- Home

- Federal Budget

- Will Congress Ease The Continuing Pressu...

Will Congress Ease the Continuing Pressure on Non-Defense Discretionary Programs or Worsen It?

As Congress finishes setting funding levels for annually appropriated programs for fiscal year 2017 and begins work on 2018 appropriations in the coming months, a key question is whether it will provide some relief from scheduled cuts, or will make the ongoing squeeze on these programs even more severe by enacting some or all of President Trump’s proposal for additional massive cuts in non-defense appropriations to offset his defense increase. The answer will determine whether the federal government finds it even more difficult to advance the wide range of priorities that are funded through non-defense appropriations, also known as non-defense discretionary programs.

This is the main budget area that invests in the nation’s future productivity, supporting education, basic research, job training, and infrastructure. It also supports priorities such as providing housing and child care assistance to low- and moderate-income families, protecting against infectious diseases, enforcing laws that protect workers and consumers, and caring for national parks and other public lands. A significant share of this funding comes in the form of grants to state and local governments.[1]

This is the seventh straight year of austerity in non-defense appropriations, driven by the multi-year appropriations caps of the 2011 Budget Control Act (BCA) and then further reduced by “sequestration” budget cuts.

- In 2017 the non-defense cap is frozen at the prior year’s level and in 2018 it falls by $3 billion, as the relief from sequestration that policymakers had previously enacted expires and the full sequestration cuts take effect for the first time.

- The 2018 cap is 16 percent below the comparable 2010 level when adjusted for inflation, and 21 percent below the 2010 level when adjusted for both inflation and population growth.

These figures, however striking, actually understate the likely cut to most programs. President Trump plans to greatly expand the number of immigration enforcement agents and build a border wall, and policymakers have already enacted $3 billion increases for veterans’ programs in both 2017 and 2018. In addition, policymakers would have to find additional funds to prepare for the 2020 census, as well as to avert problems such as cutting the number of low-income families receiving rental vouchers. To offset the cost of such measures, they would have to cut other non-defense appropriations even more.

[The cuts] would bring non-defense spending, as a share of gross domestic product, to a new record low.Nevertheless, the President would go further in cutting non-defense appropriations. As White House officials have announced, he plans to propose a $54 billion increase in defense for 2018 and pay for it by cutting non-defense appropriations. That would bring non-defense appropriations $54 billion below the existing cap in 2018 — that is, below the level with the full sequestration cuts. That would leave the non-defense total 11 percent below the 2017 level without adjusting for inflation and 25 percent below the 2010 level in inflation-adjusted dollars. If one takes into account the already enacted veterans’ increases and then assumes that policymakers do not cut homeland security programs, the inflation-adjusted cut in other areas since 2010 climbs to 32 percent. All of that would bring non-defense spending, as a share of gross domestic product (GDP), to a new record low.

Separate and apart from the President’s additional $54 billion cut in non-defense appropriations, however, just allowing the full sequestration cuts to take effect in 2018 would force cuts in key domestic areas and make it very difficult for policymakers to address significant funding shortfalls for needs such as job training to upgrade workers’ skills to fill in-demand jobs, child care assistance for working families (which currently helps only one in six eligible households due to funding limitations), treatment and prevention for addiction to opioids and other dangerous drugs, and maintenance backlogs at national parks and tribal schools.

Policymakers can alleviate the squeeze in 2018 and beyond by reducing the sequestration cuts in those years and substituting alternate deficit-reduction measures — as they have done on a bipartisan basis for each year from 2013 through 2017. (For more on the 2018 appropriations process, see box.) Those previous measures incorporated the principle of parity between defense and non-defense, dividing sequestration relief equally between those two categories in recognition that sequestration has created significant problems in both areas.

Seven Years of Austerity Have Squeezed Non-Defense Programs

The tight caps on defense and non-defense funding enacted in the BCA and reduced by sequestration continue to constrain appropriations (see the Appendix for further information on non-defense appropriations and their uses, the BCA caps, and sequestration).

