Substantial Funding Boost Needed to Renew Housing Vouchers in 2017

Freeze Would Leave Vouchers for More Than 100,000 Families Unfunded

End Notes

[1] For more on sequestration, see David Reich, “Sequestration and Its Impact on Non-Defense Appropriations,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, February 19, 2015, https://www.cbpp.org/research/federal-budget/sequestration-and-its-impact-on-non-defense-appropriations. For more on housing vouchers, see “Policy Basics: The Housing Choice Voucher Program,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, September 29, 2015, https://www.cbpp.org/research/housing/policy-basics-the-housing-choice-voucher-program.

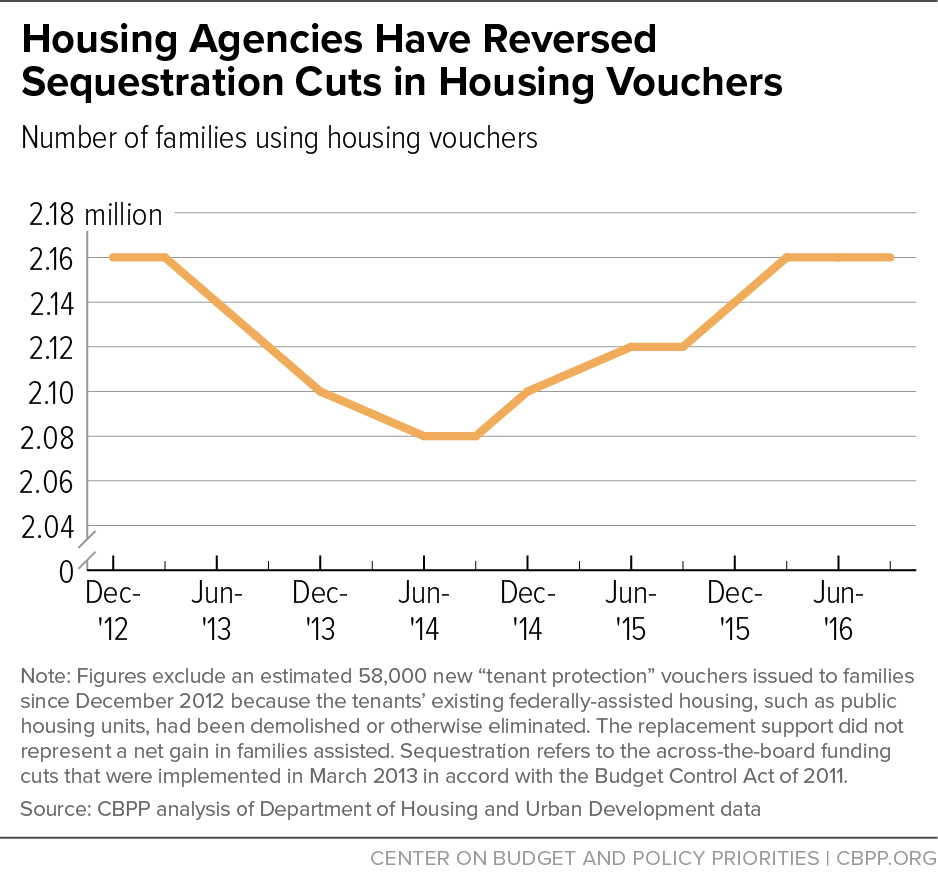

[2] This is a net figure: agencies cut the number of families using vouchers by more than 90,000, but these reductions were offset in part by the issuance of some 10,000 new vouchers for homeless veterans, funding for which was protected from sequestration. “Chart Book: Cuts in Federal Assistance Have Exacerbated Families’ Struggles to Afford Housing,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, April 12, 2016, https://www.cbpp.org/research/housing/chart-book-cuts-in-federal-assistance-have-exacerbated-families-struggles-to-afford.

[3] Agencies restored 58,000 vouchers from June 2014 to September 2016. This figure excludes new tenant protection and VASH vouchers leased during the period. A series of agreements to provide relief from the BCA’s sequestration-level spending caps enabled policymakers to increase funding for vouchers during these years.

[4] Joint Center for Housing Studies of Harvard University, America’s Rental Housing: Expanding Options for Diverse and Growing Demand, President and Fellows of Harvard College, 2015; and Alicia Mazzara, “Gap Between Rents and Renter Incomes Grew in 2015,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, November 1, 2016, https://www.cbpp.org/blog/gap-between-rents-and-renter-incomes-grew-in-2015.

[5] Barry L. Steffen et al., “Worst Case Housing Needs: 2015 Report to Congress,” Office of Policy Development and Research, U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, April 2015, https://www.huduser.gov/portal/publications/affhsg/wc_HsgNeeds15.html.

[6] National Center for Homeless Education, “Federal Data Summary, School Years 2011-12 to 2013-14,” UNC Greensboro, November 2015, http://nche.ed.gov/downloads/data-comp-1112-1314.pdf. These are the most recent data available.

