- Home

- Creating Opportunity For Children

Creating Opportunity for Children

How Housing Location Can Make a Difference

Executive Summary

Most parents want to raise their children in neighborhoods with good schools, safe streets, and neighbors who support their efforts to raise healthy, happy, and successful families. Their hopes are well-placed because a growing body of evidence supports two conclusions about how neighborhoods affect children’s well-being.

First, high-poverty neighborhoods, which are often violent, stressful, and environmentally hazardous, can impair children’s cognitive development, school performance, mental health, and long-term physical health. Second, poor children who live in low-poverty neighborhoods and consistently attend high-quality schools — where more students come from middle- or high-income families and do well academically, parents are more involved, teachers are likely to be more skilled, staff morale is higher, and student turnover is low — perform significantly better academically than those who do not.

Nearly 4 million children live in families that receive federal rental assistance. This assistance not only helps these families to afford decent, stable housing and make ends meet, but it also has the potential to enable their children to grow up in better neighborhoods and thereby enhance their chances of long-term health and success. Historically, however, federal rental assistance programs have fallen short in helping families live in neighborhoods that provide these opportunities.

Over several decades, policymakers have adopted measures to reduce the extent to which low-income families receiving federal rental assistance are concentrated in distressed neighborhoods and, instead, to improve these families’ access to safe neighborhoods with good schools, more opportunities for recreation and enrichment, and better access to jobs. To do so, policymakers have relied increasingly on housing vouchers (rather than housing projects) so that families may choose where to live rather than be limited to government-funded projects that often are situated in very poor, segregated neighborhoods.

Despite these efforts, in 2010 only 15 percent of the children in families that received rent subsidies through the Department of Housing and Urban Development’s (HUD) three major rental assistance programs — the Housing Choice Voucher (HCV) program, public housing, and Section 8 Project-Based Rental Assistance (as described in Box 1) — lived in low-poverty neighborhoods, where fewer than 10 percent of the residents had incomes below the poverty line. A greater share of such children (18 percent) lived in extreme-poverty neighborhoods, where at least 40 percent of the residents are poor.[1]

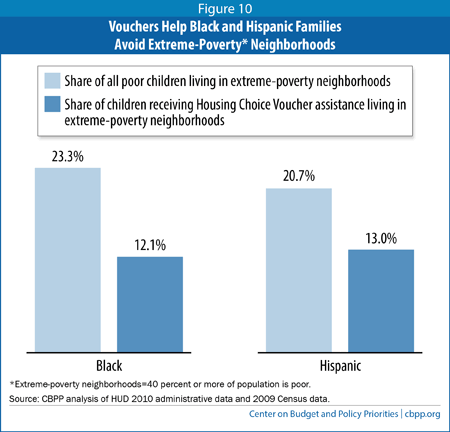

The HCV program has performed much better than HUD’s project-based rental assistance programs in enabling more low-income families with children — and particularly more African American and Latino families — to live in lower-poverty neighborhoods. (Only a small share of public housing or privately owned units with project-based rental assistance for families with children are in low-poverty neighborhoods.) Having a housing voucher also substantially reduces the likelihood of living in an extreme-poverty neighborhood, compared with similar families with children that either receive project-based rental assistance or don’t receive housing assistance at all.

Box 1: What Is Federal Rental Assistance?

Federal rental assistance enables 5 million low-income households to afford modest homes. Three major programs — Housing Choice Vouchers, Section 8 Project-Based Rental Assistance, and Public Housing — assist about 90 percent of these households.a In each of these programs, families generally pay 30 percent of their income for rent and utilities.

Housing Choice Vouchers: More than 5 million people in more than 2 million low-income households use housing vouchers. About half of these households have minor children in the home. Families use housing vouchers to help pay for modestly priced, decent-quality homes in the private market. The program is federally funded but run by a network of about 2,300 state and local housing agencies.

Public Housing: About 2.2 million people in nearly 1 million low-income households live in public housing. Forty percent of these households include children, while more than half are headed by people who are elderly or have disabilities. While federally funded, public housing is owned and operated by 3,100 local housing agencies nationwide.

Section 8 Project-Based Rental Assistance (PBRA): PBRA enables 2 million people in more than 1 million households to afford modest apartments, due to long-term rental assistance contracts between the private owners and the Department of Housing and Urban Development. About 30 percent of these households include children. Two-thirds are headed by people who are elderly or have disabilities.

a For more on these programs, see Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, “Policy Basics: Federal Rental Assistance,” January 25, 2013, https://www.cbpp.org/cms/index.cfm?fa=view&id=3890.

Nevertheless, a quarter of a million children in the HCV program live in these troubled neighborhoods despite the better options that a voucher should make available to them. As now administered, the HCV program does not adequately deliver on its potential to expand children’s access to good schools in safe neighborhoods. It can do better.

Based on the evidence on how housing location affects low-income families, particularly children, and the performance of federal rental assistance programs on location-related measures, we recommend two closely related near-term goals for federal rental assistance policy: 1) federal rental assistance programs should provide greater opportunities for families to choose affordable housing outside of extreme-poverty neighborhoods; and 2) the programs should provide better access for families to low-poverty, safe communities with better-performing schools.

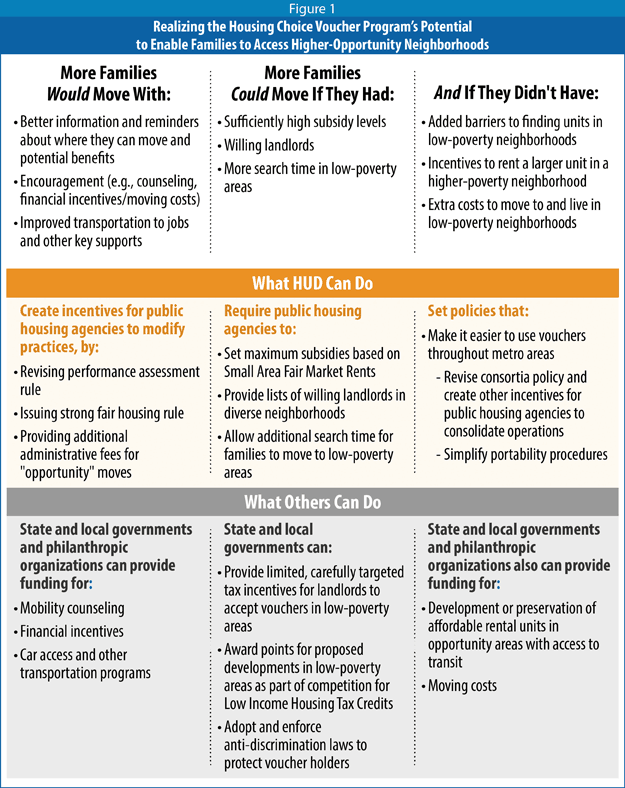

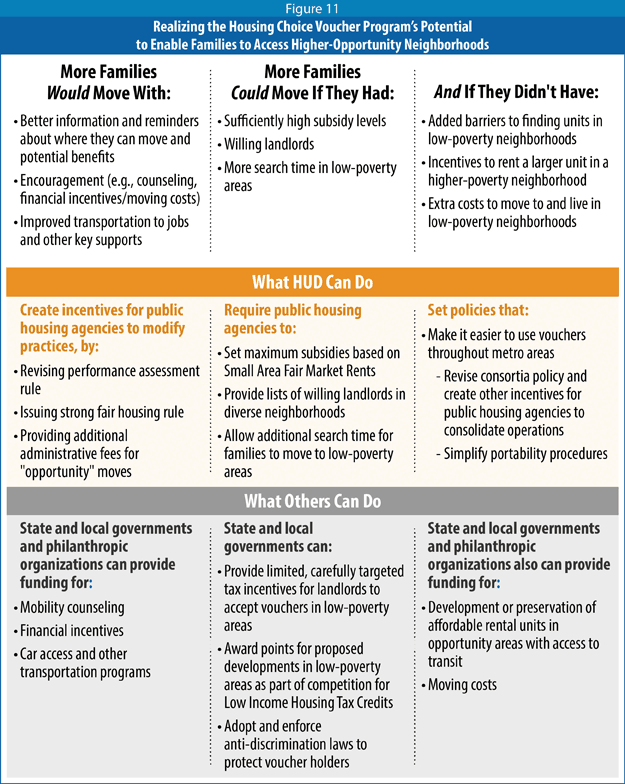

We can make substantial progress toward these goals in the next few years, even in the current fiscally constrained environment and even without congressional action or more funding. Federal, state, and local agencies can make four sets of interrelated policy changes that can help more families in the HCV program to live in better locations. (See Figure 1.)

