Medicaid is the largest health insurer in the United States, at over 80 million enrollees.[2] Its numerous benefits to enrollees include greater likelihood of completing school, higher wages, better health outcomes, and less medical debt compared to those who are uninsured, as well as services that let millions of seniors and people with disabilities remain in their homes and communities. Yet many people who are eligible can’t enroll or they experience gaps in coverage due to administrative burdens. And these burdens disproportionately impact people of color.

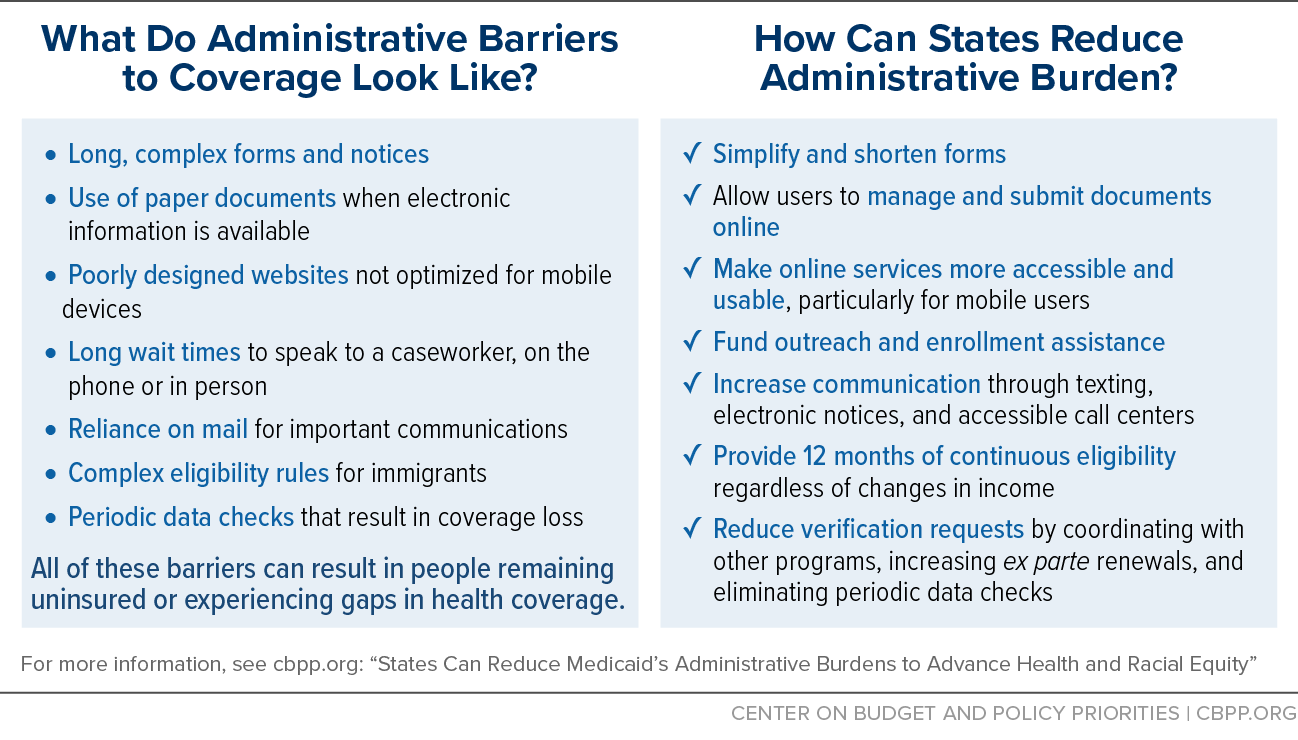

State and local governments administering Medicaid have numerous opportunities to reduce burdens on enrollees and applicants. For example, using data sources to verify eligibility, communicating via text message, and making online services more accessible can all help ease the burdens people face.

A concerted effort to streamline Medicaid is vital to increasing the ability of eligible people to participate in the program and access health care coverage and services they need, and it is critical to addressing racial health inequities. People of color face systemic racism in areas like education and employment that makes them likelier both to work in jobs with low wages and no employer coverage and to face Medicaid’s administrative burdens, such as the extra documentation required of those working multiple jobs.

