- Home

- Cuts In Federal Assistance Have Exacerba...

Chart Book: Cuts in Federal Assistance Have Exacerbated Families’ Struggles to Afford Housing

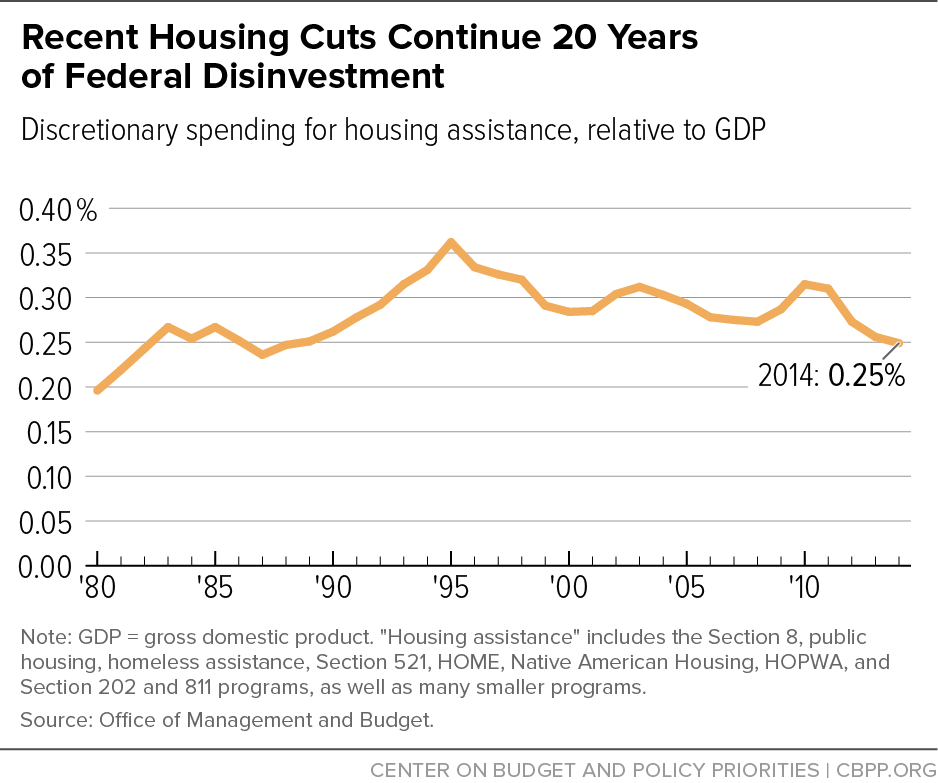

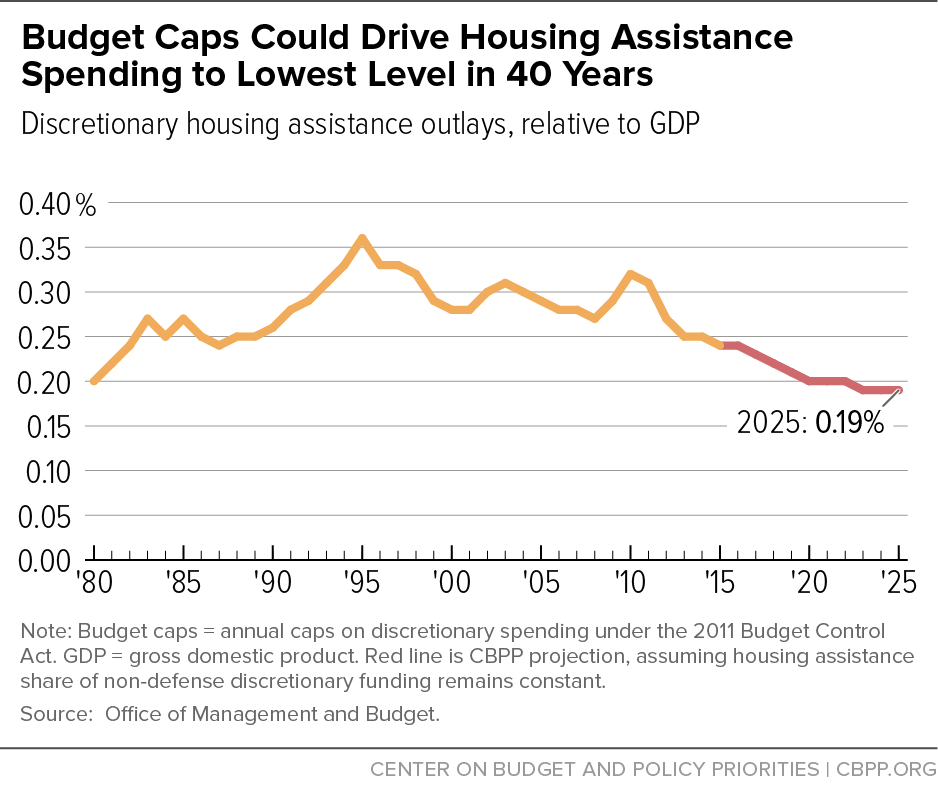

Increasing rents and stagnating wages have made it harder for families to keep a roof over their heads. Yet, funding for rental assistance has fallen sharply over the last six years, largely driven by rigid caps on non-defense discretionary programs that policymakers enacted as part of the Budget Control Act of 2011. Left unchanged, the budget caps could drive housing assistance spending to the lowest level since 1980, relative to the size of the economy.

