About 2 Million Parents and Young Children Could Be Turned Away From WIC by September Without Full Funding

End Notes

[1] Katie Bergh and Zoë Neuberger, “Hundreds of Thousands of Young Children and Postpartum Adults Would Be Turned Away from WIC under House and Senate Funding Levels,” CBPP, July 26, 2023, https://www.cbpp.org/research/food-assistance/hundreds-of-thousands-of-young-children-and-postpartum-adults-would-be.

[2] Steven Carlson and Zoë Neuberger, “WIC Works: Addressing the Nutrition and Health Needs of Low-Income Families for More Than Four Decades,” CBPP, updated January 27, 2021, https://www.cbpp.org/research/food-assistance/wic-works-addressing-the-nutrition-and-health-needs-of-low-income-families.

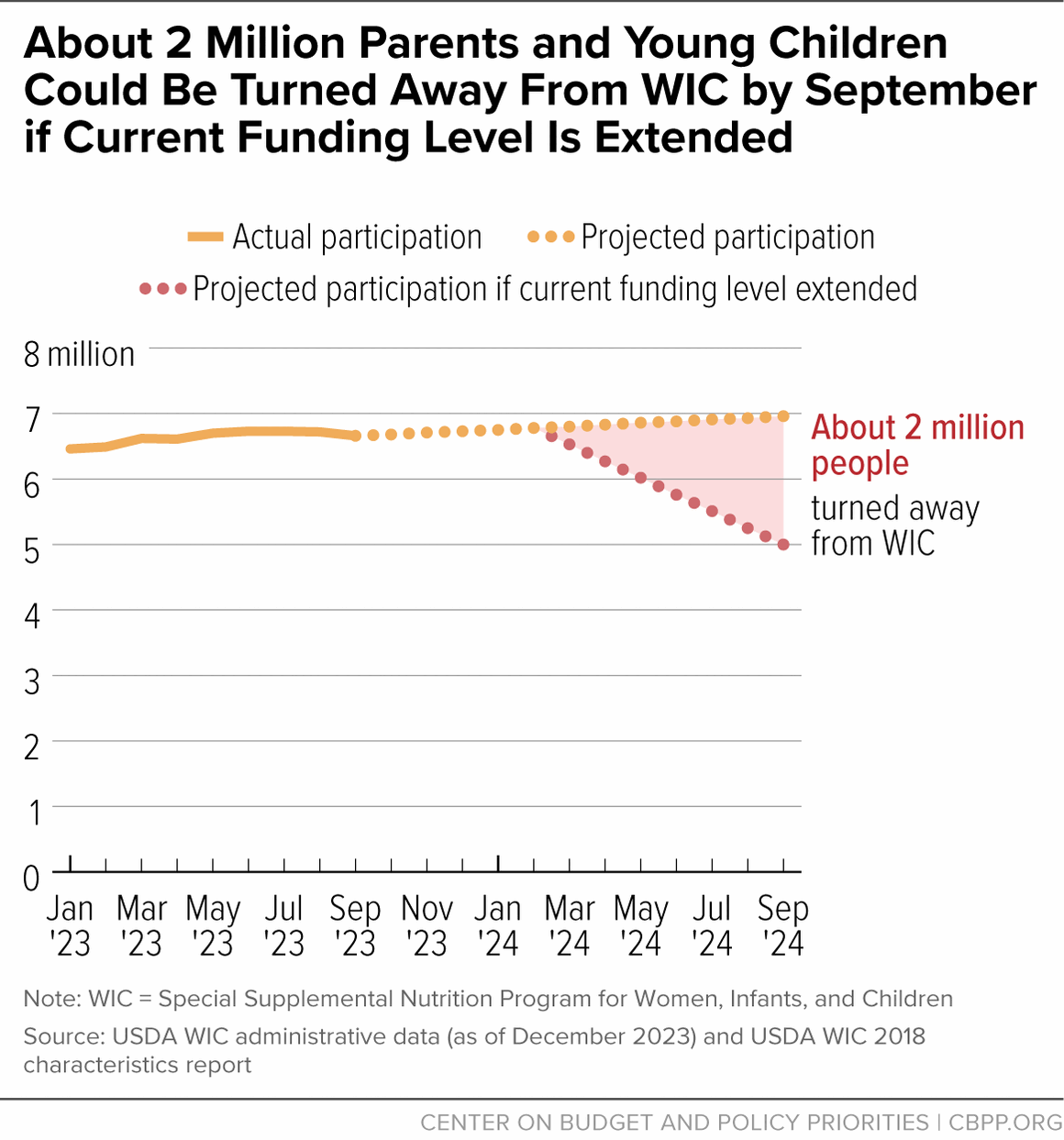

[3] Our estimates assume that WIC’s $150 million contingency fund is spent. They are based on WIC participation data available at https://www.fns.usda.gov/pd/wic-program and administrative data in Food and Nutrition Service, U.S. Department of Agriculture, “WIC Participation and Program Characteristics 2018 Final Report,” May 2020, https://fns-prod.azureedge.us/sites/default/files/resource-files/WICPC2018.pdf. Despite a modest decline in participation in September 2023, which likely resulted from the prospect of a government shutdown, we assume participation will resume its gradual increase over the course of fiscal year 2024.

[4] This authority was established in Sec. 118 of the Continuing Appropriations Act, 2024 and Other Extensions Act (P.L. 118-15) and extended by the Further Continuing Appropriations Act, 2024 (P.L. 118-22). The current funding level is modestly higher than the fiscal year 2023 level because these continuing resolutions did not include a $315 million rescission of unspent prior-year WIC funds that applied at the start of fiscal year 2023.

[5] Marcia Brown and Meredith Lee Hill, “Food aid for low-income mothers, babies becomes spending flashpoint,” Politico, November 21, 2023, https://www.politico.com/news/2023/11/21/food-aid-wic-funding-00128172.

[6] Our estimates assume all states implement waiting lists at the beginning of March and reduce participation by the same number of people each month between March and September 2024. Some states might be able to implement waiting lists in February but, because states have not implemented waiting lists in more than 25 years and some data systems would need to be reconfigured to accommodate waiting lists, other states might not be able to start waiting lists until April or later. States would also likely curtail all outreach to potentially eligible families or participants who miss appointments.

