The House Republican tax bill would increase the maximum Child Tax Credit (CTC) from the current $1,000 to $1,600 per child, but only some families would benefit. Republicans have highlighted this proposal as their plan’s signature benefit for working families, but it would completely exclude 10 million children whose parents work for low pay — about 1 in 7 of all U.S. children in working families, including thousands of children in every state. Another 12 million children in working families would receive less than the full $600-per-child increase in the credit (in most cases, much less). Altogether, about 1 in 3 children in working families would either be excluded entirely or only partially benefit from the CTC increase.[1]

The House Republicans’ proposal would partially or entirely exclude more than 25 percent of children in working families in almost every state. In 12 states, at least 40 percent of these children would be excluded: Alabama, Arizona, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, Nevada, New Mexico, South Carolina, Tennessee, and Texas.

House Republicans’ decision to partially or entirely exclude these 23 million children from their proposed CTC expansion is especially striking because they also chose to newly extend the CTC (in whole or in part) to families with higher incomes. Married couples with two children with incomes between $150,000 and $294,000 would become newly eligible for the credit.

The House bill would also cut or eliminate the CTC for roughly 1 million immigrant children in low-income families, most of them Dreamers, creating further economic hardship for this group of families. (See text box.)

Even as the House tax plan excludes millions of children from the CTC expansion, it provides large new tax cuts for the wealthiest families and profitable corporations while increasing deficits by $1.5 trillion over the next decade. Congressional Republicans are likely to use rising deficits as an excuse to come back as soon as next year and seek large budget cuts in areas such as Medicaid, food assistance for struggling families, and education. These cuts will be borne heavily by the same families that receive no or only modest benefits from the tax bill, leaving them worse off when the tax cuts and subsequent budget cuts are considered together.

The CTC now provides a maximum tax credit of $1,000 per eligible child under age 17. The credit is “partially refundable,” meaning that it is partly, but not entirely, available to many low-income families. Specifically, the refundable portion of the CTC is limited to 15 percent of a family’s earnings over $3,000. Thus, a single mother with two children and earnings of $10,000 is eligible for a CTC of $1,050, or $525 per child, rather than for the $2,000 ($1,000 per child) that a middle-income family with two children receives. Because of the credit’s slow phase-in for working families with low incomes, families with two children do not receive the full credit of $1,000 per child until their earnings reach $16,333. The poorest children consequently qualify for only a very small CTC or none at all.

The House tax plan proposes to increase the maximum CTC to $1,600 per child. But it would not increase the refundability of the existing credit, which would still be limited to 15 percent of earnings over $3,000. Moreover, as explained below, the House bill limits low-income families’ access to its CTC increase, capping the amount of the credit that is refundable at $1,100 next year, indexed for inflation going forward. The maximum refundable amount would not reach $1,600 until around 2036.

While doing nothing to strengthen the CTC for the lowest-income working families, the plan calls for increasing the income levels at which the CTC begins to phase out for higher-income families, thereby making more families with six-figure incomes eligible for the credit.

To see how the House bill’s CTC expansion would fully or partially exclude children in low-income working families, consider two examples.

- A single mother with two children working full time as a home health aide at the federal minimum wage earns $14,500. Based on her earnings, her total refundable credit is capped at $1,725, less than the current-law $1,000-per-child credit. Thus, she would receive no benefit from the higher maximum credit under the House proposal.

- A married couple with two children earns $24,000. Based on their earnings, this couple could qualify for a total refundable credit of $3,150, so it would seem they could receive almost the full benefit of the House bill’s $600-per-child CTC increase. But because the bill would cap refundability at $1,100 per child, indexed for inflation, the family would benefit by only $100 per child ($200 total) next year. This is because their income tax liability before the CTC is not large enough to qualify them for a bigger credit.

We estimate that 10 million children in low-income working families (about 1 in 7 of all U.S. children in working families) would be entirely excluded from the CTC increase, with situations similar to the first example above.[2] Another 12 million children would benefit by less than the full $600 increase in the credit; the majority of these children are in families that would benefit by less than $200 per child in 2018.[3] In total, 23 million children — or about 1 in 3 children in working families — would be partially or fully excluded from the CTC increase. This includes:

- 6.0 million children in working-poor families, 1.2 million of whom live in deep poverty (i.e., below half the poverty line);

- 8.4 million children under age 6; and

- 8.5 million Latino children, 7.8 million white children, 4.5 million African American children, and 600,000 Asian children.

