Rising rents, housing shortages, and the limited housing choices available to people with low incomes, even if they have rental subsidies, are increasingly recognized as urgent housing policy challenges. While most rental assistance should be provided through subsidies that allow families to choose from a wide range of units, project-based rental assistance — rental subsidies attached to particular properties — is a key tool to address these problems. Long-term property-specific rental assistance can reduce the cost of private market financing, encourage developers to include units affordable to the lowest-income households in their properties, and provide stable affordable homes to the people most in need.

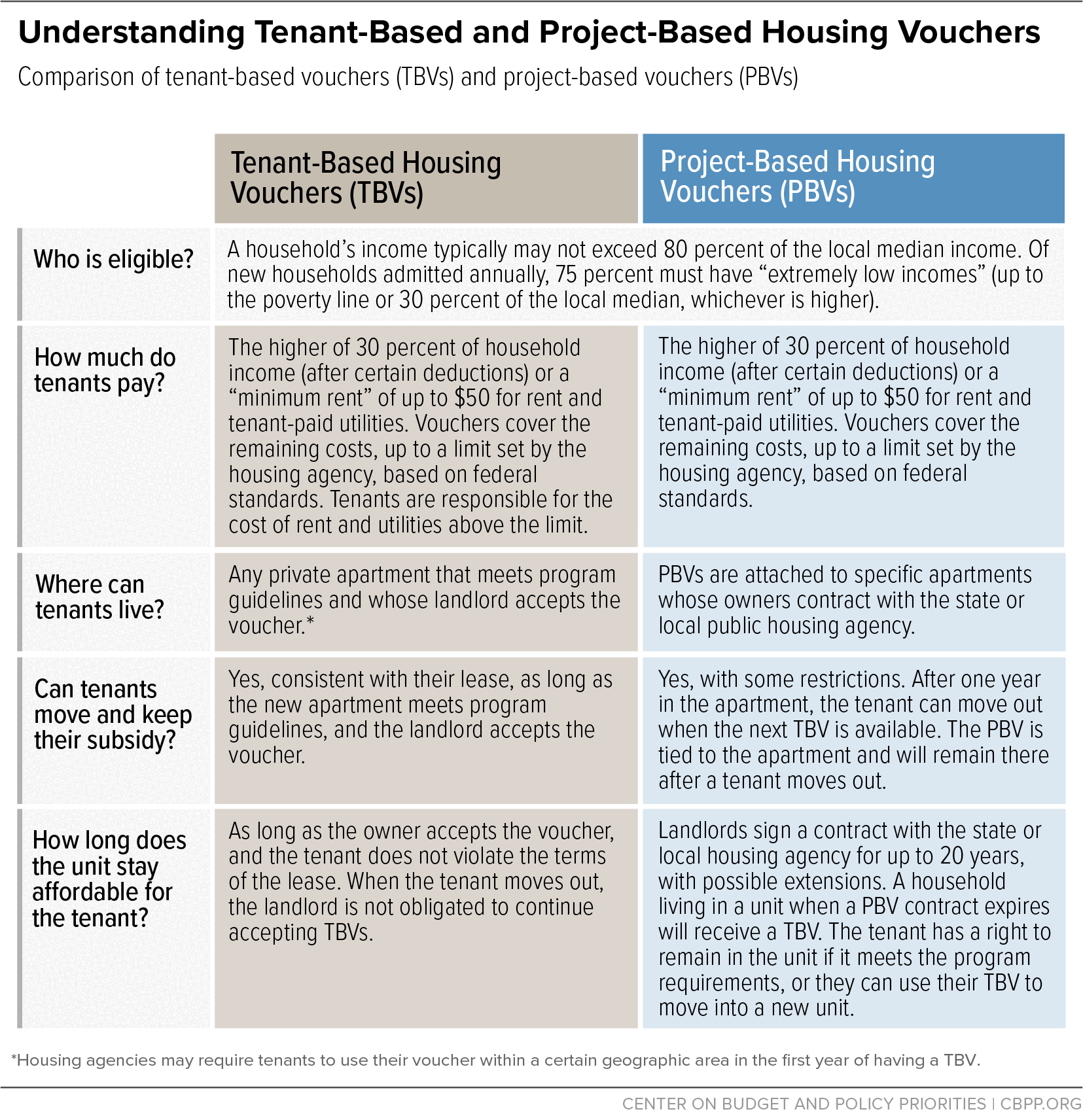

In 2000 Congress approved the redesign of project-based vouchers (PBVs) — an option available as part of the Housing Choice Voucher program that had been rarely used — to encourage new housing development and to increase public housing agencies’ utilization of vouchers in existing housing. While most Housing Choice Vouchers are tenant-based, meaning that people can use them to rent any private apartment that meets program guidelines, PBVs are attached to specific units. (See Figure 1.) Congress’s action was more remarkable because it came not long after Congress had prohibited expanding most of the other project-based rental assistance programs funded by the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD): public housing and most new affordable multifamily development contracts between HUD and private owners.

Bipartisan agreement to enact the revamped PBV program was possible because the changes included innovative policies to promote mixed-income housing and allow families to use tenant-based vouchers to move to housing of their choice, without reducing long-term project-based subsidies on which developers and financers relied. Together these policies aimed to incorporate market-like dynamics to encourage owners to maintain their properties to avoid a high rate of tenant turnover. None of these policies existed in the project-based programs Congress capped or terminated. Subsequently, Congress enacted (also on a bipartisan basis and in periods of Democratic and Republican control of the executive and legislative branches) further policy changes to facilitate the use of PBVs in combination with federal affordable housing tax credits, increase state and local housing agencies’ ability to use PBVs in tight markets and for supportive housing to better address homelessness and assist people with disabilities, and preserve various types of federally funded affordable housing.[2]

The PBV program has become a major component of federal rental assistance policy. At the beginning of 2022, PBV subsidies were under contract to subsidize more than 300,000 housing units. More than 1 out of every 9 households receiving voucher subsidies at the time lived in a PBV unit, reflecting the rapid growth of the program in the prior decade. Over 60 percent of all medium and large public housing agencies, which administer 92 percent of authorized vouchers, operated a PBV program. The PBV program likely will continue to grow and be critical to secure affordable housing opportunities in markets that are challenging for use of tenant-based vouchers and for people who need on-site supportive services to retain their housing, such as some individuals with disabilities or people who are experiencing homelessness, including veterans.

Going forward, policymakers should retain the major changes enacted in the 2000 and later PBV statutory changes. This includes two key policies that distinguish the PBV program from other federal project-based rental assistance programs: requirements for Resident Choice, and for economic integration within properties with PBVs and the neighborhoods where PBVs are located. Together, these policies promote mixed-income properties, locating properties in low-poverty neighborhoods, and residents’ ability to move and retain their assistance, all of which bring market-like discipline to assisted properties by creating incentives for developers and owners to select in-demand locations and to maintain their properties.

In addition, policymakers should maintain a reasonable cap on the share of vouchers that an agency can project-base, as discussed below. This is essential because ensuring that PBV residents have a meaningful right to move with continuing rental assistance to housing of their choice — and that new voucher applicants can receive flexible rental assistance — requires the availability of tenant-based vouchers.

These key features of PBVs should be incorporated in any new investment to expand or preserve properties with project-based rental assistance. HUD also should take steps to ensure that key policies are enforced and work with practitioners, residents, and other stakeholders to learn more about the operation and impact of the program’s features.

