The 2017 tax cuts enacted under President Trump were regressive and expensive, and their benefits to the wealthy failed to trickle down as promised. Looking at the pass-through deduction specifically, more than half of its benefits flow to the richest households,[1] and extending this provision beyond its scheduled expiration at the end of 2025 would cost over $700 billion over the decade that would follow.[2] No provision of the 2017 tax cuts highlights the need for a course correction in 2025 more than the pass-through deduction, and yet some congressional Republicans are doubling down: House and Senate Republicans recently introduced bills that would permanently extend the deduction. Any extension should be rejected this year, next year, and finally, in 2025.

The 2017 tax law created a new deduction for certain income that owners of pass-through businesses (partnerships, S corporations, and sole proprietorships) report on their individual tax returns; previously, that income was generally taxed at the same rates as wage and salary income. Heavily skewed in favor of high-income people, the deduction effectively cuts the top tax rate on this pass-through income by 20 percent, to 29.6 percent, compared to the 37 percent top rate that applies to wages and salaries.

In addition to its skewed benefits and high cost, the deduction encourages wealthy taxpayers to game the system as they maneuver to qualify for it, sometimes illegally. This represents one of the worst kinds of tax policy: one that elicits little change in real economic activity but sparks a reclassification of the tax consequences of existing activity. And in the process it weakens the integrity of the entire income tax and drains the Treasury.

Evaluation of the pass-through deduction is often obfuscated from two directions. The technical complexity of the provision and of partnership taxation more generally often perplexes non-tax-experts, while claims that pass-throughs are “small businesses” deserving special treatment oversimplify — and mislead. To clarify how to think about the pass-through deduction specifically as well as the overall tax policy choices before policymakers, consider the following example.

Car dealerships are among the five largest industries for millionaire-owned pass-throughs (ranked by profits) and typify the type of pass-through entity owned by the top 0.1 percent.[3] The average cost of a new car today is about $48,000.[4] The question for policymakers is whether they want to keep giving wasteful tax cuts to dealership owners or instead enact policies that would help dealership employees or any family for whom that $48,000 would be a reach, or unheard of.

A far better tax policy approach is one that helps families who otherwise may struggle to buy a car, put food on the table, or afford to take their children to the doctor when they’re sick — that is, a tax code that raises more needed revenues, is more progressive and equitable, and supports investments that make the economy work so that everyone can set themselves up to thrive.

Though the 2017 law’s proponents often identify small businesses as the pass-through deduction’s intended beneficiaries, the deduction is heavily skewed in favor of high-income people for the following reasons:

- Wealthy people are much more likely to have pass-through income than other people. For example, people in the top 1 percent are over 50 times more likely to have partnership income than people in the bottom 50 percent of the income spectrum.[5]

- The amount of pass-through income that wealthy pass-through owners have is an order of magnitude greater than that of owners with more modest incomes. For example in 2018, the first year the pass-through deduction was in effect, the average deduction taken was roughly $8,000 compared to the $1-million-plus average pass-through deduction taken by the 15,000 taxpayers who have incomes above $10 million.[6]

- Because the provision is designed as a tax deduction, as opposed to a tax credit, its relative value is much higher for wealthy pass-through owners. The value of a tax deduction equals the deduction amount times the taxpayer’s tax rate. This means, for example, the same $1,000 pass-through deduction is worth $150 to someone with a modest income in the 15 percent bracket but $370 for a rich person in the current top 37 percent bracket.