- Create strong incentives for local and state housing agencies to achieve better location outcomes. Federal policy should provide incentives for agencies to reduce the share of families using vouchers in extreme-poverty areas and increase the share residing in low-poverty, high-opportunity areas. HUD could do this in three ways: by giving added weight to location outcomes in measuring agency performance, reinforcing these changes with a strong fair housing rule — the rule that will revise HUD grantees’ planning for how to achieve outcomes that further fair housing goals — and rewarding agencies that help families move to high-opportunity areas by paying these agencies additional administrative fees.

- Modify policies that discourage families from living in lower-poverty communities. Various HCV program policies impede families from moving to low-poverty areas and thereby unintentionally encourage families to use their vouchers in poor neighborhoods that often are highly racially concentrated. (Most extremely poor neighborhoods are predominantly African American and/or Latino.) HUD should finalize its proposed rule on public housing agencies’ fair housing obligations. It also should set its caps on rental subsidy amounts for smaller geographic areas than it now does, and — at least where necessary to help families move from extreme-poverty, highly racially concentrated neighborhoods to higher-opportunity communities with less poverty — require agencies to identify available units in these lower-poverty communities and extend the search period for families seeking to make such moves.

- Minimize jurisdictional barriers to families’ ability to choose to live in high-opportunity communities. HUD should modify the HCV program’s administrative geography to substantially reduce the extent to which the boundaries of housing agencies’ service areas impede the program’s ability to promote access to higher-opportunity neighborhoods. HUD could substantially lessen these barriers by encouraging agencies in the same metropolitan area to unify their program operations and by simplifying “portability” procedures.

- Assist families in using vouchers to live in high-opportunity areas. To expand housing choices in safe, low-poverty neighborhoods with well-performing schools, state and local governments and housing agencies should adopt policies — such as tax incentives and laws prohibiting discrimination against voucher holders — to expand participation by landlords in these neighborhoods in the HCV program and to encourage interested families to use their vouchers in these areas. Such assistance for families could include financial incentives to offset the additional costs of moving to high-opportunity areas, mobility counseling, and programs to expand access to cars and other transportation to and from these areas.

This focus on enhancing families’ ability to choose to move to areas with more opportunities for their children (or to remain in affordable housing in lower-poverty, high-opportunity neighborhoods) does not imply that policymakers should not pursue broader strategies to increase incomes, enhance safety, and improve educational performance in very poor areas. Quite the contrary. Nevertheless, those strategies often take many years to implement and can be costly, and in many cases, we don’t know very much about their effectiveness.

HUD has begun two programs that, over time, may make a significant difference for children living in public housing or privately-owned assisted housing. The Choice Neighborhoods Initiative provides funding to revitalize distressed HUD-funded properties as a means to support the broader goal of improving residents’ lives, as well as conditions in the surrounding neighborhoods, with parallel investments by partner agencies in education and public safety. In addition, the Rental Assistance Demonstration enables public housing agencies to leverage private funding to rehabilitate and preserve their properties, while giving residents a choice to move with tenant-based rental assistance. If implemented well and expanded, both programs have the potential to help more families live in higher-opportunity neighborhoods.

Helping children and their families to avoid living in violent neighborhoods of extreme poverty and enabling more of the families receiving federal rental assistance to live in low-poverty neighborhoods with high-quality schools should be high-priority goals for federal housing policy.

This paper has three sections. In Section 1, we review the evidence on how neighborhoods affect children; in Section 2, we outline where children in families with rental assistance live; and, in Section 3, we explain the key policy changes needed in federal rental assistance programs to create more opportunity for low-income children.

Table of Contents

- Executive Summary

- Section 1: For Better and for Worse, Neighborhoods Affect Low-Income Children’s Well-Being and Success

- Growing Evidence Links Living in Neighborhoods of Extreme Poverty to Impairments in Children’s Cognitive Development and Physical Health

- Damaging Effects of Toxic Stress

- MTO Families Did Not Experience Economic Gains for Adults or Educational Gains for Children

- Gautreaux Families Experienced Large and Long-Lasting Neighborhood Improvements That Appear to Have Benefited Children

- Moving to Opportunity’s Disappointing Educational Results May Be Related to Study’s Limitations

- Rigorous Study Provides Evidence That High-Opportunity Neighborhoods Improve Children’s Educational Achievement

- Conclusion

- Growing Evidence Links Living in Neighborhoods of Extreme Poverty to Impairments in Children’s Cognitive Development and Physical Health

- Section 2: Federal Rental Assistance Could Do More to Provide Access to Areas of Opportunity

- Families Using Housing Vouchers More Likely to Live in Low-Poverty Areas Than Other Similar Families

- How Federal Rental Assistance Programs Affect the Likelihood That Children Will Live in Extreme-Poverty Neighborhoods.

- Federal Rental Assistance Programs’ Impact on Access to Better-Performing Schools and Safer Neighborhoods

- Weakened Economy Has Undercut Efforts to Increase Voucher Holders’ Access to Lower-Poverty Neighborhoods Since 2000

- Conclusion

- Section 3: Improving Outcomes for Children in HUD's Rental Assistance Programs

- Recommendations: Realizing the Housing Choice Voucher Program’s Potential to Enable Families to Access Higher-Opportunity Neighborhoods

- Create Strong Incentives for Housing Agencies to Achieve Better Location Outcomes

- Modify Policies That Discourage Families From Living in Lower-Poverty Communities

- Minimize Jurisdictional Barriers to Families’ Ability to Choose to Live in High-Opportunity Communities

- Assist Families in Using Vouchers in High-Opportunity Areas

- Expanding Access to Higher-Opportunity Areas in HUD’s Project-Based Rental Assistance Programs

- Conclusion

- Recommendations: Realizing the Housing Choice Voucher Program’s Potential to Enable Families to Access Higher-Opportunity Neighborhoods

- References

Figures and Tables

Figures

Figure 1: Realizing the Housing Choice Voucher Program’s Potential to Enable Families to Access Higher-Opportunity Neighborhoods

Figure 2: Vouchers Cut Families' Exposure to Neighborhood Poverty, But Differences Among Groups Shrank Over Time

Figure 3: Key Elements of Moving to Opportunity (MTO) Families’ Experience

Figure 4: Moving to a Lower-Poverty Neighborhood Improved Adult Health

Figure 5: Low-Income Children Attending Low-Poverty Schools Made Strong Gains in Math and Reading, Compared With Children in Moderate- to High-Poverty Schools

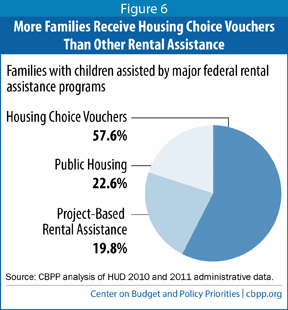

Figure 6: More Families Receive Housing Choice Vouchers Than Other Rental Assistance

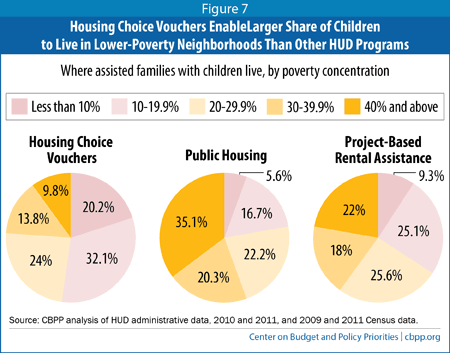

Figure 7: Housing Choice Vouchers Enable Larger Share of Children to Live in Lower-Poverty Neighborhoods Than Other HUD Programs

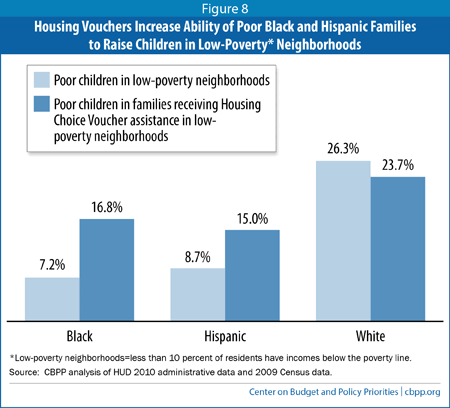

Figure 8: Housing Vouchers Increase Ability of Poor Black and Hispanic Families to Raise Children in Low-Poverty* Neighborhoods

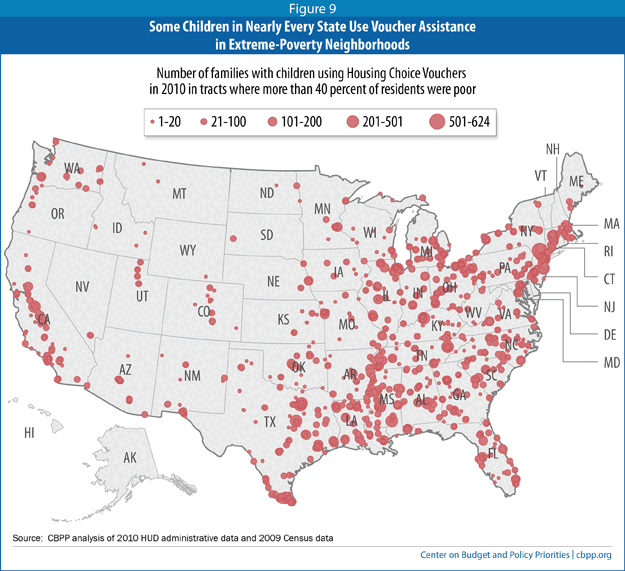

Figure 9: Some Children in Nearly Every State Use Voucher Assistance in Extreme-Poverty Neighborhoods