It is important to understand the unusual process and key factors that resulted in the 2000 revamp of the PBV program, and the rationale for the major policy changes incorporated in the legislation and subsequent amendments. Understanding the rationale for the continued broad-based support for the revamped PBV program is vital in future consideration of policies for providing project-based rental subsidies.

Project-Based Voucher Program Needed 2000 Revamp

Project-Based Voucher Policy Changes in 2000 Created New Improved Model for Project-Based Rental Assistance

Subsequent Major Changes in PBV Policies Through 2022

Innovative PBV Policies Should Be Maintained and Apply to Any Newly Funded Federal Project-Based Rental Subsidies

Appendices

Bibliography

In 2000 Congress enacted comprehensive legislation that transformed the project-based component of the Housing Choice Voucher (HCV) program.[3] The changes were included as part of the fiscal year 2001 appropriations bill for HUD and other agencies, the last such bill of the Clinton Administration. Only a scant public record exists for the legislation. While it is not unusual for Congress to make amendments to the U.S. Housing Act as part of an appropriations bill, it is rare that such changes occur without a prior Administration proposal or consideration by any congressional committee.

Pre-2000 Rules Limited Use and Effectiveness of Project-Based Voucher Option

Prior to the congressional revision of PBV policy in 2000, public housing agencies (PHAs) had the option to project-base 15 percent of their HUD funding for tenant-based rental assistance, but few made use of it.[4] A variety of reasons contributed to this minimal use.

HUD rules prohibited PHAs from committing rental subsidy funds for more than five years and required PHAs to have guaranteed funding for the duration of the project-based contract at the point of the initial commitment and any renewal.[5]

By 2000 Congress had shifted away from multi-year advance funding to PHAs of new or renewed tenant-based rental assistance, due to PHAs’ accumulation of unspent funds.[6] As a result, PHAs without substantial reserves only had one year’s funding available at a time for each rental certificate. The change in congressional funding practices meant that few PHAs could enter into a project-based contract for more than one year, severely reducing any benefit to the property owner, or rationale for PHAs to undertake the additional upfront administrative work of setting up a project-based voucher program and entering into individual contracts.[7]

Even if, to be consistent with Congress’ changed funding policy, HUD had modified its regulations to allow multiyear project-based voucher contracts subject to annual funding, the program rules were so cumbersome that few PHAs or developers were interested. In order to agree to attach rental subsidies to properties or extend contracts, PHAs needed prior HUD approval before nearly every significant step in the contracting process.

These requirements created delays in the housing development process.[8] In addition, the program lacked financial incentives for developers to make a long-term commitment to accept voucher holders for particular units — unlike the flexibility in the regular tenant-based programs that allowed landlords to decline to renew an expired lease.

Without the flexibility to project-base rental subsidies in existing housing (that is, units that did not need rehabilitation to meet HUD’s quality standards), the option was not useful as a short-term strategy to make it easier to use vouchers in areas where PHAs were not able to use all their funded vouchers. Challenges in using voucher funding were a major concern of policymakers, PHAs, and housing advocates in 2000.[9]

Properties with project-based voucher assistance under pre-2000 policies were similar in key ways to public housing or other multifamily properties with development contracts between HUD and private owners. All units in the properties were likely to have project-based rental assistance, and as a consequence, to be restricted to low-income families. Families who wanted to move out of an assisted unit would likely have to pay market-rate rent due to long waiting lists to receive a tenant-based voucher or to move into another assisted unit. Since few such families could afford market rent, they were likely to tolerate poor conditions in their unit or common areas of the building, or dangerous neighborhood conditions, in order to retain subsidized rent and keep their family stably housed. Even if they left, other families struggling to keep up with rent would want to move in due to the reduced rent. As a result, landlords had an assured rent stream regardless of poor management of the properties, unless PHAs enforced requirements that properties comply with quality standards, which would require extra work for PHAs.

By 2000, many housing policy analysts and practitioners had concluded that rental assistance programs should be designed to promote mixed-income housing rather than fully assisted properties.[10] Critics assumed that mixed-income properties would be better maintained, benefit residents socially and economically, and reduce patterns of racial segregation.[11]

This emerging consensus was among the key reasons that bipartisan support for tenant-based subsidies had grown compared with support for HUD’s “old-style” project-based subsidies like public housing and privately owned fully HUD-assisted multifamily properties.[12] Indeed, by 2000 Congress had prohibited additional subsidized units under either program.[13]

By the latter part of the 1990s, the Clinton Administration was concerned about the worsening shortage of affordable rental units and reduced utilization of funded vouchers. The Republican-controlled Congress shared the latter concern and, to a lesser extent, also wanted to address the underlying problem in some communities of a shortage of rental units.[14] Whether due to adherence to changing views on what types of rental subsidies were best, or beliefs about the importance of families’ surroundings and their ability to access quality education and employment, the Clinton Administration did not propose to make the PBV program more workable as one strategy to address its concerns. Instead, the Administration put forward a proposal for a new type of tenant-based voucher (Housing Production Voucher) that would in theory encourage new production of mixed-income properties in areas with lower rates of poverty (specifically, areas outside of “Qualified Census Tracts” as defined for purposes of the Low Income Housing Tax Credit program[15]) and would provide families as much flexibility to move as they had with regular tenant-based subsidies.

The Clinton Administration’s budget for fiscal year 2001 included a modest proposal for 10,000 new Housing Production Vouchers to address the growing challenges families with vouchers faced in finding units in a tightening rental market, particularly in lower-poverty neighborhoods. (The Clinton Administration [1993-2001] was generally a period of rising incomes, increasing the competition for desirable rental units in many areas.) The new vouchers would have to be used together with Low Income Housing Tax Credits (LIHTCs) or federally insured loans to make up to 25 percent of rental units in newly constructed buildings affordable to extremely low-income families.[16]

Potential allies, however, were skeptical of the proposal. They were concerned that it would be ineffective at increasing production of new affordable units and too limited given the scale of the problem, particularly for the lowest-income renters.[17] The critical weakness of the proposal was that the new vouchers would be required to be used in newly constructed units for only one year. After that initial period, families could take the vouchers to move to other housing; if they did, PHAs would not be required to notify other voucher holders of the vacancy. With no guarantee of an ongoing federal subsidy stream attached to the property, developers would have little incentive to accept the new type of vouchers.[18]

Shortly after the Administration issued its budget proposal in early 2000, the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities (CBPP) proposed an alternative approach: redesign the statutory option to project-base housing vouchers to incorporate key features of the Administration’s proposal and other changes to make project-basing more efficient and attractive for PHAs and developers. Building on the PBV framework would enable PHAs to enter into long-term contracts that provide a secure stream of rental income essential to increase interest among housing developers in the subsidy contracts.

This alternative proposal incorporated two key parts of the Administration’s proposal: flexibility for families to move with continuing rental assistance, but with additional policies that retain the project-based subsidy to house other families (later called the Resident Choice requirement); and encouragement of mixed-income development by restricting the share of units in a property that could have project-based voucher assistance (later known as the Project Cap requirement). It also included a new option for PHAs to project-base vouchers in existing housing as a way to increase their voucher utilization.