“Administrative burden exacerbates inequity,” the Office of Management and Budget recently said of economic and health assistance programs. That is because burdens “do not fall equally on all entities and individuals, leading to disproportionate underutilization of critical services and programs, as well as unequal costs of access, often by the people and communities that need them the most.”[3]

People of color are disproportionately likely to rely on Medicaid for their health coverage. Nearly 60 percent of Medicaid enrollees are people of color, compared to 35 percent in employer-sponsored insurance and 25 percent in Medicare.[4] This means that access barriers in Medicaid affect a disproportionate number of people of color, sometimes leaving people without coverage and/or making the process more time consuming and difficult than is necessary.

Like with many programs, administrative burdens in Medicaid both reflect and perpetuate systemic racism and racial inequity. Many administrative burdens have their origins in explicitly racist prior law. And when people can’t access health coverage, the resulting medical debt and unmet health needs prevent many people from getting ahead. Even temporary loss of health coverage leads to a higher risk of hospitalizations for chronic conditions, lower likelihood of primary care visits, more unmet health needs, and increased medical debt.

Medicaid is a core component of our health care system, providing health insurance to about 1 in 5 people.[5] But it should be covering more people who are eligible. Seven million people are eligible for Medicaid but not enrolled.[6] Taking a critical look at Medicaid to understand how its administrative burdens disproportionately affect communities of color is vital to removing those burdens and ensuring the program better serves those who are eligible. States should take concrete steps to reduce administrative burdens, and the federal government should provide guidance, support, and accountability to create more equitable access to Medicaid and reduce health inequities.

Systemic racism includes institutional and structural racism.

- Institutional racism occurs within institutions. It involves unjust policies, practices, procedures, and outcomes that work better for white people than people of color, whether intentional or not.

- Structural racism is racial inequities across institutions, policies, social structures, history, and culture. Structural racism highlights how racism operates as a system of power with multiple interconnected, reinforcing, and self-perpetuating components which result in racial inequities across all indicators for success. Structural racism is the racial inequity that is deeply rooted and embedded in our history and culture and our economic, political, and legal systems.

Equity ensures that outcomes in the conditions of well-being are improved for marginalized groups, lifting outcomes for all. Equity is a measure of justice.

Racial equity is a process of eliminating racial disparities and improving outcomes for everyone. It is the intentional and continual practice of changing policies, practices, systems, and structures by prioritizing measurable change in the lives of people of color.

Administrative burdens include learning costs, psychological costs, and compliance costs.[7] Though people may experience all three components when navigating the Medicaid program, this report focuses on the compliance costs that government entities administering Medicaid impose on individuals through policy and operational choices.

- Learning costs are the burdens placed on individuals to research and learn about the Medicaid program, including gathering information, figuring out if they may be eligible, determining how to apply, learning what services are covered, and finding health care providers who accept Medicaid.

- Psychological costs include the stigma associated with receiving public benefits and the psychological stresses associated with navigating the bureaucratic process such as how beneficiaries are treated when applying for benefits.

- Compliance costs include the time spent filling out forms, waiting to speak with an eligibility worker, collecting the documentation required to prove eligibility, and completing the process of renewing eligibility.

Medicaid eligibility for children and parents originally depended on their eligibility for Aid to Families with Dependent Children (or AFDC, the primary cash assistance program for children of single mothers from the New Deal to 1996).[8] AFDC has a lengthy racist history and established a policy approach to public benefits as being for the “deserving” poor. Defining people as “deserving” or “undeserving” is used as a dog whistle, or veiled language, for large groups of people of color being unworthy of assistance based on unfounded negative stereotypes of laziness and abuse of government programs.

Many states implemented conduct- or morals-based AFDC eligibility rules that targeted Black and unmarried mothers. “Suitable home” requirements and policies that denied benefits if there was any sign of a “man in the house” (which could be as little as an extra toothbrush or a large pair of shoes) were applied subjectively and often unequally to Black mothers and their children. Some states halted benefits during planting and harvesting seasons to coerce Black parents to work in agricultural jobs.[9] States set their own benefit levels and income eligibility limits, and states with large Black populations — often in the South — typically set lower benefit amounts and eligibility levels.