(See Table 1. For detailed methodology and state-by-state estimates of children who would be excluded, see the Appendix.)

| TABLE 1 |

|---|

| |

Fully excluded (millions) |

Partially excluded (millions) |

Fully or partially excluded (millions) |

|---|

| Latino |

3.7 |

4.8 |

8.5 |

| White (non-Latino) |

3.3 |

4.4 |

7.8 |

| African American (non-Latino) |

2.3 |

2.2 |

4.5 |

| Asian (non-Latino) |

0.2 |

0.4 |

0.6 |

| Other |

0.7 |

0.6 |

1.3 |

| Total |

10.3 |

12.5 |

22.7 |

| Including |

|

|

|

| Under age 6 |

3.9 |

4.6 |

8.4 |

| In poverty |

3.8 |

2.2 |

6.0 |

| In deep poverty (below half the poverty line) |

1.1 |

0.2 |

1.2 |

The average income of working families with children that would be partially or entirely left out of the CTC increase is $22,000. Among these working families, two-thirds include at least one parent who works full time for most of the year.[4] The parents in these families work in a range of occupations, many of which pay low or modest wages (see Table 2).

| TABLE 2 |

|---|

| |

Number of working parents |

|---|

| Sales |

1,279,000 |

| Office and administrative support |

1,247,000 |

| Food preparation and serving |

1,130,000 |

| Building and grounds cleaning and maintenance |

1,058,000 |

| Construction and extraction |

1,002,000 |

| Transportation and material moving |

980,000 |

| Manufacturing |

885,000 |

| Personal care and service |

866,000 |

| Health care support |

630,000 |

In almost every state, at least 1 in 10 children in working families would be completely excluded from the House bill’s CTC increase (see Appendix Table 1). And in almost every state, at least 1 in 4 children in working families would either be excluded or receive less than the full increase.

But in many states, generally higher-poverty, lower-wage states, a much larger share of children would be left out. In 12 states, at least 40 percent of children in working families would receive less than the House bill’s touted $600-per-child CTC increase: Alabama, Arizona, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, Nevada, New Mexico, South Carolina, Tennessee, and Texas.

The children who would be fully or partially excluded from the proposed CTC changes are those whose families experience the greatest financial hardship, and those for whom additional help would likely make the most difference in helping make ends meet and creating a more stable environment for children. They are also those for whom, extensive research indicates, a CTC boost could make the most difference over the long run.

- Research indicates that income from the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC)[5] and the CTC yields benefits for many children at virtually every stage of life.[6] Starting from infancy — when larger refundable tax credits have been linked with more prenatal care, less maternal stress, and signs of better infant health — children who benefit from tax-credit expansions have been found to do better than similar children who don’t benefit. They have higher odds of finishing high school and therefore going on to college, and the added income from the credits has been linked to significant increases in college attendance by making college more affordable for families with high-school seniors. Researchers note that the education and skill gains associated with the EITC and CTC are likely to keep paying off through higher earnings and employment in adulthood.

- Research also shows that income gains from sources that include tax credits matter the most for the poorest children. “[T]here is very strong evidence that increases in income have a bigger impact on outcomes for those at the lower end of the income distribution,” a systematic review of the research literature on the effects of income during childhood, conducted by researchers at the London School of Economics and Political Science, concluded. All 13 of the relevant studies the researchers examined supported this finding.[7] One study found, for example, that the EITC’s effect in increasing children’s math and reading test scores was almost three times larger for the lowest quartile of its sample than for other low- and moderate-income families.[8] These findings are consistent with the view of many experts that the adverse effects of poverty on children are most pronounced for children who live below half of the poverty line.[9]

