President-elect Trump, House Speaker Paul Ryan, and Health and Human Services Secretary nominee Tom Price support radically changing Medicaid’s basic structure by converting the program to a block grant or what is known as a “per capita cap” and reducing federal funding for the program over time. They and other supporters of a block grant or per capita cap contend that under this approach, states would receive new flexibility to innovate and lower their costs.

But this is a very dubious promise. Every House Republican budget plan of the past five years, and the most recent joint House-Senate budget plan (in 2015), would have implemented these structural changes in a way that would cut federal Medicaid funding by approximately $1 trillion over ten years and even more in the decades after that, in addition to repealing the Affordable Care Act’s Medicaid expansion, which would withdraw roughly another $1 trillion in federal Medicaid funding for states over ten years.

As a result, states would need to use the increased flexibility they would get in conjunction with a block grant or per capita cap primarily to cut benefits, eligibility, and provider payments and eliminate beneficiary protections. Moreover, federal funding cuts of this nature likely would stymie various innovative efforts that states have underway to improve health care delivery and generate long-term savings — and would impede future such efforts — because such reforms often require upfront investment that would be harder for states to make due to the substantial federal funding reductions.

Medicaid is a federal-state partnership. The federal government pays a significant share of the program’s costs, and states agree to follow federal rules that set minimum standards for eligibility, benefits, beneficiary protections, provider payments, and how benefits are delivered. There are some things that states must do, such as making almost all poor children eligible.[1] But the rules also give states a great deal of flexibility. As one example, benefits such as dental and vision care, physical therapy, and even prescription drugs are entirely optional for adults; states decide whether to cover them or not and to what degree.

States also have leeway on how they deliver health care. They can make monthly payments to managed care organizations that are responsible for delivering Medicaid-covered services to their members, or they can set up accountable care organizations, which are groups of providers that agree to coordinate care for groups of beneficiaries in exchange for monthly payments. New options created under health reform such as health homes have allowed states to provide intensive care coordination to beneficiaries who have made unnecessary and frequent visits to the emergency room. Missouri’s health homes program is credited with producing better health outcomes while reducing state costs. [2]

Every state designs its Medicaid program to fit its needs and environment. For example, some states have large public hospital systems; others have largely private systems of care. Some states rely heavily on managed care organizations to deliver care, while others use provider-sponsored organizations or pay providers on a fee-for-service basis.

Medicaid also is the primary payer for long-term services and supports, including nursing facility care and home health, the need for which is expected to grow as the population ages.[3] Using Medicaid’s flexibility — including a number of new state options that the Affordable Care Act (ACA) created — states have shifted much of their spending on long-term services and supports from nursing homes and other institutions to home- and community-based services (HCBS) so more people can stay in their homes and communities. In 1995, HCBS accounted for just 18 percent of spending on long-term services and supports, but by 2014 its share had increased to 53 percent.[4]

Medicaid also provides the foundation for various innovative and effective health-related programs for children. Some states use Medicaid to help fund home visitation services by nurses or to provide enhanced primary care services, both of which are aimed at fostering children’s healthy development. Various states also use Medicaid funding to screen for maternal depression and connect mothers and children to necessary treatment.[5]

In addition, Medicaid gives states flexibility to respond to an array of public health and other problems and emergencies. For example, states like West Virginia, Maryland, New Hampshire, Illinois, and Massachusetts are working to address the opioid epidemic by creating evidence-based systems of care for people with substance use disorders. States like Louisiana and Texas have provided mosquito repellent to Medicaid beneficiaries to prevent transmission of the Zika virus. Michigan is using Medicaid to help address the lead crisis in Flint.

Demonstration projects authorized under section 1115 of the Social Security Act — usually referred to as Medicaid waivers — provide states with even greater flexibility to try new ways of delivering care. Over the last several years, states like Oregon, Texas, Massachusetts, and New York have used upfront federal Medicaid funds made available through Medicaid waivers to pay the costs of building an infrastructure to provide improved coordination and communication across providers — which is essential for improving delivery systems and saving money in the long term. Oregon’s emergency department visits and preventable hospital admissions have fallen significantly, and the state has lowered its Medicaid spending growth by two percentage points below the levels projected in the absence of the waiver. [6]

The federal government pays a fixed percentage of each state’s Medicaid costs in providing covered services to all eligible beneficiaries who apply. Block grants and per capita caps are fundamentally different. They provide fixed amounts of federal funds to states that, under every Medicaid and per capita cap proposal of recent years, are set below the amounts states are projected to need to provide health care to beneficiaries (and would receive under current law). Block grants and per capita caps save money for the federal government by shifting costs to the states, with the magnitude of the cost shift growing larger each year. States are then left to make the hard decisions on how to deal with the increasingly inadequate federal funding.[7]

