Health Coverage Rates Vary Widely Across — and Within — Racial and Ethnic Groups

End Notes

[1] The authors would like to thank Stan Dorn, Cyndi Ferguson, and Peggy Ramin for their helpful comments and suggestions.

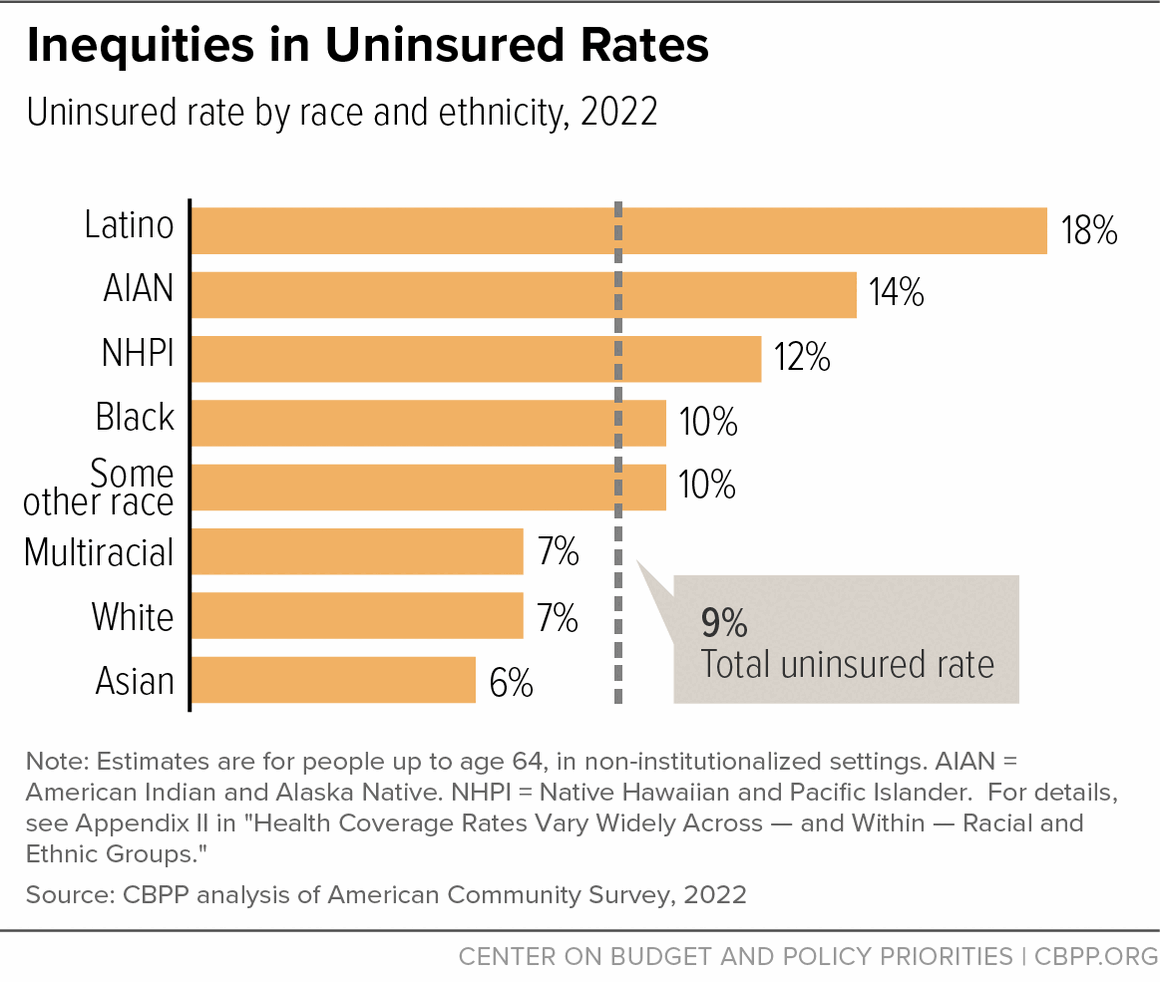

[2] CBPP analysis of 2022 American Community Survey data. Total number of uninsured among people in non-institutionalized settings.

[3] Ruqaiijah Yearby, Brietta Clark, and José F. Figueroa, “Structural Racism In Historical And Modern US Health Care Policy,” Health Affairs, Vol. 41, No. 2: Racism & Health, February 2022, https://www.healthaffairs.org/doi/10.1377/hlthaff.2021.01466

[4] This report uses the term “Latino” to refer to people of any race who identify as being of Hispanic, Latino, or Spanish origin, consistent with U.S. Census Bureau usage. This language does not necessarily reflect how everyone who is part of this community would describe themselves. For example, gender-inclusive terms like “Latinx” and “Latine” can also be used to refer to this population. These terms have emerged in recent years to represent the diversity of gender identities and expressions that are present in the community.

[5] Throughout this paper, AIAN people may be AIAN alone or in combination with other races and ethnicities. Latino people include people of any race who identify as being of Hispanic, Latino or Spanish origin. The Asian, Black, Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander, and “some other race” categories include only people who identify as a single race and not Latino, and the multiracial category does not include people who identify as Latino.

[6] Rabah Kamal et al., “How Repeal of the Individual Mandate and Expansion of Loosely Regulated Plans are Affecting 2019 Premiums,” KFF, October 26, 2018, https://www.kff.org/health-costs/issue-brief/how-repeal-of-the-individual-mandate-and-expansion-of-loosely-regulated-plans-are-affecting-2019-premiums/.

[7] Emily Gee, “Less Coverage and Higher Costs: The Trump’s Administration’s Health Care Legacy,” Center for American Progress, September 25, 2020, https://www.americanprogress.org/article/less-coverage-higher-costs-trumps-administrations-health-care-legacy/.

[8]Ibid.

[9]Gideon Lukens, “Record Low Uninsured Rate Offers Roadmap to Long-Term Coverage Gains,” CBPP, September 14, 2023, https://www.cbpp.org/blog/record-low-uninsured-rate-offers-roadmap-to-long-term-coverage-gains.

[10] Farah Kader et al., “Disaggregating Race/Ethnicity Data Categories: Criticisms, Dangers, And Opposing Viewpoints,” Health Affairs, March 25, 2022, https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/forefront.20220323.555023.

[11]Ibid.

[12] U.S. Office of Management and Budget, “Standards for Maintaining, Collecting, and Presenting Federal Data on Race and Ethnicity,” 81 Fed. Reg. 67398, September 30, 2016, https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2016/09/30/2016-23672/standards-for-maintaining-collecting-and-presenting-federal-data-on-race-and-ethnicity.

[13] Heather Saunders and Priya Chidambaram, “Medicaid Administrative Data: Challenges with Race, Ethnicity, and Other Demographic Variables,” KFF, April 28, 2022, https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/medicaid-administrative-data-challenges-with-race-ethnicity-and-other-demographic-variables/. D’Vera Cohn, Anna Brown, and Mark Hugo Lopez, “Only about half of Americans say census questions reflect their identity very well,” Pew Research Center, May 14, 2021, https://www.pewresearch.org/social-trends/2021/05/14/only-about-half-of-americans-say-census-questions-reflect-their-identity-very-well/.

[14] Linda Charmaraman et al., “How have researchers studied multiracial populations: A content and methodological review of 20 years of research,” National Library of Medicine, National Center for Biotechnology Information, July 1, 2015, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4106007/.