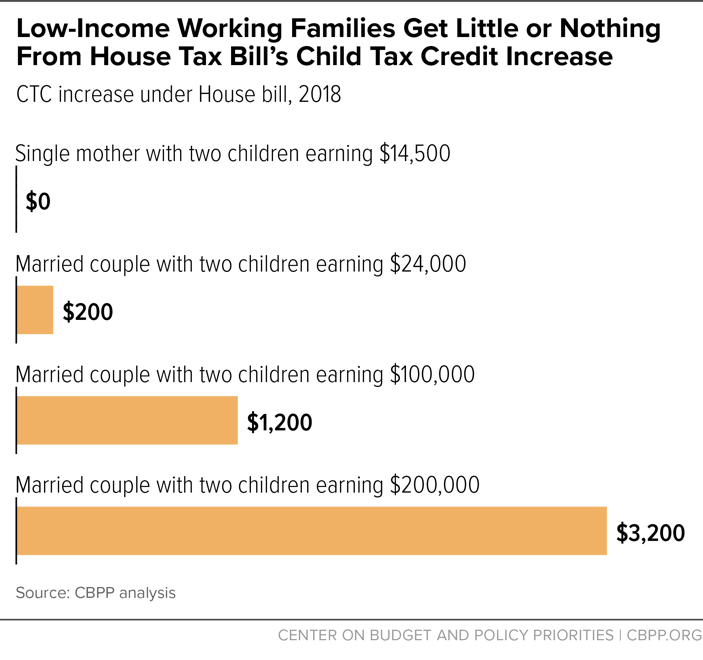

While the lowest-income working families would get nothing from the CTC proposal in the House tax bill, those who earn substantial salaries would qualify for the maximum CTC boost (see Figure 1). Of particular note, the proposal would increase the income level at which the CTC begins to phase out, making more filers with six-figure incomes eligible for the credit. For example:

- Married couples with two children and incomes between $150,000 and $294,000 would become newly eligible for a CTC. (Currently, the CTC phases out at $150,000 for married filers with two children.)

- Married couples with two children and incomes between $115,000 and $230,000 would become newly eligible for the maximum CTC. A married couple with two children earning $200,000 would receive a $3,200 CTC increase; its CTC would rise from zero today to $3,200 under the plan.

Republican Senator Marco Rubio rightly criticized the House bill for doing too little to help low-income working families.[10] A proposal from Senator Rubio and Senator Mike Lee, also endorsed by a number of other Republican senators, would modestly increase the amount of the CTC that would be refundable, in addition to providing a substantial increase in the maximum credit.[11] The proposal thus would provide some increase in the CTC to the poorest working families. Even so, those families still would receive only a fraction of the proposed increase in the maximum per-child credit and much smaller increases than those families higher up the income scale.

The Rubio-Lee proposal would change the refundable amount of the CTC to 15.3 percent of a family’s total earnings — that is, it would start phasing in with the first dollar of earnings — instead of the credit equaling 15 percent of earnings over $3,000, as at present. The impact of these changes would be positive but modest. For example, if the Rubio-Lee refundability proposal were added to the House Republican bill, a single parent with two children working full time at the federal minimum wage, earning $14,500 annually, would receive a CTC increase of $494, rather than zero as under the House bill. But this would be only a quarter of the $2,000 CTC increase that two-child families at higher income levels would receive under the Rubio-Lee CTC design.

CTC reforms could be designed to strengthen the credit for lower-income families. The current CTC could be made fully refundable so families with very low or no earnings could receive the full CTC. A more modest improvement would begin phasing in the credit with the first dollar of earnings, as the Rubio-Lee proposal would do, and raise the phase-in rate significantly above 15 percent, at least for families with a young child, so that working-poor families would receive a more adequate CTC. The amount of the maximum CTC could also be increased further, especially for young children. Children under 6 tend to be poorer than other children, and the research literature is particularly clear that young children would benefit significantly from the additional income that such CTC improvements could provide. These and other CTC improvements are included in bills introduced by Rep. Rosa DeLauro, Senators Sherrod Brown and Michael Bennet, and other lawmakers.[12]

Improvements like these would substantially improve the CTC proposal in the House tax bill. But they would not alter the two overriding shortcomings in the overall plan: its heavy tilt toward the highest-income households and profitable corporations, and its impact in substantially increasing budget deficits and debt. Rising deficits in turn would lead to increased pressure to make deep budget cuts in areas such as health care, food assistance for struggling families, and education — cuts that would fall heavily on low- and middle-income families and render them net losers, even if the plan’s CTC provisions are strengthened.

Overall, the House tax bill is heavily skewed toward high-income households and profitable corporations. When fully in effect, 38 percent of its benefits would go to the 0.3 percent of filers with annual incomes over $1 million, Joint Tax Committee estimates show.[13] Even a substantially improved CTC would only modestly mitigate this extreme tilt.

In addition to largely excluding millions of children from its CTC increase, the House tax bill would harm roughly 1 million low-income children in working families by denying them the Child Tax Credit (CTC) because they lack a Social Security Number (SSN).

People who work in the United States must pay taxes on their income, regardless of their immigration status. Immigrant workers lacking an SSN file their income tax return using an ITIN. ITIN filers are generally subject to the same tax rules as other filers and are eligible for the same tax benefits, such as the CTC (including the “refundable” part that goes to those who earn too little to owe federal income tax). The House bill, however, would allow filers to claim the CTC (both the refundable and non-refundable portions) only for children who have an SSN rather than an ITIN.