Since 2012, policymakers have enacted, with bipartisan support, measures to reduce the sequestration cuts one or two years at a time. Like sequestration itself, the relief has always been equally divided between defense and non-defense. The most recent measure expires at the end of 2017; sequestration is scheduled to take full effect for the first time in 2018 and continue through 2021. For 2017, the cap on non-defense appropriations is $518.5 billion, essentially the same as the 2016 cap. For 2018, the cap is scheduled to fall by about $2.9 billion, to $515.7 billion.[2]

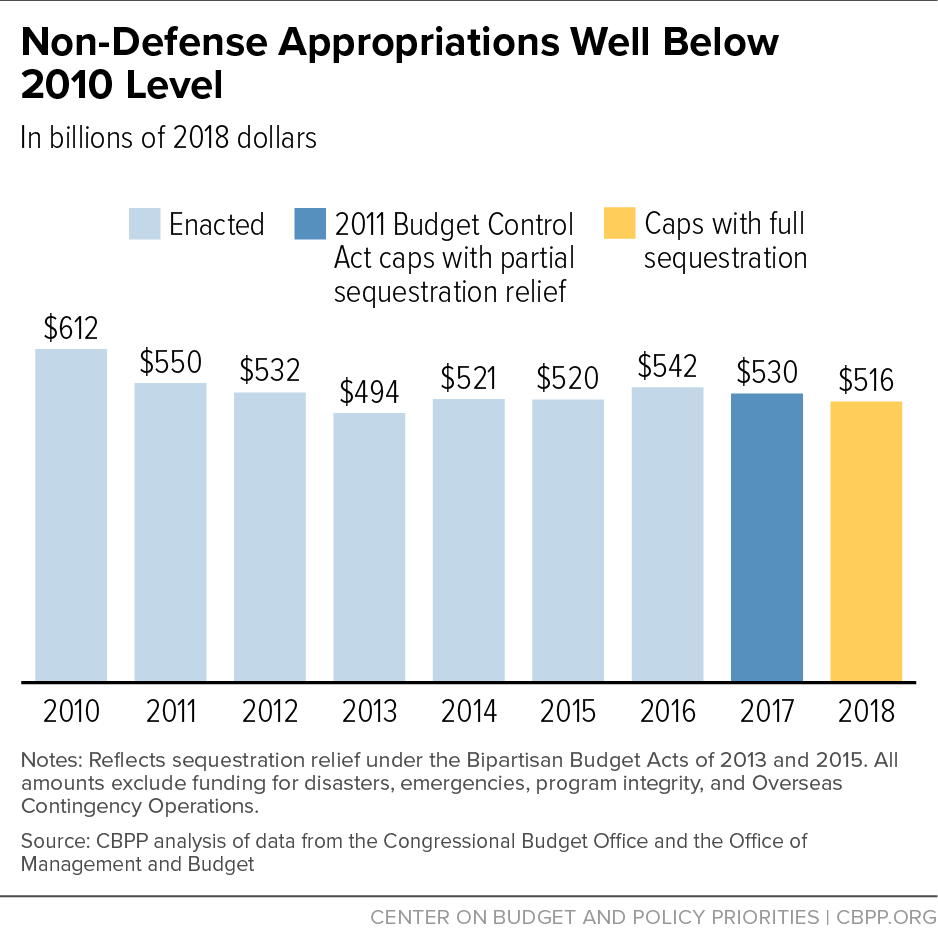

The 2017 freeze and 2018 cut are the seventh and eighth years of austerity in non-defense appropriations (see Figure 1, which shows the cap levels in inflation-adjusted dollars). While there have been ups and downs over the period, the cumulative downward effect is substantial. The 2018 non-defense cap is:

- $17 billion below the comparable 2010 level even before adjusting for inflation;[3]

- 16 percent below the comparable 2010 level after adjusting for inflation;[4] and

- 21 percent below the comparable 2010 level after adjusting for overall population growth as well as inflation.

