter findings are not well understood. One potential factor identified by researchers is that neighborhood changes may weaken boys’ relationships with fathers who remain behind. Racial bias among white residents of low-poverty neighborhoods may also have a greater impact on black boys than girls. For discussion of these findings, see Sard and Rice (2014), and Raj Chetty, et al., “Race and Economic Opportunity in the United States: An Intergenerational Perspective,” March 2018, http://www.equality-of-opportunity.org/assets/documents/race_paper.pdf. From a policy perspective, it is important to keep in mind that the share of boys experiencing worse mental health was small (fewer than 1 in 20), and despite these negative impacts, boys overall experienced positive long-term gains (e.g., in college attendance and earnings) identified by Chetty and his colleagues. Still, the mental health outcomes for boys are cause for concern and suggest that counseling and other forms of support for parents and children aimed at easing their transition to new neighborhoods are important. These outcomes also reinforce the importance of family choice of housing and location as a key principle of housing policy: family needs may be complex, and parents are ultimately the best judge of what type of housing and neighborhood best suits their family’s needs.

[11] Schwartz’s study took advantage of a natural experiment made possible by the county’s housing policies. Applicants for public housing assistance were randomly assigned to public housing developments across the county. Because of the county’s zoning policies, most of these developments are in low-poverty neighborhoods (with poverty rates of less than 10 percent), while the others are in neighborhoods with moderate or high poverty rates (up to 32 percent). This enabled Schwartz to compare educational outcomes for students living in neighborhoods and attending schools that differed significantly with respect to poverty and related characteristics.

[12] Heather Schwartz, “Housing policy is school policy: Economically integrative housing promotes academic success in Montgomery County, Maryland,” in R.D. Kahlenberg, ed., The Future of School Integration, Century Foundation, 2012. A study of families participating in the Baltimore Housing Mobility Program also found promising gains in reading and math test scores after five years for children in families that used vouchers to move to low-poverty areas, although the study did not have a control group. See Stefanie DeLuca et al., The Power of Place: How Housing Policy Can Boost Educational Opportunity, Abell Foundation, 2016, https://abell.org/sites/default/files/files/ed-power-place31516.pdf.

[13] For references, see Sard and Rice, 2014.

[14] Racism and discriminatory public policies have played a central role in the creation and persistence of neighborhoods of extreme poverty, which are home primarily to people of color, particularly African Americans. (These factors also contributed to the creation and persistence of high-opportunity neighborhoods, which are predominantly white.) See, for instance, Richard Rothstein, The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America, Liveright, 2017, and Sharkey, 2013, op. cit. For this reason, it is important to recognize that many of the characteristics of extreme-poverty neighborhoods that harm children’s health and chances of success are entangled with the forces of racism.

[15] Robert J. Sampson, Patrick Sharkey, and Stephen W. Raudenbusch, “Durable Effects of Concentrated Disadvantage on Verbal Ability Among African-American Children,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, January 2008, pp. 845-852. Building on the work of Sampson and others, Wodtke, Harding, and Elwert also found that sustained exposure to neighborhoods of concentrated disadvantage had a long-term impact on children’s educational achievement. Analyzing data, including neighborhood changes, for more than 4,000 students from across the country over a 17-year period, they found that high-school graduation rates were 20 percentage points lower for black children with the greatest exposure to neighborhood disadvantage than for comparable black children with the least exposure. See Geoffrey T. Wodtke, David J. Harding, and Felix Elwert, “Neighborhood effects in temporal perspective: The Impact of Long-Term Exposure to Concentrated Disadvantage on High School Graduation,” American Sociological Review, September 2011, pp. 713–736.

[16] Patrick T. Sharkey et al., “The Effect of Local Violence on Children’s Attention and Impulse Control,” American Journal of Public Health, December 2012, pp. 2287-2293. Researchers also found elevated levels of stress among the parents, which suggests that parental stress may be a causal pathway by which violence influences children’s performance. (This hypothesis is consistent with the research on toxic stress discussed below.)

[17] Patrick Sharkey et al., “High Stakes in the Classroom, High Stakes on the Street: The Effects of Community Violence on Students’ Standardized Test Performance,” Sociological Science, May 2014, pp. 199-220.

