Recovery Legislation Could Help End Summer Childhood Hunger

End Notes

[1] Food Research & Action Center, “Hunger Doesn’t Take a Vacation: Summer Nutrition Status Report,” August 2020, https://frac.org/wp-content/uploads/FRAC-Summer-Nutrition-Report-2020.pdf.

[2] For more information about this option, known as the Seamless Summer Option, see Food and Nutrition Service, “An Opportunity for Schools,” U.S. Department of Agriculture, August 13, 2013, https://www.fns.usda.gov/cn/opportunity-schools.

[3] Food Research & Action Center, op. cit.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Mark Nord and Kathleen Romig, “Hunger in the Summer: Seasonal food insecurity and the National School Lunch and Summer Food Service programs,” Journal of Children and Poverty, Vol. 12, No. 2, 2006, pp. 141-158, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/10796120600879582; Jin Huang, Ellen Barnidge, and Youngmi Kim, “Children Receiving Free or Reduced-Price School Lunch Have Higher Food Insufficiency Rates in Summer,” Journal of Nutrition, Vol. 145, No. 9, September 2015, pp. 2161-68, https://doi.org/10.3945/jn.115.214486.

[6] Daniel P. Miller, “Accessibility of summer meals and the food insecurity of low-income households with children,” Public Health Nutrition, Vol. 19, No.11, August 2016, pp. 2079-89, https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/public-health-nutrition/article/accessibility-of-summer-meals-and-the-food-insecurity-of-lowincome-households-with-children/0D371AD6B660E965FBAFA6BFF328F824.

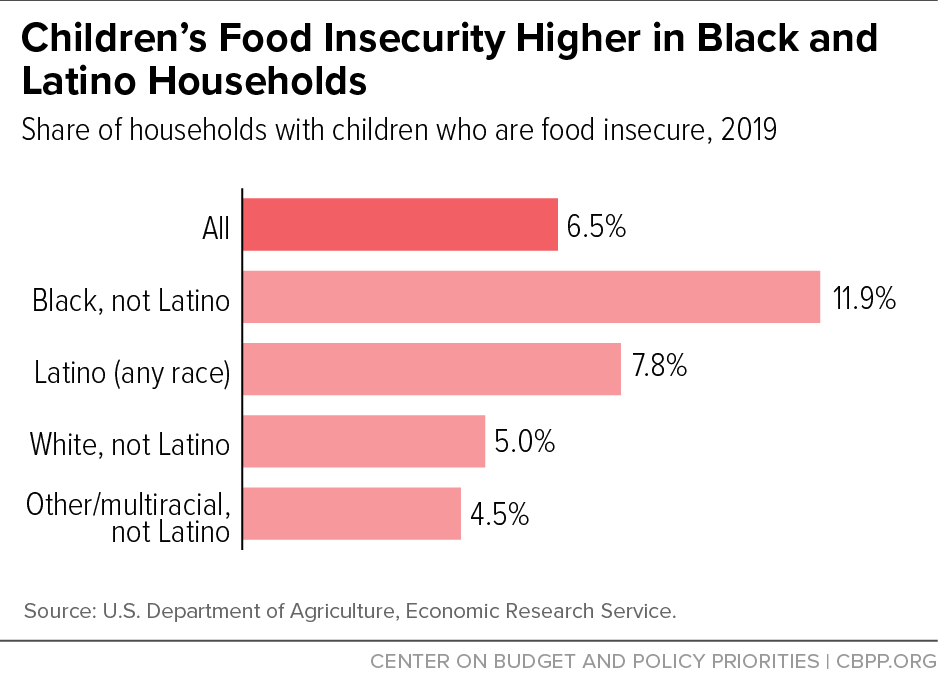

[7] Household race is based on the race of the person in whose name the housing unit is owned or rented. Alisha Coleman-Jensen et al., “Household Food Security in the United States in 2019,” Economic Research Service, Department of Agriculture, September 2020, Table 3, https://www.ers.usda.gov/webdocs/publications/99282/err-275.pdf.

[8] Coleman-Jensen et al., op. cit.