[15] U.S. Office of Management and Budget, “Review of the Racial and Ethnic Standards to the OMB Concerning Changes…,” July 9, 1997, https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/omb/fedreg_directive_15/.

[16] Cheryl Ulmer et al., “Race, Ethnicity, and Language Data: Standardization for Health Care Quality Improvement,” Subcommittee on Standardized Collection of Race/Ethnicity Data for Healthcare Quality Improvement Board on Health Care Services, April 2018, https://www.ahrq.gov/research/findings/final-reports/iomracereport/index.html.

[17] Robert Maxim, Gabriel R. Sanchez, and Kimberly R. Huyser, “Why the federal government needs to change how it collects data on Native Americans,” Brookings, March 30 2023, https://www.brookings.edu/articles/why-the-federal-government-needs-to-change-how-it-collects-data-on-native-americans/.

[18] U.S. Commission on Civil Rights, “Broken Promises: Continuing Federal Funding Shortfall for Native Americans,” December 2018, https://www.usccr.gov/files/pubs/2018/12-20-Broken-Promises.pdf. Diane M. Korngiebel, et al., “Addressing the Challenges of Research With Small Populations,” American Journal of Public Health, September 2015, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4539838/

[19] Malia Villegas et al., “Disaggregating American Indian & Alaska Native Data: A Review of Literature,” National Congress of American Indians, July 2016, https://nationalequityatlas.org/sites/default/files/AIAN-report.pdf.

[20] Saundra Mitrovich and Steph Glascock, “Why Collecting Disaggregated Data for Native Communities Matters,” the Leadership Conference on Civil and Human Rights, January 19, 2023, https://civilrights.org/blog/why-collecting-disaggregated-data-for-native-communities-matters/

[21] Mitrovich and Glascock, op. cit.

[22] Villegas, op. cit.

[23] United States Census Bureau, “Understanding and Using American Community Survey Data: What Users of Data for American Indians and Alaska Natives Need to Know,” April 2019, https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2019/acs/acs_aian_handbook_2019.pdf

[24]Federal Register, “Revisions to OMB’s Statistical Policy Directive No. 15: Standards for Maintaining, Collecting, and Presenting Federal Data on Race and Ethnicity,” 89 Fed. Reg. 22182, March 29, 2024, https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2024/03/29/2024-06469/revisions-to-ombs-statistical-policy-directive-no-15-standards-for-maintaining-collecting-and

[25] With the updates, the revised minimum categories are: American Indian or Alaska Native, Asian, Black or African American, Hispanic or Latino, Middle Eastern or North African, Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander, and white.

[26] Kader et al., op. cit.

[27] Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), 2024 Marketplace Open Enrollment Period Public Use Files, https://www.cms.gov/data-research/statistics-trends-reports/marketplace-products/2024-marketplace-open-enrollment-period-public-use-files.

[28]State Health Access Data Assistance Center at the University of Minnesota, “Collection of Race, Ethnicity, Language (REL) Data in Medicaid Applications: A 50-state Review of the Current Landscape,” May 25, 2021, https://www.shvs.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/SHVS-50-State-Review-EDITED.pdf.

[29]Colin Planalp, “New York State of Health Pilot Yields Increased Race and Ethnicity Question Response Rates,” State Health Access Data Assistance Center at the University of Minnesota, September 9, 2021, https://www.shvs.org/new-york-state-of-health-pilot-yields-increased-race-and-ethnicity-question-response-rates/.

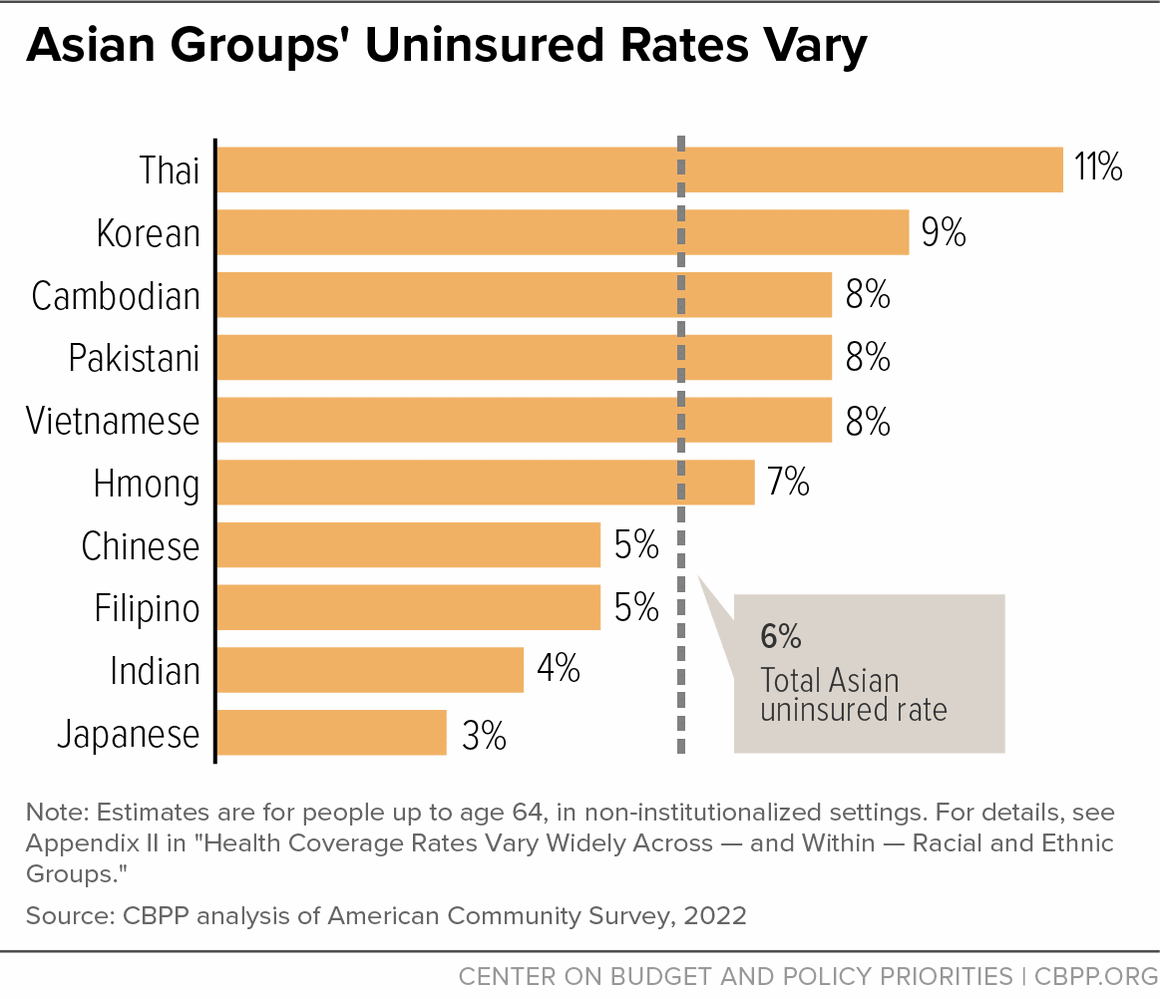

[30]CBPP analysis of 2022 American Community Survey.