Figure 10: Vouchers Help Black and Hispanic Families Avoid Extreme-Poverty Neighborhoods

Figure 11: Realizing the Housing Choice Voucher Program’s Potential to Enable Families to Access Higher-Opportunity Neighborhoods

Figure 12: Most Families in Public Housing or Project-Based Assisted Housing in Extreme-Poverty Neighborhoods Are Minorities

Tables

Table 1: Families Receiving Rental Assistance More Likely Than Poor Households and All Renters to Live Near Lower-Performing Schools

Table 2: Housing Vouchers Reduce Exposure to Neighborhood Violence

Table 3: Use of Vouchers Declined in Low-Poverty Neighborhoods and Rose in High-Poverty Neighborhoods Between 2000 and 2010, as the Economy Slumped and Poverty Increased

Appx. Table 1: Where Assisted Families With Children Live, by Poverty Concentration

Appx. Table 2: Racial and Ethnic Composition of Assisted Families With Children, by Program

End notes:

[1] These terms and definitions for “low-poverty” and “extreme-poverty” areas come from the Census Bureau.

Section 1: For Better and for Worse, Neighborhoods Affect Low-Income Children’s Well-Being and Success

Most parents want to raise their children in neighborhoods with good schools, safe streets, and neighbors who support their efforts to raise healthy, happy, and successful families. Conversely, most people believe that children’s chances of being healthy and successful are diminished when they grow up in neighborhoods where violence and crime are common, the schools are ineffective, and young people face enticements to engage in risky or destructive behaviors. Indeed, parents with sufficient resources typically pay more to secure housing in safe, healthy neighborhoods with good schools, thereby placing a large bet on the importance of neighborhoods to their children’s well-being.

Evidence supports such sentiments. Many studies find evidence of the influence of neighborhood poverty, for example, on children’s behavioral and emotional health, cognitive development, and educational achievement.[1] Other studies find significant associations between neighborhood poverty and adult employment, earnings, and related outcomes.[2] Residents of poor neighborhoods also tend to experience health problems — including depression, asthma, diabetes, and heart disease — at higher-than-average rates.[3]

It is particularly hard, however, to disentangle the influences of individual, family, neighborhood, and broader socio-economic factors on the well-being of children and adults. Researchers have thus found it difficult to identify the neighborhood qualities that matter most, to determine how strongly these qualities influence individual outcomes relative to family traits and other influences, and to understand the causal mechanisms at work.[4]

Adding to the difficulties, studies of poor families that have relocated from high-poverty neighborhoods to lower-poverty areas have shown mixed results. In particular, the Moving to Opportunity (MTO) demonstration — a major experimental study launched in the mid-1990s in five cities by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) — found striking improvements in mental health for girls and mental and physical health for mothers, but also negative mental health outcomes for boys and no economic gains for adults or educational gains for children. The absence of positive findings on the impacts of moving to lower-poverty neighborhoods on employment and education was disappointing and appeared to be inconsistent with the findings of other residential mobility studies, such as the influential but less rigorous studies of the Gautreaux program in Chicago, which was created as a result of the 1976 settlement of a lawsuit challenging segregation in public housing.

Recent research has made progress, however, in explaining these inconsistencies and clarifying how neighborhoods can affect children’s health and well-being. For example, a recent series of studies led by sociologists Robert J. Sampson and Patrick Sharkey found evidence that living in neighborhoods of concentrated disadvantage — defined in terms of racial segregation, rates of unemployment and welfare receipt, and the share of single-parent families — can impair children’s cognitive development and school performance, and that exposure to neighborhood violence is an important factor in these results.

These studies are consistent with the burgeoning research in neuroscience, molecular biology, epidemiology, developmental psychology, and related areas about the harmful effects on children of toxic stress, which supports the hypothesis that living in high-poverty neighborhoods can impair children’s cognitive development.

Follow-up research has also highlighted some of the MTO study’s important limitations and suggested that these limitations may have influenced key outcomes, particularly the disappointing educational outcomes for children. Meanwhile, a rigorous study by RAND researcher Heather Schwartz of low-income children living in public housing in Montgomery County, Maryland has independently bolstered the case for Gautreaux’s conclusion that low-poverty, high-opportunity neighborhoods can improve children’s educational achievement. These studies all are discussed in more detail below.[5]

This recent work, combined with earlier research, supports the following conclusions:

- High-poverty neighborhoods, which are often violent, stressful, and environmentally hazardous, can impair children’s cognitive development, school performance, mental health, and long-term physical health.[6] These effects occur both directly and indirectly by affecting, for example, parents’ mental health and parenting practices.

- Poor children who live for many years in low-poverty neighborhoods with high-quality schools — where more students come from middle- or high-income families and do well academically, parents are more involved, teachers are likely to be more skilled, staff morale is higher, and student turnover is low — perform significantly better academically than those who do not.[7]

These conclusions have clear implications for housing policy. First, housing policy should help children and their families to avoid living in violent neighborhoods of very high poverty; and second, it should help poor children and their families to live in low-poverty neighborhoods with high-quality schools. Of course, these conclusions also underscore the importance of broader policies to reduce the incidence as well as the concentration of poverty, revitalize poor neighborhoods, improve public safety in such neighborhoods, and improve school outcomes for disadvantaged children. But with nearly 4 million children living in families that receive federal housing assistance, achieving better results for children in these programs should be an important public policy goal.

Growing Evidence Links Living in Neighborhoods of Extreme Poverty to Impairments in Children’s Cognitive Development and Physical Health

Numerous studies show strong correlations between neighborhood (and school) poverty and poor student academic performance. In 2008-2009, for example, one-half of fourth and eighth graders in high-poverty schools failed the national reading test, compared with fewer than one in five children in low-poverty schools.[8] As noted, however, researchers have found it difficult to separate and measure the relative influence of family traits, school quality, and neighborhood characteristics other than school quality on students’ performance.

A recent series of statistical studies led by sociologists Robert J. Sampson and Patrick Sharkey attempts to address the questions about causality. These studies find consistent evidence that living in neighborhoods of concentrated disadvantage adversely affects children.

For example, a study of 6- to 12-year-old African American children in Chicago tracked students over time as they moved into and out of neighborhoods of concentrated disadvantage. The researchers were able to estimate the effects of neighborhoods on these children as their families moved and to isolate these effects from many non-neighborhood factors such as parents’ welfare receipt, income, work status, and marital status.

They found that children living in neighborhoods of concentrated disadvantage had reduced verbal ability — which research shows is a major predictor of educational, employment, and other important life outcomes — by a magnitude equal to one to two years of schooling.[9] Equally striking, the harmful effects not only became stronger the longer that children were exposed to such environments but lingered even after children had left the neighborhoods.[10]

Box 2: Measures of Neighborhood Poverty

Technically, the “neighborhood poverty rate” is the percentage of people in a census tract with incomes below the poverty line. But researchers and policymakers often use the rate of neighborhood poverty as a proxy for a complex set of factors that can influence the well-being of children and adults. These factors include but are not limited to: neighbors’ affluence, educational attainment, employment, welfare receipt, and marriage status; racial concentration; housing conditions; school quality; the availability of services and resources; and the incidence of crime. Researchers commonly use data at the census tract level (a census tract includes roughly 4,000 residents) because of confidentiality and other issues that arise in using data from smaller geographic areas, although census tracts are only a rough approximation of the geographic area of a “neighborhood.”

Just as poverty is not distributed evenly across neighborhoods, neither are these associated factors, and there is only a rough correspondence between poverty rates and the presence or absence of the associated factors in neighborhoods. While poor neighborhoods are generally more likely to experience higher crime rates than low-poverty neighborhoods, for example, two neighborhoods with identical poverty rates may exhibit very different crime patterns.

Research suggests that neighborhood poverty rates of 15-20 percent are a tipping point — that is, the point at which social problems associated with neighborhood poverty often begin to appear; these problems generally worsen at higher poverty rates, hitting a plateau at a poverty rate of about 40 percent.a Accordingly, the U.S. Census Bureau defines a “poor area” as a census tract with a poverty rate of at least 20 percent, and an “extreme-poverty area” as one with a poverty rate of at least 40 percent. An area with a poverty rate of less than 10 percent is designated a “low-poverty area.” Researchers use various measures of “concentrated poverty”; some define such areas as tracts with poverty rates of 30 percent or more, while others focus on areas with poverty rates of at least 40 percent.