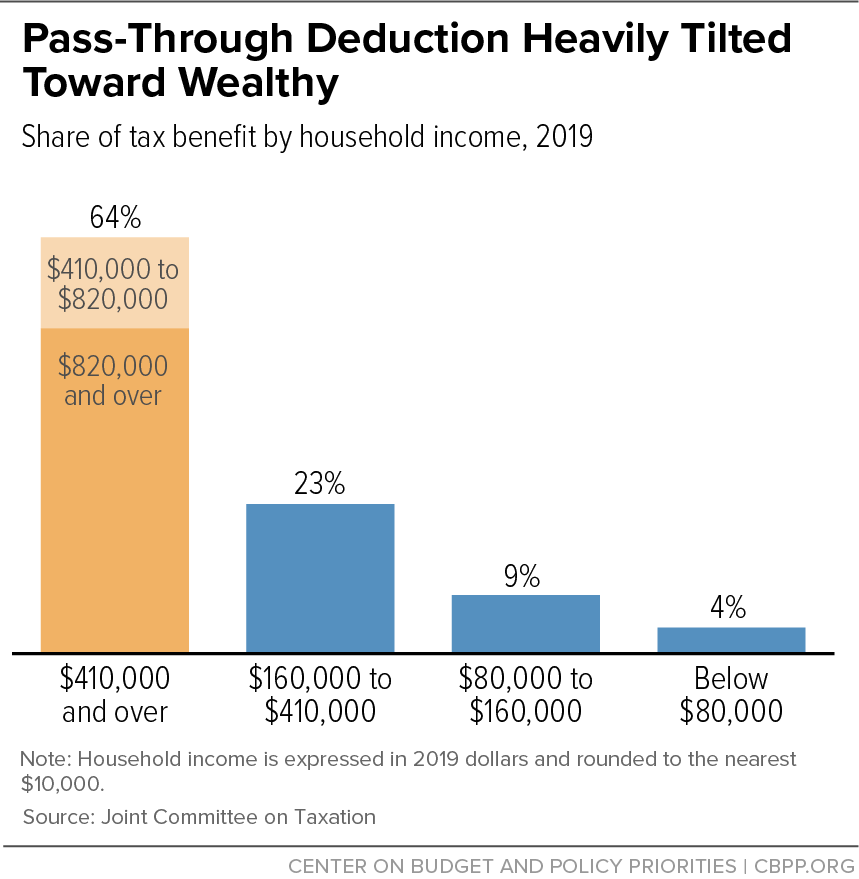

In 2019 more than half of the benefit flowed to households with $820,000 or more in income and nearly two-thirds went to those with more than $400,000, according to the Joint Committee on Taxation.[7] (See Figure 1.)

Pass-Through Deduction Is Costly and Its Benefits Don’t Trickle Down

Permanently extending the pass-through deduction would cost over $700 billion over the decade from 2026 to 2035.[8]

Proponents argued that the pass-through deduction would generate economic rewards for people who work at these businesses and for the economy overall, which would exceed its large cost. Yet evidence is lacking for any discernible trickle-down benefit, let alone one sufficient to justify the highly regressive costs. A group of economists, including from Treasury and the Federal Reserve, found no evidence that the deduction provided any boost in economic activity — no additional investment, jobs, or higher wages for employees of pass-through businesses.[9]

While this research was necessarily short-term in nature (the deduction was enacted in 2017), another recent study followed pass-through businesses and their workers for several years after a tax change and found a broadly similar result — that the change only affected owners and higher-paid workers and not other workers or broader economic activity at impacted companies.[10] This research looked at the effect of raising taxes on pass-through owners using the 2012 increase in the top marginal tax rate (which applied to pass-through income).

It found that over 80 percent of the tax increase was borne by the business owners and that the small share of the tax borne by employees was concentrated among those in the top 30 percent of the earnings distribution within companies; most workers were unaffected. Meanwhile, the study found no effects on sales, employment, or productivity at businesses subject to the higher top tax rate.

This suggests that, just as the pass-through deduction has had no discernible economic upside, its expiration would have little to no economic downside. In fact, its expiration would free up more than $700 billion over ten years to use on deficit reduction or important investments with proven economic benefits for families, such as expanding the Child Tax Credit, helping people afford rent, and making quality child care and pre-K more affordable and accessible.

The pass-through deduction has not elicited much change in real economic activity, but it has encouraged reclassification of the tax consequences of existing activity. This reclassification, which can verge into outright evasion, will continue to happen and likely increase unless policymakers let this poorly designed provision expire.

One form of partnership compensation that doesn’t benefit from the deduction, “guaranteed payments,” immediately fell by roughly 30 percent in 2018.[11] It stayed low in 2019 as owners and their tax advisors took advantage of the arbitrary distinctions between types of income in the deduction’s complicated rules.[12] Partnerships often make guaranteed payments to partners, which are analogous to salaries. But if the partnership instead distributes the same amount of payments to partners as profits, those profits can qualify for the deduction. Partnerships could increase their deductions simply by changing the distribution routes of the same income.