[31] William R. Kerr and Martin Mandorff, “Social Networks, Ethnicity, and Entrepreneurship,” Harvard Business School, November 13, 2020, https://www.hbs.edu/ris/Publication%20Files/1%20KM%20Networks%20Full_9825ec3f-5568-40bf-8af4-962c983a4e2d.pdf.

[32]CBPP analysis of 2022 American Community Survey.

[33] CBPP analysis of 2022 American Community Survey.

[34]Mary Hanna and Jeanne Batalova, “Indian Immigrants in the United States,” Migration Policy Institute, October 16, 2021, https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/indian-immigrants-united-states-2019.

[35]Sucheng Chan, “Cambodians in the United States: Refugees, Immigrants, American Ethnic Minority,” Oxford Research Encyclopedia of American History, September 3, 2015, https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780199329175.013.317.

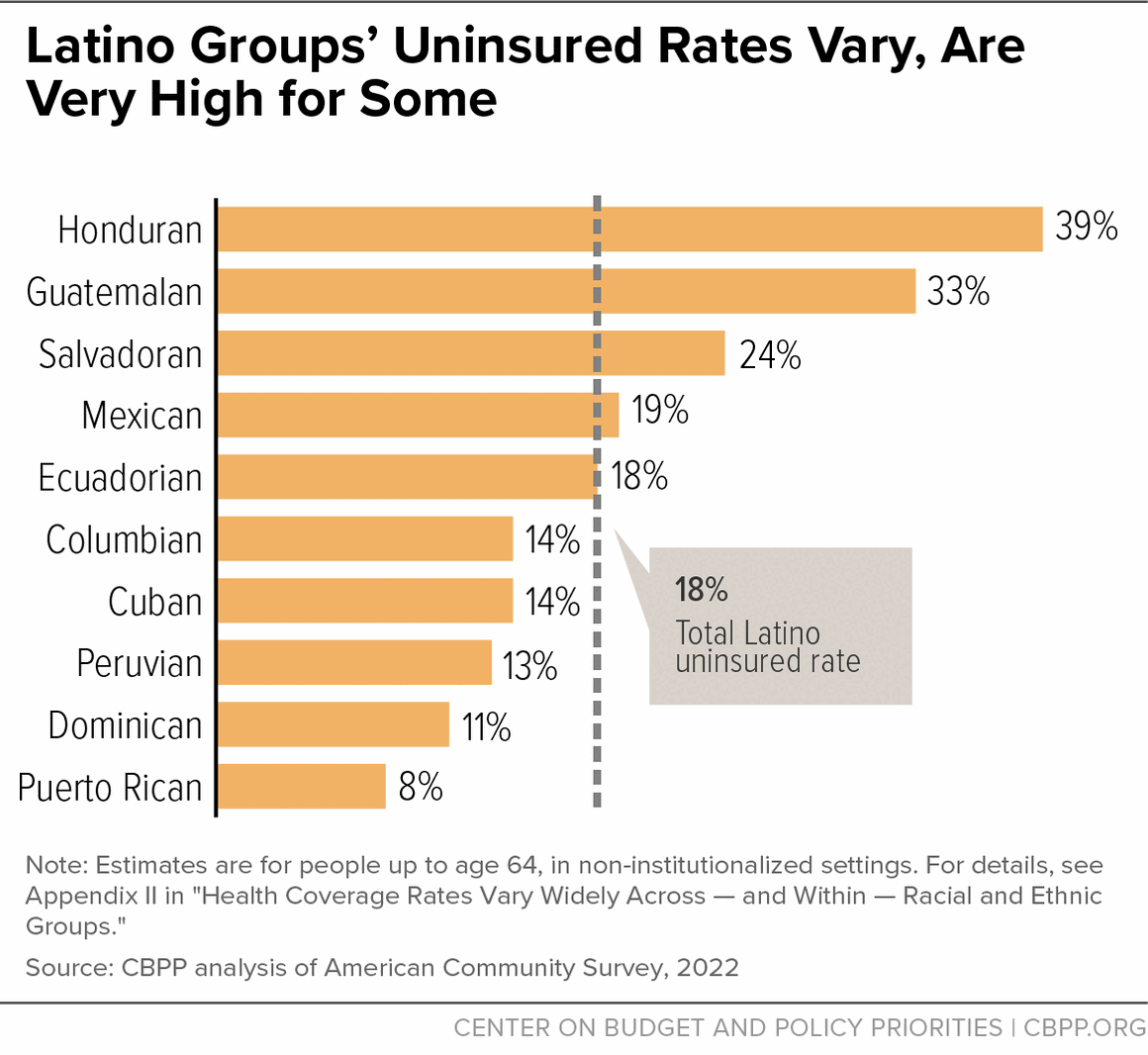

[36]CBBP analysis of 2022 American Community Survey.

[37]Erin Babich and Jeanne Batalova, “Central American Immigrants in the United States,” Migration Policy Institute, August 11, 2021, https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/central-american-immigrants-united-states.

[38]Silva Mathema and Joel Martinez, “Temporary Protected Status Is Critical To Tackling the Root Causes of Migration in the Americas,” Center for American Progress, October 28, 2021, https://www.americanprogress.org/article/temporary-protected-status-critical-tackling-root-causes-migration-americas/.

[39] Babich and Batalova, op cit.