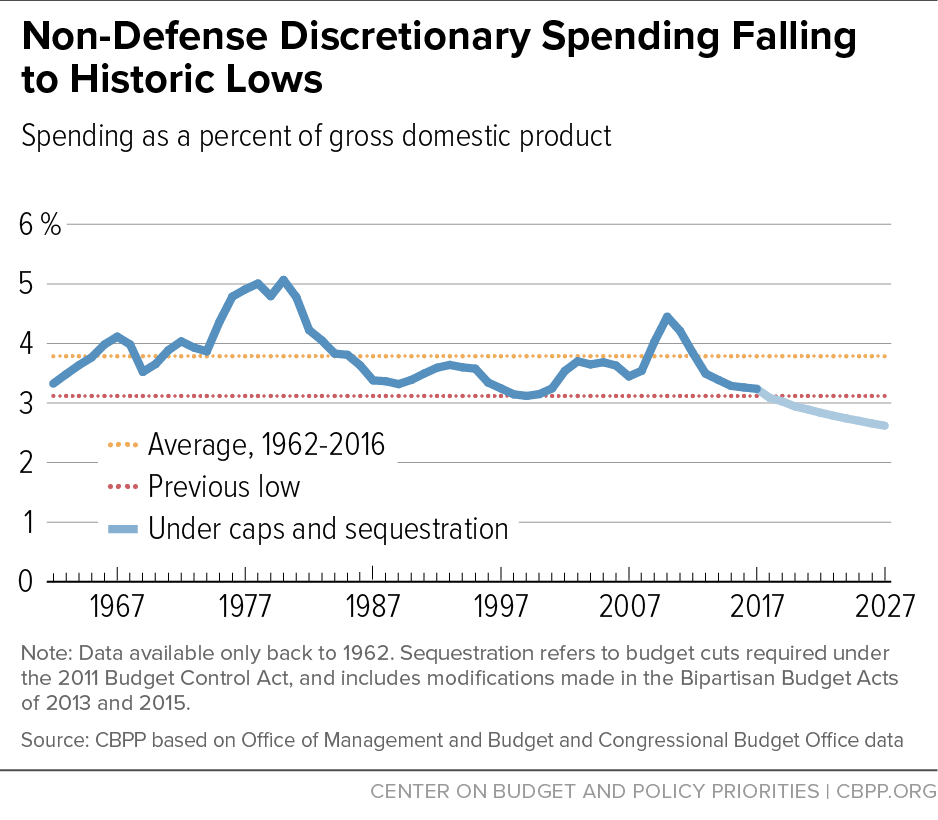

The decline is even sharper when measured relative to GDP — a standard way of comparing spending over long periods. On this basis, outlays for non-defense discretionary programs have been shrinking steadily since 2010. Under the caps and sequestration now in place, outlays for these programs in 2017 will equal 3.2 percent of GDP, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) projects — just 0.1 percentage point above the lowest percentage on record in data back to 1962. That percentage will continue to fall if the caps and sequestration remain unchanged, equaling the previous record low of 3.1 percent in 2018 and then continuing to fall (see Figure 2).

Further Pressures on Non-Defense Appropriations

The non-defense caps are even tighter than the overall numbers suggest. On top of general cost pressures felt throughout the government after seven years of appropriations austerity, various agencies and programs face additional cost pressures from factors such as the aging of the population and rising health care costs. But under the flat cap for 2017 and the decreasing cap for 2018, any increases to accommodate such needs will require offsetting cuts to other programs.

Veterans’ medical care. The Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) accounts for one-seventh of non-defense appropriations — mostly for medical services for veterans, where funding needs are growing due to rising health care costs, the needs of Iraq and Afghanistan veterans, and the aging of the veterans population.[5]

The enacted 2017 VA appropriations bill boosts funding by $2.9 billion (4.1 percent) and makes advance appropriations for 2018 for the main veterans’ medical care accounts, as is customary. Those 2018 appropriations provide, for the department, a $3.1 billion (4.2 percent) increase above 2017.

Census. In the Obama 2017 budget, the Census Bureau requested $778 million, a $182 million increase over the 2016 level, to stay on schedule with planning for the 2020 census. Projected funding needs for the census rise rapidly in later years, reaching roughly $2 billion in 2019 and $6 billion in 2020.[6] No accommodation within the caps has yet been made for these highly cyclical costs necessary to carry out a constitutionally mandated task. Funding constraints have already obliged the Census Bureau to cancel or postpone a number of field tests and other preparations for the 2020 census.