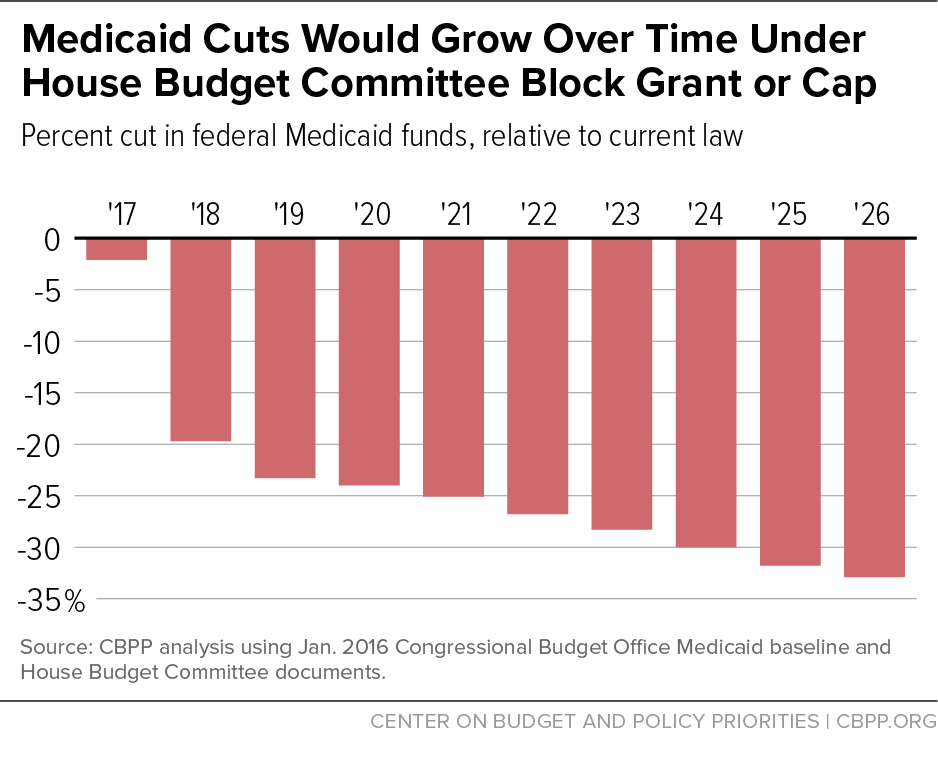

For example, the budget plan for fiscal year 2017 that the Republican majority on the House Budget Committee adopted last spring would have given states the choice of a block grant or per capita cap and thereby reduced federal Medicaid spending by $1 trillion over ten years — a 25 percent cut — on top of repealing the ACA’s Medicaid expansion. The federal Medicaid funding cuts over the decade would grow to a reduction of 33 percent by the tenth year and grow still larger in subsequent years. (See Figure 1.)

When House Republican leaders unveiled a similar approach as part of their “Better Way” policy agenda in June 2016, they said that states could compensate for the losses in federal funding by using new flexibility to cut costs without harming beneficiaries. But that is highly unlikely. Medicaid costs per beneficiary already are far below those of private insurance, after adjusting for differences in health status, and have been growing more slowly than private insurance costs in recent years (and are expected to continue doing so).[8]

Moreover, the reality is that significant innovation is occurring in most states today because of Medicaid’s flexibility and its financing structure. Federal funding cuts of the magnitude that Republican leaders have proposed would endanger this innovation. States would have to quickly figure out how to live within fixed, inadequate amounts of federal funds, making it much harder for them to continue making the upfront investments that generally are needed to develop systems that can provide high quality care at lower costs.

If Congress caps federal Medicaid funding through a block grant or per capita cap, state policymakers will have to deal with the funding shortfalls the caps create. In the short term, they might try to avoid cutting eligibility or benefits and attempt instead to fill the funding shortfall by imposing premiums, higher cost-sharing, cuts in provider payments, or changes that make it harder for prospective beneficiaries to enroll.

Just as it’s easier for federal policymakers to use arbitrary caps to cut federal Medicaid funds and leave the hard decisions to states, so would these types of changes generally make squeezing Medicaid easier for state policymakers because the impact of these changes often isn’t transparent. The number and characteristics of people who lose coverage due to explicit eligibility restrictions are identifiable. But the impacts on enrollment and access to care of making it more difficult for people to enroll, or of making beneficiaries bear greater out-of-pocket costs when they use care, wouldn’t be known clearly when the change was considered and adopted. This is of particular concern, given that many of those harmed by enrollment barriers or increases in out-of-pocket costs are likely to be the poorest, most vulnerable beneficiaries.

- Onerous requirements make it harder to enroll or remain enrolled. The ACA accelerated and supported work already underway to simplify the process of enrolling in health coverage, by increasing the use of online applications and electronic data sources, allowing states to use information collected in determining eligibility for SNAP (formerly known as food stamps), and streamlining the process for annually renewing coverage. To limit enrollment as a way of coping with reduced federal funding, states could return to requiring paper documentation, face-to-face interviews, and other such requirements, which decrease participation. For example, under legislation enacted in 2006, states were required for several years to ask families to present proof of their citizenship and identity — generally by producing a birth certificate or passport — when they applied or renewed their Medicaid coverage. In the eight months after this requirement took effect, states reported large declines in Medicaid enrollment, particularly among low-income children.[9] (This requirement was subsequently modified to allow states to use Social Security Administration databases to confirm citizenship or eligible legal immigrant status in most cases.)