[9] David M. Quinn and Morgan Polikoff, “Summer learning loss: What is it, and what can we do about it?” Brookings Institution, September 14, 2017, https://www.brookings.edu/research/summer-learning-loss-what-is-it-and-what-can-we-do-about-it/.

[10] Claire Zippel and Arloc Sherman, “Bolstering Family Income Is Essential to Helping Children Emerge Successfully From the Current Crisis,” CBPP, updated February 25, 2021, https://www.cbpp.org/research/poverty-and-inequality/bolstering-family-income-is-essential-to-helping-children-emerge.

[11] Edward Frongillo, Diana F. Jyoti, and Sonya J. Jones, “Food Stamp Program Participation Is Associated with Better Academic Learning among School Children,” Journal of Nutrition, Vol. 136, No. 4, 2006, pp. 1077-80, http://jn.nutrition.org/content/136/4/1077.full; and Hilary Hoynes, Diane Whitmore Schanzenbach, and Douglas Almond, “Long-Run Impacts of Childhood Access to the Safety Net,” American Economic Review, Vol. 106, No. 4, 2016, pp. 903-934. P-EBT distributes benefits through the same EBT cards and financial management system that states and the Agriculture Department use for SNAP benefits.

[12] P.L. 117-80 § 748.

[13] Prior to 2006, households with low food security were described as “food insecure without hunger,” and households with very low food security were described as “food insecure with hunger.” Although changes in these descriptions were made in 2006 at the recommendation of the Committee on National Statistics (to distinguish the physiological state of hunger from indicators of food availability), the criteria by which households were classified remained unchanged. Coleman-Jensen et al., op. cit.

[14] Ann M. Collins et al., “Summer Electronic Benefit Transfer for Children (SEBTC) Demonstration: Summary Report,” Abt Associates and Mathematica Policy Research, May 2016, https://fns-prod.azureedge.net/sites/default/files/ops/sebtcfinalreport.pdf.

[15] Ibid.

[16] CBPP, “CBPP/FRAC P-EBT Documentation Project Shows How States Implemented a New Program to Provide Food Benefits to Up to 30 Million Low-Income School Children,” www.cbpp.org/pebt.

[17] All 50 states, the District of Columbia, and the Virgin Islands implemented P-EBT for the spring of the 2019-2020 school year. USDA has approved P-EBT plans for 49 states, the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico, the Virgin Islands, and the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands for the 2020-2021 school year; the state awaiting approval is Wyoming. See USDA, “State Guidance on Coronavirus P-EBT,” June 28, 2021, https://www.fns.usda.gov/snap/state-guidance-coronavirus-pandemic-ebt-pebt.

[18] Lauren Bauer et al., “The Effect of Pandemic EBT on Measures of Food Hardship,” Hamilton Project, July 2020, p. 5, https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/P-EBT_LO_7.30.pdf.

[19] P.L. 117-2 § 1108. Thirteen states plus Puerto Rico had summer P-EBT plans approved as of June 28, 2021. USDA, “State Guidance on Coronavirus P-EBT,” op. cit.

[20] USDA, “USDA to Provide Critical Nutrition Assistance to 30M+ Kids Over the Summer,” April 26, 2021, https://www.usda.gov/media/press-releases/2021/04/26/usda-provide-critical-nutrition-assistance-30m-kids-over-summer.

[21] USDA has also estimated how many children will qualify and the amount of assistance that could flow to each state. See “Pandemic EBT — Summer 2021,” https://fns-prod.azureedge.net/sites/default/files/resource-files/21-04-24-p-ebt-final.pdf.

[22] USDA, “State Guidance on Coronavirus P-EBT,” op. cit.

[23] Implementation of P-EBT for the 2020-2021 school year was more complicated than for the 2019-2020 school year because many schools operated hybrid programs that combined in-person with remote instruction and states had to determine the extent to which students had access to meals at school. States are still submitting summer P-EBT plans because they generally turned to those after USDA approved their school-year plan and they began implementation. Developing and implementing summer EBT for future summers would be much simpler.

[24] White House, “Fact Sheet: The American Families Plan,” April 28, 2021, https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2021/04/28/fact-sheet-the-american-families-plan/.