[18] Patrick Sharkey and Gerard Torrats-Espinosa, “The effect of violent crime on economic mobility,” Journal of Urban Economics, 2017, pp. 22-33. This study builds on the longitudinal data on children’s locations and incomes that Chetty and his colleagues released in 2015 (and published in 2018). Chetty and Hendren (2018) also found strong correlations between local violent crime rates and children’s later incomes as young adults.

[19] National Scientific Council on the Developing Child (NSCDC), “Excessive Stress Disrupts the Architecture of the Developing Brain: Working Paper No. 3,” Harvard University, 2014, https://developingchild.harvard.edu/resources/wp3; NSCDC, “Persistent Fear and Anxiety Can Affect Young Children’s Learning and Development: Working Paper No. 9, Harvard University, 2010, https://developingchild.harvard.edu/resources/persistent-fear-and-anxiety-can-affect-young-childrens-learning-and-development; Jack Shonkoff et al., “Neuroscience, molecular biology, and the childhood roots of health disparities: building a new framework for health promotion and disease prevention,” JAMA, June 2009, pp. 2252-2259, http://www.brooklyn.cuny.edu/pub/departments/childrensstudies/conference/pdf/Shonkoff-Boyce-McEwen_JAMA.pdf; Shonkoff et al., “The lifelong effects of early childhood adversity and toxic stress,” PediatricsMonth, 2012, pp. 232-246, http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/pediatrics/129/1/e232.full.pdf.

[20] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, “Child maltreatment: risk and protective factors,” April 10, 2018, https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/childabuseandneglect/riskprotectivefactors.html. Nurturing support from parents and other adults can mitigate the effects of stress on children. Yet poor parents living in high-poverty neighborhoods experience hardships, stresses, and stress-related problems — such as depression — to a degree that can hinder their ability to provide nurturing support for their children (and may engender or exacerbate negative outcomes among children). NSCDC, “Maternal Depression Can Undermine the Development of Young Children: Working Paper No. 8,” Harvard University, 2009, https://developingchild.harvard.edu/resources/maternal-depression-can-undermine-the-development-of-young-children/.

[21] American Academy of Pediatrics, “Early childhood adversity, toxic stress and the role of the pediatrician: Translating developmental science into lifelong health,” January 2012, http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/129/1/e224.

[22] Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, “Policy Basics: The Housing Choice Voucher Program,” updated May 3, 2017, https://www.cbpp.org/research/housing/policy-basics-the-housing-choice-voucher-program.

[23] CBPP analysis of Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) 2017 administrative data. See Appendix Table A-1.

[24] Will Fischer, “Research Shows Housing Vouchers Reduce Hardship and Provide Platform for Long-Term Gains Among Children,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, October 7, 2015, https://www.cbpp.org/files/3-10-14hous.pdf; Barbara Sard, Mary Cunningham, and Robert Greenstein, “Helping Young Children Move Out of Poverty by Creating a New Type of Rental Voucher,” US Partnership on Mobility from Poverty, February 8, 2018, https://www.mobilitypartnership.org/helping-young-children-move-out-poverty-creating-new-type-rental-voucher.