[7] Will Fischer, “Research Shows Housing Vouchers Reduce Hardship and Provide Platform for Long-Term Gains Among Children,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, October 7, 2015, https://www.cbpp.org/research/housing/research-shows-housing-vouchers-reduce-hardship-and-provide-platform-for-long-term.

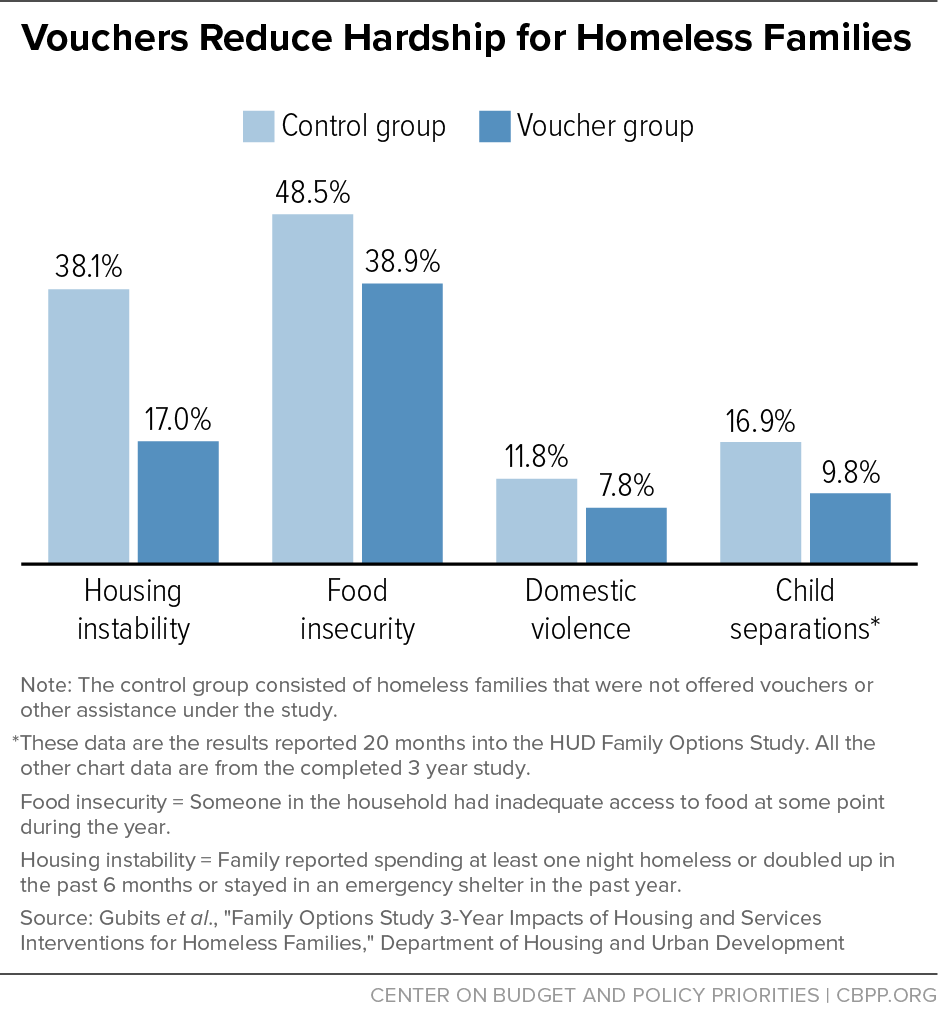

[8] Under the study, families living in homeless shelters were randomly assigned to receive one of three interventions — housing vouchers, rapid rehousing assistance, or transitional housing — or were assigned to a control group. See Daniel Gubits et al., “Family Options Study: 3-Year Impacts of Housing and Services Interventions for Homeless Families,” Department of Housing and Urban Development, October 2016, https://www.huduser.gov/portal/family_options_study.html. See also Ehren Dohler, “Major Study: Housing Vouchers Provide Haven for Homeless Families,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, November 4, 2016, https://www.cbpp.org/blog/major-study-housing-vouchers-provide-haven-for-homeless-families. The outcomes regarding family separations were identified 20 months after the beginning of the study, and detailed in the interim study report published in July 2015.

[9] Ehren Dohler et al., “Supportive Housing Helps Vulnerable People Live and Thrive in the Community,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, May 31, 2016, https://www.cbpp.org/research/housing/supportive-housing-helps-vulnerable-people-live-and-thrive-in-the-community.

[10] See the Home for Good Action Plan, http://homeforgoodla.org/actionplan.html, and “Federal sequester hits home for many of L.A.’s poor,” Los Angeles Daily News, March 21, 2016, http://www.dailynews.com/government-and-politics/20130321/federal-sequester-hits-home-for-many-of-las-poor.