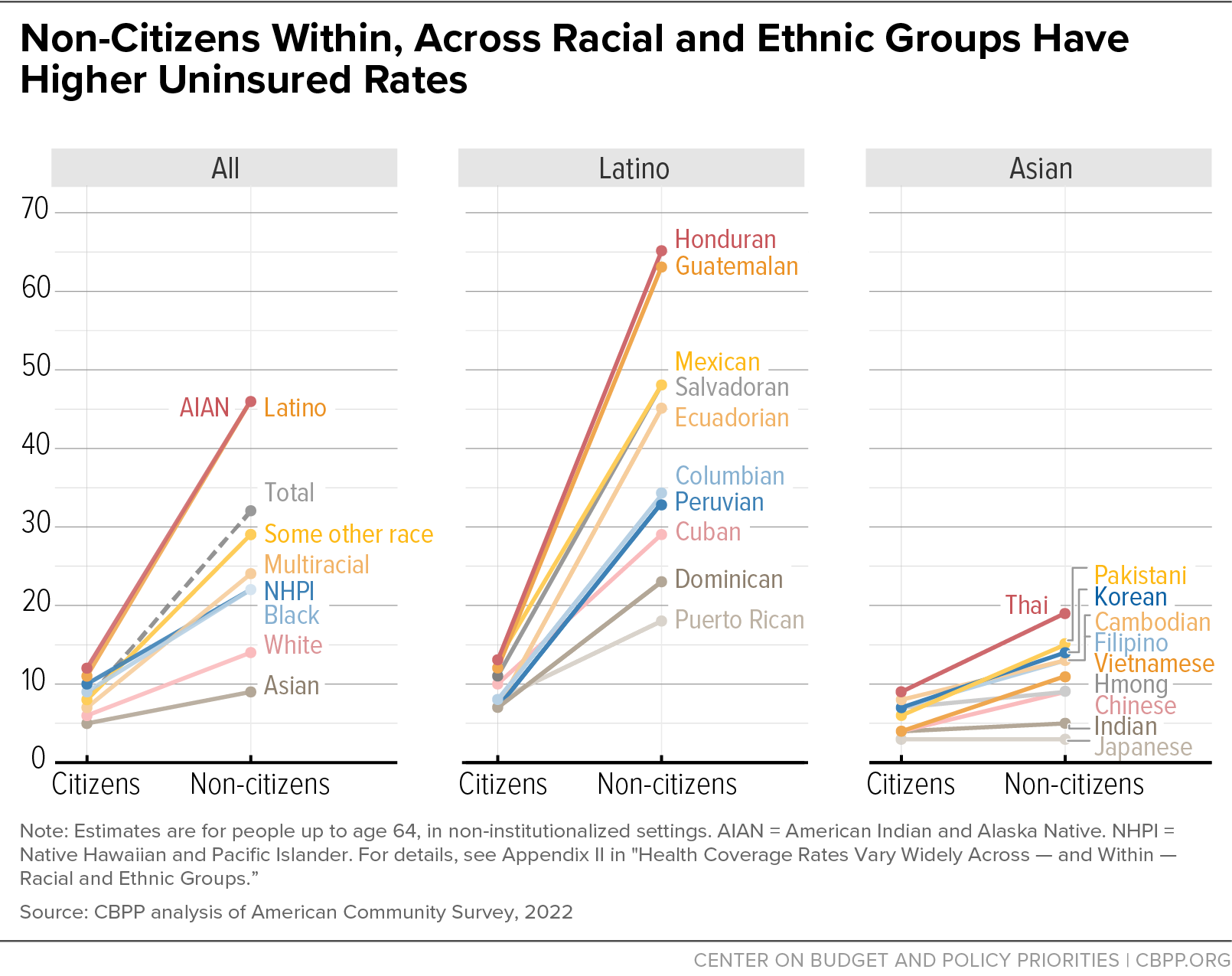

[40] “Immigrants” includes both naturalized citizens and non-citizens. United States Census Bureau, 2022 American Community Survey, “Table B05002: Place of Birth by Nativity and Citizenship Status,” https://data.census.gov/table?q=B05002&g=0100000US.

[41] Ibid.

[42] Farah Z. Ahmad and Christian E. Weller, “Reading Between the Data: The Incomplete Story of Asian Americans, Native Hawaiians, and Pacific Islanders,” Center for American Progress, February 2014, https://www.asianpacificpolicyandplanningcouncil.org/wp-content/uploads/AAPI-report.pdf.

[43]Hasna Chowdhury, “Immigration Healthcare and the Five Year Bar,” the Alliance for Citizen Engagement, August 23, 2022, https://ace-usa.org/blog/research/research-immigration/immigration-healthcare-and-the-five-year-bar/.

[44]Kyle Hayes, “Eliminating Structural Barriers Can Improve Latino People’s Access to Health Coverage,” CBPP, October 5, 2021, https://www.cbpp.org/blog/eliminating-structural-barriers-can-improve-latino-peoples-access-to-health-coverage.

[45]Akash Pillai, Drishti Pillai, and Samantha Artiga, “State Health Coverage for Immigrants and Implications for Health Coverage and Care,” May 1, 2024, https://www.kff.org/racial-equity-and-health-policy/fact-sheet/health-coverage-and-care-of-immigrants/.

[46]Valerie Lacarte, Mark Greenberg, and Randy Capps, “Medicaid Access and Participation: A Data Profile of Eligible and Ineligible Immigrant Adults,” Migration Policy Institute, October 2021, https://www.migrationpolicy.org/research/medicaid-immigrant-adults.

[47] Charles Kamasaki, “US Immigration Policy: A Classic, Unappreciated Example of Structural Racism,” Brookings Institute, March 26, 2021, https://www.brookings.edu/articles/us-immigration-policy-a-classic-unappreciated-example-of-structural-racism/.

[48] Ibid.

[49] Erica Williams, Eric Figueroa, and Wesley Tharpe, “Inclusive Approach to Immigrants Who Are Undocumented Can Help Families and States Prosper,” CBPP, December 19, 2019, https://www.cbpp.org/research/state-budget-and-tax/inclusive-approach-to-immigrants-who-are-undocumented-can-help.

[50] Pillai, Pillai, and Artiga, op. cit.

[51]Drishti Pillai et al., “Health and Health Care Experiences of Immigrants: The 2023 KFF/LA Times Survey of Immigrants,” KFF, September 17, 2023, https://www.kff.org/racial-equity-and-health-policy/issue-brief/health-and-health-care-experiences-of-immigrants-the-2023-kff-la-times-survey-of-immigrants/.

[52]Matthew Buettgens and Urmi Ramchandani, “The Health Coverage of Noncitizens in the United States, 2024,” Urban Institute, May 2023, https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/2023-05/The%20Health%20Coverage%20of%20Noncitizens%20in%20the%20United%20States%202024.pdf.

[53]Given Puerto Rico’s status as a U.S. territory, Puerto Ricans who did not immigrate to Puerto Rico are U.S. citizens.

[54] CMS, “Trends in Subsidized and Unsubsidized Enrollment,” August 12, 2019, https://www.cms.gov/CCIIO/Resources/Forms-Reports-and-Other-Resources/Downloads/Trends-Subsidized-Unsubsidized-Enrollment-BY17-18.pdf.

[55] Jennifer M. Haley et al., “One in Five Adults in Immigrant Families with Children Reported Chilling Effects on Public Benefit Receipt in 2019,” Urban Institute, June 2020, https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/102406/one-in-five-adults-in-immigrant-families-with-children-reported-chilling-effects-on-public-benefit-receipt-in-2019_1.pdf. Shelby Gonzalez, “Agencies Should Quickly End Trump Public Charge Policies, Remove Other Barriers to Public Supports,” CBPP, February 9, 2021, https://www.cbpp.org/blog/agencies-should-quickly-end-trump-public-charge-policies-remove-other-barriers-to-public.

[56] Tracy L. Renaud, Letter to USCIS Interagency Partners, U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services Office of the Director, April 12, 2021, https://www.uscis.gov/sites/default/files/document/notices/SOPDD-Letter-to-USCIS-Interagency-Partners-on-Public-Charge.pdf. HHS Press Office, “HHS Encourages States to Educate Eligible Immigrants about Medicaid Coverage,” July 22, 2021, https://public3.pagefreezer.com/browse/HHS.gov/30-12-2021T15:27/https://www.hhs.gov/about/news/2021/07/22/hhs-encourages-states-to-educate-eligible-immigrants-about-medicaid-coverage.html. Fed. Reg. 53991, “Suspension of entry of immigrants who will financially burden the United States healthcare system, in order to protect the availability of healthcare benefits for Americans,” October 9, 2019, https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2019-10-09/pdf/FR-2019-10-09.pdf.

[57]Jennifer M. Haley et al., “Many Immigrant Families with Children Continued to Avoid Public Benefits in 2020, Despite Facing Hardships,” Urban Institute, May 2021, https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/104279/many-immigrant-families-with-children-continued-avoiding-benefits-despite-hardships.pdf.

[58] Claire Heyison and Shelby Gonzales, “States Are Providing Affordable Health Coverage to People Barred From Certain Health Programs Due to Immigration Status,” CBPP, updated February 1, 2024, https://www.cbpp.org/research/immigration/states-are-providing-affordable-health-coverage-to-people-barred-from-certain.

[59] Pillai, Pillai, and Artiga, op. cit.