These recent cuts have worsened a longer pattern of neglect by policymakers that’s increased hardship for low-income families and hampered local communities’ efforts to reduce homelessness.

Section 1: Six Years of Budget Austerity Have Weakened Housing Assistance Programs

Section 2: Budget Caps Have Worsened a Pattern of Neglect

Section 3: Rental Affordability Problems Have Worsened as Rental Assistance Expansion Has Slowed

Section 4: Housing Assistance Funding Could Fall to Lowest Level in 40 Years

Section 1: Six Years of Budget Austerity Have Weakened Housing Assistance Programs

Beginning in 2011, policymakers enacted a series of budget cuts that hit non-defense discretionary programs — the category that includes most housing assistance for low-income families — particularly hard. Most importantly, they approved the Budget Control Act of 2011 (BCA), which established tight budget caps through 2021 and mandated further reductions through a process known as sequestration.

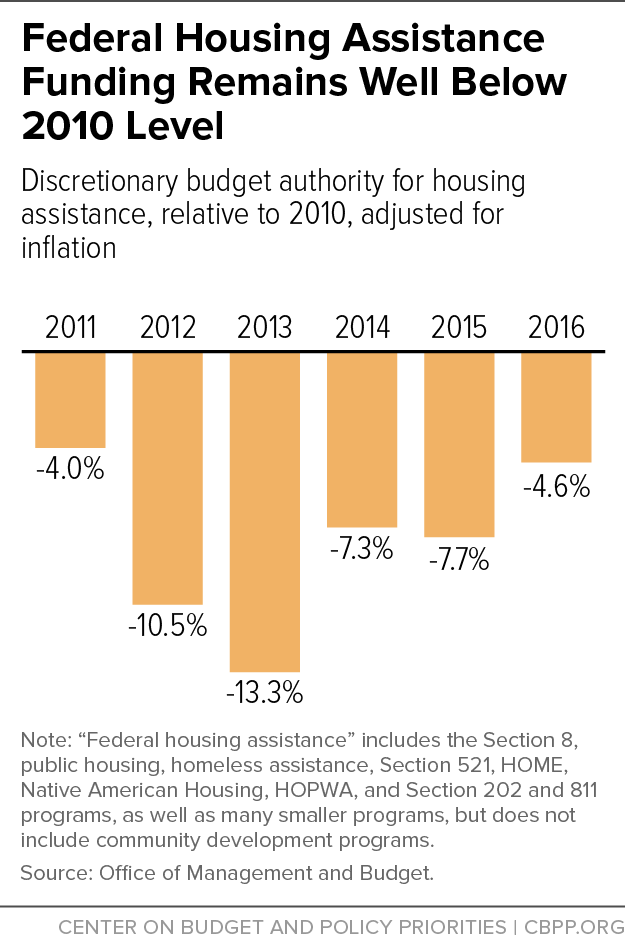

From 2010 to 2013, these actions caused annual housing assistance funding to fall by $6.2 billion, or 13.3 percent, in inflation-adjusted terms. Policymakers eased some of the sequestration cuts for 2014, 2015, and 2016, yet housing assistance funding in 2016 remains $2.1 billion, or 4.6 percent, below the 2010 level adjusted for inflation.