Recognizing that neighborhood poverty rates are only a rough proxy for a variety of conditions that affect families, researchers often construct concepts of “concentrated disadvantage” or “high opportunity” that go beyond poverty rates. For example, the 2008 study led by Sampson discussed in this report uses a concept of “concentrated disadvantage” that combines measures of welfare receipt, unemployment, single-mother parenthood, child density, and racial composition, as well as poverty. At the other end of the spectrum, Margery Austin Turner and her colleagues have developed a concept of “high-opportunity” area based on measures of labor force participation, college completion, racial concentration, and job density, as well as poverty.b

For simplicity, we have chosen to focus on the extremes: low-poverty neighborhoods (where rates are less than 10 percent) and extreme-poverty neighborhoods (rates of at least 40 percent). Among neighborhoods fitting into one or the other of these categories, the variation in other factors that potentially affect well-being — such as crime rates and school quality — is relatively modest, which helps in drawing conclusions. The measures we have chosen also align with metrics that the Department of Housing and Urban Development uses in federal rental assistance programs.c

a Galster (2002), (2008), and (2012).

b Turner et al. (2012). Under the direction of john a. powell, the Kirwan Institute has developed sophisticated tools for mapping “opportunity” in neighborhoods and other geographic areas.

c For instance, HUD defines a “low-poverty census tract” in part as one with a poverty rate below 10 percent (24 C.F.R. 985.3(h)). HUD also has proposed to focus required efforts to “affirmatively further fair housing” on areas where 40 percent or more of the residents are poor and a majority are members of racial or ethnic minority groups.

The researchers identified various plausible mechanisms that could explain these outcomes: a fear of violence and other factors that may limit children’s interactions with others or affect parenting practices, perhaps by affecting parents’ mental health; poor school quality in neighborhoods of concentrated disadvantage; and the high degree of social and ethnic segregation found in the poor neighborhoods studied, which may narrow the “speech community” to which children are exposed.

A series of compelling studies led by Patrick Sharkey strongly supports the hypothesis that exposure to neighborhood violence –– which is more common in neighborhoods of extreme poverty –– has significant negative effects on children’s cognitive performance.[11] One study found that when preschool children were assessed within a week of a homicide occurring near their home, they were less able to control their impulses and pay attention, and they scored lower on pre-academic vocabulary and math tests.[12] (Researchers also found elevated levels of stress among the parents, which suggests that parental stress may be a causal pathway by which violence influences children’s performance, a hypothesis that is consistent with the research on toxic stress discussed below as well as the Sampson study discussed above.)

A more recent study by Sharkey, issued earlier this year,[13] compared the standardized test performance of New York City students in the week before a violent crime occurred on their block with that of students in the week after such crimes. The researchers found that exposure to violence significantly reduced students’ performance on English language assessments, particularly for African American students. Among African American students, the effect on scores was equivalent to 13 percent of the black-white gap in test scores and reduced students’ passing rates by 3 percentage points. Sharkey et al. note that while their study directly examines only the short-term effects of neighborhood violence, it has implications for students’ longer-term success, particularly if they are exposed to repeated incidents of violence over the course of a school year.[14]

These studies have limitations. For instance, while Sampson and his colleagues attempt to distinguish the causal effects of neighborhoods of concentrated disadvantage from family characteristics, these methods cannot fully exclude the possibility that unobserved individual or family characteristics, rather than neighborhood characteristics, are driving the results. (It is difficult to see, however, how individual or family characteristics might be large confounding factors in Sharkey et al.’s study of neighborhood violence and children’s cognitive performance, particularly the 2014 study, as such factors would have to be causally linked to the timing of homicides.)

Damaging Effects of Toxic Stress

These studies are consistent with parts of the growing research in neuroscience, molecular biology, epidemiology, and developmental psychology about the harmful effects of toxic stress, which constitutes a second major body of evidence in support of the hypothesis that living in high-poverty neighborhoods can impair children’s cognitive development. “Toxic stress” occurs when a child experiences frequent, prolonged, or excessive fear or anxiety as a result of being exposed to abuse, neglect, violence, or severe hardship, particularly when the child does not receive adequate adult support in coping with the stress. While much of the toxic stress research has focused on the effects of child abuse and family dysfunction, neighborhoods of concentrated disadvantage can also contribute.[15]

Severe stress can negatively affect the health and well-being of people at any age, but toxic stress appears to be particularly damaging to young children whose brains and bodies are still developing. Toxic stress affects brain development, early learning, and the body’s stress response system in ways that can have a long-term effect on young children’s cognitive development and physical health.[16] Research shows, for example, that toxic stress affects brain development in the areas that regulate emotion and executive function, the latter of which includes the ability to create and follow plans, focus attention, inhibit impulses, and incorporate new information –– abilities essential to children’s success in school. Toxic stress has also been linked to physical changes that increase the risk of long-term health problems such as heart disease.

Nurturing support from parents and other adults can mitigate the effects of stress on children. Yet poor parents living in high-poverty neighborhoods themselves experience hardships, stresses, and stress-related problems at higher rates than non-poor adults who don’t live in high-poverty neighborhoods, and these problems can hinder their ability to provide nurturing support for their children (and may engender or exacerbate negative outcomes among children). For example, the incidence of maternal depression, which can affect parenting patterns in ways that undermine the healthy development of children, is much higher among poor mothers than non-poor mothers, and there is strong evidence that neighborhood poverty is a contributing factor to this trend.[17] Researchers also have linked higher levels of stress hormones in poor pregnant mothers to a range of poor developmental outcomes for children.[18] (Similarly, chronic health problems, which also can hamper parents’ ability to provide support to their children, occur more frequently than average among people living in high-poverty neighborhoods.)

Indeed, the research evidence on the causes and effects of toxic stress is so compelling that the American Academy of Pediatrics has adopted a formal policy statement urging policymakers to reshape policy and the provision of services in ways that “reduce the precipitants of toxic stress in young children and to mitigate their negative effects on the course of development and health across the lifespan.”[19] The policy statement explicitly cites “community-level” (or neighborhood) factors such as violence as a specific risk factor for toxic stress.

These findings point to a strong relationship between the conditions found in extreme-poverty neighborhoods — particularly the incidence of violence and other stressors — and children’s cognitive development and long-term health.

Understanding the Moving to Opportunity Demonstration Findings

The aforementioned research raises the question: can children and adults benefit by moving out of high-poverty neighborhoods and into better neighborhoods?

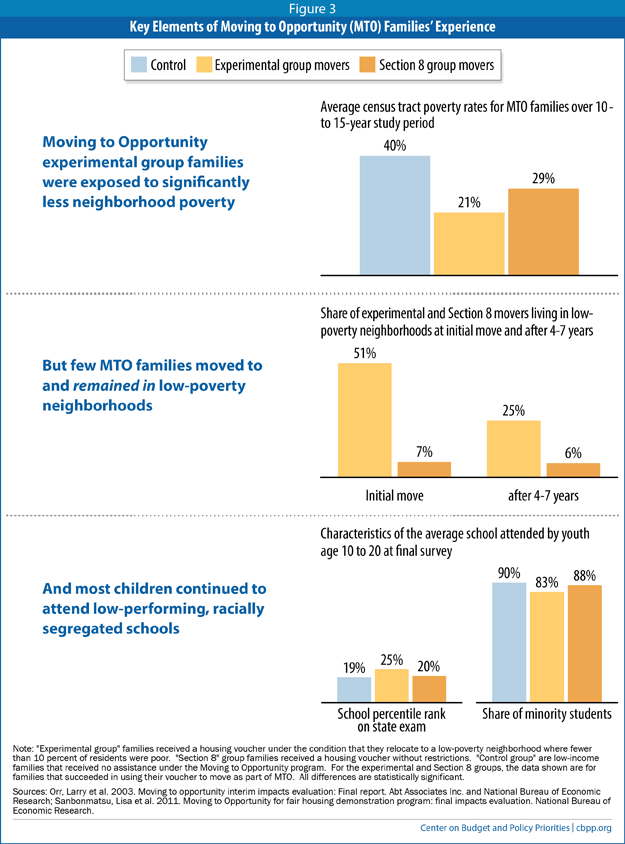

Initiated in 1994, the Moving to Opportunity demonstration was the first random-assignment study designed to test this thesis. Under MTO, volunteer low-income families living in public or private assisted housing in neighborhoods of extreme poverty were randomly assigned to one of three study groups. The families in the “experimental” group received housing vouchers under the condition that they use the voucher to move to a low-poverty neighborhood and remain there for at least one year. (MTO measured “low-poverty” as a census tract where fewer than 10 percent of residents were poor in 1990.) Families in the “Section 8” group received housing vouchers with no special conditions. Families in the “control” group received no assistance through MTO (though some received housing vouchers through regular waiting lists or because they were forced to relocate due to redevelopment of the properties in which they lived). Researchers tracked a broad range of economic, educational, social, and health outcomes for program participants over 15 years.

