The latest proposal to repeal the Affordable Care Act (ACA) — released June 19 by a group of prominent conservatives and conservative organizations — would have similar harmful impacts on health insurance coverage, access to care, health, and financial security as last year’s repeal bills.[1] Modeled on legislation that Senators Bill Cassidy, Lindsey Graham, Dean Heller, and Ron Johnson proposed last September (“Cassidy-Graham”), the new plan would:

- eliminate the ACA’s expansion of Medicaid to low-income adults and its subsidies that help moderate-income consumers afford individual market coverage, replacing them with a flawed and inadequate block grant to states;

- severely disrupt the individual market for health insurance, potentially causing markets in some states to collapse; and

- end critical ACA protections for people with pre-existing conditions, including the requirement that plans cover essential health benefits, such as mental health and substance use treatment, prescription drugs, and maternity care.

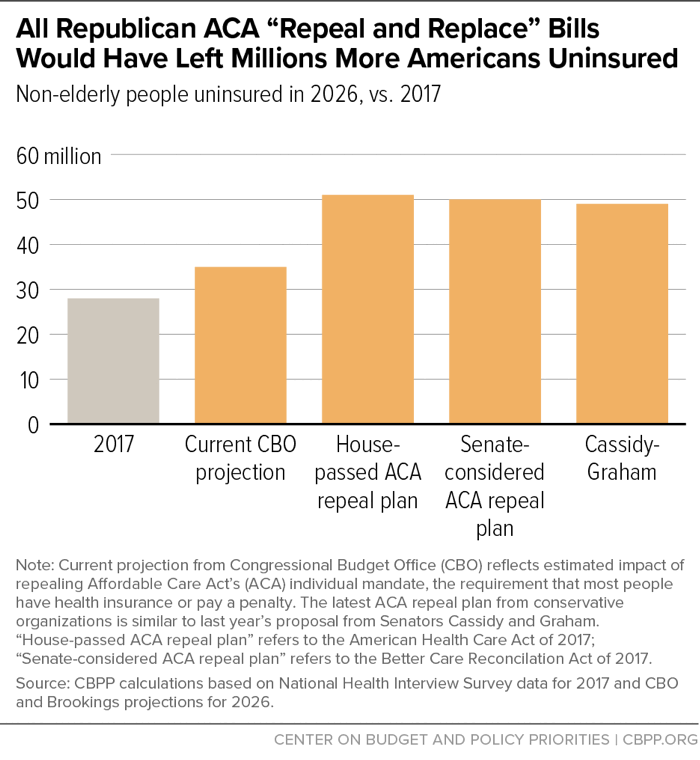

The new plan provides limited detail, failing to specify, for example, the total funding levels for the proposed block grant or how funding would be allocated across states. Nonetheless, given its similarity to Cassidy-Graham, it is clear the new plan would have similar harmful impacts on coverage, access to care, and health as that earlier proposal, which experts projected would have caused about 21 million people to lose coverage.[2] That would have resulted in a non-elderly uninsured rate of about 18 percent — almost 50 million people — in 2026, a large increase from 2017’s rate of 10.7 percent, or about 29 million people.[3] If anything, the new proposal — coupled with the repeal of the individual mandate already enacted by Congress last year — would likely result in a higher uninsured rate than the earlier bill, since it appears to provide less federal funding for coverage.

The new proposal comes on the heels of the Administration’s decision not to defend the ACA against a lawsuit from state attorneys general, instead asking the courts to eliminate the ACA’s protections for people with pre-existing conditions, and it was released the same day the Administration finalized rules that will expand the availability of plans exempt from many ACA consumer protections.[4] Together, the new plan and the Administration’s actions show that, despite last year’s congressional rejection of ACA repeal, eliminating the ACA’s core provisions remains at the top of the Administration’s and many leading conservatives’ agenda.

Today, about 12 million people in 31 states and the District of Columbia are covered as a result of the ACA’s expansion of Medicaid to low-income adults, and about 10 million people across all states get help paying for individual market coverage from the ACA’s premium tax credits and cost-sharing reductions.[5] The new repeal plan would completely eliminate these programs.