This alternative proposal had many of the same goals as the proposal in the Administration’s budget. Both proposals were intended to increase the use of housing vouchers to expand families’ residential choices, particularly in lower-poverty neighborhoods, through receipt of rental assistance. Both were also motivated by the concern that the LIHTC program alone often did not make housing affordable to the lowest-income families and a desire to avoid the deterioration in living conditions that had plagued a large share of “old-style” HUD-assisted properties, whether publicly or privately owned. Finally, both reflected a belief that allowing families to move with continuing rental assistance would have important benefits for families, and that combining the Resident Choice policy with a requirement that only a portion of units in a property receive project-based assistance could help to improve long-term property maintenance.

Beyond the potential housing policy gains from such a hybrid program, for proponents of the housing voucher program it presented an opportunity to increase support for an expansion of vouchers. By 2000, tenant-based rental assistance enjoyed bipartisan support from policymakers and experts. But it was not a priority for the groups with the most power in influencing housing legislation or funding levels — program administrators and the multifamily housing developers and managers who benefited financially from federal housing programs. Establishing a project-based voucher component that owners and developers used would give them a tangible stake in maintaining and expanding funding for housing vouchers generally.

The alternative proposal was intended both to achieve the Administration’s goals and be sufficiently attractive to PHAs and property owners and developers that they would likely use the PBV option at significant scale. However, enacting major changes to the PBV program beyond what was in the budget would require support from the Administration, and backing — or at least not opposition — from influential housing groups.

Within about a month after the President’s budget was issued in early February, key HUD and congressional staff and stakeholder groups had begun to review the proposal circulated by CBPP. Organizations representing the interests of low-income people (National Low Income Housing Coalition, National Housing Law Project), anti-homelessness groups (National Alliance to End Homelessness, Corporation for Supportive Housing), and developers of low-income housing (National Housing Conference) were early supporters.

Some PHA leaders were intrigued about the potential to enact a streamlined, easier-to-administer project-based program that could attract property owners and developers in tight markets, but many were also concerned that a requirement to prioritize available vouchers for families in PBV units who want to move with continued rental assistance (moving vouchers) would add to the delay facing applicants already on waiting lists. In addition, PHA leaders pushed back on the strict limitations on the share of units in a property that could receive new project-based assistance — the Project Cap that the Administration had proposed.

Feedback from stakeholders led to some early modifications to the alternative proposal. The changes would make it optional for PHAs to provide moving vouchers to families in PBV units (unless the subsidies were newly funded under the Administration’s proposal). The revised proposal also allowed PHAs to project-base existing vouchers in all units of a property located in a low-poverty or high job-growth area, and in up to half of the units in a property located outside of such areas (rather than 25 percent of units as the Administration proposed). (See Table 1.)

| TABLE 1 |

|---|

|

| | 1998 Project-Based Voucher Policy | Clinton Administration Housing Production Voucher (HPV) Proposal | Alternative Proposal | Final 2000 Legislation |

|---|

| Resident Choice (right to move with tenant-based voucher) | No | Yes, after one year (family’s voucher no longer restricted to particular property) | Initially for all PBVs, then recommended requiring moving vouchers only if more than 25 percent of units have PBVs | Yes, for all residents of PBV units with next available voucher after one year; PBV remains at property |

| Cap on share of units with PBVs in property | No limit | New HPVs limited to 25 percent of units | No limit for buildings occupied primarily by elderly or disabled people or located in low-poverty or high job growth area; otherwise 50 percent (then 75 percent) cap | 25 percent, except if units house elderly or disabled families or those receiving supportive services, or building has four or fewer units |

| Maximum duration of initial project-based contract | 1-5 years, depending on available funding | 1 year; tenant right to remain for total of 15 years | 10 years subject to annual appropriations | 10 years subject to annual appropriations |

| HUD oversight | HUD prior approval required of new and extended contracts, including site of new construction | State agencies administering Low Income Housing Tax Credits select properties where HPVs to be used; no change in PBV policies | No HUD approval of individual PBV contracts or extensions | No HUD approval required to operate a PBV program, select buildings to receive PBV contracts, or determine the duration of an initial or extended PBV contract |

| Use in existing housing | No; permitted only with use of other funds for rehabilitation or construction | No; HPVs only in new construction with LIHTCs or HUD-insured mortgage | Allowed, consistent with PHA plan | Allowed, consistent with PHA plan |

Neither the House nor the Senate — both controlled by Republicans at the time — included the Administration’s proposal or the alternative in their fiscal year 2001 HUD funding bills. The House-passed bill included funding for about 10,000 new housing vouchers for families living in properties constructed under the LIHTC program, similar to the Administration’s request. But it did not require the vouchers to be project-based or make any changes to PBV program requirements, and did not specify any new policies that would apply to the new vouchers.[19] The Senate bill did not include any funding for new vouchers, although it did propose to allow PHAs to project-base up to 25 percent of their funded vouchers, rather than the 15 percent limit in existing law. This reflected the Appropriations Committee’s belief that HUD should do more to support new housing production, particularly for older adults and people with disabilities.[20]

Given the House and Senate’s rejection of the Administration’s proposal for a modified type of voucher to encourage production of new affordable units — but interest from both the Administration and Congress to adopt some policy changes toward this goal — efforts continued to include statutory changes to the PBV program in the final fiscal year 2001 HUD appropriation bill.

Realizing that Congress was not likely to adopt the budget proposal for Housing Production Vouchers, Michael Deich, the Clinton-appointed Principal Associate Director at the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) responsible for HUD (and many other agencies), was willing to consider the alternative proposal as the basis of a possible compromise. During the summer and early fall of 2000, Deich convened numerous meetings and conference calls with Barbara Sard from CBPP and Steve Redburn, director of OMB’s Housing Branch[21] about the rationale for the changes CBPP proposed in the PBV program and OMB concerns.

Many of the PBV program changes in the alternative proposal — including the flexibility to project-base subsidies in existing housing as a voucher utilization tool — were not controversial. The two major sticking points were the Resident Choice requirement and the Project Cap, for which the alternative proposal included less stringent policies than the Administration’s original proposal in order to gain the support of PHA groups.[22]

In the hope of gaining solid Administration support without losing key allies, CBPP privately sought a middle ground on the two major issues: PHAs would be required to offer families the right to move with the next available voucher in any property where more than 25 percent of units had PBV assistance — except if a project houses older or disabled families, in which case it could be fully assisted and PHAs would not be required to provide moving vouchers. By tying the two most controversial issues together, this proposal aimed to leverage PHA interest in more fully assisted properties to reduce opposition to the Resident Choice requirement.

The final negotiation between the Administration and Congress, however, rejected this compromise position.[23] The final legislation, discussed below, mandated that the Resident Choice requirement apply to all families living in PBV units for more than one year — as the Administration and the alternative had originally proposed — and allowed only narrow exceptions to the 25 percent cap on the share of units in a property that could have project-based assistance. Other policies from the alternative proposal, including some that OMB career staff disagreed with, were included in the final legislation, likely because other Administration officials agreed with the alternative approach. (See Table 1 above.)

Statutory policies on both the Project Cap and the maximum contract term, among other issues, continued to evolve. (The major changes after 2000 are discussed below with additional details in Appendix Table 2.) Despite stakeholders’ objections, however, the right to move from a PBV unit with continued rental assistance has remained unchanged.