[60] Tricia Brooks et al., “Medicaid and CHIP Eligibility, Enrollment, and Renewal Policies as States Prepare for the Unwinding of the Pandemic-Era Continuous Enrollment Provision,” KFF, April 4, 2023, https://www.kff.org/medicaid/report/medicaid-and-chip-eligibility-enrollment-and-renewal-policies-as-states-prepare-for-the-unwinding-of-the-pandemic-era-continuous-enrollment-provision/

[61] Eric Figueroa and Iris Hinh, “More States Adopting Inclusive Policies for Immigrants,” CBPP, April 12, 2022, https://www.cbpp.org/blog/more-states-adopting-inclusive-policies-for-immigrants.

[62]Lynne Terry, “Oregon expands free health insurance for low-income residents – regardless of immigration status,” Oregon Capital Chronicle, July 6, 2023, https://oregoncapitalchronicle.com/2023/07/06/oregon-expands-free-health-insurance-for-low-income-oregonians-regardless-of-immigration-status/.

[63] Covered California, “Information for Immigrants,” https://www.coveredca.com/learning-center/information-for-immigrants/. Kristen Hwang, “California expands health insurance to all eligible undocumented adults,” Cal Matters, January 19, 2024, https://calmatters.org/health/2023/12/undocumented-health-insurance-new-california-laws-2024/. Minnesota Legislature, SF 2995, https://www.revisor.mn.gov/bills/bill.php?f=SF2995&b=senate&y=2023&ssn=0.

[64] Adults with incomes between 100 and 138 percent of the poverty level were made eligible under the ACA for both Medicaid and marketplace coverage, but they are generally not eligible for federal subsidies for marketplace coverage when Medicaid is available.

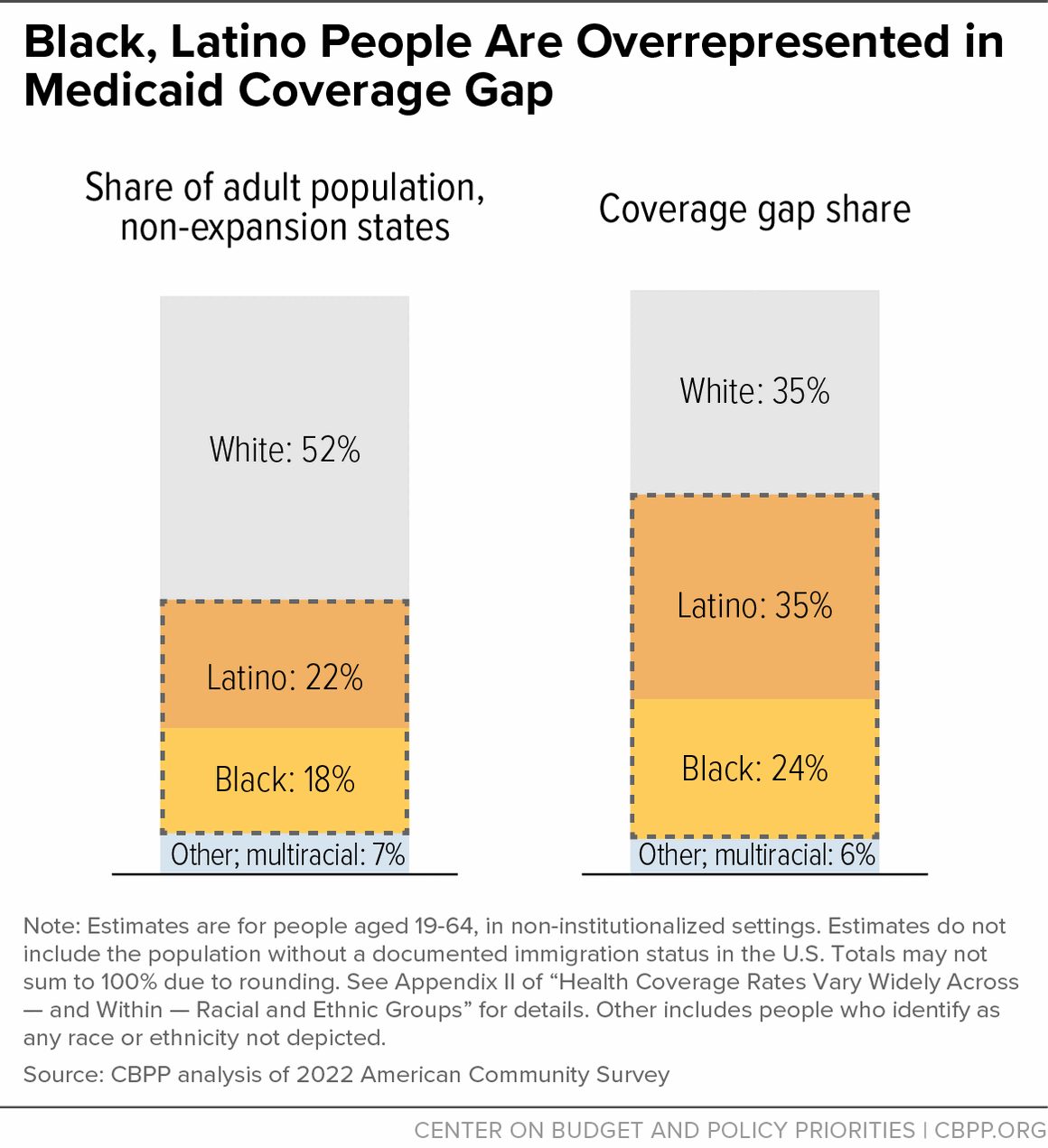

[65] CBPP, “The Medicaid Coverage Gap: State Fact Sheets,” updated April 3, 2024, https://www.cbpp.org/research/health/the-medicaid-coverage-gap.