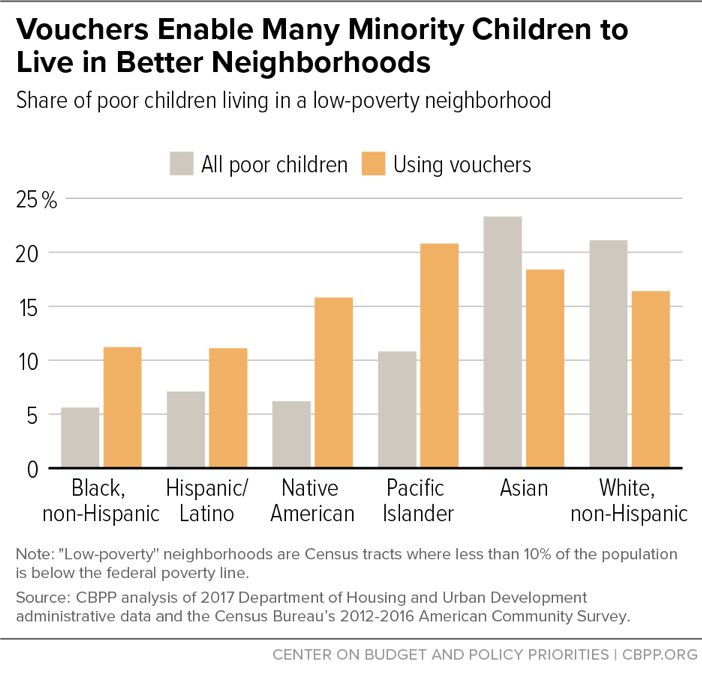

[25] In 2017, the median poverty rate of communities where poor children using vouchers lived was 24.2 percent, slightly higher than the comparable rate for all poor children of 22.9 percent, according to CBPP analysis of the 2012-2016 American Community Survey. (In contrast, the median neighborhood poverty rate for all children is 12.5 percent.) Among poor children using vouchers, 12.4 percent lived in low-poverty neighborhoods (poverty rate of less than 10 percent), compared with 11.9 percent of all poor children. See Appendix Tables A-4 and A-5. The racial and ethnic composition of these two groups, however, differ significantly. For example, poor non-Hispanic white, Asian, and Pacific Islander children — who typically live in lower-poverty neighborhoods than other poor children — make up 34.2 percent of all poor children but only 21.2 percent of poor children using vouchers.

[26] In 2017, 13.6 percent of families with children using vouchers lived in low-poverty neighborhoods, compared to 3.9 percent of those in public housing and 6.4 percent of those in privately owned units with project-based rental assistance. Also, families using vouchers were substantially less likely to live in extreme-poverty neighborhoods compared to families in public housing or project-based rental assistance: 13.8 percent of families using Housing Choice Vouchers lived in extreme-poverty neighborhoods, whereas 36.6 percent of family-occupied public housing units and 25.3 percent of family-occupied, privately owned units with project-based assistance were located in extreme-poverty neighborhoods. See Appendix Table A-1.

[27] See Appendix Tables A-3, A-4, and A-5.

[28] See Appendix Tables A-4 and A-5. There is little difference between the share of all poor Hispanic children who live in extremely poor neighborhoods and the share of poor Hispanic children with vouchers who live in these neighborhoods: 15.9 percent of the former live in neighborhoods with a poverty rate of 40 percent or more, compared with 15.6 percent of the latter.

[29] A third of children with vouchers (33.8 percent) live in high-poverty or extreme-poverty neighborhoods, with a poverty rate of 30 percent or more. See Appendix Table A-2.

[30] For example, in St. Louis, 64 percent of families with vouchers offered the option of receiving services from the housing mobility program expressed interest. A nonprofit, Ascend STL Inc., operates the mobility program in partnership with the St. Louis City and County Housing Authorities. Ascend STL Inc., “Mobility Connection Year End Report, 2017,” https://www.ascendstl.org/reports. Housing mobility program administrators in Chicago and Dallas also report strong interest in their voluntary programs, where recruitment generally occurs at the voucher briefing. Jennifer Darrah and Stefanie DeLuca, “Living Here has Changed My Whole Perspective”: How Escaping Inner‐City Poverty Shapes Neighborhood and Housing Choice,” Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, March 2014, pp. 350-384.

[31] Mary Cunningham, et al., “A Pilot Study of Landlord Acceptance of Housing Choice Vouchers: Executive Summary,” HUD, August 2018, https://www.huduser.gov/portal//portal/sites/default/files/pdf/ExecSumm-Landlord-Acceptance-of-Housing-Choice-Vouchers.pdf; Stefanie DeLuca, Philip M. Garboden, and Peter Rosenblatt, “Segregating Shelter: How Housing Policies Shape the Residential Locations of Low-Income Minority Families,” ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, April 2013, pp. 268-299.

[32] Ibid.

[33] HUD rules require agencies to provide information to families when they first receive a voucher about their choices of where to live, and to explain the advantages of moving to an area that does not have a high concentration of poor families. See 24 C.F.R. §982.301. But agencies aren’t required to provide actual assistance to families to find a suitable unit, though HUD’s Housing Choice Voucher Program Guidebook includes some reasons why agencies may find it in their interest to do so. HUD Handbook 7420.10G, chapters 2-9.

[34] HUD measures the performance of agencies in administering the HCV program through the Section 8 Management Assistance Program, known as SEMAP. As discussed below, only a very small share of the points available under SEMAP relate to housing location, and the measures are weakly defined. See below regarding agencies’ duties to further fair housing.