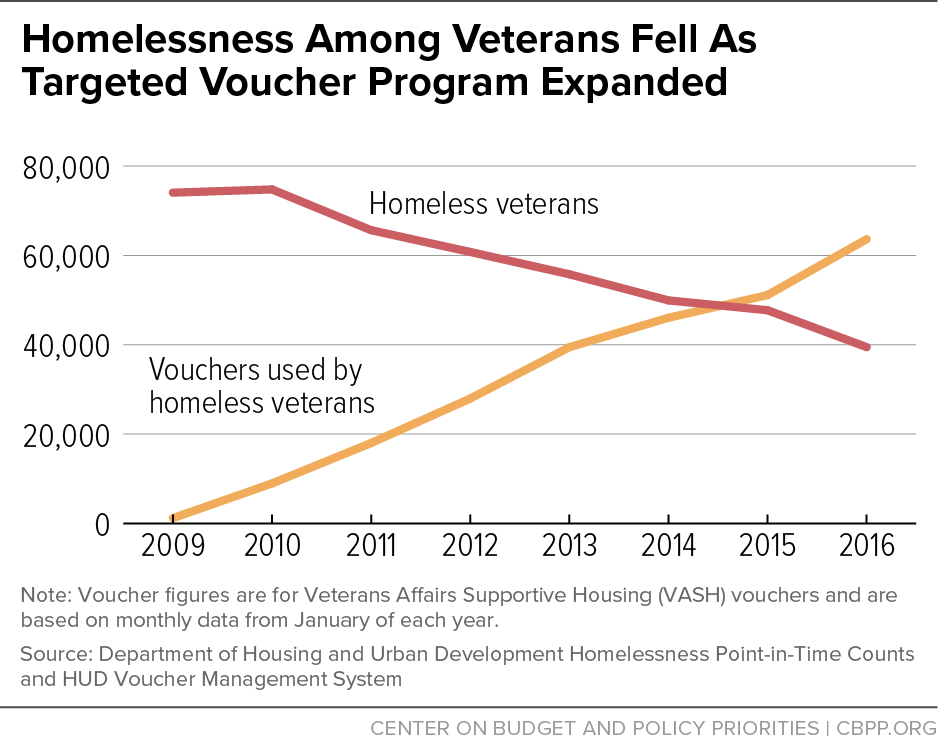

[11] Ehren Dohler, “Veterans’ Homelessness Cut in Half Since 2010,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, November 8, 2016, https://www.cbpp.org/blog/veterans-homelessness-cut-in-half-since-2010.

[12] Policymakers may be able to provide somewhat less than $18.86 billion in new funding if they tap federal reserves, as explained later.

[13] Source is CBPP analysis of HUD Voucher Management System data, except for the tenant protection voucher figure, which is a rough estimate based on annual allocations over the past several years. (HUD has not yet issued a notice of the tenant protection awards for fiscal year 2016.) Tenant protection vouchers are issued to replace assistance for households that were living in federally assisted public and private housing that has been demolished or otherwise removed from service.

[14] This figure represents a composite of the CPIs for residential rents, and fuels and utilities.

[15] Social Security Administration news release, https://www.ssa.gov/news/cola/. Roughly, the voucher subsidy equals the rent minus the tenant payment (which equals 30 percent of tenant income). For example, if the rent is $900 per month and the tenant’s income is $1,000 per month, then the tenant pays $300 (that is, 30 percent of income), and the voucher subsidy is $600 (= $900 - $300). If the rent increases 3.1 percent to $928, while the tenant’s income increases 0.3 percent to $1,003, then the voucher subsidy grows to $627 (= $928 - $301), an increase of 4.5 percent over the prior year subsidy of $600.

[16] For non-elderly, non-disabled households using vouchers, incomes rose 3.3 percent per year from 2012 to 2015, about the same as for American households in the bottom income quintile overall. CBPP’s estimate assumes that this trend will continue in 2017. Sources are CBPP analysis of HUD program data, and historical income tables available on the U.S. Census website, http://www.census.gov/data/tables/time-series/demo/income-poverty/historical-income-households.html.

[17] A composite of the CPI for residential rents and fuels/utilities for the first nine months of 2016 is 16.7 percent above the 2010 level, and will likely rise by roughly 3 additional percentage points in 2017, to nearly 20 percent above 2010. In comparison, voucher renewal funding eligibility of $18.86 billion in 2017 is 15.6 percent above the 2010 level.

[18] These figures assume that $280 million in excess reserves is available for a renewal funding offset in 2017. If no excess reserves are available, some 60,000 vouchers used by families would be left unfunded next year under the Senate bill, and 140,000 vouchers would be unfunded under a full-year continuing resolution.

[19] Agencies could attempt to mitigate cuts in the number of families assisted by failing to adjust voucher subsidies next year to keep pace with rising rents, thereby forcing many vulnerable voucher tenants to scrape together much higher rent payments. Following the 2013 sequestration cuts, however, housing agencies absorbed the lion’s share of the cuts by reducing the number of families using vouchers, even as some also took actions to impose sharp rent increases on voucher tenants. This experience suggests that efforts to increase tenants’ rent burdens would not significantly mitigate the loss of housing vouchers if policymakers fail to provide adequate renewal funding.