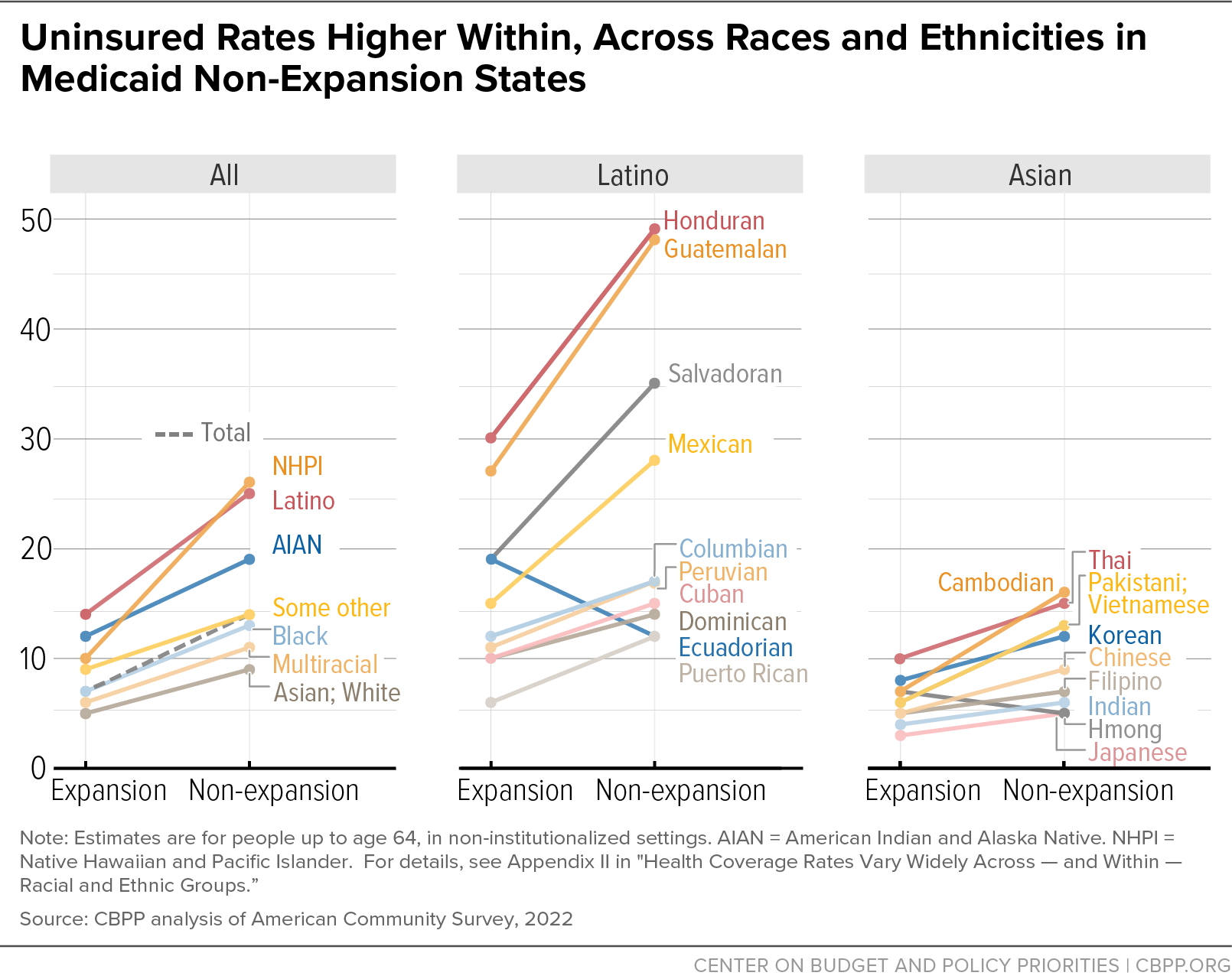

[66] CBPP analysis of American Community Survey data. Low income is defined here as income less than 200 percent of the federal poverty level. Results would be similar using data from 2019, prior to the pandemic, instead of 2022: the uninsured rate declines from 2013 to 2019 were 35 to 17 percent in expansion states and 43 to 34 percent in non-expansion states.

[67] Jesse C. Baumgartner, Sara R. Collins, and David C. Radley, “Racial and Ethnic Inequities in Health Care Coverage and Access, 2013–2019,” the Commonwealth Fund, June 9, 2021, https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/issue-briefs/2021/jun/racial-ethnic-inequities-health-care-coverage-access-2013-2019.

[68] Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Office of Health Policy, “Health Insurance Coverage and Access to Care Among Latinos: Recent Trends and Key Challenges,” October 8, 2021, https://aspe.hhs.gov/reports/health-insurance-coverage-access-care-among-latinos.

[69] Donald Warne and Linda Bane Frizzell, “American Indian Health Policy: Historical Trends and Contemporary Issues,” American Journal of Public Health, June 2014, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4035886/.

[70]Leah Frerichs et al., “Regional Differences In Coverage Among American Indians And Alaska Natives Before And After The ACA,” Health Affairs, September 2019, https://www.healthaffairs.org/doi/pdf/10.1377/hlthaff.2019.00076. Shira Rutman, Leslie Phillips, and Aren Sparck, “Health Care Access and Use by Urban American Indians and Alaska Natives: Findings from the National Health Interview Survey (2006-09),” National Institutes of Health, National Library of Medicine, 2016, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27524782/.

[71] CMS, “Medicaid & CHIP For American Indians/Alaska Natives,” CMS Product 909442-N, February 2017, https://www.cms.gov/Outreach-and-Education/American-Indian-Alaska-Native/AIAN/Downloads/Medicaid-and-CHIP-Pocket-Card.pdf.

[72] Oklahoma had the second highest population of uninsured AIAN people (behind Texas) when AIAN includes people who also identify as other races and/or Latino, and the highest population of uninsured AIAN people when AIAN includes only those identifying as a single race and not Latino. CBPP analysis of 2021 American Community Survey.

[73] Oklahoma Health Care Authority, Data and Reports, https://oklahoma.gov/ohca/research/data-and-reports.html.

[74]CBPP analysis of 2022 American Community Survey.

[75]South Dakota Department of Social Services, https://dss.sd.gov/keyresources/statistics.aspx.

[76]CBPP analysis of 2022 American Community Survey. Employment rates and uninsured rates measured among people aged 18-64 in non-institutionalized settings. Respondents are sorted into one type of coverage using the following hierarchy: Medicaid, Medicare, employer-sponsored, military (VA or Tricare), and direct purchase.

[77] Approximately 81 percent of Asian people under age 65 live in expansion states. In contrast, only 55 percent of Black people and 65 percent of Latino people live in expansion states.

[78] Jennifer Tolbert, Patrick Drake, and Anthony Damico, “Key facts about the Uninsured Population,” KFF, December 18, 2023, https://www.kff.org/uninsured/issue-brief/key-facts-about-the-uninsured-population/.

[79]CBPP analysis of 2022 American Community Survey. Respondents may report more than one type of coverage. Respondents are sorted into one type of coverage only using the following hierarchy: Medicaid, Medicare, employer-sponsored, military (VA or Tricare), and direct purchase.

[80]Raj Chetty et al. “Race and Economic Opportunity in the United States: An Intergenerational Perspective,” Harvard University, March 2018, https://scholar.harvard.edu/files/hendren/files/race_paper.pdf.

[81]McKinsey & Company, “Race in the workplace: The Black experience in the US private sector,” February 21, 2021, https://www.mckinsey.com/featured-insights/diversity-and-inclusion/race-in-the-workplace-the-black-experience-in-the-us-private-sector.

[82]CMS, “Health Insurance Marketplaces 2024 Open Enrollment Report,” March 22, 2024, https://www.cms.gov/files/document/health-insurance-exchanges-2024-open-enrollment-report-final.pdf.

[83] CMS, Marketplace Open Enrollment Period Public Use Files for 2021-2024, https://www.cms.gov/data-research/statistics-trends-and-reports/marketplace-products.

[84]In this study, AIAN is defined as people who identify as AIAN alone, not including AIAN people who also identify as other races or Latino. Also, the study combines Asian Americans and NHPI people into a single group that it labels AANHPI. Anu Warrier et al., “HealthCare.gov Enrollment by Race and Ethnicity, 2015-2023,” Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, March 22, 2024, https://aspe.hhs.gov/reports/marketplace-enrollment-race-ethnicity-2015-2023.

[85]KFF, “Distribution of Eligibility for ACA Health Coverage Among the Remaining Uninsured,” 2021, https://www.kff.org/health-reform/state-indicator/distribution-of-eligibility-for-aca-coverage-among-the-remaining-uninsured/. Jennifer M. Haley and Erik Wengle, “Many Uninsured Adults Have Not Tried to Enroll in Medicaid or Marketplace Coverage: Findings from the September 2020 Coronavirus Tracking Survey,” Urban Institute, January 2021, https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/103558/many-uninsured-adults-have-not-tried-to-enroll-in-medicaid-or-marketplace-coverage.pdf.