Upon Medicaid’s enactment in 1965, these racist AFDC policies also applied to eligibility for Medicaid since the programs were linked. Tying Medicaid eligibility to that for AFDC also meant that adults without dependent children in the home were not eligible for Medicaid, a limitation that continues today in 11 states.[10]

During the 1980s and 1990s, eligibility for Medicaid was incrementally expanded to include children and pregnant women who weren’t eligible for AFDC. In 1996 the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act (PRWORA) replaced AFDC with the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) block grant and delinked Medicaid from cash assistance. Minimum Medicaid income eligibility thresholds for parents and caretaker relatives, though, were still based on states’ 1996 AFDC eligibility thresholds. States could, but were not required to, raise their income thresholds for parent and caretaker eligibility. States with large populations of Black people and other people of color — particularly those in the South — kept their thresholds at the minimum AFDC levels. Even today, states like Texas and Alabama limit eligibility for parents and caretaker relatives to those with household income below 20 percent of the federal poverty line ($4,606 annually for a family of three).[11]

After Medicaid was “delinked” from cash assistance with the 1996 PRWORA legislation, administrative burdens rooted in racist origins remained. For example, applicants subject to asset tests and interview requirements faced barriers to enrollment. Asset tests are harmful because they discourage saving among those concerned about losing benefits and impose onerous paperwork verifications on people applying for and renewing Medicaid.

PRWORA also imposed burdensome Medicaid eligibility restrictions on immigrants, most notably requiring that most lawfully present immigrants be in the U.S. for five years before qualifying for Medicaid and limiting Medicaid eligibility to certain immigrant groups.[12] For those who meet these strict eligibility criteria, the administrative burdens of proving it are significant. In 2005, the Deficit Reduction Act created a requirement for many Medicaid applicants to prove their citizenship or immigration status by submitting paper documentation (known as “cit-doc”).[13] This requirement along with the complexity of restrictions on immigrant eligibility cause additional administrative burden on eligible individuals.

More recently, a “public charge”[14] rule by the Trump Administration, since withdrawn, had a chilling effect on benefit applications from those who would have still qualified. Immigrants and people in mixed-status families, particularly Latino people, experienced — and still experience — psychological and learning costs including confusion about eligibility for Medicaid and fear about the implications of policies like public charge. And the compliance costs were high among applicants when the public charge provisions were in place. (See text box, “Administrative Burdens,” on the different types of administrative barriers.)

Notably, the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP), created in 1997, demonstrates how a streamlined process can increase program access and help eligible people enroll. Expanding coverage to children with somewhat higher incomes and state adoption of effective streamlining strategies successfully reduced paperwork and simplified the enrollment and renewal process for eligible children in many states, which helped reduce the uninsured rate among children.[15]

As enacted, the Affordable Care Act (ACA) required states to provide Medicaid to all eligible adults with incomes less than 138 percent of the federal poverty line, including those without children in the home, starting in 2014. But in 2012 the Supreme Court made expansion optional for states, and nearly a decade after the ACA’s implementation, 12 states, mostly in the South, still refuse to expand Medicaid. That has left no pathway to affordable coverage for some 2 million people, nearly 60 percent of them people of color.[16]

Section 1557 of the ACA was established to protect populations that have been marginalized, including people of color, in health care settings. The provision prohibited “discrimination on the basis of race, color, national origin, sex, age, or disability” by any entities receiving funding from the federal government, including state Medicaid programs.[17] State Medicaid agencies cannot deny, cancel, limit, or refuse to renew someone’s Medicaid coverage because of their race. They must also provide meaningful language access to the program for those with limited English proficiency. The rule also established a mechanism for enrollees to file complaints and pursue legal action if rights have been violated.

The ACA also made changes in the eligibility and enrollment process to reduce administrative burden. The law prohibits in-person interview requirements; requires that states allow people to complete their applications and renewals in person, online, through the mail, or over the phone; requires states to use available data to verify eligibility; and requires that states attempt to use electronic data to renew people’s coverage automatically, on an ex parte basis, before asking them to submit a renewal form or other documentation.