[35] Kirk McClure, “Which Metropolitan Areas Work Best for Poverty Deconcentration with Housing Choice Vouchers,” Cityscape (2013), pp. 209-236.

[36] Alicia Mazzara and Brian Knudsen, “Where Families with Children Use Housing Vouchers: A Comparative Look at the 50 Largest Metropolitan Areas,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, forthcoming.

[37] Mobility Works and Poverty & Race Research Action Council, “Housing Mobility Programs in the United States,” forthcoming September 2018.

[38] Some of these programs are new. For example, the Seattle and King County Housing Authorities began implementing a rigorous randomized control trial in the fall of 2017 to determine what types of interventions are most cost effective in helping voucher holders access low-poverty areas. (See https://www.seattlehousing.org/creating-moves-to-opportunity-seattle-king-county-pilot-project-fact-sheet.) There are three large scale housing mobility programs, in Dallas, Chicago, and Baltimore. Each began as the result of fair housing litigation, and each has reported significant success in moving substantial number of families to much lower-poverty, predominantly non-minority communities. For example, the Baltimore program reports that for families that moved using a voucher for the first time in 2010 or later, the average pre-move poverty rate was 28.4 percent, while the average post-move poverty rate was 6.9 percent. The program has strong retention results as well: as of June 2018, 70 percent of all families in the program remain in opportunity areas and the average neighborhood poverty rate is 10.6 percent. (BRHP administrative data obtained August 2018.) For more information on these three programs, see Barbara Sard and Douglas Rice, “Realizing the Housing Voucher Program’s Potential to Enable Families to Move to Better Neighborhoods,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, January 12, 2016, https://www.cbpp.org/research/housing/realizing-the-housing-voucher-programs-potential-to-enable-families-to-move-to. Other agencies have self-funded mobility initiatives through administrative fees, funds earned from other activities such as developer fees, funds awarded through litigation, and funds made possible by the flexibility to reallocate resources for agencies participating in the Moving to Work demonstration. HUD has also made at least two small awards of discretionary administrative fees for regional mobility initiatives.

[39] A HUD-sponsored study found that in 2013–2014, only about half of the sampled housing agencies devoted any staff time to expanding housing opportunities for families, and none deployed significant staff resources. Jennifer Turnham et al., “Housing Choice Voucher Program: Administrative Fee Study,” Abt Associates, August 2015, https://www.huduser.gov/portal/publications/pdf/AdminFeeStudy_2015.pdf.

[40] The Mobility Works consortium — a group of mobility practitioners, researchers, and policy experts — has been in contact with about a dozen public housing agencies across the country that are interested in developing voucher mobility programs. Some of these emerging programs are underway, but some are not yet serving families. For more information see: www.housingmobility.org.

[41] Speaking on the House floor, Rep. Duffy said: “We know that low-income children whose families move to areas of lower poverty have higher earnings as adults. We must eliminate the cycle of poverty that keeps generations of families living within the same area with a limited amount of opportunity. Helping people move to better opportunities will increase the chances for them to achieve academic success and reduce intergenerational poverty.” Rep. Cleaver echoed those remarks and added: “This bill should pass. . . . All you have to do is read the Harvard research project from Raj Chetty, Nathaniel Hendren, and Lawrence Katz, which spoke about the improved opportunities for children based on their location. Higher opportunity neighborhoods offer just about everything that we would want a child to have growing up in this country.” See 164 Cong. Rec. H6010, daily ed., July 10, 2018, https://www.congress.gov/congressional-record/2018/07/10/house-section/article/H6010-1.

[42] Alicia Mazzara, Barbara Sard, and Douglas Rice, “Rental Assistance to Families with Children at Lowest Point in Decade,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, October 18, 2016, https://www.cbpp.org/research/housing/rental-assistance-to-families-with-children-at-lowest-point-in-decade.

[43] Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, “Proposed Housing Mobility Demonstration Would Improve Families’ Access to High-Opportunity Areas,” July 18, 2018, https://www.cbpp.org/sites/default/files/atoms/files/5-31-18hous_0.pdf.

[44] The 2019 funding bill for HUD that the Senate approved in August 2018 doesn’t include funds for a voucher mobility demonstration. Senators Todd Young (R-IN) and Chris Van Hollen (D-MD) have introduced a bill, S. 2945, to authorize the demonstration, as the House-passed bill (H.R. 5793) would do.