Moving to Opportunity produced three major findings:

- Housing vouchers enabled families to live in safer, lower-poverty neighborhoods, although only a small share of families in the MTO experimental and Section 8 groups actually located and remained in low-poverty neighborhoods for more than several years.

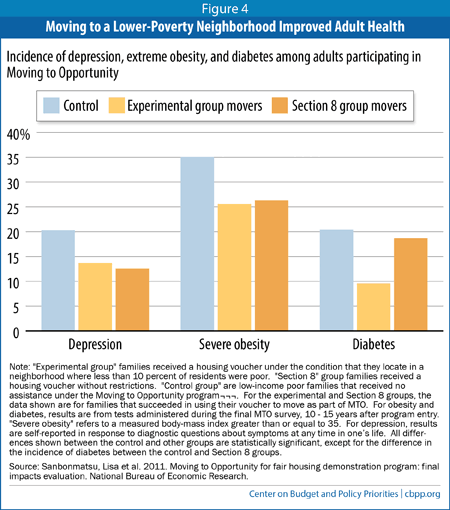

- Living in safer, lower-poverty neighborhoods yielded substantial mental and physical health benefits for girls and mothers. But there were negative mental health outcomes for boys, and researchers generally found no benefits among boys from MTO participation.

- Despite living in less disadvantaged neighborhoods, MTO families in the experimental and Section 8 groups generally did not experience economic gains for adults or educational gains for children.[20]

These findings, discussed in more detail below, are encouraging in some respects but disappointing in others. Yet the study has important limitations; for instance, few MTO experimental or Section 8 group families moved to and remained in low-poverty neighborhoods, and their children generally continued to attend low-performing, highly segregated schools. Follow-up research suggests that some of these limitations may have influenced key outcomes for children and adults, particularly the disappointing educational outcomes for children and mental health outcomes for boys.

Housing Vouchers Enabled MTO Families to Live in Lower-Poverty Neighborhoods With Less Crime

MTO participants were drawn from assisted housing (90 percent lived in public housing) located in highly segregated neighborhoods with very high poverty rates in five major cities. Poverty rates in these neighborhoods exceeded 50 percent, on average. Adult labor force participation rates and education levels were low. More than 90 percent of the residents in the neighborhoods were minorities.[21]

Using a housing voucher to relocate sharply reduced MTO families’ exposure to neighborhood poverty. One year after receiving a housing voucher, experimental group families who had moved were living in neighborhoods with average poverty rates of 15 percent — 35 percentage points lower than the neighborhoods where the control-group families were living. Five years into the study, the families in the experimental group that succeeded in moving were living in neighborhoods with average poverty rates of about 20 percent — half the 40 percent poverty rate in neighborhoods where the control-group participants resided.[22] Over time, the gap between the average neighborhood poverty rates for these groups continued to lessen, mostly because the average neighborhood poverty rates for control group participants declined to just over 30 percent at the 10-year point.[23] Nevertheless, over the entire 10- to 15-year period of the study, the average neighborhood poverty rate for experimental group families that moved was about half that for control group families — 21 percent versus 40 percent.[24]

While families in both the experimental and Section 8 groups that moved lived in neighborhoods that had lower poverty rates, on average, than the neighborhoods in which control group families resided, few of these families lived in neighborhoods with low poverty rates (i.e., below 10 percent) for very long. There appear to have been two reasons for this. First, some experimental group families that moved didn’t move into low-poverty neighborhoods, despite the restrictions attached to their voucher. This is because neighborhood poverty rates at the program’s start were measured using the 1990 Census, which didn’t accurately reflect current conditions in some declining neighborhoods during the latter half of the decade, when most families moved for the first time. Thus, 89 percent of the experimental group families that moved succeeded in using their vouchers to move initially to a unit in a low-poverty neighborhood, as defined by the 1990 Census, but only 39 percent of the neighborhoods to which these families moved still qualified as low poverty in the 2000 Census.[25]

Second, MTO required experimental group families to remain in the unit to which they initially moved for only a year, and many subsequently moved to higher-poverty neighborhoods.[26] Of the experimental group families that moved as part of MTO, only 27 percent were living in neighborhoods with poverty rates of less than 10 percent at the time of the interim study survey, which was conducted four to seven years after families’ entry into the program.[27]

In short, over the course of the study, MTO experimental vouchers generally helped families to move to and remain in neighborhoods of moderate poverty — where poverty rates ranged from 15 to 24 percent and were lower in general than the neighborhood poverty rates where these families had originally lived — but not to move to and remain in low-poverty neighborhoods.[28] (See Figure 2.)

Families’ exposure to crime also declined. Violent crime rates in the neighborhoods into which experimental group families initially moved were less than half the very high violent crime rates in the origin neighborhoods.[29] There was also a significant, though smaller, reduction in property crime rates in the new neighborhoods. These improvements were sustained over the full follow-up period. Consistent with declines in neighborhood violent crime rates, families in the experimental group also reported fewer observations of drug crime and reported feeling safer than families in the control group.[30]

Though control group families also moved over time to neighborhoods with lower incidences of violent and property crimes — or the neighborhoods in which they lived improved in these respects — significant differences in neighborhood crime rates remained after ten years. For example, the incidence of violent crime in control group neighborhoods was 24 percent higher at the ten-year point than in neighborhoods where experimental group families lived.[31]

The declines in neighborhood crime are impressive but perhaps not surprising. Escaping neighborhood violence and other crime was a major motivation for families to participate in MTO, according to interviews with participant families. The outcomes show that similarly motivated families — those in the control group — were far less successful in realizing their goal if they didn’t receive a housing voucher.

While the neighborhoods in which experimental group families lived had lower poverty and crime rates, on average, they differed little from the origin and control group neighborhoods in other important respects. For instance, the neighborhoods in which experimental group families lived remained highly racially segregated, did not (on average) have significantly higher levels of educational attainment among residents, and did not have much better-quality schools than the origin and control group neighborhoods.[32] (See Figure 3.) As discussed further below, follow-up research by Margery Austin Turner of the Urban Institute and others suggests that these factors affected outcomes for children and adults, particularly educational outcomes under MTO for children.

Girls Moving to Safer, Lower-Poverty Neighborhoods Under MTO Experienced Large Mental Health Gains, While Boys’ Mental Health Worsened

Moving from assisted housing developments in high-poverty neighborhoods to private housing in lower-poverty neighborhoods had strong positive effects on girls’ and adults’ mental health, as well as on adults’ physical health. Qualitative surveys of MTO participants indicate these gains were likely due to participants’ improved sense of safety and reduced exposure to crime and other sources of stress.

For girls in the MTO experimental group whose families moved to lower-poverty neighborhoods, there was a significant reduction in psychological distress compared with girls in the control group, a 51 percent reduction in the incidence of major depression, and a 54 percent reduction in the incidence of serious behavioral or emotional problems. (The incidence of these conditions or problems was measured over participants’ lifetimes to date, except for psychological distress, which was measured over the prior month.)[33] The authors of a follow-up study that found similar results noted that the increased risk for major depression among girls in the control group relative to the other groups is comparable to that found in research on sexual assault.[34]

Qualitative follow-up studies indicate that girls living in high-poverty neighborhoods face gender-specific threats: harassment, pressure for early sexual initiation, pervasive intimate-partner violence, and high risk of sexual assault.[35] In MTO, moving to lower-poverty neighborhoods appears to have provided girls with considerable relief from these threats, leading to the substantial mental health improvements noted above.[36]

The experience of boys participating in MTO was very different. For boys in the MTO experimental group, the risk of major depression (in the month prior to the survey) was twice that for boys in the control group, while the risks for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and conduct disorders were three times as high.[37] While the share of boys with these negative mental health effects is small, as is the share of girls with significant improvements in mental health, these findings are troubling.

Although researchers generally agree that girls in the MTO experimental group experienced mental health improvements because they felt safer and freer from sexual harassment and coercion in their new neighborhoods, the negative effects for boys are not well understood. Kessler et al.’s provocative description –– that experimental group boys’ increased risk for PTSD is similar to that found in studies of combat exposure in the military — suggests that some boys must have found lower-poverty neighborhoods to be a hostile and traumatic environment. Yet qualitative follow-up surveys provide only modest support for this, and some follow-up research points to alternative explanations.

Boys in both the experimental and control groups reported spending much of their leisure time in parks, schoolyards, vacant lots, street corners, and other public places. Experimental-group boys were more likely to complain that neighbors and police were intolerant of boys hanging out in public spaces. They reported that neighbors (both white and black) were quick to call the police on groups of boys, and they were more likely to report that police had questioned or harassed them.