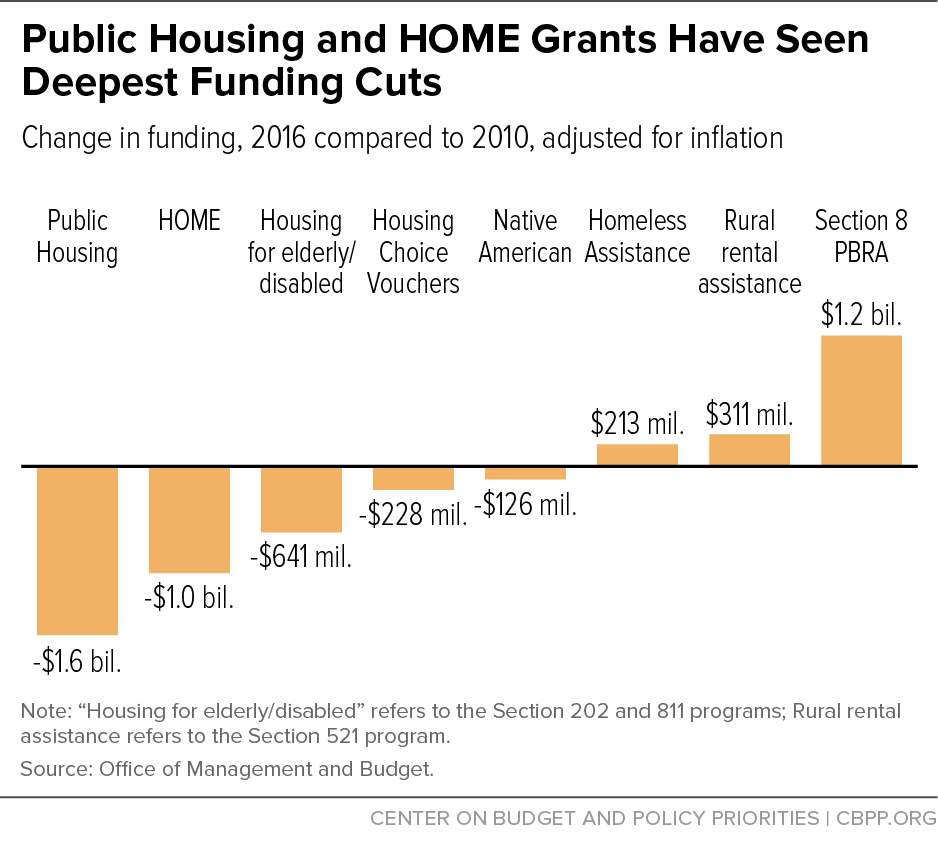

Public housing and the HOME block grant have suffered the deepest funding cuts. Public housing funding has fallen by $1.6 billion (21 percent) since 2010, while HOME funding has fallen by $1.0 billion (52 percent).

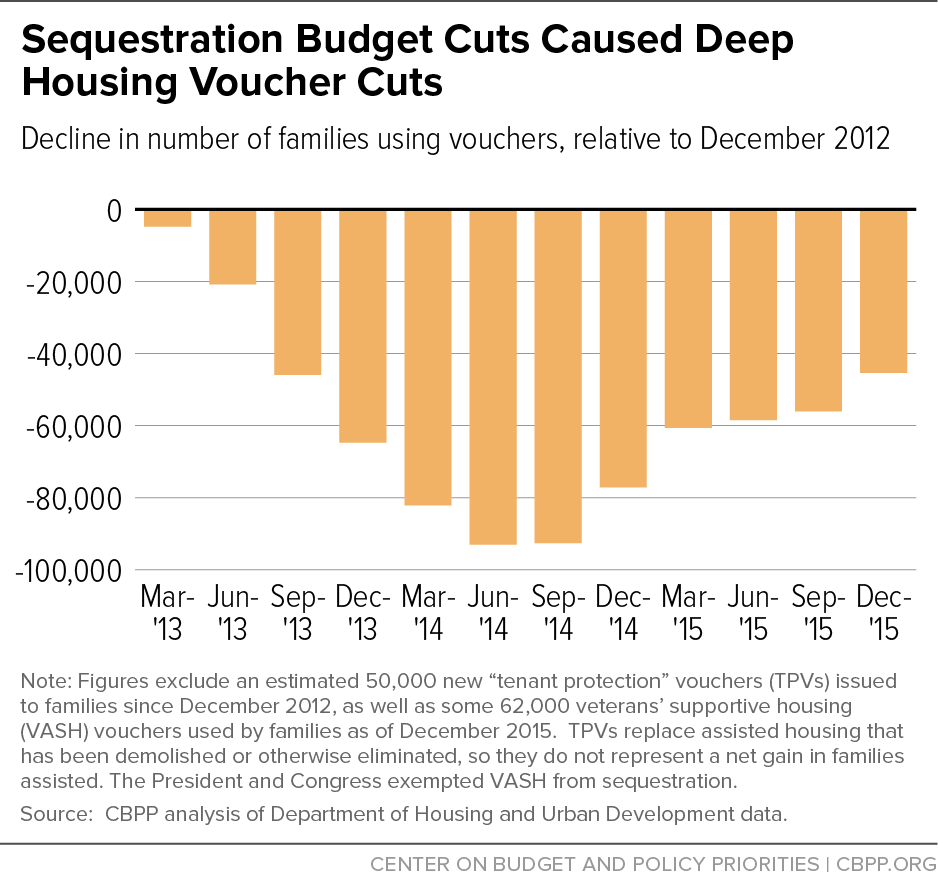

Cuts in Housing Choice Vouchers have had the largest and most immediate impact on low-income families. The number of families using housing vouchers fell sharply after the 2013 sequestration cuts. By June 2014, housing agencies were helping close to 100,000 fewer families due to sequestration. Agencies used the increased funds that lawmakers provided for 2014 and 2015 to restore about half of these vouchers by December 2015, but they were still serving some 45,000 fewer families than in December 2012.

Section 2: Budget Caps Have Worsened a Pattern of Neglect

The federal budget caps have worsened a pattern of neglect of low-income housing programs that began in the mid-1990s and contrasts sharply with the expansion and innovation that occurred over the several prior decades.