Housing assistance. Housing Choice Vouchers help more than 2 million low-income households — roughly half of which are seniors or people with disabilities (most of the rest are families with children) — afford to rent modest housing on the private market. With market rents rising at more than 3 percent per year on average (and with some additional vouchers having been issued in the past two years to reverse earlier cuts and assist homeless veterans), an increase of roughly $1 billion will likely be needed in 2017 just to continue assisting the current number of households.[7]

Social Security Administration (SSA). Rising workloads as the baby boom ages into its peak years for retirement and disability are compounding SSA’s general cost pressures due to inflation. SSA funding fell by 10 percent between 2010 and 2016, after adjusting for inflation. Over this period, SSA staff have shrunk by more than 5,000, field offices have closed, wait times have grown for assistance by phone and in offices, and the backlog of disability appeals awaiting a decision has reached record levels.[8]

Internal Revenue Service (IRS). IRS funding fell by 16 percent between 2010 and 2016, after adjusting for inflation.[9] As a result, fewer staff are available to answer the phones and audit returns, even though assisting in voluntary compliance and rooting out tax fraud produce a very high return on investment. Going forward, continued under-funding at IRS will result in greater tax noncompliance, worse service for taxpayers, and increased vulnerability to identity theft and cyberattacks.

In addition to these specific cost pressures, there is a strong case for doing more to meet important national needs in certain other areas. For example, only about one out of every six low-income working families eligible for child care now receive it, more job training slots are needed to help workers retool their skills for in-demand jobs, and funding is needed to allow Head Start centers to offer preschool programs that provide a full school-day and a full school-year of service. Other unmet needs range from treating and preventing substance abuse (including the opioid abuse epidemic) to reducing the maintenance backlog at national parks and tribal schools.

Finally, the Trump Administration says it intends to seek funding for a major expansion of immigration enforcement, including large increases in the number of immigration enforcement personnel and in detention capacity — costs that would normally all be charged against the non-defense appropriations caps. The cost of the proposed Mexican border wall could also come out of the caps.

Finishing 2017 Appropriations

The first step in this year’s appropriations process is to finish work on funding for fiscal year 2017, which began last October. Of the 12 annual appropriations bills, only the bill covering the Department of Veterans Affairs and military construction has been enacted. The remaining agencies and programs are operating under a continuing resolution (CR), which runs until April 28 (or sooner, if Congress completes regular appropriations). Republican leaders will probably combine the 11 remaining appropriations bills into one omnibus package.

The 2017 appropriations bills will be tight for the reasons described above. The overall cap on non-defense appropriations is frozen at the 2016 level while the VA has already received a $2.9 billion increase, so all other non-defense appropriations will have to shrink by $2.9 billion. It will be difficult enough to accommodate increases for unavoidable costs or highest priority needs; for everything else, purchasing power will continue to erode, and further cuts may be needed.

In addition, the Trump Administration is expected to send Congress a supplemental budget request in mid-March for increased defense spending and, on the non-defense side, for expanded immigration enforcement and wall construction. If Republicans insist that this additional non-defense funding be subject to the non-defense cap rather than treated as emergency items, the appropriations situation will be tighter still.

2018 and Beyond: Relief Needed, But Risks of Further Reductions

The non-defense appropriations cap for 2018 will be about $3 billion below the cap for 2017 in unadjusted dollars. With advance appropriations already enacted providing a $3.1 billion increase for veterans’ medical care in 2018, everything else will have to decrease by $6 billion unless Congress raises the cap.

Within that reduced total, Congress will need to find room for increases that are largely unavoidable (such as preparing for the 2020 census) and other high-priority items. In addition, increases to offset rising costs in a wider range of programs are needed to maintain basic government services, particularly where 2017 funding has remained flat or declined as compared to recent years. And Congress might want to provide more funding within the caps for immigration enforcement, deportations, and perhaps a border wall.

The Appropriations Process for 2018

The Trump Administration is expected to submit its 2018 budget (including appropriations requests) in two stages: a brief summary or preview in mid-March, followed by a full budget in May.

If the standard process is followed, sometime in the spring Congress will consider a budget resolution for 2018 and subsequent years, setting out intended budget levels and numerical goals for spending and tax legislation. This resolution is an internal congressional plan that does not itself become law or change existing law.

The budget resolution could be a vehicle for debating appropriations policy, including the outlines of a plan for sequestration relief. However, the budget resolution itself cannot change the cap levels. While a budget resolution could call for holding appropriations below the applicable cap (with the reduced total enforced by congressional budget rules), it could not, by itself, raise either the defense or non-defense cap. Rather, any increase in the BCA caps requires enactment of a law.