Experimental group boys also were less likely than control group boys to maintain a meaningful relationship with their fathers or other father figures, perhaps because they lived farther away from their fathers and other male kin. Another factor that emerges from interviews with boys in the MTO experimental group is that they appear to be less skilled than control group boys in navigating neighborhood risks. In interviews, control group boys expressed more detailed knowledge of the geography of risks in their neighborhoods as well as strategies for avoiding troublesome corners or people. Some researchers hypothesize that as differences between the neighborhoods in which the experimental and control group families lived lessened over time (particularly as experimental group families moved back into poorer neighborhoods), experimental group boys may have been less selective in choosing friends — and may have been less well prepared to navigate the risks in their new neighborhoods, not having developed the relevant strategies that control group boys did growing up in high-poverty areas.[38]

Other research suggests that pre-existing vulnerabilities in families may explain part of the differential outcomes for boys in the MTO control and experimental groups. Analyzing data from the interim survey, Osypuk et al. found that the MTO experimental intervention was associated with a significant increase in the incidence of psychological distress and behavior problems among teenaged boys (12 to 19 years), in comparison with the control group, but only among boys in families with certain pre-identified vulnerabilities, such as living with a person with a disability or with a child with behavioral or learning problems.[39] The researchers hypothesized that neighborhood moves may be particularly stressful for youth in families with vulnerabilities, and that for boys, these stresses may have exacerbated the difficulties of adjusting to a new neighborhood.

In sum, the negative mental health outcomes for boys whose families initially moved to low-poverty neighborhoods under MTO are a reason for concern, but firm conclusions about the causes of these outcomes, as well as policy prescriptions, are difficult to draw.[40] Neighborhood change can be disruptive for a family, and the MTO evidence suggests that boys struggled to adapt to such changes more than girls.[41] At the same time, other research indicates that living in low-poverty neighborhoods is not harmful itself for low-income boys.[42] This suggests that efforts should be undertaken to ease the disruption that moving can cause; researchers Stefanie DeLuca, Greg J. Duncan, and their colleagues suggest that counseling to help parents and children transition to neighborhoods and schools, as part of an assisted housing mobility program, might improve outcomes for both boys and girls.[43] Such support, they suggest, might ameliorate the adjustment problems that some children may face. This would be a fruitful area to test, and upon which to conduct research.

Mothers Moving to Lower-Poverty Neighborhoods Experienced Significant Gains in Mental and Physical Health

Parental depression can negatively affect children’s well-being as well as be debilitating for the adults themselves. It is well documented that parental depression (and other stress-related problems, as explained above) can interfere with parenting and is associated with poor social development and poor physical, psychological, behavioral, and mental health for children, particularly young children.[44]

MTO Families Did Not Experience Economic Gains for Adults or Educational Gains for Children

Congress authorized the MTO demonstration in large part to provide a more rigorous test of impressive findings from the Gautreaux program, which was initiated in Chicago in the 1970s. Under Gautreaux, families either living in, or on the waiting list for, public housing were offered housing vouchers and the opportunity to move to available housing units that program staff had identified in neighborhoods where less than 30 percent of residents were African American. While families could refuse an offered unit, few did so, and participants were randomly assigned to housing locations, for all practical purposes. More than 7,000 families participated in the program, and researchers have collected data on participants for periods of more than 20 years.

Children and adults in Gautreaux families who moved to middle-income, mostly white suburbs appear to have experienced strikingly positive economic and educational gains, relative to those who remained in urban or higher-poverty neighborhoods. Researchers have been hesitant to draw firm conclusions from Gautreaux, however, despite its highly suggestive results. This is largely because the program was designed as a legal remedy to segregation, not as a true experimental study that randomly assigned families to treatment and control groups. The Gautreaux studies are thus “quasi-experimental,” making it difficult to be confident that neighborhood characteristics drove the relative outcomes.

MTO has added to the uncertainty. While the MTO outcomes were strong in some areas such as mental health, as discussed above, the economic outcomes for adults and educational outcomes for children did not replicate the Gautreaux findings. However, in light of the Gautreaux findings as well as separate research indicating that neighborhood characteristics do influence children’s cognitive development and school achievement, is it worth exploring some factors that may explain the MTO results.

Gautreaux Families Experienced Large and Long-Lasting Neighborhood Improvements That Appear to Have Benefited Children

About half of Gautreaux participants moved to middle-income, mostly white, suburbs of Chicago, while the other half moved to neighborhoods within the city. Midway through program implementation, neighborhood restrictions were loosened due to a shortage of available units that met the initial criteria; as a result, about one-fifth of Gautreaux participants landed in neighborhoods that were poor and segregated but designated as “improving” by program administrators (nearly all of these neighborhoods were in the city of Chicago).

Still, participants experienced significant reductions in neighborhood poverty rates: nearly half of Gautreaux participants moved to neighborhoods with poverty rates of less than 10 percent, and the mean poverty rate in destination neighborhoods was 17 percent, well below the 42 percent average in origin neighborhoods. Participants also experienced substantial changes in two other important respects: minority neighborhood concentration and distance from original neighborhoods. About half of Gautreaux families moved to neighborhoods where less than 10 percent of residents were African American, and the average concentration of African Americans in destination neighborhoods was 30 percent; at program entry, families lived in neighborhoods that were 83 percent African American, on average. For families that moved to the suburbs, their new neighborhoods were located an average of 25 miles from their original homes, a relatively long distance. In these respects, Gautreaux families experienced much greater neighborhood change than MTO families.

Children’s outcomes under Gautreaux were impressive. Those who moved to the suburbs attended better schools, were less likely to drop out before completing high school, received higher grades, and were more likely to attend college than those who remained in Chicago city neighborhoods. They also were more likely to be employed full time as adults, and to earn better wages, than those moving to locations within the city. [49]

Moving to Opportunity’s Disappointing Educational Results May Be Related to Study’s Limitations

In contrast, the MTO cognitive and educational outcomes for children were disappointing. MTO interim survey data (four to seven years after program entry) found significant and strong positive neighborhood effects on reading test scores in the two demonstration sites that had the highest initial levels of concentrated neighborhood disadvantage: Chicago and Baltimore.[50] But evidence of these effects vanished in the long-term (10- to 15-year) data, which showed no detectable differences in educational achievement among children in the experimental, Section 8, and control groups, even for children who were pre-school age at program entry.[51]

A straightforward reading of the MTO data thus implies that moving to a lower-poverty neighborhood has no lasting impact on cognitive or educational outcomes for children. Yet there are good reasons to resist this conclusion. First, it runs counter not only to Gautreaux but also to the studies by Sampson and Sharkey as well as the research on toxic stress discussed above, which imply that moving out of neighborhoods of extreme poverty should benefit children’s cognitive development.

Second, for all of its strengths, MTO was a weak experimental intervention in important respects.[52] As explained above, not only did few MTO experimental group families live in truly low-poverty neighborhoods for a significant length of time, but the rates of neighborhood poverty and violent crime to which control group families were exposed also declined markedly over time, diminishing the contrast between the experiences of the two groups.[53]

It therefore is possible that the convergence between the MTO experimental and control groups’ exposure to neighborhood poverty and crime blunted the demonstration’s findings on educational outcomes over time. This explanation would appear to be consistent with the findings that there were significant improvements in reading scores among black children in the MTO experimental group, compared with the control group, in the interim analysis of data from Chicago and Baltimore, but that these impacts vanished between the interim and final survey.[54] The original neighborhoods of MTO participants at these two sites were significantly more segregated, disadvantaged, and dangerous than those at the remaining three MTO sites.[55] Consistent with the research by Sampson and Sharkey, one would expect that children moving out of such neighborhoods would be most likely to benefit from the moves. Yet, by the time of the final MTO survey, most control group families also had moved out of their original neighborhoods and had been living in lower-poverty neighborhoods for at least five years.[56]

The MTO intervention also was weak in a second, critical respect — school quality. Children in the MTO experimental group whose families moved with a voucher typically attended low-performing schools that were only slightly less poor and segregated than those attended by children in the control group. For example, in the average school that children in the experimental group attended over the duration of the study, 83 percent of students were minority (compared with 90 percent for children in the control group), 67 percent of students were eligible for free or reduced-price meals (75 percent for the control group), and student scores on state exams ranked the school at the 25th percentile (19th percentile for the control group).[57] (See Figure 3.) In comparison to Gautreaux, MTO’s outcomes for children’s educational achievement may have been disappointing, therefore, because the neighborhoods into which children in the experimental group moved were insufficiently improved with respect to the characteristics — such as school quality — that matter most.