[45] Sard, Cunningham, Greenstein, 2018. The US Partnership on Mobility from Poverty recommends creating an additional 500,000 housing vouchers for families with children, phased in over five years. The vouchers would be targeted on low-income, high-need families with young children and would include funding for services to help families move out of poverty, including mobility counseling and home visiting.

[46] Although HUD convened a group of housing mobility practitioners, researchers, and agencies in early 2016 that many attendees found productive (see https://www.hud.gov/program_offices/public_indian_housing/programs/hcv/mobilityresources), much more could be done to share information and recommended policy changes to promote better locational outcomes for voucher holders.

[47] Agency fees are primarily based on the number of vouchers in use. Leasing units in high-opportunity areas typically takes longer than leasing in neighborhoods where vouchers are commonly accepted. Cunningham, et al., 2018. A fee incentive would help balance agencies’ current financial interest in having families locate units as quickly as possible.

[48] HUD, Housing Choice Voucher Program – New Administrative Fee Formula: Proposed Rule, 81 FR 44099, July 6, 2016; Turnham et al. As noted above, this study found that agencies spent no significant time on landlord outreach or other mobility services, and thus didn’t incorporate the costs of such services in its proposed new fee formula.

[49] The Trump Administration’s most recent regulatory agenda does not include action on this proposal. See Office of Management and Budget, Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs, Agency Rule List – Spring 2018, Department of Housing and Urban Development, www.reginfo.gov.

[50] HUD has authority under its current rule (24 C.F.R. §982.152(a)(iii)(C)) to provide supplemental fees for “extraordinary costs,” which HUD uses to provide a $200 bonus to a housing agency for each family that buys a home while participating in the HCV program.

[51] Under SEMAP, only five out of the 135 points that agencies in metropolitan areas are eligible to receive concern adoption and implementation of policies to “expand housing opportunities,” which HUD defines as encouraging participation of landlords located outside areas of poverty or minority concentration and providing information to voucher holders about such opportunities. 24 C.F.R. § 985.3(g). (Metropolitan agencies required to operate a Family Self-Sufficiency program may earn a total of 145 points.) Agencies can earn an additional five points if half or more of HCV families with children live in “low-poverty” census tracts or the share of families living in such areas increases by 2 percent or more. HUD defines “low poverty” for this purpose as a poverty rate of 10 percent or less, or at or below the overall poverty rate in the agency’s primary service area, whichever is higher (see 24 C.F.R. §985.3(h)). As of 2012, only 166 of the 1,403 agencies operating in metropolitan areas claimed these additional five points (CBPP calculation of HUD SEMAP data).

[52] Recent HUD-sponsored research uses a multi-factor measure of opportunity area, which results in an overall composite index. The composite index includes four unique indicators: percent nonpoor, public school quality, employment access, and environmental hazards. Meryl Finkel et al., “Small Area Fair Market Rent Demonstration Evaluation: Interim Report,” prepared for U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, August 2017, https://www.huduser.gov/portal/publications/SAFMR-Interim-Report.html. See also Mazzara and Knudsen, forthcoming.

[53] Philip Garboden et al., “Urban Landlords and the Housing Choice Voucher Program: A Research Report,” HUD, May 2018, https://www.huduser.gov/portal/sites/default/files/pdf/Urban-Landlords-HCV-Program.pdf.

[54] HUD, Affirmatively Furthering Fair Housing Final Rule, 80 Fed. Reg. 42272 (July 16, 2015).

[55] Ibid.

[56] HUD, Affirmatively Furthering Fair Housing: Streamlining and Enhancements, 83 FR 40713 (August 16, 2018).

[57] HUD, Affirmatively Furthering Fair Housing, 83 FR 23927, May 23, 2018; 24 CFR 903.7(o), Civil rights certification.

[58] See Appendix Table A-3.

[59] Rothstein, 2017, op. cit.

[60] Will Fischer, “Trump Administration Blocks Housing Voucher Policy That Would Expand Opportunity and Reduce Costs,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, September 7, 2017, https://www.cbpp.org/research/housing/trump-administration-blocks-housing-voucher-policy-that-would-expand-opportunity.