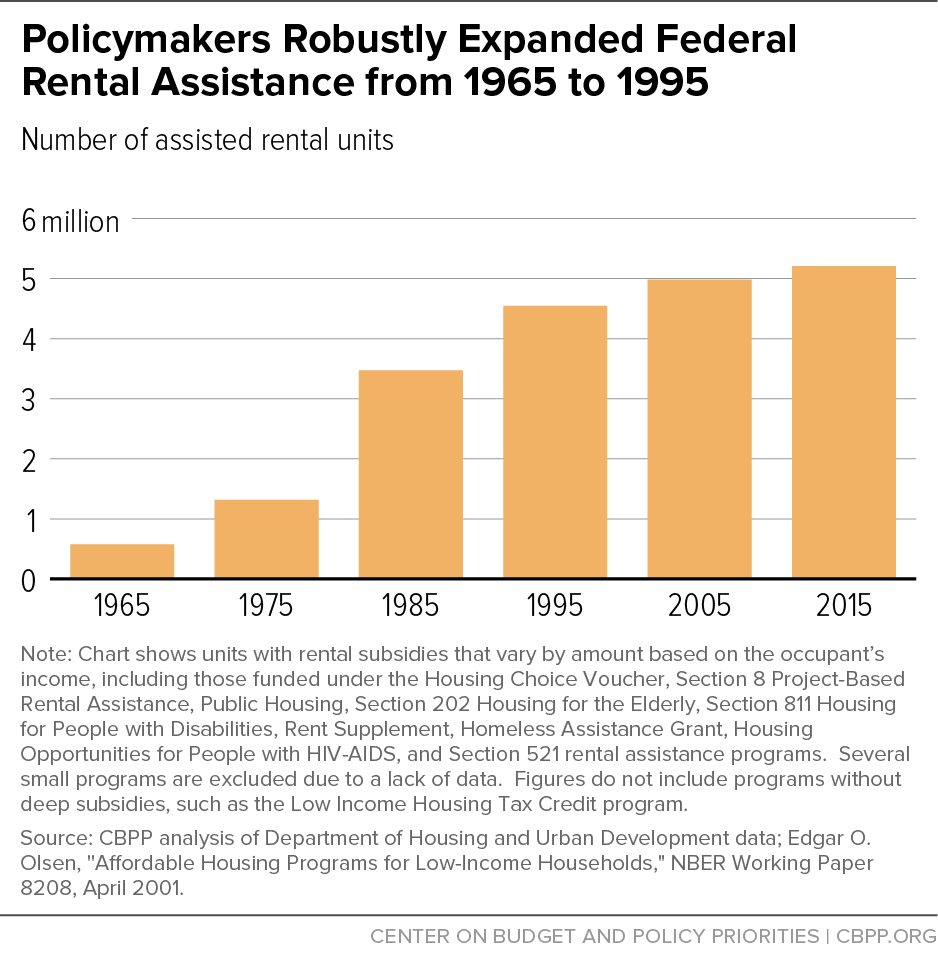

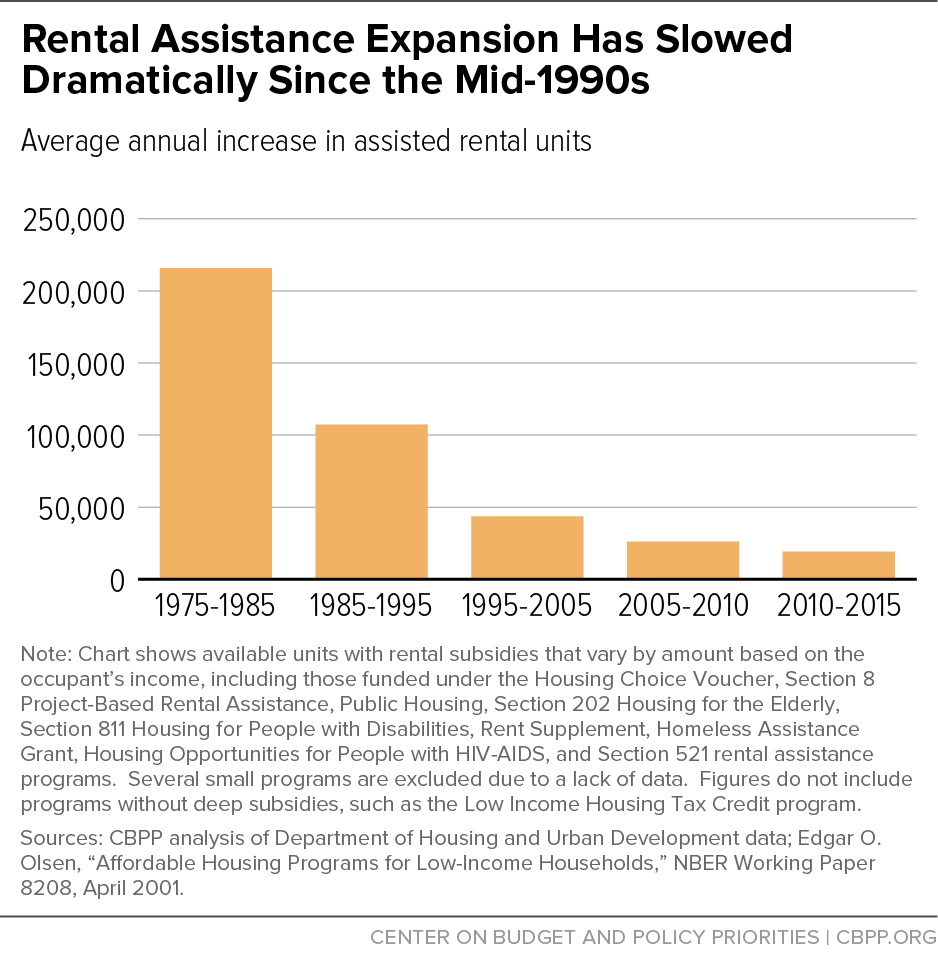

In the wake of the urban riots of the late 1960s, policymakers on both sides of the aisle began a sustained effort to expand affordable rental housing for low-income families. From 1965 to 1995, federal rental assistance available to low-income families grew from less than 600,000 to more than 4.5 million units. The Housing Choice (“Section 8”) Voucher and Section 8 Project-Based Rental Assistance programs, which lawmakers created in 1974 and expanded to serve nearly 3 million families by the mid-1990s, largely drove this growth.

This expansion of rental assistance was one of a series of efforts to strengthen the safety net that have collectively reduced poverty since the 1960s and currently cut poverty by roughly half.

Federal housing policy took a sharp turn, however, in 1996. While federal spending on housing assistance grew robustly, relative to gross domestic product (or GDP, a measure of the size of the economy), before then, it has fallen by 30 percent since.

Since the mid-1990s, federal rental assistance has helped a shrinking number of additional families — just an average of 20,000 additional families per year from 2010-2015. This is a sharp contrast from the average of 160,000 additional families helped each year from 1975 to 1995.

Policymakers have established several important initiatives to boost rental assistance since the mid-1990s, including funding nearly 60,000 new units of supportive housing for chronically homeless individuals since 2001, and more than 100,000 new housing vouchers for special groups, mostly homeless veterans, since 2008. These efforts have helped reduce veterans’ and chronic homelessness by significant margins. Nevertheless, these expansions have been modest compared to earlier efforts, and they have been offset in part by other cuts in rental assistance.

