At a point in time, there are about 2.2 million uninsured adults with incomes below the poverty line who lack a pathway to affordable health coverage because their states have refused to adopt the Affordable Care Act (ACA)’s Medicaid expansion.[1] But this group isn’t fixed, and over the course of the year — and over several years — the coverage gap affects a much larger number of people.

People in the coverage gap are ineligible for Medicaid because their states haven’t adopted the expansion and they have incomes too low to qualify for ACA marketplace subsidies. While we estimate that 2.2 million uninsured adults were in the coverage gap in 2019, this estimate is based on people’s answers to questions about total income over the prior year and health coverage at a single point in time.[2] Many more adults transition into and out of the coverage gap over the course of a year, given high rates of income volatility among households with low incomes and frequent coverage loss among low-income people. This means that over the full course of 2019, it’s likely that many more people were in the coverage gap than the 2.2 million commonly cited as a snapshot estimate. And, over the course of several years, the number of people in the coverage gap is even higher, as some people see their incomes fall or they lose their health insurance from one year to the next. Permanently closing the coverage gap would provide a pathway to affordable health insurance for millions of people with low incomes, allowing them to avoid coverage loss and maintain stable access to health care.

While data limitations do not allow for precise estimates of coverage gap transitions, research demonstrates marked income instability among households with low incomes, even prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, that make transitions into and out of the coverage gap more likely. Because eligibility for Medicaid and ACA marketplace financial assistance is tied to income, fluctuations in income increase the chance of fluctuations in eligibility.

For adults in states that haven’t adopted the ACA’s Medicaid expansion, income fluctuations from above the poverty line to below it can mean the loss of health coverage; when a person’s income is above the poverty line, they qualify for subsidized coverage in the ACA marketplace, but when their income falls below the poverty line, they transition into the coverage gap. Similarly, in non-expansion states, a person with employer coverage can fall into the coverage gap if they lose their job and the health care that comes with it and their income falls below the poverty line. By contrast, in states that have adopted Medicaid expansion, when a person’s income goes from above to below the poverty line, they can switch from marketplace coverage to Medicaid, though many still lose coverage due to difficulty navigating these transitions. And in states that have adopted expansion, when someone loses a job and employer-sponsored coverage, they can qualify for Medicaid, as well. Because incomes often fluctuate during the year, the total number of people in the coverage gap over the course of the year is significantly larger than the number in the gap at a point in time.

Research shows that large numbers of people see their incomes fluctuate substantially. In a one-year period, households with low and moderate incomes typically experienced more than five months when their income fluctuated by more than 25 percent above or below their average monthly income, one study found.[3] Other data show that more than 1 in 3 households with children lost one-fourth or more of their annual cash income in either 2015 or 2016.[4]