[61] Sensibly, the SAFMR rule allows agencies outside of the mandatory areas to use SAFMRs voluntarily. Agencies that are not required to implement SAFMRs should consider whether adopting them would expand voucher holders’ access to low-poverty neighborhoods. Agencies are permitted to set payment standards based on SAFMRs in some or all of the higher-rent zip codes they serve without seeking HUD approval; they may also request HUD approval to fully adopt SAFMRs in place of metro FMRs. Will Fischer, “A Guide to Small Area Fair Market Rents (SAFMR),” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities and Poverty and Race Research Action Council, May 4, 2018, https://www.cbpp.org/research/housing/a-guide-to-small-area-fair-market-rents-safmrs.

[62] HUD, “PIH Notice 2018-01: Guidance on Recent Changes in Fair Market Rent (FMR), Payment Standard, and Rent Reasonableness Requirements in the Housing Choice Voucher Program,” January 17, 2018, https://www.hud.gov/sites/dfiles/PIH/documents/PIH-2018-01.pdf.

[63] HUD, “Implementation of the Federal Fiscal Year (FFY) 2018 Funding Provisions for the Housing Choice Voucher Program,” May 21, 2018, https://www.hud.gov/sites/dfiles/PIH/documents/pih2018-09.pdf. The notice allows agencies to apply for one-time funding for costs associated with adopting SAFMRs.

[64] DeLuca, Garboden, and Rosenblatt (2013); Poverty & Race Research Action Council, “Constraining Choice: The Role of Online Apartment Listing Services in the Housing Choice Voucher Program,” 2015, https://prrac.org/pdf/ConstrainingChoice.pdf; Eva Rosen, “Selection, matching and the rules of the game: Landlords and the geographic sorting of low-income renters,” Joint Center for Housing Studies, 2014, http://www.jchs.harvard.edu/sites/default/files/w14-11_rosen_0.pdf.

[65] 24 C.F.R. § 982.301(b)(11), effective September 21, 2015. 80 Fed. Reg. 50564, 50573, August 20, 2015.

[66] HUD also should evaluate whether listing units in high opportunity areas more prominently will help more families move to low-poverty neighborhoods. In Moving to Opportunity: The Story of an American Experiment to Fight Ghetto Poverty, (Oxford University Press, 2010), p. 233, Xavier de Souza Briggs, Susan J. Popkin, and John Goering emphasize the importance of strategies that would “change the default” of families staying in familiar neighborhoods, citing Richard Thaler and Cass Sunstein, Nudge: Improving decisions about health, wealth and happiness, Yale University Press, 2008.

[67] Some of the listing services focus on the “Section 8 market” while others provide broader listings. HUD initiated a complaint against Facebook alleging that the social media platform allows landlords and home sellers advertising on the site to engage in housing discrimination through targeting tools made available by Facebook. HUD, Housing Discrimination Complaint, Assistant Secretary for Fair Housing & Equal Opportunity v Facebook, August 17, 2018, https://www.hud.gov/sites/dfiles/PIH/documents/HUD_01-18-0323_Complaint.pdf.

[68] DeLuca, Garboden, and Rosenblatt, 2013, pp. 275-280. In most areas of the country, landlords may legally refuse to accept HCVs unless such a refusal can be proven to be a proxy for discrimination based on race, national origin, disability, or family status that is prohibited by the Fair Housing Act. Poverty & Race Research Action Council (PRRAC), “Expanding Choice: Practical Strategies for Building a Successful Housing Mobility Program: Appendix B: State, Local, and Federal Laws Barring Source-of-Income Discrimination,” June 19, 2018, https://www.prrac.org/pdf/AppendixB.pdf. A new HUD-funded study suggests that state or local laws prohibiting discrimination against voucher holders would increase landlord acceptance of vouchers. Mary Cunningham, et al., 2018, https://www.huduser.gov/portal//portal/sites/default/files/pdf/ExecSumm-Landlord-Acceptance-of-Housing-Choice-Vouchers.pdf.

[69] See 24 C.F.R. §982.303. Extensions are required as a reasonable accommodation to people with disabilities, and when families move to the jurisdiction of another agency (see 24 C.F.R. §982.355(c)(13). HUD’s current voucher form, which says, “Insert date sixty days after date,” may mislead agencies about their discretion to provide a longer initial search period.