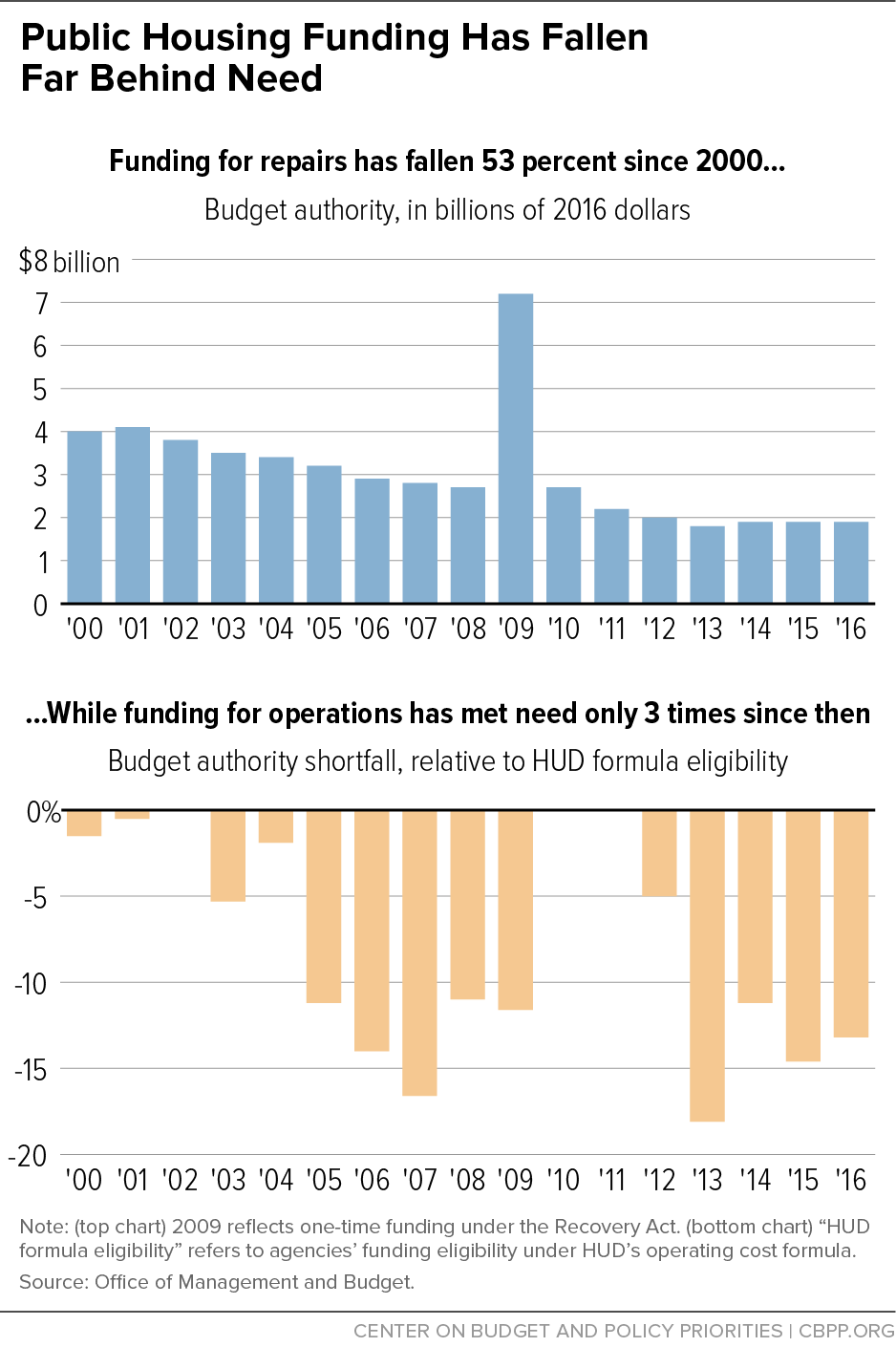

Policymakers have also failed to make the investments required to preserve the existing 1.1 million units of public housing. Public housing relies primarily on two funding streams: the Public Housing Capital Fund, which agencies use to repair and renovate public housing developments; and the Operating Fund, which covers operations costs such as verifying residents’ income and eligibility, maintaining units and preparing them for occupancy, and providing building security and other services.

Funding for both streams has been inadequate. Lawmakers have provided sufficient operations funding in just three years since 2000, while capital funding has declined 53 percent in that time, in inflation-adjusted terms, to just $1.9 billion in 2016, a level far below the amount that agencies need simply to cover new repair needs that accrue each year. As a result, the backlog of needed repairs — which HUD estimated in 2010 to be some $26 billion — continues to grow.