Proponents describe this CTC change as an “anti-abuse” measure. It isn’t: it’s a major eligibility cut for working families who are doing nothing wrong by claiming the credit. Roughly 1 million children, most of them in low-income working families, would lose eligibility for the CTC, Pew Hispanic Center estimates suggest. These children are overwhelmingly Dreamers — undocumented children who were brought to the United States by their immigrant parents. Their parents use the credit to help feed their families, keep a roof over their heads, and offset income taxes; and it goes only to working families, including many in which the parents work in tough jobs that often lack basic protections that most other workers take for granted. Many of these individuals pick crops, clean houses and offices, or care for other Americans’ children or grandparents.

The children who would lose the tax credit will continue to be part of our communities and the economy as adults. All Americans thus have a stake in ensuring that these children get the resources they need to become productive workers. Taking the CTC’s income away from poor children would not only increase poverty and hardship immediately, but would also make it less likely that these children will finish high school and go on to college, recent research indicates.a The CTC changes thus could increase poverty both today and in the future.

The IRS is already acting to prevent error and fraud concerning ITINs and the CTC, and Congress took action as well. But the CTC provision in the House bill isn’t designed to strengthen tax compliance. It’s an attempt to deny the credit to 1 million children in immigrant families.

a Arloc Sherman and Tazra Mitchell, “Economic Security Programs Help Low-Income Children Succeed Over Long Term, Many Studies Find,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, July 17, 2017, https://www.cbpp.org/research/poverty-and-inequality/economic-security-programs-help-low-income-children-succeed-over.

Congressional leaders and the Trump Administration have made clear their plans to seek large budget cuts after the tax bill is completed. Congressional leaders have pointed to existing budget deficits — even before any new tax cuts are enacted — to justify proposed steep cuts in basic assistance programs on which struggling families rely to obtain health care and help make ends meet, as well as cuts in a broad set of programs important to children’s future prospects, such as education and job training. If such cuts were made to offset the cost of the tax cuts, most families with children would likely end up worse, rather than better, off. [14]