In several recent years Congress has been unable to agree on a budget resolution. If that happens again, Congress would have to work out its plans for appropriations totals through informal means.

With or without final agreement on a budget resolution, Congress will begin action on 2018 appropriations at some point, perhaps in May or June. (The Congressional Budget Act allows the House to take up appropriations bills even without agreement on a budget resolution after May 15.) Action on those bills may provide the real test of the viability of whatever appropriations strategy the Republican leadership adopts, showing whether there is sufficient support to pass bills once the top-line totals are translated into specific funding levels for individual agencies and programs.

Movement on sequestration relief legislation can occur at any point in this process. The relief packages for 2014-2015 and 2016-2017 were not worked out and passed until December and October, respectively.

For all these reasons, legislation is needed to provide sequestration relief in 2018 and beyond by substituting alternate deficit-reduction measures. Such legislation should provide equal relief for defense and non-defense, just as past relief measures have done.

While there has been a bipartisan consensus since 2013 that sequestration cuts are too deep, the Trump Administration is instead readying a proposal for massive new cuts to non-defense appropriations. White House officials have announced that the President’s 2018 budget will raise defense appropriations $54 billion above the 2018 cap and offset this increase by cutting non-defense appropriations by $54 billion below the already low post-sequestration level.[10]

The proposal would reduce total non-defense appropriations for 2018 by 11 percent or $57 billion[11] below the 2017 level, before adjusting for inflation. Moreover, if Congress simply retains the enacted VA increase for 2018 and doesn’t cut the Department of Homeland Security (DHS), the cut in everything else would be 15 percent. And that estimate is quite conservative, in part because the Trump Administration has made clear it will be seeking large increases for the Department of Homeland Security and may well seek further increases in veterans’ health care.

Exactly what President Trump will propose to cut remains unknown. The President’s funding requests for individual program areas are unlikely to be released until later this spring.

The extreme cuts reportedly planned by the Trump Administration are encountering widespread opposition. But for the reasons given in this paper, just leaving the full sequestration cuts in place in 2018 would create real problems for the federal government’s ability to provide needed services and investments. Instead, lawmakers should do what they have done for each previous year that sequestration has been in effect: come together on a package of alternate deficit-reduction measures to provide relief from sequestration on both the defense and non-defense sides of the budget.

Appendix: Background on Non-Defense Appropriations and the Budget Control Act

About one-third of the federal budget is determined through the appropriations process each year. It is referred to as “discretionary” spending because the laws establishing the programs and agencies give Congress discretion to set funding levels through annual appropriations.[12]