For nearly 50 years, from the initial authorization of the public housing program in the U.S. Housing Act of 1937 through the 1980s, Congress provided funding to enable public housing agencies and later, private developers, to build and operate new housing with affordable rents for low-income people. Through these programs, about 3 million units with project-based rental subsidies were built before Congress repealed the authority to continue expansion.[24] These properties were increasingly occupied primarily by households with incomes below the poverty line and were often located in neighborhoods that were economically and racially segregated and received inadequate resources for schools and other public services.[25] To continue receiving rental assistance families generally had to stay where they were due to limited transfer options and long waiting lists for tenant-based vouchers and other assisted properties.

Many reasons contributed to policymakers’ ceasing to fund additional units through the major project-based rental assistance programs and allowing the number of existing units to decline. But they boiled down to a bipartisan, though not unanimous, belief that the programs had failed. Through periods of Democratic and Republican control of the executive and legislative branches, the exception to these trends was bipartisan support for policy changes to the Project-Based Voucher program in 2000, as well as subsequent legislative modifications in 2008 and 2016.

Incorporating Market Discipline and Broader Housing Choices to Make the Project-Based Voucher Program More Effective

Compared with prior federal project-based rental assistance programs, the most innovative changes made by the legislation Congress enacted in 2000 were policies to enhance market-like discipline and to expand families’ housing choices. Two key policy changes — the Resident Choice requirement and Project Cap — aimed to create financial incentives for property developers and owners to locate and sustain housing so that households with incomes around or below the poverty line have more choice of where they want to live without compromising housing quality and neighborhood amenities.

The Project Cap policy — also known as the “income mixing requirement” — requires a majority of units in a property to be rented without project-based rental subsidies. Owners that charge market rents for such unsubsidized units compete with other unsubsidized comparable units in the local market. Owners will generally be better off if they keep their properties in good enough condition that most residents of PBV units and those without rental subsidies choose to stay. High tenant turnover increases owners’ operating costs, due to cleaning and repainting; increases time to select new tenants; and may reduce rent revenue due to unit vacancies.[26]

The 2000 amendments capped at 25 percent the share of units in a property that may have PBV assistance, unless the additional units housed elderly or disabled individuals or families, or other families receiving supportive services.[27] These exceptions were consistent with the dual rationale for the Project Cap policy: bringing market-like discipline to the property and the assumed social benefits for adults expected to work and for children, of living in properties that also had moderate- or higher-income residents. (See footnote 11 for discussion of questions raised about this assumption by later research.) The final legislation did not vary the Project Cap based on the size or location of the property. Subsequent amendments, discussed below, modified the Project Cap policy significantly.

Resident Choice Requirement and Other Policies to Expand Housing Choices

The Resident Choice policy requires PHAs to provide the next available housing voucher to residents of PBV units who wish to move out of the property after one year.[28] By relying on turnover vouchers no longer in use as families leave the program — or newly funded vouchers — for moving vouchers, the policy makes it feasible, without additional funding, to retain the number of units under contract between PHAs and owners to provide project-based rental assistance. This reliable subsidy stream is critical to convincing owners to accept PBV contracts; lenders and other underwriters can also rely on it to facilitate purchase of a property, rehabilitation, or new construction. Many PBV residents are also interested in the opportunities to move to a different unit or neighborhood without losing rental assistance that this requirement provides.[29]

In addition to their flexibility, moving vouchers enable families to adjust the location or size of their residence to changing circumstances or goals without sacrificing the rental subsidy they need. This policy aims to encourage PHAs to select only desirable properties to receive PBV contracts. Otherwise, many tenants living in unsafe areas or locations without access to transportation, jobs, or services will opt to move, reducing the number of regular housing vouchers available to unassisted families on the voucher waiting list. Like the Project Cap, the Resident Choice policy creates an incentive for owners to keep their properties well-maintained.

But many housing practitioners questioned the importance of the ability to move with continued rental assistance and were confused by it. This was in part because they did not believe that there were significant design drawbacks to HUD’s prior project-based rental assistance policies. By combining a tenant-based subsidy option with project-based rental assistance, the policy also crossed what had historically been a clear line between project-based and tenant-based assistance. In addition, many housing practitioners feared that the policy would undermine the stability and economic viability of properties in neighborhoods with high crime rates, low-performing schools, or other disadvantages, leading to the further decline of these neighborhoods.

These fears generally have not been realized. The idea that families’ choices of where they want to live should prevail over government choices of which properties to subsidize has increasingly been accepted as central to housing policy. The most salient example of this policy shift is congressional support for incorporating a “choice mobility” requirement in the Rental Assistance Demonstration, a major initiative enacted in 2011 that allows public housing and privately owned properties to shift to a Section 8 project-based funding stream. This requirement only slightly modifies the PBV Resident Choice requirement.[30]

Moreover, the PBV Resident Choice requirement is a vital tool for the efficient use of limited supportive housing resources for people such as formerly homeless individuals who, after an initial period, no longer need the intensive services that supportive housing provides. Providing individuals who no longer need or want to live in a supportive housing property with the choice to move out with tenant-based assistance frees up scarce units for people who can benefit more from the services the property makes available.[31]

In addition to the Resident Choice requirement, the 2000 amendments included two other policy changes to expand families’ housing choices. First, Congress required that a PHA could only approve a PBV contract if it is consistent with the goal of “deconcentrating poverty and expanding housing and economic opportunities.”[32] This policy has the potential to increase the availability of affordable rental units in lower-poverty areas and communities with better public services such as schools, transportation, and recreation areas. Typically, affordable rental units are scarce in such neighborhoods and owners may be unwilling to rent to voucher holders. Unfortunately, HUD does not require PHAs to report data on the location of units with PBV contracts, so it is not possible to assess systemically whether PHAs are complying with HUD’s regulation, or whether the criteria in the regulation are well designed to increase access to opportunity and to housing outside high-poverty areas in practice.[33]

Second, the 2000 amendments included a rent incentive for developers of properties using Low Income Housing Tax Credits to choose locations in lower-poverty neighborhoods and set aside some units in the properties for voucher holders (similar to the Clinton Administration’s original proposal discussed earlier). If units receiving LIHTCs are located in lower-poverty communities,[34] the rent level subsidized by project-based vouchers may exceed the PHA’s usual voucher subsidy up to the higher of the rent charged for LIHTC units in the property without additional rent assistance or 110 percent of HUD’s Fair Market Rent (FMR). The new rent incentive for LIHTC owners to accept PBVs was significant in a large number of areas. CBPP analysis revealed that often LIHTC allowable rents were higher than 110 percent of HUD’s FMR (the usual maximum tenant-based voucher subsidy) in metropolitan areas where nearly 60 percent of all metropolitan dwellers lived in 2000. This policy change meant that the rent that PBVs could pay in LIHTC developments located in low-poverty parts of those areas would be higher.[35]

The 2000 amendments to the PBV program were the first time Congress allowed properties to have HUD-funded project-based rental assistance contracts for purposes other than to incentivize developers and owners to secure other funds for construction or rehabilitation. Congress indicated the purpose of this new flexibility was to allow PHAs “to use project-basing as a tool to promote voucher utilization and to expand housing opportunities.”[36] PHAs that secure long-term PBV contracts with owners of existing housing avoid the delays inherent in the construction process and enable waiting list families to access housing without a sometimes lengthy and difficult search process, increasing the share of vouchers families are able to use.