A re-analysis of the MTO data by Urban Institute researcher Marjory Austin Turner and others supports the hypothesis that MTO failed to confirm the Gautreaux results not because the latter were fundamentally flawed, but because of the different characteristics of the comparison neighborhoods that MTO tested. In re-analyzing the MTO data, Turner et al. compared outcomes for children using a measure of each household’s exposure to “high-opportunity” neighborhoods, rather than by comparing outcomes for children across the experimental, Section 8, and control groups.[58] They found that the longer children in MTO families lived in high-opportunity neighborhoods — defined as neighborhoods where poverty rates were less than 15 percent, labor force participation rates exceeded 60 percent, and more than 20 percent of adults completed college — the higher their reading and math scores. These outcomes held for both boys and girls.

Box 3: Questions About Adult Self-Sufficiency Remain After Relocation

The positive employment outcomes for adults who participated in the Gautreaux program in Chicago played a role in spurring Congress to authorize the Moving to Opportunity (MTO) demonstration.a But the very different results from the two initiatives leave continuing uncertainty about the possible linkages between the types of neighborhoods families live in and how much they work and earn.

Early Gautreaux studies found significantly higher employment rates among adults who moved to suburban locations compared with those who remained in the city.b Longer-term studies also found improvements for Gautreaux adults, although these gains were concentrated among families that had moved to low-poverty neighborhoods with minority concentrations of less than 10 percent (irrespective of whether the neighborhoods were located in suburban or city areas).c

Yet MTO found no significant differences in employment, earnings, or welfare receipt among the experimental, Section 8, and control groups. (Under the demonstration, families in the “experimental” group received housing vouchers under the condition that they use the voucher to move to a low-poverty neighborhood and remain there for at least one year, while families in the “Section 8” group received housing vouchers with no special conditions, and the “control” group received no assistance through MTO.) Although adults in the experimental and Section 8 groups experienced substantial increases in employment and earnings during the 15-year study period, control group adults made equivalent gains. These findings were particularly surprising in light of substantial improvements in physical and mental health among adults in the MTO experimental group: rates of obesity and diabetes — which can hinder ability to work — fell by about 40 percent; the magnitude of those changes is similar to that found in the best-practice pharmaceutical and lifestyle interventions.d (See Figure 4.)

Researchers have offered various possible explanations for the different employment-related outcomes in Gautreaux and MTO. For example, powerful social and economic changes, including changes in welfare policy that emphasized work, a major expansion of the Earned Income Tax Credit, and a booming economy in the late 1990s that resulted in historically low unemployment rates, occurred during the MTO study period. These changes may have overwhelmed the potential effects of neighborhood characteristics on MTO families.e Others have suggested that the different types of neighborhood changes effected in Gautreaux and MTO — specifically, while many Gautreaux families moved to mostly white, middle-class, suburban neighborhoods, families in the MTO experimental group typically lived after the initial year or so in poorer urban neighborhoods with large minority concentrations — might help explain the differences in “self-sufficiency” outcomes.f

MTO researchers also uncovered evidence that casts doubt on some, though not all, of the explanatory hypotheses connecting neighborhoods and employment. For instance, MTO researchers found no evidence that living in lower-poverty neighborhoods improved families’ access to or information about jobs.g In addition, researchers found that limited availability of public transportation in low-poverty neighborhoods was a particular challenge for families in the MTO experimental group, most of whom did not own or have access to a car to help them get to work.h Families that had access to a car were more likely both to work andto remain in low-poverty areas.i

a Popkin, Rosenbaum & Meaden (1993); DeLuca et al. (2010).

b Rosenbaum (1995).

c DeLuca et al. (2010).

d Sanbonmatsu et al, 2011, Ludwig, 2012, Gennetian et al, 2013.

e DeLuca et al. (2012); Orr et al. (2003).

f Clampet-Lundquist & Massey (2008); Turner et al. (2012).

g DeLuca et al. (2012); Turner et al. (2012).

h DeLuca et al. (2010).

i Pendall et al. (2014).

j Kling et al. (2007), Gennetian et al. (2013).

Rigorous Study Provides Evidence That High-Opportunity Neighborhoods Improve Children’s Educational Achievement

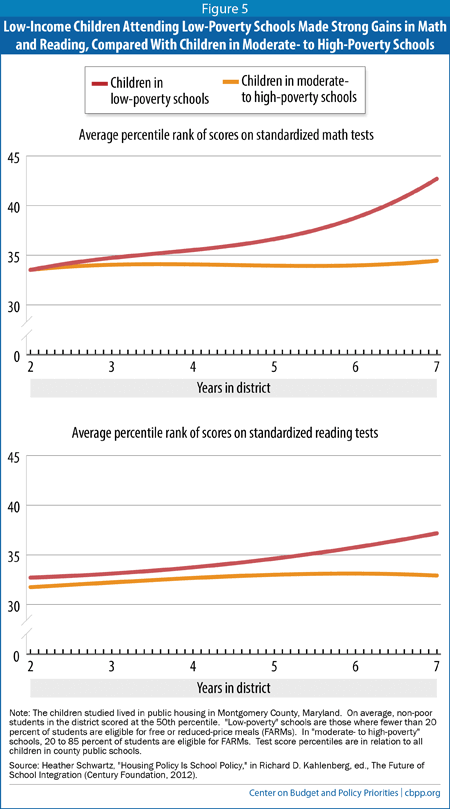

An important recent study by RAND Corporation researcher Heather Schwartz has independently bolstered the case for Gautreaux’s conclusion that low-poverty, high-opportunity neighborhoods can improve children’s educational achievement. In her study of low-income children living in public housing and attending elementary schools in Montgomery County (a Maryland suburb bordering the District of Columbia),[59] she found that:

- Low-income students who lived in low-poverty neighborhoods and attended low-poverty schools made large gains in reading and math scores over a period of seven years, compared with students attending moderate- or moderately high-poverty schools.

- These educational gains accrued over time, with the majority of the gains accruing in years five to seven. Residential stability in low-poverty neighborhoods and schools thus appeared to be a crucial condition of the children’s success.

- Students benefitted academically from living in low-poverty neighborhoods, but most (two-thirds) of the gains came from attending a low-poverty school.

Schwartz tracked 850 students in the county, 72 percent of whom were African American, 16 percent Hispanic, and the rest either non-Hispanic white or Asian. The students’ families had average incomes of about $22,000 per year as of 2007. In their initial year in the school district, the students’ math and reading scores were well below the average for students in the school district.[60]

Schwartz’s study took advantage of a natural experiment made possible by the county’s housing policies. Applicants for public housing assistance were randomly assigned to public housing developments across the county. Because of the county’s zoning policies, most of these developments are located in low-poverty neighborhoods (with poverty rates of less than 10 percent), while the others are located in neighborhoods with moderate or high poverty rates (up to 32 percent). This enabled Schwartz to compare educational outcomes for students living in neighborhoods and attending schools that differed significantly with respect to poverty and related characteristics. Housing location was remarkably stable for these families, and Schwartz tracked students over a seven-year period.

Schwartz’s results were striking: at the end of seven years, the test scores of the public housing children in low-poverty schools had risen by 8 percentile points in math and 4 percentile points in reading, thereby closing half of the achievement gap between those students and non-poor students in the district in math and one-third of the gap in reading. (See Figure 5.) Those are large gains by educational standards. The gains were greatest among the students in neighborhoods where poverty rates were very low — less than 5 percent. By contrast, over the same period, there were no significant improvements in the results for public housing students in the moderate- and moderately high-poverty schools.[61]

The improvements were even more pronounced when Schwartz compared outcomes for children using the school district’s own criteria for distinguishing advantaged and disadvantaged schools, rather than distinguishing among schools based on family income alone.[62] After seven years, poor students attending advantaged schools performed 9 percentile points higher in math and 7 percentile points higher in reading than their peers in disadvantaged schools. These results are striking in light of the fact that the disadvantaged schools in Montgomery County receive substantial additional resources through state-of-the-art educational intervention programs. Yet the benefits of attending advantaged schools swamped the effects of the educational interventions in disadvantaged schools.

The length of time required for these gains to become evident is also notable. During the first several years of the study, the average test scores of the students in both low-poverty and advantaged schools differed little from those in other schools; significant differences began to appear only in the students’ fifth year. The differences widened considerably in the sixth and seventh years, as test scores of students in low-poverty and advantaged schools improved significantly. In general, this is consistent with the Gautreaux findings, where children struggled initially as they adjusted to new neighborhood and school environments that differed significantly from their original environments, yet achieved significant educational gains in the longer run. These results are also consistent with the picture portrayed by Turner et al.’s reanalysis of MTO data, which showed that the longer children remained in low-poverty, high-opportunity neighborhoods, the better their school performance.