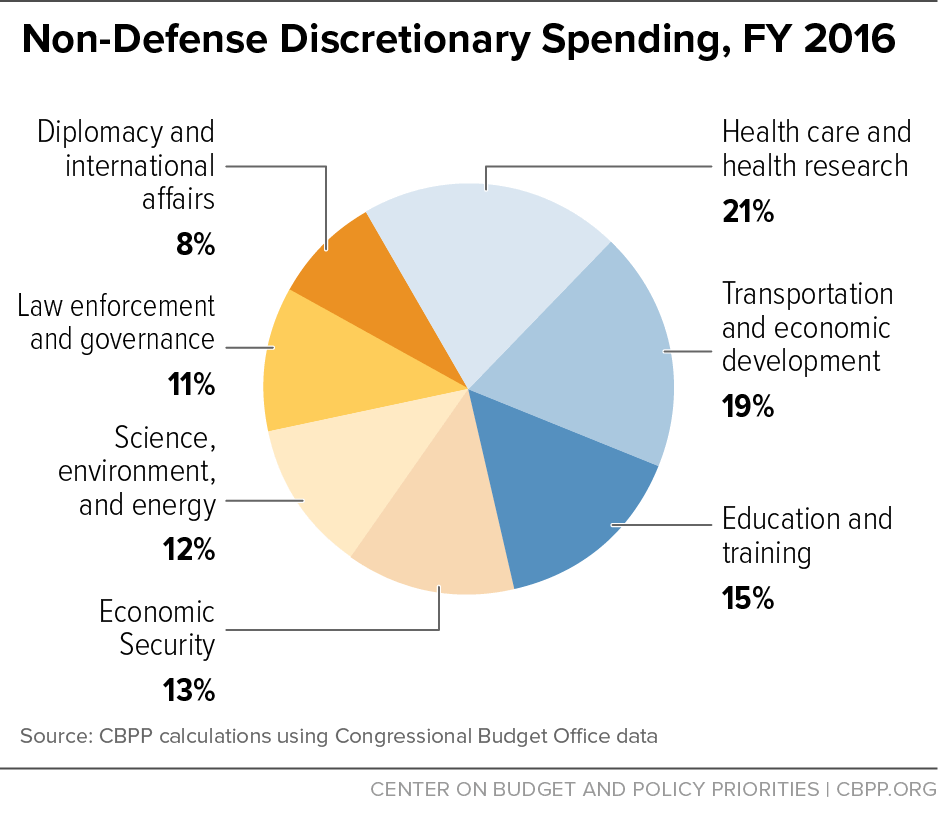

Of that amount, a bit more than half is for the Defense Department and closely related programs; the rest falls into the broad category of “non-defense discretionary” spending (often referred to as NDD). This category encompasses a wide range of activities, including, for example, law enforcement and courts, aid to education, scientific and medical research, veterans’ medical care, diplomatic activities and international assistance, housing programs, job training, public health, national parks and forests, some infrastructure, and the operating budgets of most federal agencies (see Figure 3). Nearly one-third of this spending reflects grants to state and local governments.[13]

Congress traditionally decides appropriations totals each year based on current assessments of needs and fiscal conditions. However, the 2011 Budget Control Act (BCA) established legally binding caps on appropriations for each year from 2012 through 2021, with separate caps for the defense and non-defense categories.[14] These caps effectively locked in the substantial cuts in non-defense appropriations enacted earlier in 2011 and used those as the starting point for further reductions.

The BCA also called for additional deficit-reduction measures and set up a process known as “sequestration” to automatically cut spending if other legislation were not enacted by the end of 2012 to meet a specified deficit-reduction target. No such legislation was enacted by the deadline, and the sequestration process was triggered, imposing equal cuts in defense and non-defense programs. For the first year, 2013, the law directed sequestration to be applied through across-the-board cuts to most appropriated programs. For subsequent years, however, it applies sequestration by reducing the caps below the levels set by the BCA.

Since 2011, policymakers have repeatedly enacted legislation to reduce — but not eliminate — the sequestration cuts, one or two years at a time, by substituting other deficit-reduction measures. In each case, sequestration relief was divided equally between defense and non-defense categories, just as the sequestration cuts themselves are divided. The most recent of these agreements covered 2016 and 2017. Without further legislation, full sequestration reductions to the caps will apply in 2018 and beyond.

Because of the pattern of sequestration relief, the non-defense cap for 2017 is essentially frozen at the 2016 level while the cap for 2018 actually falls by almost $3 billion. These cap levels are the net result of two opposite effects. The sequestration cut to the caps grows in 2017 and again in 2018, as the sequestration relief provided in 2015 legislation decreases in 2017 and ends entirely in 2018. At the same time, the pre-sequestration caps originally set by the BCA rise in both years, with the increase offsetting the additional sequestration fully in 2017 but only partly in 2018 (see Table 1).

| TABLE 1 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-Defense Appropriations, in billions of dollars | ||||

| 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | Change from 2017 to 2018 |

|

| Budget Control Act (BCA) caps | 530.0 | 541.0 | 553.0 | |

| Sequestration | -36.5 | -37.5 | -37.3 | |

| BCA caps after sequestration | 493.5 | 503.5 | 515.7 | +12.1 |

| Sequestration relief provided by BBA* | +25.0 | +15.0 | - | -15.0 |

| Final caps with sequestration relief | 518.5 | 518.5 | 515.7 | -2.9 |

* BBA = Bipartisan Budget Act of 2015.

Note: Details may not add to totals due to rounding.

Source: CBPP analysis of Office of Management and Budget and Congressional Budget Office data.