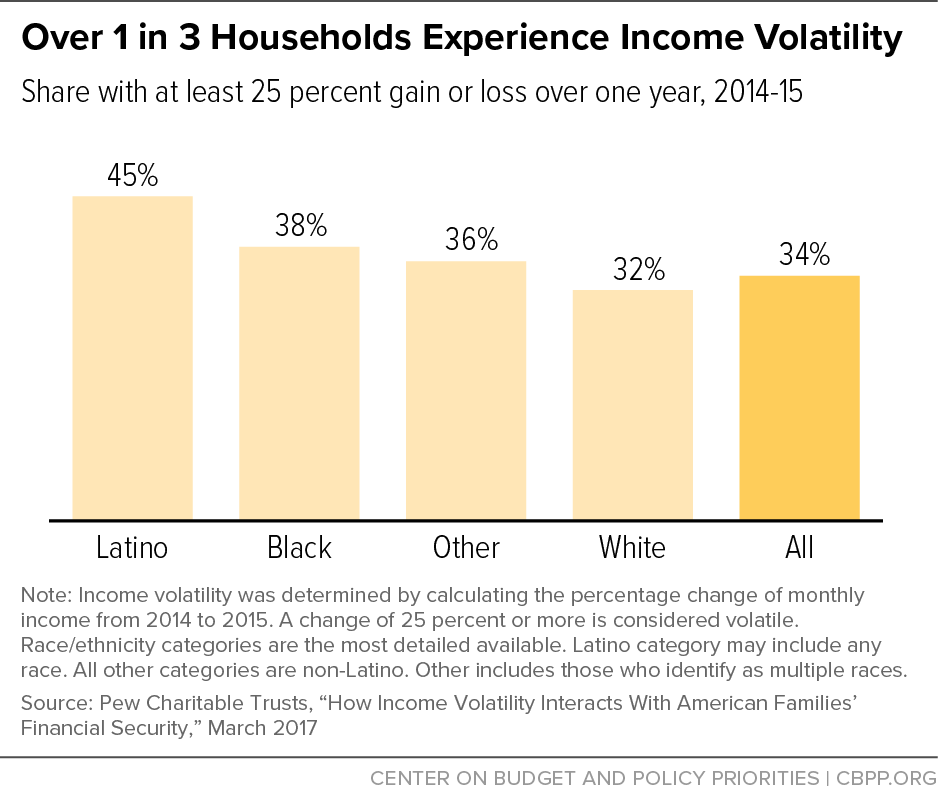

A 2015 survey from the Pew Charitable Trusts found that 34 percent of households experienced income volatility, defined by Pew as a year-over-year change in annual income of 25 percent or more. The rate was especially high among households with low incomes, 53 percent of whom experienced income volatility, compared to 27 percent for middle- and upper-income households.[5] Income volatility was also more prevalent among Black and Latino households, with 38 percent and 45 percent reporting volatility, respectively.[6] (See Figure 1.) Moreover, Black and Latino households experienced larger median losses of income per episode of negative income volatility than the average household.[7]

Changes in insurance coverage — and loss of coverage — are frequent among low-income adults. One survey of low-income, non-elderly adults in three states found that nearly one-quarter of respondents saw a change in their insurance coverage in the prior 12 months: either losing, gaining, or switching insurance plans.[8] Over half of those whose insurance coverage changed experienced at least one period in which they were uninsured.

Adults in non-expansion states may become uninsured and land in the coverage gap for many reasons, including losing eligibility for marketplace subsidies due to declines in income, losing employer-sponsored insurance due to job loss, losing Medicaid or marketplace eligibility for administrative reasons even when they remain eligible, or losing Medicaid due to changes in marital status or other family circumstances affecting eligibility.

Data from the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS) show that over the 12-month period ending December 2018, 19 percent of low-income, non-elderly adults who were insured at some point during that period lost coverage and became uninsured.[9] This coverage loss may include transitions into the coverage gap for adults in non-expansion states.

For parents with low incomes in non-expansion states, small gains in income can trigger coverage loss and transitions into the coverage gap.

Adults may qualify for Medicaid through several pathways — including income, disability, and pregnancy — and for all pathways periods of coverage loss are significant.[10] Unlike adults without children, who aren’t eligible based on income for Medicaid in non-expansion states regardless of how low their incomes are, parents may be eligible based on income — but only if their incomes are very low. The median non-expansion state caps Medicaid eligibility for parents at about 40 percent of the poverty line, or just $8,800 in yearly income for a single parent with two children. In Texas, the state with the most people (766,000) in the coverage gap in 2019, parents can make no more than 17 percent of the poverty line (only $3,733 annually) to remain eligible for Medicaid.[11]

With income thresholds for parents so low in non-expansion states, it takes only a slight bump in income for parents to lose Medicaid eligibility and fall into the coverage gap. For parents already struggling with very low incomes, a small increase in wages or hours worked means they may lose Medicaid coverage because their state has not adopted the expansion; it also means they won’t qualify for any form of federal assistance for health insurance if their income rises but remains below the poverty line.

