The Securing a Strong Retirement Act of 2022 passed the House on March 29 with broad bipartisan support and is expected to garner strong support in the Senate. Unfortunately, its key provisions, which would expand the federal tax subsidies for retirement saving, mainly help people with higher incomes and financially secure retirements — who benefit the most from existing subsidies — and would do little for people with low and moderate incomes, who have much more pressing needs. The bill also relies on timing gimmicks to offset its cost within the ten-year budget window; after the initial decade it would lose significant revenue.

Tax subsidies for retirement savings are one of the largest federal tax expenditures, costing around $380 billion annually.[1] The primary retirement tax subsidies allow people to contribute to accounts such as a traditional 401(k) or IRA plan on a pre-tax basis. That is, taxpayers can defer all taxes on retirement contributions and earnings until they withdraw the money in retirement, at which point it is taxed as ordinary income. With “Roth” IRAs and Roth 401(k)s, the tax treatment is reversed: contributions are made with after-tax income, but neither the growth of the assets in these accounts over time as they produce earnings, nor the withdrawals made in retirement, are subject to tax.

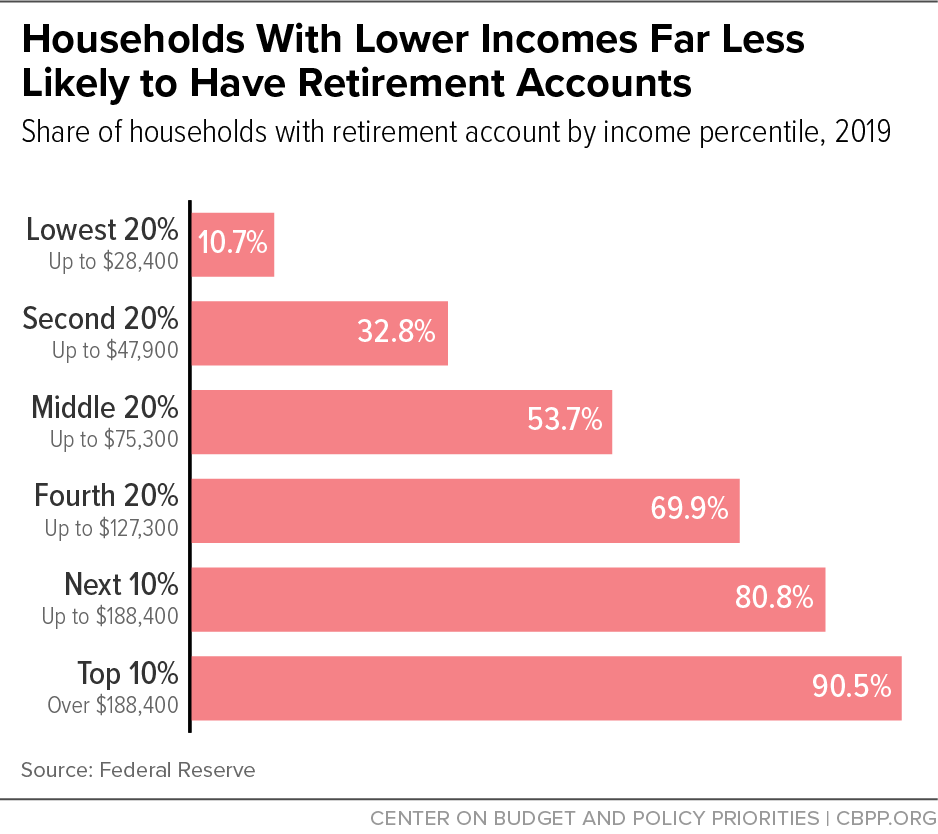

The current subsidies increase income and racial disparities because they are skewed toward people who are affluent and white.[2] Most people with low or moderate incomes do not have retirement savings accounts, and those who do tend to have small balances; high-income people are more likely to have accounts and generally have much larger balances. For example, only about 1 in 10 households in the bottom income quintile and 1 in 3 people in the second quintile have a retirement account at all, compared to 9 in 10 people in the highest-income 10 percent.[3] (See Figure 1.) As for account balances, account holders in the second quintile had a median balance of $17,000 in 2019, compared to $460,000 for account holders in the top 10 percent.[4]

Moreover, high-income households enjoy a larger tax break per dollar of deductible retirement contributions because they are in a higher tax bracket. For example, someone making $80,000 and in the 22 percent tax bracket receives an upfront tax subsidy of 22 cents per dollar of deductible contributions, whereas someone who makes $600,000 and is in the 37 percent bracket receives an upfront subsidy of 37 cents on the dollar.

Retirement accounts and balances are also unequally distributed by race. Some 57 percent of white people have accounts, compared to 35 percent of Black people and 25 percent of Hispanic people.[5] The median balance for white account holders, while a modest $80,000, is more than double the median balance for Black and Hispanic account holders.[6]

The House bill would raise the starting age for “required minimum distributions,” or required annual withdrawals from retirement accounts, from 72 to 75, phased in over the next decade. This means people whose retirements are financially secure without tapping their retirement accounts could eventually leave the accounts untouched for three more years. A small group of affluent people would benefit from deferring tax for those additional years, which also would enable them to transfer more of those tax-subsidized funds to their heirs.[7] The financial services industry would benefit as well, because the change would keep more money in accounts for longer, bolstering their fees; the industry lobbied successfully for a 2019 increase in the age for required minimum distributions (from 70½ to 72) and supports the House bill. According to law professor Michael Doran, “[t]he effect — the only effect — of the repeated relaxations of the required-minimum-distributions rule is to allow higher-income earners to shelter their investments from tax for longer periods.”[8] This provision is the most expensive in the bill, costing $9.6 billion over ten years.