-

Premiums, too, decrease participation. The Medicaid statute bars states from requiring people with incomes below 150 percent of the poverty line to pay premiums for their Medicaid coverage, though the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services has allowed several states to charge premiums under Medicaid waivers, principally for people with incomes over 100 percent of the poverty line. States have not, however, been allowed to terminate coverage for beneficiaries with incomes under the poverty line for not paying premiums. These federal rules would likely be abandoned under a block grant or per capita cap. A robust body of research shows that imposing premiums on low-income people leads significantly fewer to enroll.[10]

Furthermore, charging premiums is likely to decrease participation among the poorest participants who are least able to pay monthly premiums. For example, in 2003, Oregon received approval to amend its existing Medicaid waiver to increase premiums charged to people with very low incomes. Research found that following these changes, enrollment in Oregon’s waiver program dropped by almost half.[11]

-

Co-payments reduce low-income people’s use of necessary care. Like premiums, charging co-payments for doctor’s visits, prescriptions, and other services would lower state costs for health care without cutting covered benefits. Yet research shows co-payments can create barriers to care for low-income people, with the greatest impact on those who can least afford to pay.

For example, in Washington, 20 percent of those enrolled in the state-funded Basic Health program — a program that covered low-income adults with incomes up to 200 percent of the poverty line who were not eligible for Medicaid — went without needed care over a five- to six-month period as a result of the increased cost-sharing requirements the state adopted.[12] Similarly, Medicaid beneficiaries enrolled in the Healthy Indiana Plan 2.0 who had to pay significant cost-sharing charges were less likely to use preventive, primary, and specialty care than beneficiaries who weren’t subject to co-pays. They were also more likely to use the emergency room, including for non-emergency reasons, and less likely to adhere to their prescription drug regimens for chronic conditions such as asthma, arthritis, and heart disease.[13]

-

Cutting provider payments makes it harder to get care. Federal requirements that provider payments be adequate to ensure that beneficiaries can obtain health services they need also would likely be withdrawn as part of new state flexibility. In states that pay providers on a fee-for-service basis, the federal standards require that states monitor access to care to determine the sufficiency of provider payments. And in states with managed care, the plans are required to establish provider networks that meet certain time and distance standards. States must pay the plans “actuarially sound” rates that are adequate to ensure beneficiaries can obtain necessary covered services.

Eliminating or eroding these standards likely would mean that substantial numbers of beneficiaries would have a harder time finding providers or would have to travel long distances. Again, beneficiaries with the fewest resources (such as poor beneficiaries without cars who live in rural areas) would be those most likely to miss out on necessary care.

As state funding shortfalls resulting from the reductions in federal funding grew larger over time, most states would eventually have to make explicit cuts in eligibility and benefits and/or make further cuts in provider payments. In an examination of an earlier Medicaid block grant proposal from House Speaker Paul Ryan that is similar to the proposal in last year’s House Republican budget plan, the Urban Institute estimated it would lead to between 14 and 21 million people losing their coverage, on top of those who would lose coverage due to repeal of the Medicaid expansion.[14]

Cuts of that magnitude would almost certainly affect some groups of beneficiaries whom states currently are required to cover, such as children and pregnant women with incomes below 138 percent of the poverty line. States likely would also be allowed to institute waiting lists or to cap enrollment to limit the number of people with coverage. Poor seniors and people with disabilities would be at risk, as well, since health care costs for those people comprise almost half of all Medicaid spending.

Another example concerns the roughly 30 million low-income children enrolled in Medicaid’s Early, Periodic, Screening, Diagnosis, and Treatment (EPSDT) services. Under the federal EPSDT requirement, states must provide regular health screenings for children on Medicaid and determine through the screenings whether the children are hitting — or falling behind — key developmental benchmarks. States are required to provide needed treatment if the screenings find that children have health problems, even if the treatment in question — such as dental care, eyeglasses, or special equipment such as a wheelchair — isn’t covered for the state’s adult Medicaid beneficiaries. The increased state flexibility that would accompany a block grant or per capita cap would likely include removal of the EPSDT requirement, which would place vulnerable children at risk of having various conditions going undiagnosed and not being treated on a timely basis, if at all.

Converting Medicaid to a block grant or a per capita cap — as Republican leaders support — would lead over time to a drastic cut in federal funding for the program. Although supporters of a block grant or per capita cap contend that such a structure would give states new flexibility to innovate and lower their costs, it’s likely that states would need to cut benefits, eligibility, and provider payments and eliminate beneficiary protections to close the resulting funding gaps. Innovations already underway — and those possible in the future — to improve health care delivery and generate long-term savings would be stymied.