Research shows that adults who lose Medicaid coverage experience decreases in access to health care. Adults with more unstable Medicaid coverage decreased their use of prescription medications by 19 percent, and saw increases in their use of emergency rooms, hospitalizations, and office visits by between 10 and 36 percent, compared to individuals with consistent Medicaid coverage.[12] MEPS data show that non-elderly adults with Medicaid who became uninsured over the course of the year were more than twice as likely to report being unable to get medical care or prescription medication as those with Medicaid who did not become uninsured.[13]

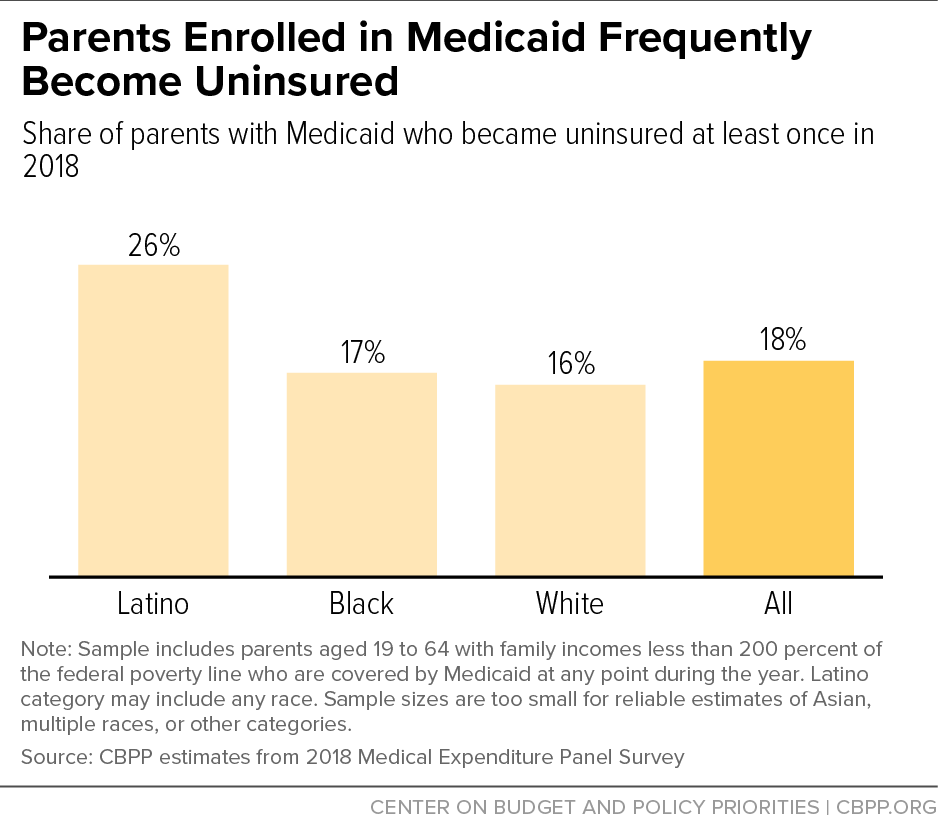

Over the 12-month period ending in December 2018, data from MEPS show that 18 percent of low-income, non-elderly parents enrolled in Medicaid lost coverage and became uninsured.[14] (See Figure 2.) Unfortunately, these data are not available by state, so we cannot separately measure loss of Medicaid in non-expansion states. But for parents in non-expansion states whose income falls below the poverty line, coverage loss can occur when incomes rise very modestly such that parents have too much income to qualify for Medicaid but not enough income to qualify for coverage through the marketplace.

Medicaid coverage loss was particularly common among Latino parents. In 2018, among all states, 26 percent of low-income, non-elderly Latino parents enrolled in Medicaid lost coverage and became uninsured. This means that Latino people are not only disproportionately in the coverage gap at a point in time,[15] but Latino parents also face more disruptions in Medicaid coverage over time, at least nationally (these MEPS data are also unavailable by state). Several studies examining earlier periods have also found high rates of coverage loss among Latino people.[16] The reasons for this pattern are uncertain but could include higher rates of income volatility or administrative obstacles such as complex renewal policies.[17]

While these data focus on a single-year timeframe, the share of people experiencing coverage loss over multiple years would be even larger. For example, from 2014 to 2016, 43 percent of households with children included at least one person who had no health coverage. In comparison, the one-year rate of households with children that included at least one person with no health coverage was 25 percent.[18]

Closing the coverage gap would not only provide a pathway to affordable coverage for the millions of adults who are caught in the gap at a point in time, it would also help protect against the harmful effects of Medicaid coverage disruption and provide health coverage for the many more uninsured adults who transition into and out of the coverage gap over the course of a year or several years.