[7] If there is insufficient funding, states may discontinue benefits for current participants in the midst of a certification period with 15 days’ notice but only if they enroll no new applicants or reapplicants, including even the most medically at risk. States would likely take this step only as a last resort. See 7 C.F.R. 246.7(j)(9) and 7 C.F.R. 246.7(e)(4). States may shorten certification periods for children and breastfeeding participants from one year to six months, which would increase the number of participants who could be placed on a waiting list when their certification period ends. See 7 C.F.R. 246.7(g).

[8] The WIC funding level included in the Senate-passed agriculture appropriations bill is modestly higher than extending the current level would be but still about $700 million lower than the necessary amount. The bill advanced by the House Appropriations Committee cuts WIC funding more deeply than extending the current level would and would slash fruit and vegetable benefits for remaining WIC participants. For more information on these bills see Bergh and Neuberger, op. cit.

[9] The nutrition risk priority system and categories are described in 7 C.F.R. 246.7(e)(4).

[10] States are permitted to prioritize serving younger children over older children, but most states’ risk priority systems do not distinguish between young children who are older than infants, which means that 1-year-olds would be turned away along with older toddlers and preschoolers. Even if states did prioritize by age, they would likely have to turn away children as young as 2 years old to sufficiently reduce participation. States are also permitted to prioritize lower-income applicants and reapplicants. These estimates assume that states prioritize only based on participant category (such as breastfeeding) and nutrition risk.

[11] Brynne Keith-Jennings, “Boosting SNAP: Benefit Increase Would Help Children in Short and Long Term,” CBPP, July 30, 2020, https://www.cbpp.org/blog/boosting-snap-benefit-increase-would-help-children-in-short-and-long-term.

[12] Katie Bergh and Lauren Hall, “Looming WIC Shortfall Would Jeopardize Access to WIC’s Proven Benefits and Disproportionately Harm Black and Hispanic Families,” CBPP, October 26, 2023, https://www.cbpp.org/blog/looming-wic-funding-shortfall-would-jeopardize-access-to-wics-proven-benefits-and.

[13] See 7 U.S.C. 2257. The Secretary of Agriculture most recently used this authority for a transfer to WIC in September 2023 to prevent an unforeseen funding shortfall at the end of fiscal year 2023 due to higher-than-expected food costs and participation. This authority limits the amount of the transfer to no more than 7 percent of the appropriation for the recipient account, “except in cases of extraordinary emergency.”

[14] Food and Nutrition Service, U.S. Department of Agriculture, “National and State Level Estimates of WIC Eligibility and WIC Program Reach in 2021,” November 2023, https://www.fns.usda.gov/research/wic/eligibility-and-program-reach-estimates-2021.