The ACA also eliminated asset tests for families with children and adults under 65 who aren’t eligible based on a disability. Asset tests are harmful to everyone because they discourage or even prevent people from saving without risking the loss of benefits. However, asset tests historically have not counted home equity. Due to historical racism that limited access to homeownership, white people with low incomes are far more likely to own their homes than people of color with the same incomes. Eliminating asset tests benefits everyone by allowing people to save as they are able, erasing the disparity of which assets are counted, and reducing the amount of paperwork verifications people need to submit to the state when applying for and renewing Medicaid.[18]

However, many states have failed to fully implement the ACA’s access requirements and continue to operate systems rife with unnecessary administrative burdens. For example, some states allow people to begin an application over the phone but require a signed form to complete the process. Many states require applicants and enrollees to submit pay stubs and other documents even though the state has access to reliable data sources that can confirm eligibility. Some states don’t even attempt an automated ex parte renewal, instead mailing a form to clients and requiring that they return it with supporting documents to continue receiving benefits.[19] By continuing to impose unnecessary administrative burdens, states and counties are impeding access to care and disproportionately affecting people of color.

Administrative burdens fall disproportionately on people of color, who are more likely to rely on Medicaid for health coverage. In 2019 Black and Latino people made up less than a third of the total U.S. population but accounted for more than half of Medicaid and CHIP enrollees.[20]

Systemic racism affecting education, employment, housing, and transportation makes people of color more likely to be unemployed or work in jobs with low wages and limited access to employer-provided coverage.[21] In 2021, 73 percent of workers paid low wages did not have access to health care through their jobs.[22] Workers who are Black or Latino have higher rates of part-time employment than white workers, and 77 percent of part-time workers did not have access to health coverage through their employers. In 2018, 55.4 percent of Black workers had private health insurance, compared to 74.8 percent of white workers.[23]

Documentation requirements especially burden Medicaid enrollees who work at low wages, part time, and/or at multiple jobs. They often must gather and submit pay stubs, provide documentation of changes in income, and prove job loss or other changes in employment. Obtaining and submitting the required documents is often difficult for part-time workers and individuals with unstable work hours who have income that varies week to week. Workers in the “gig economy” (composed disproportionately of Black and Latino workers) struggle to prove their income since they don’t receive a traditional paycheck, have income that may change substantially each month, and have to include complicated documentation of their employment expenses to show their countable income.[24]

Medicaid’s Administrative Burdens and Their Consequences

Administrative burdens prevent eligible people from enrolling and staying enrolled in Medicaid. More than 1 in 4 people under 65 are eligible for Medicaid or CHIP but are not enrolled, often due to enrollment barriers.[25] Eligible individuals may begin the application process but be unable to complete a complex application or navigate a website that doesn’t work on mobile devices. Someone may successfully enroll but then be sent a request for information a few months later that they don’t receive, don’t understand, or don’t timely respond to, resulting in loss of coverage. Finally, many eligible people lose coverage during their annual renewal because they don’t receive their notice or don’t submit the required documentation in time.

Some eligible people who can’t enroll in Medicaid remain uninsured; others become uninsured despite still being eligible.[26] Still others apply, are denied or lose coverage at some point after they enroll due to procedural reasons, then successfully reapply, in a process known as churn. Churn is costly both to individuals, who have to navigate multiple time-consuming processes, and to Medicaid agencies, which have to process additional applications. Further, many people who churn off of Medicaid experience a gap in coverage that may interrupt treatment or access to medications.

Administrative burdens causing people to remain uninsured, lose coverage, or churn on and off coverage include:

- Relying on paper documentation when electronic information is available. Requiring people to provide documents to show they are eligible is a significant barrier, particularly when information is available through electronic data sources. Most eligibility factors for Medicaid can be verified using electronic data from federal, state, and commercial entities, and Medicaid regulations strongly encourage states to use these highly reliable data sources to streamline eligibility determinations. However, many Medicaid agencies continue to require applicants or enrollees to submit paper documents such as pay stubs to prove their eligibility. This delays people’s access to health care, requires time and energy for them to gather and submit the needed documents, and often results in eligible people not enrolling in Medicaid because they were unable to submit the right documents or the agency failed to properly process them.