| APPENDIX TABLE 1 |

|---|

| |

Fully Left Out |

Receive Only Partial Benefit |

Fully or Partially Left Out |

|---|

| |

Number |

Percent |

Number |

Percent |

Number |

Percent |

| US Total |

10.3 million |

16 |

12.5 million |

20 |

22.7 million |

36 |

| Alabama |

181,000 |

19 |

194,000 |

21 |

375,000 |

40 |

| Alaska |

22,000 |

13 |

20,000 |

12 |

43,000 |

26 |

| Arizona |

264,000 |

19 |

310,000 |

22 |

574,000 |

41 |

| Arkansas |

119,000 |

20 |

145,000 |

24 |

264,000 |

44 |

| California |

1,336,000 |

17 |

1,719,000 |

22 |

3,055,000 |

39 |

| Colorado |

134,000 |

12 |

203,000 |

18 |

337,000 |

30 |

| Connecticut |

67,000 |

10 |

88,000 |

13 |

156,000 |

23 |

| Delaware |

29,000 |

16 |

28,000 |

16 |

57,000 |

32 |

| Dist. of Columbia |

14,000 |

16 |

16,000 |

17 |

30,000 |

33 |

| Florida |

586,000 |

17 |

818,000 |

23 |

1,404,000 |

40 |

| Georgia |

422,000 |

20 |

453,000 |

21 |

874,000 |

41 |

| Hawaii |

31,000 |

11 |

49,000 |

18 |

81,000 |

29 |

| Idaho |

56,000 |

15 |

93,000 |

24 |

149,000 |

39 |

| Illinois |

388,000 |

15 |

483,000 |

18 |

870,000 |

33 |

| Indiana |

230,000 |

17 |

281,000 |

20 |

511,000 |

37 |

| Iowa |

86,000 |

13 |

109,000 |

17 |

195,000 |

30 |

| Kansas |

90,000 |

14 |

126,000 |

19 |

216,000 |

33 |

| Kentucky |

150,000 |

18 |

169,000 |

20 |

319,000 |

38 |

| Louisiana |

194,000 |

21 |

186,000 |

20 |

380,000 |

41 |

| Maine |

29,000 |

13 |

39,000 |

17 |

69,000 |

31 |

| Maryland |

129,000 |

11 |

172,000 |

14 |

302,000 |

25 |

| Massachusetts |

121,000 |

10 |

148,000 |

12 |

269,000 |

22 |

| Michigan |

325,000 |

17 |

344,000 |

18 |

669,000 |

35 |

| Minnesota |

134,000 |

12 |

169,000 |

15 |

303,000 |

26 |

| Mississippi |

133,000 |

22 |

141,000 |

24 |

275,000 |

46 |

| Missouri |

198,000 |

16 |

220,000 |

18 |

418,000 |

34 |

| Montana |

31,000 |

16 |

36,000 |

18 |

67,000 |

34 |

| Nebraska |

61,000 |

14 |

77,000 |

18 |

138,000 |

32 |

| Nevada |

98,000 |

17 |

139,000 |

24 |

238,000 |

41 |

| New Hampshire |

20,000 |

8 |

31,000 |

13 |

51,000 |

21 |

| New Jersey |

209,000 |

12 |

252,000 |

14 |

461,000 |

26 |

| New Mexico |

91,000 |

21 |

105,000 |

25 |

196,000 |

46 |

| New York |

569,000 |

16 |

664,000 |

18 |

1,233,000 |

34 |

| North Carolina |

355,000 |

18 |

437,000 |

22 |

792,000 |

40 |

| North Dakota |

17,000 |

11 |

18,000 |

12 |

36,000 |

23 |

| Ohio |

389,000 |

17 |

409,000 |

18 |

798,000 |

35 |

| Oklahoma |

142,000 |

17 |

184,000 |

22 |

326,000 |

39 |

| Oregon |

125,000 |

17 |

143,000 |

19 |

268,000 |

36 |

| Pennsylvania |

313,000 |

14 |

385,000 |

17 |

699,000 |

30 |

| Rhode Island |

24,000 |

13 |

32,000 |

17 |

55,000 |

30 |

| South Carolina |

176,000 |

19 |

197,000 |

21 |

373,000 |

41 |

| South Dakota |

24,000 |

13 |

34,000 |

18 |

59,000 |

31 |

| Tennessee |

248,000 |

19 |

269,000 |

21 |

518,000 |

41 |

| Texas |

1,184,000 |

19 |

1,383,000 |

22 |

2,567,000 |

41 |

| Utah |

99,000 |

12 |

153,000 |

18 |

252,000 |

30 |

| Vermont |

12,000 |

12 |

16,000 |

15 |

28,000 |

27 |

| Virginia |

194,000 |

12 |

257,000 |

16 |

451,000 |

27 |

| Washington |

179,000 |

13 |

251,000 |

18 |

430,000 |

30 |

| West Virginia |

57,000 |

18 |

59,000 |

19 |

116,000 |

37 |

| Wisconsin |

158,000 |

14 |

197,000 |

17 |

355,000 |

31 |

| Wyoming |

13,000 |

11 |

19,000 |

15 |

32,000 |

26 |

This analysis examines families (that is, tax filing units), children, and parents left behind by the Child Tax Credit (CTC) proposal introduced by House Republicans in November 2017.[15] We assess the CTC proposal (namely, increasing the credit’s non-refundable portion to $1,600 per child, while limiting the refundable portion to $1,000 per child adjusted annually for inflation and set at $1,100 in 2018) alone, without regard to the bill’s other tax changes.[16]

The analysis is based on data from the Tax Policy Center (TPC) and the Census Bureau. CBPP used TPC data for the nationwide number of working families and children fully left out of the CTC expansion because their earnings are too low to benefit at all from the proposal.[17] We used the Census Bureau’s March 2017 Current Population Survey (CPS) public-use file to estimate the nationwide number of working families and children partially left out of the expansion because their incomes are too low to receive the full $600-per-child benefit.[18] Family incomes (and corresponding tax liabilities) are adjusted for inflation to approximate 2018 levels.

Characteristics of children left out are estimated using the CPS-based share of children left out in each demographic group, applied to the national totals. Those fully left out and those partially left out are calculated separately.

Numbers and characteristics of working parents left out are estimated using CPS-based average numbers of parents per 100 left-out families, applied to the national family totals.[19] (Again, those fully left out and partially left out are calculated separately.)

For state-by-state figures, CBPP used public-use files from the larger American Community Survey (ACS) for 2013 through 2015. We averaged three years of ACS data to further increase the reliability of the state estimates. We used the ACS data to assign each state its estimated share of TPC’s total 10.3 million children fully left out[20] and the number of children partially left out, based on the CPS-derived totals.[21]

In the state table, totals for children in working families include children under age 17 (the age eligible for the CTC) in tax filing units in which the filer or spouse worked one or more weeks. Elsewhere in this analysis, “working” generally refers to tax units with earnings.