[86]Suzanne Wikle et al., “States Can Reduce Medicaid’s Administrative Burdens to Advance Health and Racial Equity,” CBPP, July 19, 2022, https://www.cbpp.org/research/health/states-can-reduce-medicaids-administrative-burdens-to-advance-health-and-racial.

[87]Ibid.

[88]David M. Anderson and Patrick O’Mahen, “How to Improve Consumer Plan Selection In ACA Marketplaces—Part 2,” Health Affairs, June 4, 2021, https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/forefront.20210602.122238/full/.

[89]Michel H. Boudreaux et al., “Residential High-Speed Internet Among Those Likely to Benefit From an Online Health Insurance Marketplace,” National Institutes of Health, National Library of Medicine, January 16 2018, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5798681/.

[90]Sara Atske and Andrew Perrin, “Home broadband adoption, computer ownership vary by race, ethnicity in the U.S.,” Pew Research Center, July 16, 2021, https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2021/07/16/home-broadband-adoption-computer-ownership-vary-by-race-ethnicity-in-the-u-s/.

[91]Jennifer Tolbert, Patrick Drake, and Anthony Damico, “Key Facts about the Uninsured Population,” KFF, December 18, 2023, https://www.kff.org/uninsured/issue-brief/key-facts-about-the-uninsured-population/.

[92] Patrick Drake et al., “A Closer Look at the Remaining Uninsured Population Eligible for Medicaid and CHIP,” KFF, March 15, 2024, https://www.kff.org/uninsured/issue-brief/a-closer-look-at-the-remaining-uninsured-population-eligible-for-medicaid-and-chip/.

[93]Christen Linke Young et al., “How To Boost Health Insurance Enrollment: Three Practical Steps That Merit Bipartisan Support,” Health Affairs, August 17, 2020, https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/forefront.20200814.107187/full/.

[94]Renuka Tipirneni et al., “Association Between Health Insurance Literacy and Avoidance of Health Care Services Owing to Cost,” JAMA Network Open, November 16, 2018, https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamanetworkopen/fullarticle/2714507.

[95]Lauren Woods, “Health Insurance Plans ‘Too Complicated to Understand,’” UConn Today, April 5, 2017, https://today.uconn.edu/2017/04/health-insurance-plans-complicated-understand/#.

[96] Victor G. Villagra et al., “Health Insurance Literacy: Disparities by Race, Ethnicity, and Language Preference,” American Journal of Managed Care, March 2019, https://www.ajmc.com/view/health-insurance-literacy-disparities-by-race-ethnicity-and-language-preference. U.S. Department of Education, “The Health Literacy of America’s Adults: Results From the 2003 National Assessment of Adult Literacy,” September 2006, https://nces.ed.gov/pubs2006/2006483.pdf.

[97] Nida M. Ali et al., “Addressing Health Insurance Literacy Gaps in an Urban African American Population: A Qualitative Study,” Journal of Community Health, June 20, 2018, https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10900-018-0541-x.

[98] Martha Hostetter and Sarah Klein, “Understanding and Ameliorating Medical Mistrust Among Black Americans,” the Commonwealth Fund, January 14, 2021, https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/newsletter-article/2021/jan/medical-mistrust-among-black-americans.

[99] Khiara M. Bridges, “Implicit Bias and Racial Disparities in Health Care,” American Bar Association, December 7, 2018, https://www.americanbar.org/groups/crsj/publications/human_rights_magazine_home/the-state-of-healthcare-in-the-united-states/racial-disparities-in-health-care/.

[100] Kat Stafford, Aaron Morrison, and Annie Ma, “Medical Racism in History,” AP News, May 23, 2023, https://projects.apnews.com/features/2023/from-birth-to-death/medical-racism-in-history.html.

[101] Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Office of Health Policy, “Reaching the Remaining Uninsured: An Evidence Review on Outreach and Enrollment,” October 1, 2021, https://aspe.hhs.gov/reports/reaching-remaining-uninsured-outreach-enrollment.

[102] Outreach included a combination of television, radio, direct response (text messaging, email, and autodial), internet search buys, and paid digital ads, and reflected the results of a partial open enrollment period. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, “Preliminary OE4 Lessons Learned,” https://downloads.cms.gov/files/359411146-preliminary-oe4-lessons-learned.pdf.

[103] Paul R. Shafer et al., “Television Advertising and Health Insurance Marketplace Consumer Engagement in Kentucky: A Natural Experiment,” Journal of Medical Internet Research, October 2018, https://www.jmir.org/2018/10/e10872/PDF.

[104] Joseph B. Richardson et al., “The Challenges and Strategies of Affordable Care Act Navigators and In-Person Assisters with Enrolling Uninsured, Violently Injured Young Black Men into Healthcare Insurance Coverage,” American Journal of Men’s Health, April 13, 2021, https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/15579883211005552. Karen Pollitz et al., “Consumer Assistance in Health Insurance: Evidence of Impact and Unmet Need,” KFF, August 7, 2020, https://www.kff.org/report-section/consumer-assistance-in-health-insurance-evidence-of-impact-and-unmet-need-issue-brief/.

[105] Karen Pollitz, Jennifer Tolbert, and Maria Diaz, “Data Note: Further Reductions in Navigator Funding for Federal Marketplace States,” KFF, September 2018, https://files.kff.org/attachment/Data-Note-Further-Reductions-in-Navigator-Funding-for-Federal-Marketplace-States.

[106] Tara Straw, “Marketplaces Poised for Further Gains as Open Enrollment Begins,” CBPP, October 29, 2021, https://www.cbpp.org/research/health/marketplaces-poised-for-further-gains-as-open-enrollment-begins.

[107]CBPP calculations using 2022 ACS data. Warrier et al., op. cit.

[108] Karthick Ramakrishnan and Farah Z. Ahman, “State of Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders Series,” Center for American Progress, April 23, 2014, https://www.americanprogress.org/article/state-of-asian-americans-and-pacific-islanders-series/.