- Poorly designed websites. Online applications and account management portals make it easier for many people to enroll in Medicaid and update their information. However, the design of state websites, especially whether they are mobile friendly, greatly affects how easily people can use them to apply for or renew their Medicaid coverage. People with lower incomes are more likely than higher earners to rely on a smartphone for internet access.[27] When websites do not load properly on a smartphone or don’t allow people to easily enter their information, they can impede access. In contrast, websites that are designed for mobile phones, have undergone extensive user testing, and allow people to upload pictures of verification documents can increase access.[28]

- Long wait times. People attempting to enroll in Medicaid often experience long wait times, either on the phone or when waiting to speak to an eligibility worker in person. People with low incomes may have limited minutes on cell phones and can’t afford to stay on hold for long periods. People who want to meet in person with an eligibility worker may not be able to take time off work to account for long wait times or limited office hours.

- Complex immigrant eligibility rules. Immigrants must navigate a confusing web of eligibility criteria for benefit programs, including Medicaid, which impose barriers to coverage on the basis of eligibility — often due to erroneous application of the rules — but also administratively.[29] Applications may unnecessarily ask for information about people in the household who are not applying for benefits and may not have a documented immigration status.[30]

-

Periodic data checks. Once enrolled, people often face administrative barriers that can cause them to lose Medicaid before their renewal date. Thirty states check electronic data sources periodically in an enrollee’s 12-month Medicaid enrollment period to identify changes in income or other circumstances.[31] If the state finds data suggesting someone may no longer be eligible, it mails a request for information requiring the enrollee to submit documents within ten days of the date on the notice. Often, people receiving these requests may have picked up an extra shift during a pay period, switched employers, or experienced other changes that don’t affect their eligibility. But many enrollees lose coverage because they don’t receive the notice, don’t understand what action is required, or are unable to provide the required information within the tight timeframe.

Periodic data checks can lead to significant coverage loss. In Texas the number of children who experienced a gap in coverage more than doubled after implementation of a wage check policy. In Louisiana nearly 51,000 adults lost coverage after two rounds of quarterly wage checks in 2019.[32] Importantly, Louisiana acknowledged that most people lost coverage because they did not respond to the request for additional information, not because of a determination that they were no longer eligible. Frequent data checks burden Medicaid enrollees by repeatedly requiring them to prove their eligibility. Gathering income documentation is time consuming. Workers with low incomes often work inconsistent hours, may have multiple jobs from which they need to gather paperwork, and may have high turnover rates.

- Reliance on mail for important communication. Medicaid programs typically rely on postal mail for communication with applicants and enrollees and make limited use of email, text messages, or phone calls. Many low-income families with Medicaid experience housing instability and may move frequently or lack access to a reliable mailbox. Individuals who don’t receive mail from the agency requiring them to submit verification documents or renewal forms often lose coverage, even though they remain eligible, and must frequently restart the application process. Moreover, states often use mail that is returned as undeliverable as justification for terminating people’s coverage, without any attempt to reach them through other means of communication.[33]

- Complex forms and notices. Complex forms and notices are another barrier that disproportionately affects immigrants and people with limited English proficiency or low levels of literacy. Many individuals don’t complete the application process because the forms are lengthy and intimidating.

- Language access barriers. Immigrant applicants and enrollees whose first language is not English face additional barriers in accessing coverage through many stages of the enrollment and renewal process. Important notices may not be available in someone’s first or preferred language, and enrollment assistance may not be available in languages other than English. Other barriers include websites that are only available in English, inability to access forms in a preferred language, and inability to access interpreters during the application process.