It would replace them with a state block grant. As discussed below, while not specified in the proposal, total funding for the block grant would likely fall below the already inadequate levels proposed in last year’s Cassidy-Graham bill. But the block grant also suffers from severe structural flaws that would prevent it from replacing the coverage provided through Medicaid expansion and the ACA’s individual market subsidies, even if funding levels were higher.

-

States could not realistically use block grant funding to continue current coverage programs or create similar programs, because the financial risk would be too great. Under the proposal, a state that tried to use block grant dollars to offer Medicaid-like coverage or ACA-like subsidies that keep pace with health insurance premiums would expose itself to massive financial risk. Unlike current-law federal funding for Medicaid expansion and ACA subsidies, block grant amounts would not adjust for enrollment increases due to recessions or for higher costs due to public health emergencies, new breakthrough treatments, demographic changes, or other cost pressures — leaving states on the hook for 100 percent of those costs. The plan sponsors tout this cost shift to states as a benefit, noting that the plan eliminates “open-ended subsidies.”

To manage the resulting risk, states would likely avoid creating programs that guarantee coverage or robust financial assistance based on need. Instead, they might do one or more of the following: cap enrollment; offer very limited benefits; charge unaffordable premiums, deductibles, or copayments; limit assistance to fixed dollar amounts that would put coverage out of reach for most low- and moderate-income people; or redirect federal funding from providing coverage to other purposes, like reimbursing hospitals for uncompensated care.

-

Cuts would be much larger in the states that have done the most to expand coverage. Like Cassidy-Graham, the new proposal would base the initial allocation of state grants on current federal funding, but “over time, the grant would be based on a state’s number of low-income residents.” This approach penalizes states that have adopted Medicaid expansion or were more successful at enrolling eligible low- and moderate-income people in subsidized individual market coverage under the ACA, because such states have a higher ratio of people currently enrolled in ACA-funded coverage programs to low-income residents. As a result, the proposed formula would leave the states that are likely the most motivated to maintain current coverage levels with the least resources to do so. It would also penalize states with particularly high per-person health care costs, which similarly have high ratios of federal funding to low-income residents.

Nearly all current Medicaid expansion states have above-average ratios of current spending to low-income residents, putting them at risk for especially deep cuts under the new plan. States that would have seen especially deep cuts under Cassidy-Graham, with its similar funding formula, include Alaska, California, Connecticut, Delaware, the District of Columbia, Hawaii, Kentucky, Louisiana, Maryland, Massachusetts, Minnesota, Montana, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, North Dakota, Oregon, Rhode Island, Vermont, and Washington.[6]

- States could no longer obtain additional federal funding to expand coverage. Under current law, additional states that choose to take up the ACA’s Medicaid expansion — as Maine voters opted to do last year, as Virginia policymakers just opted to do, and as Utah, Idaho, and Nebraska voters may decide to do this fall — can automatically draw down federal funding to do so. Likewise, states that take action to increase ACA marketplace enrollment — for example, by investing state funds in outreach or adopting a state individual mandate — can automatically draw down additional federal funding for subsidies. By replacing these programs with a block grant, with capped total federal funding, the latest repeal plan would make federal funding for coverage a zero-sum game, where any additional funding for one state comes at the expense of other states.

- States would be free to spend resources in ways that would be less effective (or entirely ineffective) in providing coverage. Like the earlier Cassidy-Graham bill, the new proposal includes few guardrails to prevent states from using federal block grant funding to supplant current state funding for health programs, such as state programs that provide substance abuse and mental health services or fund public hospitals and other safety net providers. As the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) noted in its analysis of the earlier bill, states would be free to use block grant dollars to “fund some of their programs that would have operated under current law,” and some states, especially those that chose not to expand Medicaid, would likely do so.[7] Using federal funds to replace state funding for existing health programs would do nothing to mitigate the coverage losses that would result from eliminating Medicaid expansion and marketplace subsidies. It would merely free up state dollars for other purposes (such as tax cuts).