In addition to promoting voucher utilization generally, the flexibility to use PBVs for existing housing can also enable PHAs to help prevent displacement caused by rising rental costs, increase access to higher-opportunity neighborhoods, and promote preservation of affordable housing. In neighborhoods with rapidly rising rents, units with PBV contracts will continue to provide homes for low-income residents paying only 30 percent of income for rent and utilities.[37] In addition, during the term of the contract, the owner is obligated to continue to rent the specified number of project-based units to families eligible for voucher assistance that the PHA refers from its waiting list. PBV contracts can also limit growth in voucher program costs in rapidly escalating rent markets, because PBV policies provide some constraints on increases in rents charged by owners.[38]

By assuring a steady rent stream to repay loans, PBVs can also facilitate a strategy — by PHAs or other mission-driven entities — to purchase existing properties in high-opportunity areas or neighborhoods where greater demand is making rents rise. By project-basing vouchers in these types of areas, more units will be available to families with low incomes at affordable rents.[39] Flexibility to project-base vouchers in existing housing can also be an important tool to preserve properties as affordable when other subsidies or reduced rent requirements expire.

Policymakers and affordable housing advocates also wanted to make sure that a significant share of PHAs would offer the PBV program, and that a sufficient number of owners and developers would be interested in the new contracts. To accomplish these goals, the 2000 amendments substantially streamlined HUD review and other administrative requirements and included new incentives for owners and developers to participate in the PBV program. Tenant advocates also achieved new protections for applicants for PBV units.

Streamlined HUD administrative procedures. The 2000 amendments substantially reduced HUD’s role in PBV programs. For example, PHAs no longer had to get HUD approval to operate a PBV program, to select owners or developers to receive PBV contracts (after a HUD-specified advertisement period), to determine the duration of a PBV contract (up to the new statutory maximum of ten years), or to extend an initial contract with an owner. This streamlining of procedures aimed to reduce administrative costs and delays, making it less burdensome for PHAs to operate the program. Removing the uncertainty and delays inherent in the prior HUD approval requirements could also make the program more attractive to owners and developers.

The statutory changes included other new provisions to make the operation of the PBV program more attractive to PHAs. For example, PHAs are allowed to inspect only a sample of units under a PBV contract in a building rather than inspect each unit periodically, saving staff time on an ongoing basis. The new authority to project-base vouchers in existing housing further streamlines many administrative requirements and could help PHAs meet HUD’s performance standards for voucher utilization.

Overall, PHAs that make use of the revamped PBV program could increase community support by better serving communities in need of additional new construction or rehabilitation of affordable housing, and providing additional units that meet the needs of people with disabilities or older adults.

Longer contract terms. The most important change in the 2000 amendments to encourage developers to participate in the PBV program was permitting contracts to last up to ten years, making the subsidy stream reliable for underwriting purposes. Contract extensions beyond ten years provided long-term affordable units, with new flexibility for owners to decide whether to accept PHA-offered extensions. PHAs could enter into shorter contracts if they wished, for example if they were concerned that future changes in neighborhoods could undermine the desirability or viability of the properties.

Rent and vacancy payment incentives. The amendments also included rent incentives, particularly in lower-poverty neighborhoods. In any type of neighborhood, PBV unit rents could exceed the PHA’s subsidy for regular tenant-based vouchers, up to 110 percent of the Fair Market Rent, as long as the rents are reasonable compared with unassisted units in the area. And in a lower-poverty area, as discussed above, the maximum PBV subsidy for a unit that receives Low Income Housing Tax Credits may exceed 110 percent of the FMR in some situations.[40] The rent flexibility in lower-poverty neighborhoods is particularly important for newly constructed or rehabilitated units, which often command a higher rent than older units. HUD does not set a separate FMR for newly constructed or rehabilitated units.

Another financial incentive for owners was new flexibility for PHAs to provide vacancy payments for up to 60 days, unlike in the regular voucher program which does not permit any vacancy payments. CBPP and others argued that allowing PHAs to provide rent payments when a vacancy is not the owner’s fault was important; it could offset potential owner concerns about reliance on PHAs’ timely referral of families from the PHA waiting list to fill vacant units rather than maintaining their own list of applicants.

Tenant protections. The amendments also included important tenant protections. For example, all families admitted to PBV units had to be referred to owners from the PHA’s waiting list,[41] and all families on the tenant-based waiting list had to be given the option to put their names on any separate PBV waiting list the PHA maintained. These requirements meant that families could apply in one place for voucher assistance, without having to search out properties with PBV contracts. In addition, owners could not arbitrarily reject PHA-referred applicants, because then the vacancy would be the owner’s fault and they would not qualify for vacancy payments. The amendments also codified the prior HUD rule that applicants would not lose their place on a PHA’s tenant-based voucher waiting list due to rejecting an offer of PBV assistance, preventing a future HUD Secretary from changing the policy. (See Appendix Tables 1 and 2 for details on the policy changes mentioned in this section and any later amendments.)

Congress made significant changes in a number of PBV policies after the 2000 program revamp, notably multiple revisions enacted in 2008 and 2016.[42] The two most significant policy changes were a major expansion of the share of a PHA’s overall number of vouchers that can be project-based (the “Program Cap”), and an increase in the share of units in a property that may have PBVs (the “Project Cap”). These statutory changes, which have not yet been fully implemented, are discussed below. For details of other major statutory changes after 2000, see Appendix Table 2.

As part of the 2016 Housing Opportunity Through Modernization Act (HOTMA), Congress substantially expanded the permissible number of PBVs each PHA may administer from the 2000 program cap level of 20 percent of funded vouchers, through three policy changes. HUD implemented most aspects of these policy changes in 2017. Two of the changes increased the number of allowable PBVs by at least 50 percent at each PHA, an increase of potentially more than 300,000 nationally (which will grow if the number of authorized vouchers increases).[43] The third change excludes many PBV units — notably those used to preserve affordable housing — from the program cap calculation, potentially allowing PHAs to project-base most, or even all, of their housing vouchers.

Few PHAs are close to the limit on project-basing as expanded by the 2016 amendments. CBPP analysis of HUD data from January 2022 indicates that out of a total of slightly more than 2,000 agencies administering vouchers, only around 30 PHAs subject to the program cap[44] have project-based 25 percent or more of their authorized vouchers, excluding RAD units, which are exempted from the program cap. The actual number of PHAs approaching the expanded 30 percent cap likely is lower because some of their PBVs may not count toward the cap since they preserve excluded units, such as previously rent-restricted or non-RAD subsidized units, that are not tracked in HUD data.[45]

Even though few (if any) PHAs are approaching the limit on project-basing, some policymakers have indicated a concern that PHAs should be able to project-base more vouchers than the 2016 statutory changes permit. For example, in the report accompanying the bipartisan agreement on the final fiscal year 2023 funding bill for HUD and other agencies, Congress directed HUD to review “the feasibility of relaxing the percentage cap on project-based vouchers, in order to continue providing affordable housing to special needs populations who would otherwise face barriers in finding suitable housing in the private rental market.”[46] Late in the 2022 session, some House members introduced a bill that would increase the base percentage of authorized vouchers allowed to be project-based to 50 percent from 20 percent.[47] Given the complexity of the 2016 amendments that substantially increased PHAs’ authority for project-basing, and HUD’s delay in issuing final regulations implementing these changes,[48] it is perhaps no surprise that policymakers — and many advocates — do not understand the extent of PHAs’ project-basing authority and the fact that few if any are near the limit.