In recent years, particularly during the Trump Administration, states were allowed to impose additional administrative barriers through Medicaid demonstration waivers (even though the waivers were created to allow states to test out new approaches likely to promote coverage). Increased premiums and taking away people’s benefits for not meeting work requirements were the most common barriers approved by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS). It’s well proven that both policies prevent eligible people from enrolling in Medicaid or staying enrolled. Work reporting requirements have been rightfully dismissed by the courts and the Biden Administration. But when some states were allowed to enact such policies, the data were clear that the increased paperwork requirements associated with proving employment, often on a recurring basis, led to Medicaid-eligible people losing their health insurance.a CMS recently rejected states’ efforts to continue premiums for those earning between 100 percent and 138 percent of poverty, directing the states to phase out the premiums. In its letter to Arkansas, CMS clearly stated that premiums resulted in misperceptions about the affordability of Medicaid coverage and that beneficiaries were concerned about their ability to pay premiums. In several states, premiums also led to decreased enrollment and shorter enrollment periods for Black enrollees compared to white enrollees, and for beneficiaries with lower incomes compared to those with higher incomes.b

All these barriers can result in people remaining uninsured or experiencing gaps in health coverage. Many of these barriers are likely greater for people whose primary language is not English. Even temporary loss of health coverage leads to a higher risk of hospitalizations for chronic conditions, lower likelihood of primary care visits, more unmet health needs, and increased medical debt.[34] Beyond the direct impact on people’s health when they experience a gap in health coverage, the psychological costs of churn cause confusion about eligibility rules and create frustration that leads to people’s distrust of government services.[35]

State and local governments administering Medicaid should prioritize reducing and, where possible, eliminating administrative burdens in Medicaid to advance health and racial equity. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, in its role funding and overseeing the program, should also provide guidance on best practices, policy clarity, and state accountability to make sure administrative barriers are dismantled to ensure eligible people have access to the program.

Many states have already taken action to reduce administrative burdens using the many streamlining approaches available to them. These strategies have proven to be successful in making it easier for people to enroll and stay enrolled in Medicaid. For example:

- Nine states have ex parte renewal rates of 75 percent or greater (Alabama, Arkansas, Colorado, the District of Columbia, Idaho, Michigan, North Carolina, Ohio, and Rhode Island).a

- Twenty states have mobile-friendly designs for their online Medicaid applications.b

- Michigan redesigned its public benefits application and renewal processes in partnership with Civilla, a design nonprofit. This resulted in an 80 percent reduction in application length with 90 percent of applicants completing the full application in 20 minutes or less. And 95 percent of renewals were submitted on time, with a 60 percent drop in user errors.c

- In partnership with Code for America, the state of Louisiana launched LA’MESSAGE, a pilot one-way text messaging service that broadcasts reminders and guidance to clients at key points throughout the benefits enrollment and renewal process.d

- New Mexico eliminated unnecessary application language requesting Social Security numbers for non-applicants.e

- In Pennsylvania, the ability to upload verification documents via mobile application has resulted in 5.4 million verifications submitted through the app across benefit programs including Medicaid since its launch in 2017.f

- Seven states — Arkansas, California, Illinois, Montana, New Jersey, Oregon, and West Virginia — used SNAP participation data to enroll more than 725,000 people in Medicaid from 2014 to April 2016.g

a Tricia Brooks et al.

b Ibid.

c Civilla, “Project Re:Form,” https://civilla.org/work/project-reform; Civilla, “Project Re:New,” https://civilla.org/work/project-renew.

d Code for America, “LA’MESSAGE,” https://www.codeforamerica.org/features/louisiana-demo/.

e Sovereign Hager, “Practical Changes State Agencies Can Make to Increase Equity in Application Processes for Immigrant Families,” New Mexico Center on Law and Poverty, December 2020, https://www.clasp.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/2020_NM-ASAP.pdf.

f Pennsylvania Department of Human Services, COMPASS Updates, presentation at Quarterly Community Partners Workgroup Meeting, April 13, 2022.

g Shelby Gonzales, “States Can Use Existing Information to Reduce Number of Uninsured,” CBPP, April 14, 2016, https://www.cbpp.org/blog/states-can-use-existing-information-to-reduce-number-of-uninsured.