[70] Barbara Sard and Deborah Thrope, “Consolidating Rental Assistance Administration Would Increase Efficiency and Expand Opportunity,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, April 11, 2016, https://www.cbpp.org/research/housing/consolidating-rental-assistance-administration-would-increase-efficiency-and-expand.

[71] For a discussion of the interrelationship between low-income and racially segregated neighborhoods and lower-quality schools in central cities and some older suburbs, see Xavier de Souza Briggs, “More Pluribus, Less Unum? The Changing Geography of Race and Opportunity,” in The Geography of Opportunity: Race and Housing Choice in Metropolitan America, Brookings Institution Press, 2005, pp. 3-87; Philip Tegeler and Michael Hilton, “Disrupting the Reciprocal Relationship Between Housing and School Segregation,” 2017, https://www.prrac.org/pdf/Disrupting_the_Reciprocal_Relationship_JCHS_chapter.pdf.

[72] Consolidation of housing agencies to form a single metro-wide agency could have greater benefits but also faces greater political hurdles; for many agencies, retaining their independent identity is a paramount concern. This makes it more likely that agencies would join a consortium to achieve administrative economies of scale than to formally consolidate with other agencies. Urban policy experts Bruce Katz of the Brookings Institution and Margery Austin Turner of the Urban Institute have issued a paper recommending regional voucher administration; see “Invest but Reform: Streamline Administration of Housing Choice Voucher Program,” Brookings Institution, September 2013, https://www.brookings.edu/research/invest-but-reform-streamline-administration-of-the-housing-choice-voucher-program/.

[73] FSS is a voluntary program that provides case management services to improve participants’ job prospects and earning potential, such as information on available child care, credit and money counseling, and educational or training programs in the community. It also provides escrow accounts into which the agency deposits the increased rent that a family pays as its earnings rise. Families that complete FSS may withdraw funds from these accounts for any purpose; many FSS graduates use their savings to purchase a home. Most of the roughly 75,000 families currently participating in FSS have vouchers. When a voucher family participating in FSS moves to another jurisdiction, they can only continue participating if the receiving agency has an FSS program and an available slot, or if the initial agency is willing to allow the family to continue in its FSS program. If neither option is workable, families must choose between moving to a higher-opportunity neighborhood that may be better for their children but forfeit their escrowed savings or staying in place while continuing working on the FSS contract. HUD could revise its FSS rules to broaden families’ options to remain in FSS regardless of where they move. The Housing Choice Voucher Mobility Demonstration discussed above would create an incentive for agencies to collaborate to overcome the current barriers to continued FSS participation for families wishing to move to a higher-opportunity community.

[74] According to HUD, in 2014 there were only eight consortia involving 35 agencies that administer the HCV program. HUD, Streamlining Requirements Applicable to Formation of Consortia by Public Housing Agencies, Proposed Rule, 79 Federal Register 40019, July 11, 2014.

[75] Economic Growth, Regulatory Relief and Consumer Protection Act, P.L. 115-174, Sec. 209(c).

[76] Ibid, Sec. 209(e).

[77] The two agencies must split administrative payments and transfer paperwork and funds unless the “receiving” agency “absorbs” the family into its own HCV program by giving the family a voucher it has available instead of serving a family on its waiting list.

[78] Research in Southern California has identified the portability process as a barrier for families and a disincentive for agencies to inform families of their right to move to other jurisdictions. Victoria Basolo, “Local response to federal changes in the housing voucher program: A case study of intraregional cooperation,” Housing Policy Debate, March 2010, pp. 143-168.

[79] One reason “sending” agencies need additional compensation is to encourage them to continually make families aware of their right to use their vouchers in another agency’s jurisdiction and offset their cost of doing so. In the final portability rule, HUD declined to require agencies to remind families about portability after the briefing when they first receive a voucher, stating that “HUD finds this initial briefing to be sufficient.” 80 Fed. Reg. 50570, August 20, 2015. It is not clear on what basis HUD made such a finding. Few families will remember details from the initial briefing that are not of immediate importance to them.

[80] HUD’s proposed rule on administrative fees would provide 100 percent of the fee to the receiving agency, up from 80 percent under the current rule, and allow the initial agency to maintain 20 percent of the fee. HUD, Housing Choice Voucher Program – New Administrative Fee Formula, 81 FR 44099, July 6, 2016.

[81] U.S. Housing Act of 1937, 42 U.S.C. § 1437a(6)(B)(iii) (2006).