This chronic underfunding has made it increasingly difficult for agencies to maintain public housing developments. When developments deteriorate to the point at which they become uninhabitable or too costly to renovate, agencies must demolish or sell them. On average, this leads to the loss of about 10,000 units of public housing each year.

Section 3: Rental Affordability Problems Have Worsened as Rental Assistance Expansion Has Slowed

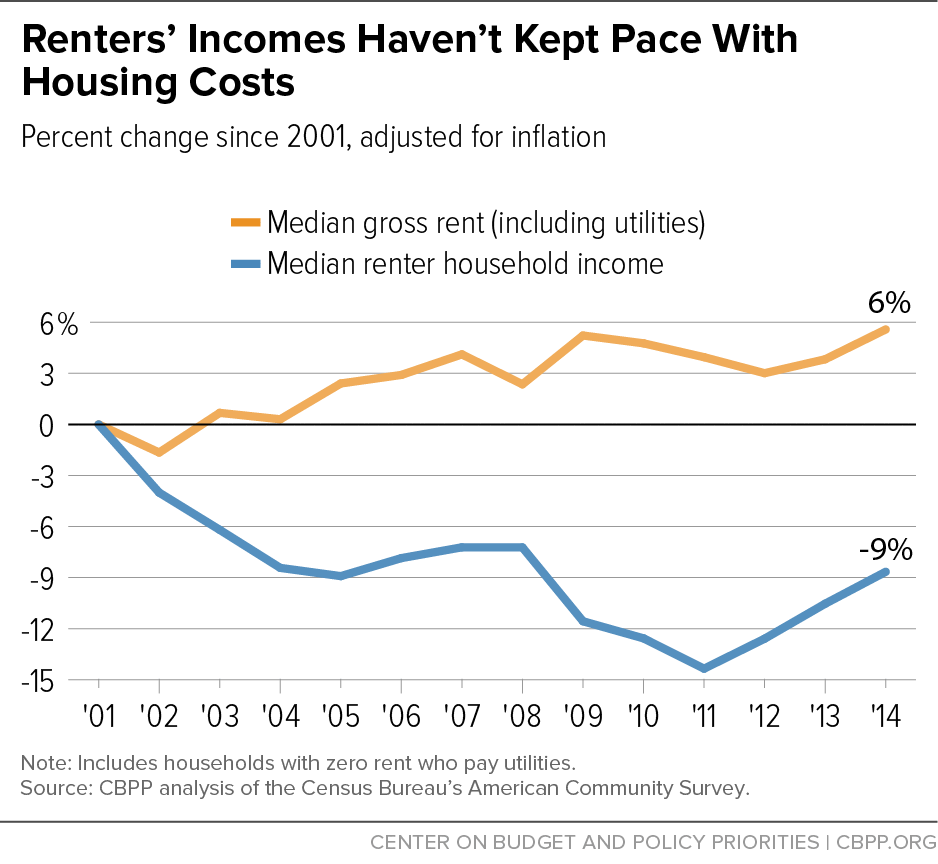

As policymakers have slowed the expansion of rental assistance to a trickle, the growth in the number of renters struggling to afford housing has far outpaced it. Renter incomes fell during the economic recessions that began in 2001 and 2007; as of 2014, they remained well below the 2001 level. At the same time, rental costs have continued to rise as the supply of rental units has failed to keep pace with a record-setting surge in the number of renter households.