Examples of actions include:

- Implementing 12-month continuous eligibility. States should provide 12 months of eligibility for enrollees regardless of changes in income, which would reduce churn, eliminate the burden of requests for information based on periodic data checks, and improve people’s access to health care and financial well-being.[36] Twenty-eight states have adopted 12-month continuous eligibility for children through a state option.[37] States can also implement 12-month continuous eligibility for adults through a demonstration waiver under section 1115 of the Social Security Act. New York and Montana are the only states that have adopted continuous eligibility for all adults, although Montana is poised to end 12-month continuous eligibility in the coming months. Kansas provides 12-month continuous eligibility for adults eligible through Section 1332 guidelines.[38]

- Making online services more accessible. Online services can significantly reduce administrative burden by allowing individuals to apply for or manage their benefits anytime from anywhere. State Medicaid applications and case management portals should be easily navigable when accessed on a mobile device; not require burdensome identity proofing or login procedures, beyond what is necessary for security purposes; be available in multiple languages; and allow users to upload pictures of documents taken with their phones.

- Reducing verification requests. Federal Medicaid policy allows — and in many cases requires — states to rely on electronic data sources to verify Medicaid eligibility for applicants and enrollees. By expanding the number of data sources and increasing reliance on data that are already available, states can minimize requests for documents, expedite eligibility determinations, and greatly reduce the burden on Medicaid applicants and enrollees. States should try to obtain information through electronic databases before asking an applicant or enrollee to provide documents and eliminate unnecessary requests for documents. To do so they should:

- Coordinate with other programs. Many people enrolled in or applying for Medicaid are also enrolled in other public benefit programs, such as the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP). Agencies should use information from these programs to expedite enrollment and renewals and minimize the number of documents individuals must submit. States should identify areas for greater collaboration and data sharing, such as using SNAP income information to automatically renew Medicaid eligibility when the SNAP data indicate ongoing Medicaid eligibility.[39]

- Increase ex parte renewals. Medicaid agencies must attempt to renew eligibility for Medicaid enrollees by reviewing available data sources to confirm their ongoing eligibility — through ex parte renewal — before requiring an enrollee to submit any documents to the agency. Most Medicaid agencies could substantially increase the number of cases they renew through the ex parte process, which would eliminate the need to require enrollees to submit a renewal form and supporting verifications.[40] The federal government should monitor and enforce the requirement for ex parte renewals and help states implement them to the fullest extent possible. States should use current income information from other benefit programs (for example SNAP) as income verification for Medicaid ex parte renewals, and regularly provide data on their ex parte rates and the reasons renewals fail the ex parte process.

- Eliminate or modify periodic data matches. Periodic data checks frequently flag households who have experienced minor changes in income and put them at risk of losing Medicaid coverage if they don’t quickly respond with proper verification documents. There is no federal requirement for states to conduct periodic data checks and this “gotcha” policy harms low-paid workers with multiple jobs or those who switch jobs throughout the year. Eliminating periodic data checks is the most equitable policy solution. Failing that, Medicaid agencies should modify the criteria for periodic data matches to only identify households who have experienced substantial changes in income or other factors that may affect eligibility.

- Improving communications with enrollees and applicants. Administrators should reassess how their state and county offices communicate with Medicaid applicants and enrollees, including improving notices and ensuring that applicants and enrollees receive them in a timely manner and in their preferred language. Agencies should expand beyond their traditional reliance on mailed notices and increase communication through text messaging, electronic notices, and accessible call centers. States should engage Medicaid enrollees to gather feedback on communications and recommendations for improvements.

- Funding outreach and enrollment assistance. About a quarter of uninsured people are eligible for Medicaid, but perceptions of ineligibility, confusion about how to apply, and complex application processes deter them from enrolling.[41] These barriers are particularly acute for recent immigrants and people whose first language is not English. Evidence from the ACA’s coverage expansions shows that public outreach campaigns, free and unbiased in-person assistance, and outreach from trusted community partners like hospitals and community-based organizations can help eligible people navigate these challenges.[42] Distribution of funding for outreach and enrollment assistance must ensure everyone has access to these services, including communities with large numbers of immigrants and other communities with specific barriers to coverage. States should invest in outreach campaigns and fully fund agency personnel in order to ensure there are sufficient caseworkers to handle call volume and provide timely application assistance.