Replacing the ACA coverage provisions with a flawed block grant would not just cause large coverage losses among Medicaid and marketplace enrollees. In some states, it could cause the individual market for health insurance to collapse. In its analysis of the Cassidy-Graham bill, CBO concluded that most states “would choose to provide little support to people in the nongroup [individual] market” and certainly would not be able to replace the ACA’s subsidies, which target assistance based on income and adjust based on individual market premiums. With neither an individual mandate nor robust subsidies to draw healthier consumers into the individual market risk pool, markets in some states could unravel.[8]

In the near term, more states would likely experience very large premium increases or individual market instability. Like Cassidy-Graham, the new plan would leave 50 states and the District of Columbia on their own to redesign coverage programs from scratch, without federal guidance, standards, or administrative infrastructure. The plan would also allow states to eliminate or change many of the ACA’s consumer protections and other market rules (see below). As a result, if the new plan became law, insurers would initially have no idea how the individual market in any state would operate, and it could be years before they had clarity about the state of the risk pool.

In the interim, insurers would almost certainly impose large premium increases to account for uncertainty, and some would likely withdraw from the individual market altogether, at least temporarily. As 36 current and former insurance regulators wrote regarding Cassidy-Graham, the massive uncertainty created by that plan’s — and the new proposal’s — complete overhaul of the individual market would “severely disrupt states’ individual insurance markets, with sharp premium increases and insurer exits likely to occur in the short term and over time.”[9]

Like Cassidy-Graham, the new plan would eliminate various ACA consumer protections especially crucial for people with pre-existing health conditions. The plan authors note that “states would no longer be bound by Obamacare’s mandates such as essential health benefits [the requirement that plans cover various services], minimum loss ratio requirements [the requirement that plans spend at least a specified fraction of premium dollars on medical care and improving health quality], single risk pools [the requirement that insurers set premiums for all plans based on the assumption that enrollees are part of a single risk pool], and 3:1 age rating requirements [a limitation on the amount by which premiums for older people can exceed those for younger people].” The plan leaves ambiguous whether states could also eliminate the ACA’s prohibitions on denying coverage or charging higher premiums based on health status, specifying neither that these provisions could be dropped nor that they would remain in place. But its stated goal of lowering premiums for the young and healthy, its suggestion that states may need to take action to protect sicker individuals from higher premiums, and its clear statement that single risk pool requirements could be dropped indicate that states could likely drop these protections, as under Cassidy-Graham.[10]

Before the ACA, when decisions about pre-existing conditions protections were last left up to states, the large majority of states let insurers charge people more based on health status.[11] Consistent with that history, CBO concluded that under Cassidy-Graham, “most states” would ultimately modify market rules and “coverage for people with pre-existing conditions would be much more expensive in some of those states than under current law.” Similarly, in an unusual joint statement, America’s Health Insurance Plans, the Blue Cross Blue Shield Association, the American Medical Association, the American Academy of Family Physicians, the American Hospital Association, and the Federation of American Hospitals wrote, “the bill [Cassidy-Graham] will … undermine safeguards for those with pre-existing conditions. Without these guaranteed protections, people with significant medical conditions can be charged much higher premiums and some may not be able to buy coverage at all.”[12]

Even if the new repeal plan maintains the ACA’s ban on charging higher premiums based on health status, its consequences for people with pre-existing conditions would be similar, due to the other protections it eliminates. In particular, absent essential health benefit standards, insurers would likely drop coverage of expensive services — for example, high-cost prescription drugs — as a way to discourage enrollment by sicker, costlier enrollees. Or, if some plans did cover costly treatments, they would charge exorbitant premiums, set based on the assumption that only people needing these services would enroll.[13] Either way, people with pre-existing conditions would be left bearing the full or close to the full expected cost of their conditions — easily tens of thousands of dollars per year[14] — or, in some cases, would be unable to access the health care they need.

Because the proposed block grant could not replace the ACA coverage programs the plan would eliminate, the Cassidy-Graham bill would have resulted in large coverage losses. CBO was not given time to analyze Cassidy-Graham in full, but its preliminary analysis concluded the bill would cause millions to become uninsured. Drawing on CBO’s analyses of earlier bills, independent analysts at the Brookings Institution estimated that the September 13, 2017 version of Cassidy-Graham would have caused about 21 million people to lose coverage in the years when its block grant was in full effect.[15] That would have resulted in a non-elderly uninsured rate of about 18 percent (about 50 million people), versus 10.7 percent (29 million people) in 2017.[16] (See Figure 1.)