Another major provision of the bill would allow people approaching retirement age to make larger “catch-up” contributions to their accounts. Under current law, the underlying annual contribution limit for 401(k), 403(b), and other similar tax-favored employer-sponsored retirement accounts is $20,500 in 2022, but people age 50 or above with enough money to save this substantial amount can contribute an additional $6,500, for a total of $27,000 of annual tax-favored contributions. The bill would raise that $6,500 limit to $10,000 for 62-, 63-, and 64-year-olds. According to a Vanguard survey of its account holders, only 15 percent of eligible account holders currently make these additional contributions and therefore could potentially benefit from raising the contribution limit; those account holders have higher incomes and larger account balances than those not making the additional contributions allowed for older people.[9] (Over half of them make over $150,000, for example.)

One provision that could modestly help some people with low and moderate incomes would require employers that establish new 401(k), 403(b), and other such salary-reduction plans to automatically enroll employees in such plans and automatically increase the employees’ contribution level over several years, while allowing them to opt out.[10] Over time, this would likely increase the number of people with low or moderate incomes who have retirement accounts. Since low-income workers face low marginal tax rates, however, they would receive a smaller tax break per dollar of deductible retirement contributions than higher-income people. Moreover, while promoting the retirement security of those with low and moderate incomes is a worthy policy goal, all else equal, diverting part of their income into retirement accounts might not always be a net positive for them, as explained below. [11] This is especially true if the amount that those “opted into” the plans are required to save is too high, as may be the case in this proposal.

The bill would also amend the existing saver’s credit, which subsidizes retirement account contributions for those with low or moderate incomes to encourage and help them save for retirement. The bill would increase the number of people who qualify for the maximum $1,000 credit by raising the income limit to qualify.[12] Acknowledging that the saver’s credit is not widely used (only about one-third of workers with less than $50,000 in income even know it exists, according to a recent survey),[13] the bill’s drafters included funds to mount an awareness-raising campaign. But the bill ignores a critical reason why so few people with low and moderate incomes claim the credit: it isn’t refundable, so people who owe no federal income tax — around 76 million households as of 2019[14] — aren’t eligible. The bill’s failure to make the saver’s credit refundable is a glaring omission.

Another significant problem with the bill is that its main revenue offsets are timing gimmicks: while the bill would increase revenues at first, it would lose revenues in later years, increasing deficits and debt after the ten-year budget window.[15] For example, the bill requires that the additional (“catch-up”) retirement contributions older people are permitted to make be designated as contributions to Roth retirement arrangements. This provision would raise revenue over the first ten years because those contributions, much of which would have been made on a pre-tax basis in the absence of this provision, would instead be taxed upfront. But it would lose revenue in later years because withdrawals from those accounts, which under current law would generally be taxed (when withdrawn from non-Roth retirement accounts), would instead be tax free. As a result of this and other similar provisions, the bill is not fully offset in the long term and would increase deficits and debt in future decades.

As noted above, higher retirement savings for a person are better than lower savings, all else equal. But while encouraging more retirement saving — such as by automatic enrollment — can have positive effects, it may also have unintended negative consequences for some people with lower incomes, depending on their circumstances. For example, if an employer provides matching contributions, automatically enrolling lower-income employees in the employer’s plan helps ensure that they get the full benefit of the match — that is, it prevents them from leaving available money from the employer on the table. But diverting part of a low-income person’s paycheck to a retirement account can make it harder for them to meet their immediate basic needs. Keeping themselves and their families housed and making sure children have what they need are often more pressing concerns than retirement savings for households whose budgets are over-stretched, especially if their employers don’t provide matching contributions.

Further, because Social Security replaces a larger share of earnings for low-income retirees than for higher-income retirees, they need less in other savings to maintain their current standard of living in retirement. But their households have needs today, and when those needs aren’t met, families can face real consequences, including eviction and poor health, and children can see their futures shortchanged.

A much better way for policymakers to help families with low and moderate incomes would be to boost their incomes. The House-passed Build Back Better package includes provisions to do exactly that, through a permanently fully refundable Child Tax Credit plus a one-year extension of the American Rescue Plan’s expanded Child Tax Credit and an expanded Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) for adults not raising children in their homes:

- Child Tax Credit: A fully refundable $2,000 Child Tax Credit for children under 17 would reduce child poverty by roughly 20 percent relative to current law and would lift nearly 2 million children above the poverty line.[16] Helping families experiencing economic hardship to meet their basic needs would also expand long-term opportunities for children, such as by improving their educational outcomes. Research has found that giving low-income families additional income when a child is young not only tends to improve the child’s immediate well-being, but is associated with better health, higher educational performance, and higher earnings in adulthood.[17]

- EITC: Prior the Rescue Plan, nearly 6 million working adults not caring for children were taxed into, or deeper into, poverty because their EITCs were too small — or non-existent — to offset their payroll and income taxes. The Rescue Plan raised the maximum credit amount and phase-in rate to address this flaw.[18]

As the Securing a Strong Retirement Act of 2022 moves to the Senate and Congress considers various tax policy initiatives as potential parts of broader tax legislation, policymakers should keep in mind that for people with lower incomes, a fully refundable Child Tax Credit and expanded EITC for people without children at home are far more important than providing new tax advantages for retirement saving that would mostly help people with higher incomes.