Many families on PHAs’ voucher waitlists prefer a tenant-based voucher so they can live in a neighborhood near relatives, a job, or child’s school, or in housing of their choice, such as a home with a yard.[49] Tenant-based vouchers also may provide access to lower-poverty neighborhoods with higher-performing schools than the locations of a PHA’s PBV-assisted properties. Strong evidence shows that living in such neighborhoods leads to better outcomes for children.[50] Moreover, few PBV units are likely to have sufficient bedrooms for larger families or to offer the private yards many families with children prefer. [51]

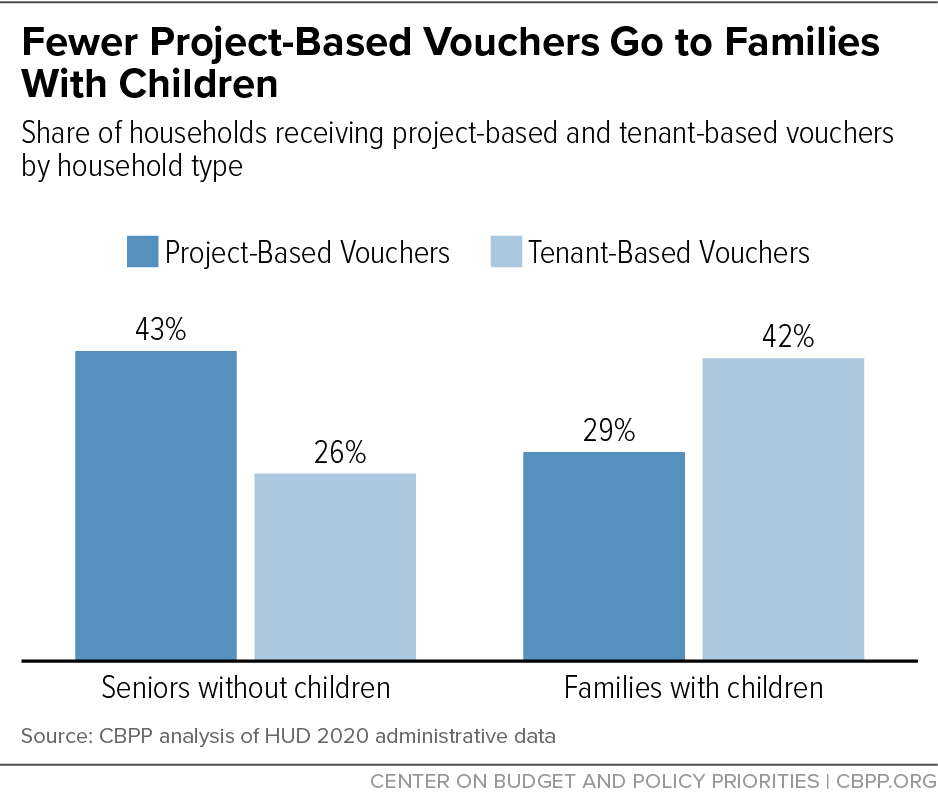

Some PHAs with high rates of project-basing have experienced a distortion in admissions policies. Relatively few project-based units are rented to families with children. (See Figure 2.)[52] Increasing the share of vouchers that are project-based would likely further reduce the overall share of vouchers going to families with children, which has already dwindled from 58 percent in 2004 to 39 percent in 2022.[53] This is problematic, because research shows that vouchers sharply reduce homelessness and housing instability among families with children and have other positive effects as well, including reducing foster care placements, sleep and behavioral problems, and disruptive moves from one school to another.[54]

If the waiting list for a tenant-based voucher is closed or very long, some applicants will accept a PBV unit as a means to get a tenant-based voucher (through the Resident Choice option discussed above).[55] This will likely increase the demand for moving vouchers from households in PBV units that had no intention of remaining in the units any longer than necessary, which will have two harmful consequences: further delaying access to tenant-based vouchers for other households, and increasing owners’ costs and potentially reducing their revenue as a result of more vacancies.

Policymakers should increase capacity for project-basing while avoiding these types of negative consequences by increasing the overall number of housing vouchers, rather than allowing a larger share of existing vouchers to be project-based. This approach would also help address the severe shortage of rental subsidies for all types of low-income households in need — 3 out of 4 of whom do not now receive rental assistance.[56] Or Congress could enact a similar type of subsidy through the tax code.[57]

Units will only be truly affordable for the lowest-income households with the type of tenant rent guarantee that a PBV (or other voucher) provides. Additional grants or tax credits that provide capital to help pay for development costs, however, could reduce the amount developers have to borrow and enable them to offer units at lower, below-market rents as a result. The cost of PBVs in such properties could then be reduced.

The Project Cap policy enacted in 2000 was stricter than many stakeholders had favored, as discussed earlier, and various influential groups sought to loosen it in subsequent legislation. Proponents of affordable housing preservation, advocates for expansion of housing opportunities in low-poverty areas, and anti-homelessness and disability rights groups seeking to expand the availability of supportive housing and housing options in integrated settings for people with disabilities, wanted modifications to the initial statutory policy.

In 2008, Congress made the Project Cap more flexible to implement by making it applicable to multiple buildings that were part of the same project, rather than requiring compliance in each building. This change, for example, allowed a developer of four contiguous 25-unit buildings to comply with the Project Cap by making three of the buildings all market-rate or supported only by Low Income Housing Tax Credits, and concentrating 25 PBVs in the fourth building.

Congress made comprehensive changes in the PBV Project Cap policies in 2016 as part of HOTMA, while retaining the exception from the Project Cap policy for elderly households and a modified exception for units in properties offering supportive services. To fulfill preservation goals, Congress exempted all previously federally assisted or rent-restricted properties from the Project Cap (as well as the program cap, as discussed above). Together with the 2008 shift to measuring the Project Cap across multiple buildings in a single “project,” these changes could significantly reduce or eliminate the likelihood of the residents of a particular building being mixed income.

In addition, Congress increased the share of units that could have PBVs depending on projects’ location and size. These changes could expand access to lower-poverty neighborhoods even if they reduce the diversity of incomes within a property. Projects in low-poverty neighborhoods — those with a poverty rate of 20 percent or less — may have PBVs in up to 40 percent of units, rather than the 25 percent cap enacted in 2000. This change reflects the growing consensus, discussed earlier, that economic integration in neighborhoods may be more beneficial than within a particular property, leading to better outcomes for children and lower crime rates.[58] Similar reasoning supported another change in the PBV cap for “small” properties.[59]

The revised Project Cap policy also recognizes that project-basing is an important strategy to make it easier for families to benefit from voucher subsidies in tight markets. The new policy would allow up to 40 percent of units in a property to receive PBV assistance if tenant-based vouchers are “difficult to use” in the area. Despite the importance of this change in local housing markets with low vacancies and rising rents, HUD has not yet implemented it.[60]

The major PBV policy innovations Congress enacted in 2000, with subsequent modifications, have stood the test of time. Rapid expansion of the PBV program by more than 700 percent from 2010 to 2022 demonstrates its real-world acceptance.[61] Despite initial concerns about whether PHAs would choose to operate a PBV program, and whether owners and developers would partner with them and accept the limitations on the share of units in a property that can have project-based assistance and the possible turnover risks of the Resident Choice requirement, most medium- and large-sized PHAs now operate a PBV program. (See Appendix Table 3.) More than 1 out of 9 households receiving housing voucher subsidies live in PBV units, though that rate differs substantially by agency.[62] PHAs have also opted to shift more than 60 percent of public housing units to PBVs through the Rental Assistance Demonstration rather than direct PBRA contracts with HUD, despite the more stringent policies that apply to the Resident Choice requirement under a PBV contract.[63]

After operating for more than two decades, the revamped PBV program has become an effective tool to provide long-term rental subsidies for a wide variety of purposes, including providing rental homes for low-income families in tight markets,[64] making LIHTC units more affordable,[65] increasing service use in veterans’ supportive housing,[66] and preserving various types of HUD-assisted housing.