Since last September, Congress enacted one provision of Cassidy-Graham, repeal of the ACA’s individual mandate, as part of the 2017 tax bill. The combination of the new proposal and the already-enacted repeal of mandate would likely result in an even higher uninsured rate than would have resulted under last year’s Cassidy-Graham bill. That’s because, assuming its sponsors do not intend to increase federal deficits, it would likely provide less federal funding for coverage than Cassidy-Graham, for two reasons.

First, Cassidy-Graham funded its block grants in part with the savings from repealing the ACA’s individual mandate. But when Congress repealed the mandate as part of the tax bill, it diverted the resulting hundreds of billions in savings to help pay for tax cuts. That leaves less funding available for the block grants in the new plan.

Second, the new proposal would use some of the remaining resources from repealing ACA coverage programs to pay for a massive expansion of health savings accounts. That would further reduce the funding available for block grants and would do nothing to mitigate coverage losses from eliminating Medicaid expansion and individual market subsidies, although it would provide high-income people with additional tax sheltering opportunities.[17]

Seniors, People with Disabilities, and Families With Children Still at Risk

The new repeal plan does not include Cassidy-Graham’s provision — also included in other repeal bills last year and in the Trump Administration’s 2018 and 2019 budgets — to impose a per-enrollee cap (“per capita cap”) on federal Medicaid spending for seniors, people with disabilities, and families with children; under these proposals, the cap would grow more slowly than projected current-law Medicaid spending, resulting in growing cuts to the program over time. Already, several major conservative organizations have weighed in to urge that this provision be incorporated in any repeal proposal,[18] and the new plan does not rule out such an addition.[19]

But even without a Medicaid per capita cap, the new proposal still puts older people, people with disabilities, and families with children at risk. First, deep cuts in total federal funding for coverage would create significant financial pressure on states that could lead them to make cuts to their pre-expansion Medicaid programs, reducing benefits, eligibility, or both. Second, millions of older people, people with disabilities, and parents are covered through the ACA Medicaid expansion or receive help from the ACA’s marketplace subsidies, which the proposal would eliminate. Overall, uninsured rates for people ages 50 to 64 fell 37 percent as the ACA’s major coverage provisions took effect; uninsured rates for people with a self-reported disability fell 41 percent, and uninsured rates for parents fell 33 percent (likely helping drive coverage gains among children as well).[20] The new repeal plan, like the earlier Cassidy-Graham proposal and other repeal bills, would likely cause large coverage losses among virtually all demographic groups.[21]

Moreover, the new proposal includes a major change to the Medicaid and Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP), one not included in Cassidy-Graham, that could also pave the way for a per capita cap. Under the proposal, states would be required to let any Medicaid or CHIP enrollee “use their government assistance to buy a private health plan of their choice,” including limited-benefit plans. Presumably, states would have to let any enrollee claim premium assistance equal to the average cost of Medicaid for those in their enrollment group (e.g., seniors, people with disabilities, or parents) and use it to purchase individual market coverage.

The plan’s argument for the proposal is that Medicaid offers low-quality care at high cost. In fact, research consistently finds that Medicaid coverage improves access to care, health, and financial security and that Medicaid costs less than comparable private coverage for comparable populations.[22] Nonetheless, in the largely unregulated individual market the plan would create, healthier-than-average enrollees likely could find individual market plans with a lower cost than the average per-enrollee cost of Medicaid and with some attractive features. And since the healthiest enrollees would be the most likely to take up the option to enroll in individual market coverage, per-enrollee costs for those still enrolled in traditional Medicaid would rise, as would total program costs (counting the costs for premium assistance). That, in turn, would lead to calls to cap and cut federal Medicaid funding — as the Cassidy-Graham bill, every other repeal proposal Congress considered, and the Administration’s budget all proposed to do.