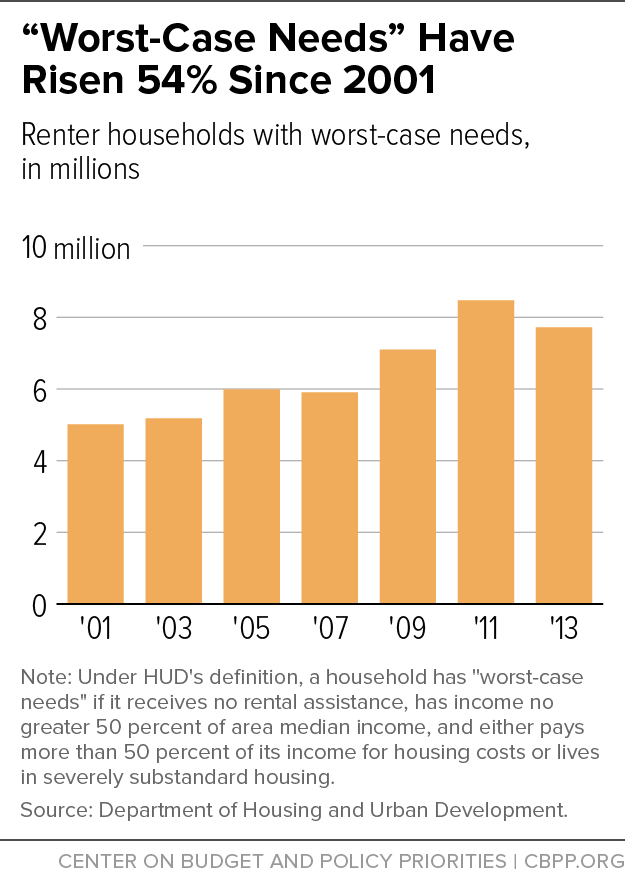

The growing gap between rents and incomes has particularly squeezed low-income families. From 2001 to 2013, the number of unassisted renter households with very low incomes (incomes no greater than 50 percent of the area median income) that are either paying more than half their income for rental costs or live in severely substandard housing — known as those with “worst-case needs” — increased 54 percent, from 5 million households in 2001 to 7.7 million households in 2013. Families with children have experienced the largest growth in worst-case needs.