Neighborhood and school characteristics are interdependent — for instance, the income and level of educational attainment of neighborhood residents strongly influence the peer groups to which students are exposed in schools — making it difficult for researchers to tease apart the relative influence of each. Schwartz attempted to do so, however, finding that both neighborhood and school poverty influenced student test scores and that the magnitude of the effect of school poverty was about twice as large as that of neighborhood poverty.[63] The benefits of living in low-poverty areas for students were most significant in neighborhoods with poverty rates of less than 5 percent. These findings are consistent with the results of other studies that compare the relative influence of school quality and other neighborhood characteristics, although it should be noted that the variation in neighborhood poverty rates in Montgomery County is relatively small.[64]

Conclusion

The body of research is complex but careful consideration of the evidence supports the conclusion that neighborhoods affect children’s well-being, both in the short and long term. First, there is growing evidence that violent, stressful, high-poverty neighborhoods can compromise children’s cognitive development, school performance, and health. Second, while MTO did not affirm the Gautreaux studies’ conclusions that moving from high-poverty to low-poverty neighborhoods yields economic gains for adults and improved scholastic achievement for children, researchers have identified limitations in the MTO intervention that may explain these inconsistent results, at least the educational outcomes for children. With this in mind, a balanced consideration of the full body of evidence — one that takes into account Heather Schwartz’s rigorous study of children in Montgomery County, as well as Gautreaux and MTO — indicates that low-poverty neighborhoods with high-quality schools improve children’s school performance.

These conclusions have implications for housing policy. Federal rental assistance programs fall short in helping families live in neighborhoods that provide better opportunities, as the next section of this paper explains. The final section of the paper discusses possible policy reforms to help address these issues.

End notes:

[1] Ellen & Turner (1997), Turner & Kaye (2006), Jargowsky & El Komi (2009), DeLuca & Dayton (2009), Burdick-Will et al. (2011).

[2] Jencks & Mayer (1990), Ellen & Turner (1997), Sampson, Raudenbush, & Earls (1997), Sampson et al. (2002), and Sampson (2012). These sources are cited in Ludwig et al. (2013).

[3] Kawachi & Berkman (2003), Turner & Kaye (2006), Berube (2008).

[4] Ellen and Turner (1997), Galster (2012).

[5] Schwartz (2010).

[6] The roles of violence and stress are discussed below, and environmental hazards — particularly those associated with the lower-quality housing typically found in poorer neighborhoods — will be discussed separately in a forthcoming Center report. Generally, children in high-poverty neighborhoods are more likely to be exposed to health hazards such as lead-based paint, vermin, and pollution, and, as a result, are more likely to suffer from asthma and the serious effects of lead poisoning. These risks are cited in Berube (2008) and Cohen (2011), and explored in Kawachi and Berkman (2003).

[7] See Kahlenberg (2012) and Gallagher, Zhang, & Comey (2013) for reviews of literature linking these characteristics to low-poverty, high-quality schools.

[8] Aud et al. (2010), cited in Schwartz et al. (2012).

[9] Sampson et al. (2008). A separate study of Chicago youth by Ludwig et al. (2009), which took advantage of a natural experiment created by the random assignment of housing vouchers to families who had applied for vouchers, found similar results. This study, in discussion draft form, is discussed in Burdick-Will et al. (2011).

[10] Building on the work of Sampon and others, Wodtke et al. (2011) also found that sustained exposure to neighborhoods of concentrated disadvantage had a long-term impact on children’s educational achievement. Analyzing data, including neighborhood changes, for more than 4,000 students from across the country over a 17-year period, they found a 20 percentage-point difference in high-school graduation rates for black children with the greatest exposure to neighborhood disadvantage, relative to comparable black children with the least exposure.

[11] Sharkey (2010), Sharkey et al. (2012), and Sharkey et al. (2014).

[12] Sharkey et al. (2012).

[13] Sharkey et al. (2014).

[14] Sharkey et al. (2014), p. 217.

[15] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2014).

[16] National Scientific Council on the Developing Child (2014); National Scientific Council on the Developing Child (2010); Shonkoff et al. (2009); Shonkoff et al. (2012).

[17] NSCDC (2009). Recent research showing that neighborhood poverty has a significant effect on the incidence of depression among low-income parents is discussed below.

[18] Aizer, Stroud, & Buka (2012).

[19] American Academy of Pediatrics (2012).

[20] Sanbonmatsu et al. (2011), “Forward.”

[21] Sanbonmatsu et al. 2011, Exhibit 2.1. Neighborhood characteristics were measured at the census tract level.

[22] Ludwig (2012). Only 47 percent of families assigned to the experimental group and 62 percent of those assigned to the Section 8 group succeeded in using their vouchers to move. This experience on the part of the Section 8 group families is roughly consistent with that of other families using housing vouchers. The reduced success rate of experimental group families was almost certainly due in large part to the requirement that they move to low-poverty neighborhoods, which presents additional challenges discussed in Section 3.

In most of our discussion of MTO, we focus on “treatment-on-treated” effects — that is, on the outcomes for those families in the experimental and Section 8 groups that actually moved with their vouchers (which in the case of the experimental group required an initial move to a low-poverty neighborhood) — as we are largely interested in understanding the effects of neighborhood conditions on families, rather than the effects of voucher issuance. But it’s worth noting that the “intent-to-treat” (ITT) impacts (that is, the impacts on families whether or not they succeeded in using the voucher they received as part of the demonstration to move to a new neighborhood (which, in the case of experimental group families, was required to be a low-poverty neighborhood) also were significant.

[23] Neighborhood poverty rates for control group families fell both as families moved out of their original assisted housing units and as neighborhoods surrounding those units improved over time. By the mid-2000s, the average poverty rate in MTO families’ original neighborhoods had fallen from 53 percent to 42 percent. See Sanbonmatsu et al. 2011, Exhibit 2.1.

[24] Ludwig 2012, Ex. 2. Results for Section 8 movers were roughly similar to those for experimental-group families that moved, though the improvements (relative to the control group) were smaller in magnitude. The average neighborhood poverty rate over the entire 10- to 15-year study period was 28.5 percent for families in the Section 8 group that moved, compared with 40 percent for the control group. Note that these outcomes differ from those of Housing Choice Voucher users overall, as discussed in Section 2 of this paper.

[25] Orr et al. (2003); also discussed in Comey, Briggs, & Weismann (2008). Families that enrolled in MTO leased up over a five-year period from 1994 to 1999. Using a linear interpolation, researchers have estimated that only about half of the experimental group families that moved were located in low-poverty neighborhoods at initial lease-up. It is not clear why 11 percent of experimental group families were allowed to move initially to neighborhoods with poverty rates that exceeded 10 percent in 1990.

[26] MTO experimental group families that made an initial move remained at their initial addresses just three years, on average, and three-quarters of these families had moved again within five years of their initial move. Sanbonmatsu et al. (2006). See Turner et al. (2012) for a discussion of the neighborhood trajectories of families over time.

[27] Ludwig (2012), Exhibit 2, and Orr et al. (2003). To make for consistent comparisons, all figures related to area poverty rates are based on the 2000 Census.

[28] In addition, mobility among some control group families may have reduced the magnitude of the neighborhood differences experienced by families in the three groups. By the time of the interim survey (four to seven years out from program assignment), 70 percent of control group families had moved from their original locations, including many who were compelled to move from their original public housing units by HOPE VI demolitions. (About one-fifth of all MTO participants originally lived in public housing units that were later demolished under HOPE VI.) Many control group families displaced by HOPE VI demolitions would then have received a Section 8 voucher. See DeLuca et al. (2012).

[29] In a baseline survey of Boston families participating in the MTO demonstration, for example, one-fourth reported that someone in the household had been assaulted, beaten, stabbed, or shot within the past six months, and another quarter reported that someone had tried to break into their house, or that a household member had been threatened with a knife or gun or had their purse or jewelry snatched, in the past six months. See Kling, Liebman, & Katz (2005), cited in DeLuca et al. (2012).

[30] Crime rates in neighborhoods where families in the Section 8 group located were also lower than crime rates in neighborhoods where control group families lived, though not as low as the average crime rates for neighborhoods into which experimental group families moved.

[31] Ludwig (2012).

[32] Ludwig (2012), Turner et al. (2012), DeLuca et al. (2012).

[33] Sanbonmatsu et al 2011, Exhibits 4.4, 4.5, and 4.6. Sanbonmatsu et al. also found reductions in psychological distress and depression among girls in the Section 8 group whose families had moved, but these were not statistically significant. At the time of the final MTO study survey, these girls were aged 13 to 20 years old; at program entry, they were 0 to 11 years old, and their average age was 4.7 years. Except where noted, the figures are for long-term outcomes under MTO – that is, during the 10- to 15-year follow-up period and represent the results for the “treatment-on-treated” group, as these provide the best measure of the effects of neighborhood conditions. Researchers assessed “psychological distress” using the Kessler 6 measure, and the measured reduction for girls in the experimental group whose families moved was equivalent to one-quarter of a standard deviation. Results for some other measures of mental health also were positive for girls but not statistically significant. Similarly, the results for girls in families using regular Section 8 vouchers suggested improvements in some areas of mental health but were not large enough to be statistically significant.