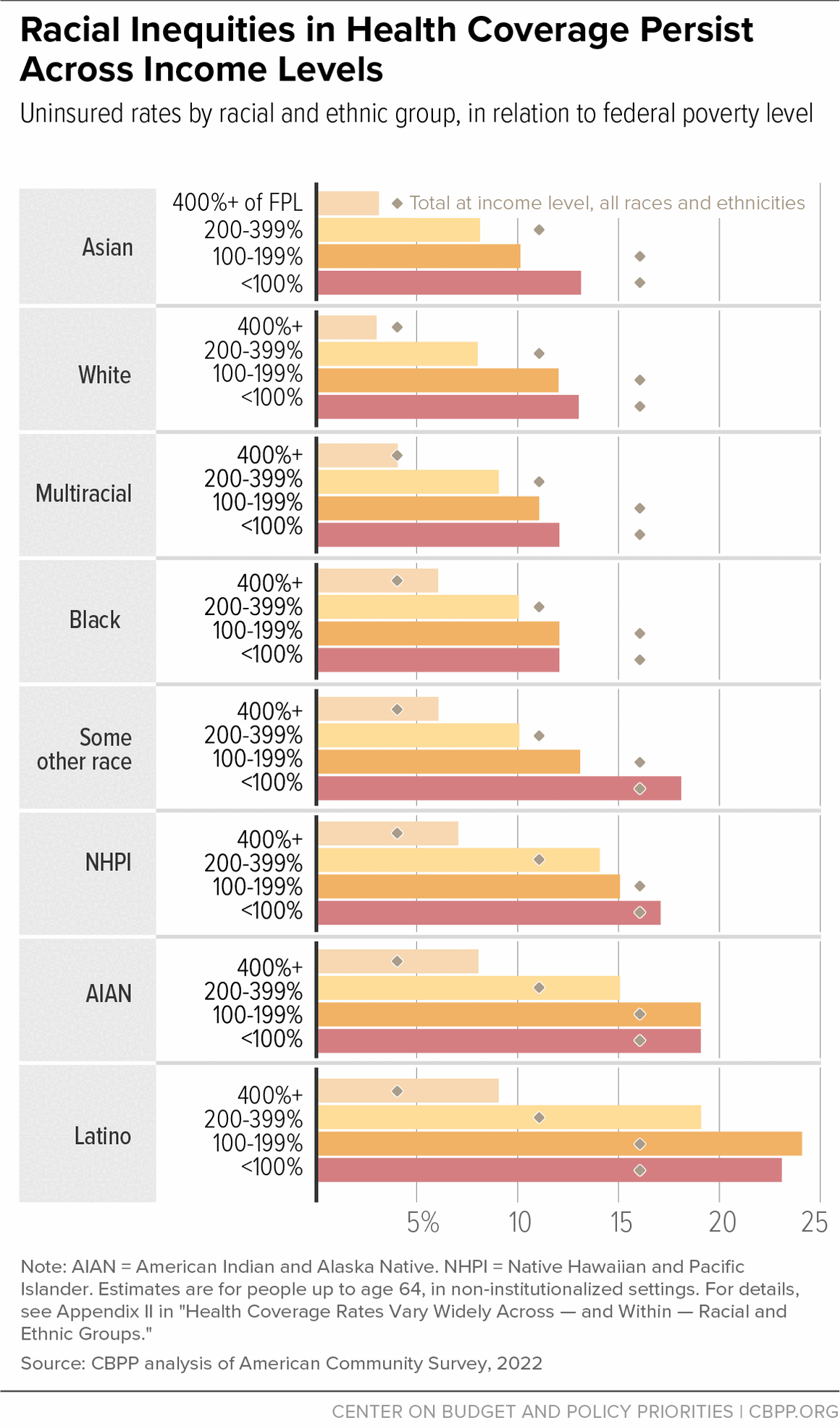

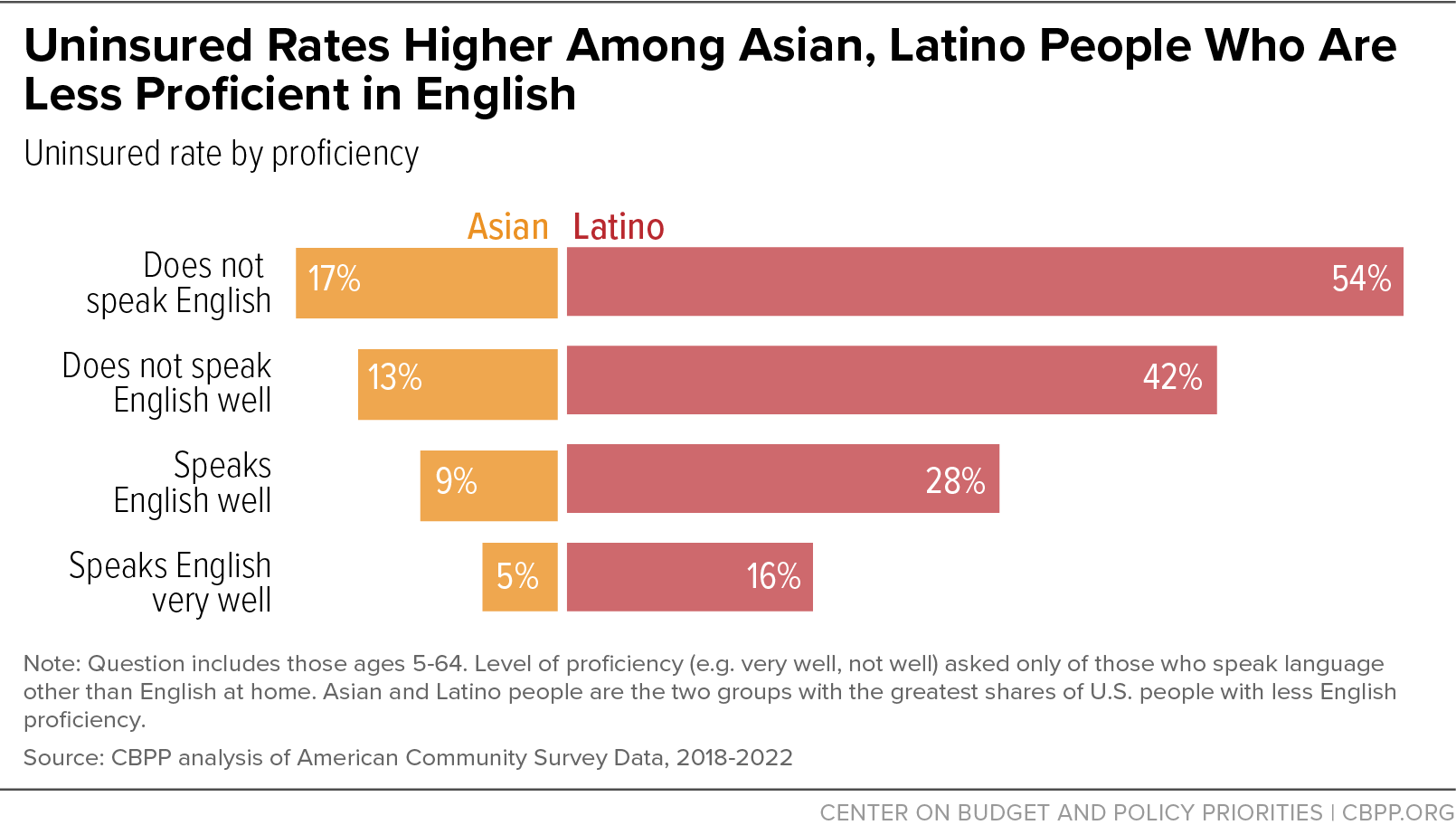

[109] Estimates for people up to age 64 in non-institutionalized settings. CBPP analysis of 2022 American Community Survey.

[110] Rubén G. Rumbaut and Douglas S. Massey, “Immigration and Language Diversity in the United States,” National Institutes of Health, National Library of Medicine, Summer 2013, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4092008/.

[111] CBPP analysis of 2022 American Community Survey.

[112] Kathy Ko Chin, “HHS Must Improve Language Access To Make Meaningful Access A Reality,” Health Affairs, July 22, 2016, https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/forefront.20160722.055907/.

[113] Colleen L. Barry et al., “Assessing the Content of Television Health Insurance Advertising during Three Open Enrollment Periods of the ACA,” Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law, December 2018, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31091327/.

[114] Lisa Aliferis, “Insurance Agents Key to California Success Enrolling Asian-Americans,” KFF Health News, March 25, 2014, https://khn.org/news/insurance-agents-key-to-california-success-enrolling-asian-americans/.

[115] Brian D. Smedley et al., “Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care,” Institute of Medicine, 2003, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25032386/. Kathleen T. Call, “Barriers to care in an ethnically diverse publicly insured population: is health care reform enough?” Medical Care, August 2014, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25023917/.