The two policies that most distinguish the PBV program from other federal project-based rental assistance programs are the requirements for Project Cap and Resident Choice, discussed in detail above. Together, these policies promote mixed-income properties and expand neighborhood choices by encouraging PHAs to select properties in lower-poverty areas to receive PBV contracts. The policies also allow access to tenant-based vouchers, which enable families to choose to live in neighborhoods with higher-performing schools, or are in closer proximity to well-paying jobs, rather than neighborhoods where HUD-subsidized properties are often located.[67] The policies also bring market-like discipline to property maintenance and management by ensuring that all residents — those receiving a federal rent subsidy as well as those paying market rents — can afford to move out of the property or neighborhood when it no longer meets their needs.

Even without an increase in housing vouchers, the PBV program likely will continue to grow and remain a key tool to secure affordable housing opportunities, particularly in markets that are challenging for use of tenant-based vouchers and for people who need supportive services to retain their housing, such as some individuals with disabilities or those who are experiencing homelessness, including veterans. Policymakers should retain the key innovations underlying the 2000 and later statutory changes in the PBV program — the Project Cap and Resident Choice policies — as well as the related rent and other incentives to locate properties in higher-opportunity neighborhoods, and not expand the current cap on the share of vouchers an agency may project-base. HUD should take steps to ensure key policies are being enforced and work with practitioners, residents, and other stakeholders to learn more about the operation and impact of key program features. These innovations should also be incorporated in any new investment in expansion or preservation of properties with project-based rental assistance, including public housing.

| APPENDIX TABLE 3 |

|---|

|

| | Total PHAs With HCV Program | Authorized HCVs | PHAs With PBVs | Number of PBVs |

|---|

| All Moving to Work (MTW) PHAs | 126 | 514,000 | 97 | 86,000 |

| 550 or fewer total units | 22 | 5,000 | 7 | 1,000 |

| 551 to 6,000 total units | 80 | 172,000 | 69 | 27,000 |

| 6,001 or more total units | 24 | 337,000 | 21 | 58,000 |

| All Non-MTW PHAs | 2,041 | 2,112,000 | 680 | 175,000 |

| 550 or fewer total units | 1,148 | 209,000 | 165 | 8,000 |

| 551 to 6,000 total units | 819 | 1,013,000 | 447 | 76,000 |

| 6,001 or more total units | 74 | 890,000 | 68 | 91,000 |

The paper includes an estimate of the share of authorized vouchers that are project-based at each PHA for purposes of determining whether PHAs are close to reaching the statutory cap on project-basing (known as the program cap). That cap permits agencies to project-base up to 20 percent of their authorized vouchers, plus another 10 percent if the added vouchers are used for units that house people experiencing homelessness or veterans, provide supportive housing for adults age 62 or older or people with disabilities, or are in areas where the poverty rate is 20 percent or less or tenant-based vouchers are otherwise difficult to use and are committed on or after April 18, 2017 — the effective date of most of the relevant HOTMA changes. Units that were previously subject to federally required rent restrictions or received another type of long-term HUD subsidy (including all units converted to project-based vouchers under the Rental Assistance Demonstration, or RAD) and units awarded under HUD-Veterans Affairs Supportive Housing (VASH) project-based voucher set-asides are not counted when determining whether PHAs comply with the cap.[68]

Our estimate of the percentage of vouchers project-based at each PHA is based primarily on HUD administrative data as of January 1, 2022. Our calculation of the numerator — that is, the number of project-based vouchers counted against the cap — starts with the total number of PBVs at the agency, including (1) leased units, (2) units that are under a housing assistance payment (HAP) contract but not currently leased, and (3) units that are under an agreement to enter into housing assistance payment contracts (AHAP). The HUD administrative data we used did not include planned PBV units that are not yet covered by an AHAP or HAP, so those units are not included in our analysis.

Consistent with HUD policy, we then subtracted from the numerator the number of VASH PBV units at the agency that resulted from special allocations by HUD and an estimate of the number of the agency’s PBVs that are part of RAD.[69] RAD units were all previously assisted through other long-term HUD subsidies (primarily public housing), and are excluded from the PBV cap calculation based on HUD’s implementation of 2016 amendments to the U.S. Housing Act or HUD’s RAD implementation policies. Our estimate of the number of RAD units includes units identified in the January 2022 HUD data as leased RAD PBV units. The RAD program does not use AHAPs, so none of the AHAP PBV units identified in HUD’s data should be RAD units.

Some of the unleased PBV units under HAP in the January 2022 HUD data are RAD units, but the data do not indicate how many. We estimated this figure using December 2021 HUD RAD program data on the total number of PBV units converted under the first component of RAD (which primarily consists of former public housing units). We assumed that the number of unleased RAD PBV units equaled the lower of (1) the total number of unleased PBV units in the January 2022 HUD data; or (2) the total number of RAD first component PBV units according to the December 2021 RAD data minus the number of leased first component units according to the January 2022 HUD PBV data.

The number of units we were able to subtract from the numerator misses some types of formerly assisted units that would be excluded from HUD’s program cap calculations. First, it misses unleased PBV units under the second component of RAD, which converts units from several small HUD rental assistance programs. The January 2022 HUD data identifies leased second component RAD PBV units, but we do not have PHA-level data on the total number of these units so we could not estimate how many of the unleased PBV units are second component RAD units. Second, and more significantly, we were not able to identify and subtract PBVs in any formerly assisted units that were not converted under RAD (including non-RAD units in “blended” conversions that include some RAD PBVs and some non-RAD PBVs). For these reasons, our estimates of the number of units that should be subtracted err on the low end, and our estimate of how many PBVs count against the cap (and how many PHAs are close to reaching the cap) should be viewed as conservatively high.

We were also not able to identify how many PBVs were committed on or after April 18, 2017, and how many fall into the categories that allow agencies to project base an added 10 percent of their vouchers.[70] Partly for this reason, this paper’s analysis focuses on how many PHAs have project-based 25 percent or fewer of their vouchers, which leaves them with capacity to project-base at least another 5 percent of their vouchers if the added PBVs are targeted on one of the categories that qualifies for the added 10 percent or are excluded from the program cap calculation. Some of those PHAs, however, may not be able to add more vouchers that are not in those categories.

We calculated the denominator for the project-basing percentage starting with the number of authorized vouchers at each agency as of January 2022 (based on HUD’s Two-Year Projection Tool), and then subtracted the same VASH and RAD units we deducted from the numerator, consistent with HUD’s policy at Notice PIH 2017-21 (October 30, 2017), Attachment F and Appendix I (including the linked PBV Program Cap Calculation Worksheet, updated July 2022).