The BCA exempts certain appropriations from its caps. The largest exemption is for Overseas Contingency Operations (OCO), meaning funding that Congress and the President have designated as being for overseas military operations in conflict zones or for associated State Department and international assistance costs. Other exemptions are available for funding designated to meet emergency needs and for limited amounts of disaster assistance and funding to improve certain program integrity efforts.

In several recent years Congress has been unable to agree on a budget resolution. If that happens again, Congress would have to work out its plans for appropriations totals through informal means.

With or without final agreement on a budget resolution, Congress will begin action on 2018 appropriations at some point, perhaps in May or June. (The Congressional Budget Act allows the House to take up appropriations bills even without agreement on a budget resolution after May 15.) Action on those bills may provide the real test of the viability of whatever appropriations strategy the Republican leadership adopts, showing whether there is sufficient support to pass bills once the top-line totals are translated into specific funding levels for individual agencies and programs.

Movement on sequestration relief legislation could occur at any point in this process. The relief packages for 2014-2015 and 2016-2017 were not worked out and passed until December and October, respectively.

End Notes

[1]Iris J. Lav and Michael Leachman, “At Risk: Federal Grants to State and Local Governments,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, March 13, 2017, https://www.cbpp.org/research/state-budget-and-tax/at-risk-federal-grants-to-state-and-local-governments.

[2] The estimates of the 2018 cap are from the Congressional Budget Office; the final cap amount will eventually be calculated by the Office of Management and Budget and may be slightly different.

[3] We use the 2010 level as a point of comparison because it was the last year before cuts in non-defense appropriations occurred. Cuts in these programs were enacted in 2011 and then deepened starting in 2012 with the imposition of the Budget Control Act caps and sequestration. (See Appendix.) The 2010 appropriations included no Recovery Act funds, which were all provided in 2009.

[4] A relatively small part of these cumulative reductions reflects changes that don’t have a direct programmatic effect, such as increases in receipts from federal mortgage insurance, changes in certain mandatory programs (known as “CHIMPs”), and a decrease in Census Bureau funding after completion of the 2010 decennial census.

[5] While veterans’ compensation and pensions are mandatory programs, veterans’ medical care and the operating expenses of the Department of Veterans Affairs (including processing and evaluating claims for benefits) are funded through discretionary appropriations.

[6] U.S. Census Bureau Budget Presentation to Congress, Fiscal Year 2017 (February 2016), page CEN-11; http://www.osec.doc.gov/bmi/budget/FY17CBJ/Census%20FY%202017%20CBJ%20final%20not508.pdf.

[7] See Douglas Rice, “Substantial Funding Boost Needed to Renew Housing Vouchers in 2017,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, January 25, 2017, https://www.cbpp.org/research/housing/substantial-funding-boost-needed-to-renew-housing-vouchers-in-2017.

[8] See Kathleen Romig, “Cuts Weakening Social Security Administration Services,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, March 14, 2017, https://www.cbpp.org/research/social-security/cuts-weakening-social-security-administration-services.

[9] The inflation-adjusted cut is 18 percent if measured relative to the 2017 level in the continuing resolution. See Brandon DeBot, Emily Horton, and Chuck Marr, “Trump Budget May Slash IRS Funding Further Despite Mnuchin’s Call for More Resources,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, March 14, 2017, https://www.cbpp.org/research/federal-budget/trump-budget-may-slash-irs-funding-further-despite-mnuchins-call-for-more.

[10] Alex Guillen, Sarah Ferris, and Jeremy Herb, “White House Calls for $54B Bump in Defense Spending, Sharp Domestic Cuts,” Politico, February 27, 2017, http://www.politico.com/story/2017/02/trump-white-house-budget-blueprint-235435.

[11] The plan would reduce non-defense appropriations $54 billion below the 2018 cap, but since the 2018 cap is about $3 billion less than the 2017 level, the cut from 2017 is about $57 billion.

[12] The remainder is “mandatory” spending, which is determined by the rules for eligibility and benefits set in ongoing authorizing legislation. Examples include Social Security, Medicare, military and civilian retirement programs, Medicaid, SNAP (formerly known as food stamps), veterans’ compensation, and some farm programs.

[13] Lav and Leachman.

[14] Those categories have been in effect since 2014. For 2012 and 2013, there were instead caps on security and non-security appropriations, with security being a considerably broader category than defense.

More from the Authors