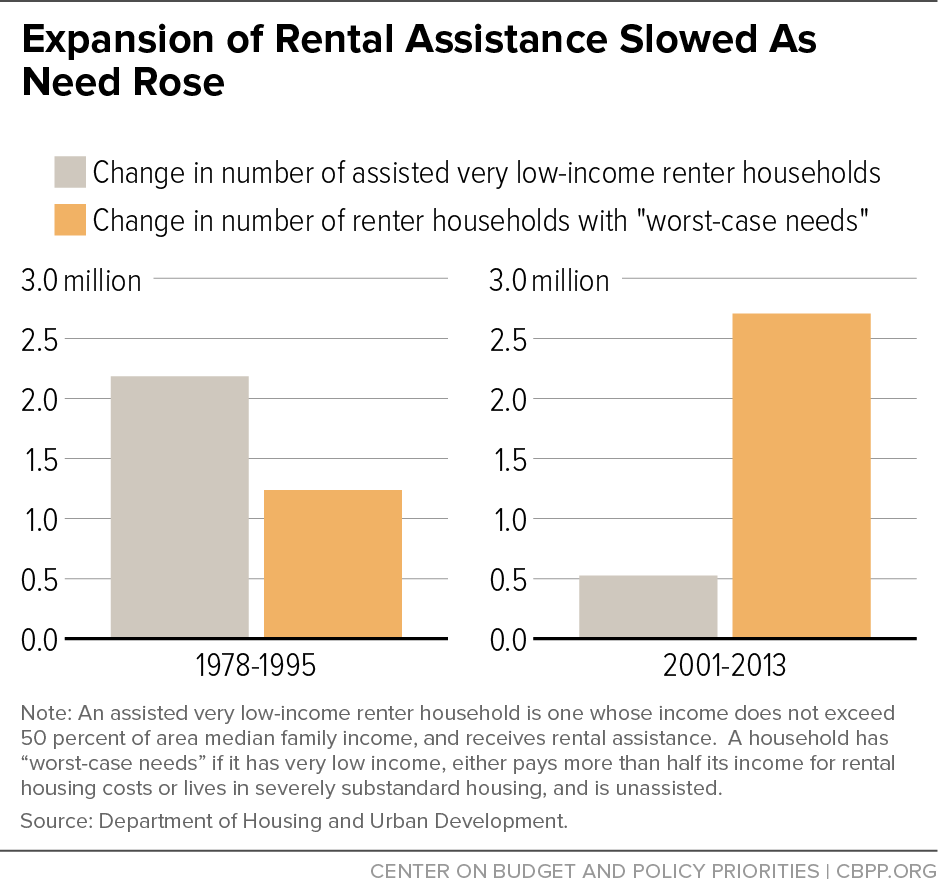

Over this same period, the number of very low-income households that received rental assistance rose by only 525,000. This weak response contrasts sharply with policymakers’ earlier successful efforts to address growing needs. As the number of very low-income renter households grew by 3.9 million from 1978 to 1995, policymakers expanded rental assistance to more than half this number of very low-income households. As a result, the increase in the number of renters with “worst-case needs” from 1978 to 1995 was about 1.4 million households — only half the size of the recent increase.

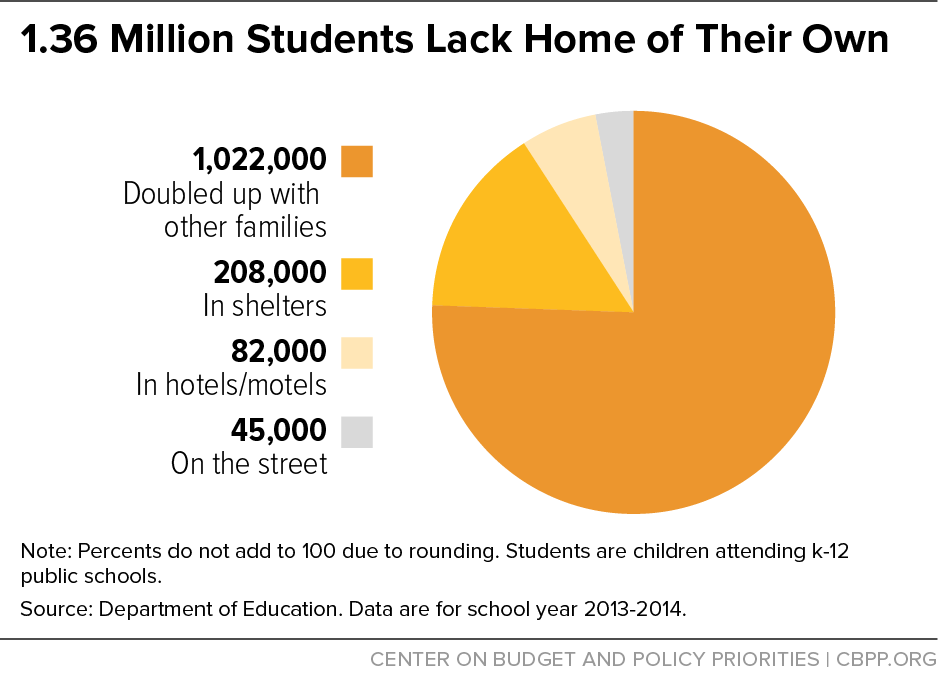

The impact of the growing gap between the incomes of low-income renters and the cost of rental housing also is evident in the large and persistent problem of housing instability and homelessness for families with children. Some 1.36 million school-aged children — an all-time high — lacked a home of their own in the 2013-2014 school year, Education Department data show. Numerous studies link homelessness to mental health and physical health problems, as well as poor school performance.

Section 4: Housing Assistance Funding Could Fall to Lowest Level in 40 Years

Federal budget caps created under the BCA have already caused deep cuts in housing assistance funding and could force even deeper cuts in coming years. If the caps are left unchanged and if housing assistance programs’ share of total non-defense discretionary funding does not increase, funding for housing assistance will soon fall to its lowest level in 40 years, relative to GDP.

Under the BCA caps, total non-defense discretionary program funding will increase at an average nominal rate of slightly more than 1 percent per year over the next five years. Meanwhile, the cost of renewing current federal rental assistance — which makes up roughly four-fifths of HUD’s budget and is driven largely by changes in private market rents — is likely to grow significantly faster as rent increases continue to outpace tenant income gains. And there are sound reasons to believe that growth in renter households will remain strong in coming years, continuing to increase rental costs.

Policymakers will be faced with a stark choice: reduce the amount of rental assistance available to low-income families, or sustain assistance for these families while deepening cuts in other non-defense discretionary programs, potentially including other housing and community development programs that HUD administers. Any efforts beyond sustaining the status quo — such as expanding rental assistance programs to achieve federal goals of eliminating homelessness, for example — would require even deeper cuts in other areas.

To avoid these choices policymakers must raise the BCA caps and expand rental assistance for low-income families. In addition to increasing funding for housing vouchers and other current programs, policymakers should explore innovative approaches to assisting families via tax credits and other avenues outside the discretionary budget.

More from the Authors