Rachel G. Bratt, “What May Work about the Mixed-Income Approach: Reflections and Implications for the Future,” in Joseph and Khare, eds., pp. 697-722.

CBPP, “Policy Basics: The Housing Choice Voucher Program,” updated April 12, 2021, https://www.cbpp.org/research/housing/the-housing-choice-voucher-program.

CBPP, “Policy Basics: Project-Based Vouchers,” updated July 11, 2023, https://www.cbpp.org/research/housing/project-based-vouchers.

CBPP, “Policy Basics: Public Housing,” updated June 16, 2021, https://www.cbpp.org/research/public-housing.

CBPP, “Policy Basics: Section 8 Project-Based Rental Assistance,” updated January 10, 2022, https://www.cbpp.org/research/housing/section-8-project-based-rental-assistance.

Raj Chetty et al., “Social capital II: determinants of economic connectedness,” Nature, 608, 122-134 (2022), https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-022-04997-3. For a non-technical explanation of the research and findings, see Opportunity Insights’ Social Capital Atlas at https://socialcapital.org/?dimension=EconomicConnectednessIndividual&geoLevel=county&selectedId=&dim1=EconomicConnectednessIndividual&dim2=CohesivenessClustering&dim3=CivicEngagementVolunteeringRates&bigModalSection=&bigModalChart=scatterplot&showOutliers=false&colorBy=.

Raj Chetty, Nathaniel Hendren, and Lawrence Katz, “The Effects of Exposure to Better Neighborhoods on Children: New Evidence from the Moving to Opportunity Experiment,” American Economic Review, April 2016, pp. 855-902. (This study was first released in 2015, see http://www.equality-of-opportunity.org/images/mto_paper.pdf.)

Melissa Chinchilla et al., “Comparing Tenant and Neighborhood Characteristics of the VA's Project- vs. Tenant-Based Supportive Housing Program in Los Angeles County,” Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved, November 2019, https://muse-jhu-edu.libproxy.utdallas.edu/article/737218/pdf.

Mary Cunningham and Molly Scott, “The Resident Choice Option: Reasons Why Residents Change from Project-Based Vouchers to Portable Housing Vouchers,” Urban Institute, June 2010, https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/28761/412121-The-Resident-Choice-Option-Reasons-Why-Residents-Change-from-Project-Based-Vouchers-to-Portable-Housing-Vouchers.PDF.

Will Fischer, Douglas Rice, and Alicia Mazzara, “Research Shows Rental Assistance Reduces Hardship and Provides Platform to Expand Opportunity for Low-Income Families,” CBPP, December 5, 2019, https://www.cbpp.org/research/housing/research-shows-rental-assistance-reduces-hardship-and-provides-platform-to-expand.

Will Fischer, “Low Income Housing Tax Credit Could Do More to Expand Opportunity for Poor Families,” CBPP, August 28, 2018, https://www.cbpp.org/sites/default/files/atoms/files/8-28-18hous.pdf.

Lance Freeman, “The Siting Dilemma: Race and the Location of Federal Housing Projects,” in Molly W. Metzger and Henry S. Webber, Facing Segregation, Oxford University Press (2019).

Martha Galvez et al., “Moving to Work Agencies’ Use of Project-Based Voucher Assistance,” Urban Institute, April 2021, https://www.huduser.gov/portal/sites/default/files/pdf/MTW-Project-Based-Voucher-Assistance.pdf.

Erik Gartland, “Chart Book: Funding Limitations Create Widespread Unmet Need for Rental Assistance,” CBPP, February 15, 2022, https://www.cbpp.org/research/housing/funding-limitations-create-widespread-unmet-need-for-rental-assistance.

Mark L. Joseph and Amy T. Khare, eds., What Works to Promote Inclusive, Equitable Mixed-Income Communities, National Initiative on Mixed-Income Communities and Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco (2020).

Jill Khadduri, “The Founding and Evolution of HUD: 50 Years, 1965 – 2015,” Chapter 1 in HUD at 50: Creating Pathways to Opportunity, HUD Office of Policy Development and Research (2015).

Brent Mast and David Hardiman, “Project-Based Vouchers,” Cityscape 19:2 (2017), pp. 301- 322, n. 2, https://www.huduser.gov/portal/periodicals/cityscpe/vol19num2/ch21.pdf.

Alicia Mazzara, Barbara Sard, and Douglas Rice, “Rental Assistance for Families with Children at Lowest Point in Decade,” CBPP, October 18, 2016, https://www.cbpp.org/research/housing/rental-assistance-to-families-with-children-at-lowest-point-in-decade.

Millennial Housing Commission, “Meeting Our Nation’s Challenges,” Report of the Bipartisan Millennial Housing Commission (May 2002).

Kathryn Nelson et al., “Trends in Worse Case Needs for Housing, 1978 – 1999: A Report to Congress on Worst Case Housing Needs,” Department of Housing and Urban Development, December 2003, https://www.huduser.gov/portal/publications/affhsg/worstcase03.html.

Stephen Norman and Sarah Oppenheimer, “Expanding the Toolbox: Promising Approaches for Increasing Geographic Choice,” Joint Center for Housing Studies, p. 14, https://www.jchs.harvard.edu/sites/default/files/media/imp/a_shared_future_expanding_the_toolbox_0.pdf.

Richard Rothstein, The Color of Law, Liveright Publishing Corporation (2017).

Michaeljit Sandhu, “Reassessing Market-Rate Residents’ Role in Mixed-Income Developments,” in Joseph and Khare, eds., pp. 490-509.

Barbara Sard et al., “Federal Policy Changes Can Help More Families with Housing Vouchers Live in Higher-Opportunity Areas,” CBPP, September 4, 2018, https://www.cbpp.org/sites/default/files/atoms/files/9-4-18hous.pdf.

Barbara Sard, “Congress Unanimously Approves Bill to Improve Housing Programs,” CBPP, July 15, 2016, https://www.cbpp.org/blog/congress-unanimously-approves-bill-to-improve-housing-programs.

Barbara Sard, “Housing Vouchers Should Be a Major Component of Future Housing Policy for the Lowest Income Families,” Cityscape 5:2 at 89, 94 (2001a).

Barbara Sard, “Revision of the Project-Based Voucher Statute,” CBPP, revised April 26, 2001, https://www.cbpp.org/sites/default/files/archive/10-25-00hous.pdf.

Dennis W. Snook and E. Richard Bourdon, “Appropriations for FY2001: VA, HUD, and Independent Agencies (P.L. 106-377),” CRS Report for Congress, updated November 17, 2000.

Rod Solomon, Public Housing Reform and Voucher Success: Progress and Challenges, The Brookings Institution Metropolitan Policy Program (2005).

Mark Treskon et al., “Evaluation of the Rental Assistance Demonstration (RAD): Early Findings on Choice Mobility Implementation (2023), https://www.huduser.gov/portal//portal/sites/default/files/pdf/RAD-Early-Findings-on-Choice-Mobility-Implementation.pdf.

Margery Austin Turner, Susan J. Popkin, and Lynette Rawlings, Public Housing and the Legacy of Segregation, The Urban Institute Press (2009).

U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), 2022 Picture of Subsidized Households, https://www.huduser.gov/portal/datasets/assthsg.html.

U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), “Confronting Concentrated Poverty with a Mixed-Income Strategy,” Evidence Matters, Spring 2013, https://www.huduser.gov/portal/periodicals/em/spring13/highlight1.html.