If the deduction is made permanent, more and more income will be reclassified as pass-through income, that is, this tax distortion will grow and grow. The Tax Policy Center estimated that this type of gaming could account for around 16 percent of the total revenue loss from extending the deduction.[13]

The large accounting changes that the deduction promotes often have no economic basis, are just a drain on the Treasury, and can even be illegal. Complex and valuable tax benefits like the pass-through deduction encourage taxpayers to push the boundary between lawful tax avoidance — itself engaged in by people with access to well-paid tax advisors — and unlawful evasion.

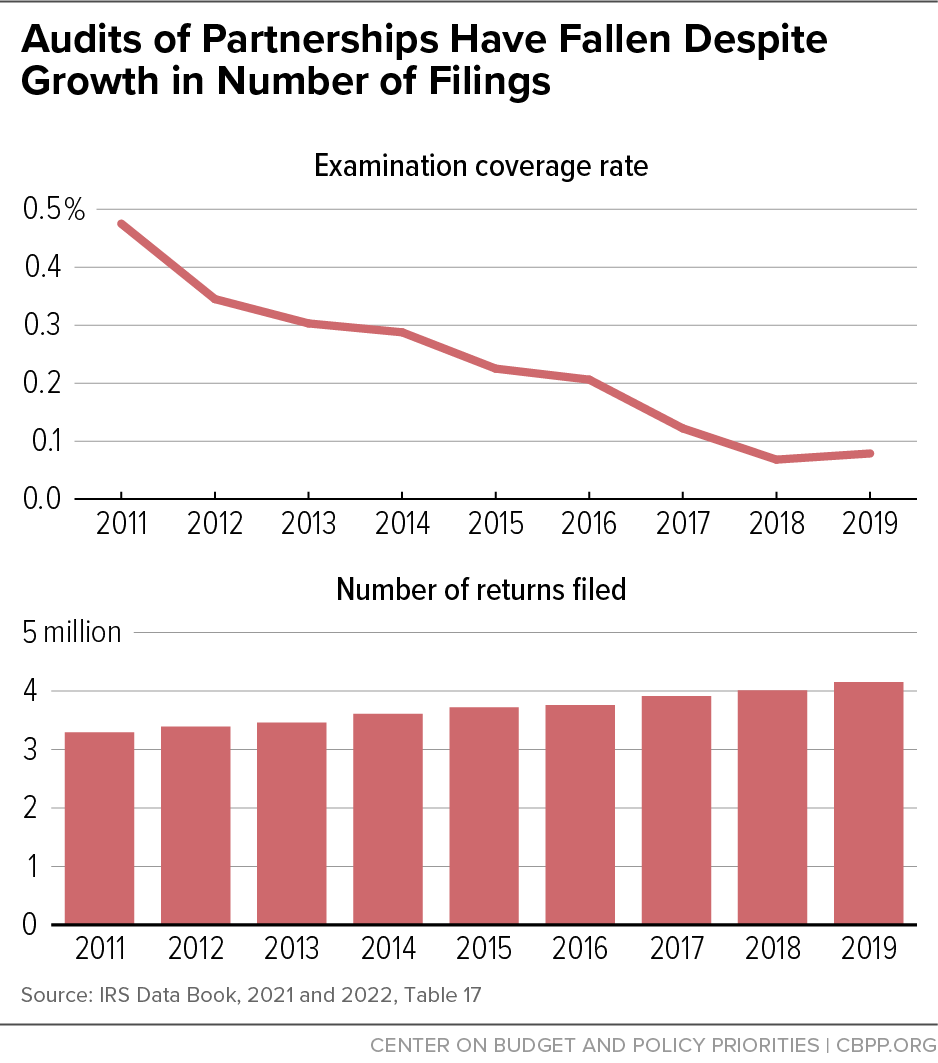

And plummeting pass-through audit rates give them more leeway to do so. Fewer than 0.1 percent of partnerships, for example, are audited each year.[14] (See Figure 2.) This weakens the integrity of the entire income tax and adds new burdens to an IRS that has struggled to adequately combat sophisticated tax evasion schemes involving pass-through entities. The pass-through deduction should expire as scheduled in 2025.[15]

Instead of extending ineffective and costly tax cuts benefiting the wealthy, policymakers should raise progressive revenues and use them to finance high-return public investments that can boost growth. For example, compelling research finds that infants in families with lower incomes who receive more support from child-related tax benefits go on to have higher test scores, high school graduation rates, and earnings into young adulthood,[16] supporting a strong economy and helping position themselves to thrive.