- Home

- Federal Budget

- Five Things To Look For In The President...

Five Things to Look for in the President's New Budget

President Trump's fiscal year 2019 budget will be the first articulation of his budget priorities since enactment of the new tax law.President Trump’s budget for fiscal year 2019, scheduled for release on February 12, will provide a detailed guide to the budget, tax, and program changes he seeks to achieve. It will be the first articulation of his budget priorities since enactment of the new tax law, which bestows large benefits on the wealthiest households and most profitable corporations and significantly increases deficits.

While the budget won’t reflect this week’s congressional budget agreement raising funding for defense and non-defense discretionary (annually appropriated) programs, it remains important, for two main reasons. First, it presents not only the President’s proposed funding levels for individual discretionary programs but also his broader fiscal agenda, including how he wants to change major entitlement programs — from health care to student loans to basic assistance for struggling families — as well as tax policy. Congress may consider some of these proposals later this year. Second, the budget outlines policies that the President will push for throughout his term, not just this year.

Unless the priorities in the new budget represent a sharp departure from last year’s Trump budget (and prior congressional Republican budget plans), it will present an agenda that would increase poverty, inequality, and the ranks of the uninsured while underfunding core public services and investments in various areas important for long-term growth.

The following are five questions to ask in evaluating the forthcoming Trump budget:

- Will it, like the Trump 2018 budget, call for repealing the Affordable Care Act (ACA) and cutting Medicaid deeply, causing millions of people to lose health coverage? Congress spent much of last year debating bills consistent with last year’s budget proposals.

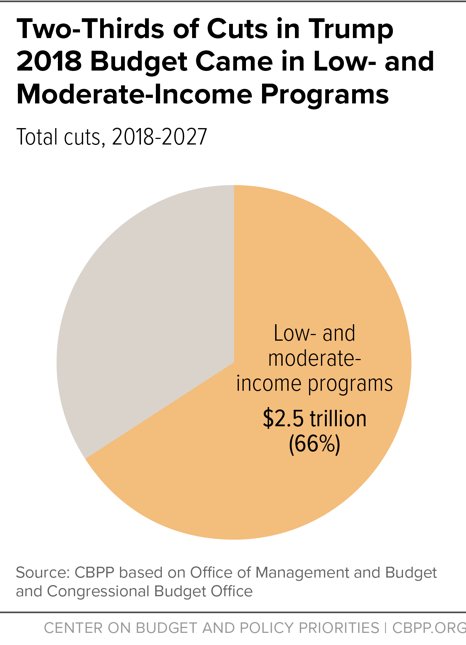

- Will it, like the Trump 2018 budget, call for deep cuts in nutrition, housing, and other basic assistance for struggling families, though the ink is barely dry on the new tax bill conferring large tax breaks on the wealthiest Americans? Two-thirds of the nearly $4 trillion in cuts in last year’s Trump budget would have come from taking various types of assistance and health care away from low- and moderate-income families and cutting various programs that promote opportunity, such as job training.

- Will the budget pair a high-profile new infrastructure initiative with cuts in other important infrastructure investments? The President is touting his infrastructure plan, but big questions about the plan remain unanswered. Last year’s Trump budget paired a modest new investment in infrastructure in the short term with reductions in highway funding, mass transit, and other transportation programs — resulting in cuts over the long term and likely shifting resources away from some of the most-needed infrastructure projects.

- Will it, like the Trump 2018 budget, call for deep cuts in non-defense discretionary funding over the next decade? The Trump 2019 budget almost certainly will have lower overall funding for non-defense discretionary programs in 2019 than in the new congressional agreement. That said, it will be important to consider the President’s proposed funding levels after 2019 and to evaluate whether they reflect serious proposals or are merely a gimmick to mask deficit levels under the budget.

- Will the budget use rosy, unrealistic economic assumptions and other gimmicks to mask the budgetary impact of the new tax law and gloss over the nation’s fiscal challenges? The Trump 2018 budget included only vague principles about tax reform, even as it claimed that its unspecified tax plan would both have no budgetary cost and help generate powerful “economic feedback” that, in turn, would add substantial revenue and reduce deficits by $2.1 trillion. This assumed “feedback effect,” coupled with deep budget cuts, enabled last year’s Trump budget to claim it reached balance within the decade. The tax plan that’s now been enacted will cost nearly $1.5 trillion over ten years and generate only enough added economic growth over the decade to reduce that cost by $385 billion, according to Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT) estimates. Moreover, if the law’s temporary tax provisions are extended — as the Administration apparently favors — the cost of the tax bill will climb even higher.

Health Care

Last year’s Trump budget would have cut $1.9 trillion from health care programs by repealing the ACA and imposing a “per capita cap” on federal Medicaid funding, which would limit per-person federal Medicaid expenditures irrespective of need. While the budget provided little detail, congressional Republicans spent much of the year debating ACA “repeal and replace” bills consistent with the budget’s broad outlines.

Those bills would have caused more than 20 million people to lose health coverage, shrunk subsidies for low- and moderate-income marketplace consumers, weakened protections for people with pre-existing conditions, and ended the ACA’s Medicaid expansion for low-income adults. The bills also would have imposed a per capita cap on Medicaid funding for families with children, seniors, and people with disabilities.

Congress didn’t pass those bills. But the tax bill enacted in December repealed the ACA’s individual mandate, the requirement that most people have coverage or pay a penalty. Repeal of the mandate will increase individual insurance market premiums, create additional uncertainty and confusion in the individual market, and cause millions of people to become uninsured. The Administration has also proposed regulatory changes that would lead to further increases in individual market premiums and coverage losses, and the Administration is encouraging states to make changes in Medicaid that would make it harder for many low-income adults to secure and retain Medicaid coverage.[1]

Despite these legislative and administrative actions, almost 12 million people signed up for coverage in the ACA marketplaces during this year’s open enrollment season. Another 12 million people are covered due to the Medicaid expansion, and another 64 million are covered under the pre-ACA Medicaid program. Millions more, including many people with job-based health plans, have better coverage because of the ACA — for example, plans without annual or lifetime limits.

One key question is whether this year’s Trump budget will set aside efforts to repeal the ACA and radically restructure and cut Medicaid. Congress seems unlikely to attempt comprehensive ACA repeal or Medicaid restructuring this year. But if such proposals appear once again in the President’s budget, that will indicate he remains committed to pursuing them in the future if a political opportunity arises.

Programs for Families and Individuals with Limited Means

The Trump 2018 budget called for unprecedented cuts in programs that help low- and moderate-income families afford the basics — food, rent, and health care — and improve their prospects for upward mobility. Fully two-thirds of that budget’s nearly $4 trillion in cuts over ten years would have come from such programs.[2] (See Figure 1.)

In addition to the cuts in health care noted above, the Trump 2018 budget proposed to cut food assistance provided by the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP, formerly known as food stamps), income assistance for low-income families raising children with serious disabilities (such as Down syndrome, cerebral palsy, and autism), and the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) program, which provides funding to states for income assistance, employment programs, child care, and other supports for families with children. The 2018 budget also called for significant cuts in key discretionary programs that provide assistance and promote opportunity, including job training, rental assistance, and the Low Income Home Energy Assistance Program. As explained below, it called for even deeper cuts in overall non-defense discretionary funding after 2018.

Such cuts could be especially difficult to justify this year in the wake of a tax bill that bestows generous tax-cut benefits on those at the top of the economic ladder.

Last year, Administration officials defended many of their proposed cuts by suggesting that their policies would cause more people to find work — even though the vast majority of adult participants in these programs already work or are unable to work due to health issues or other factors, and even though the cuts would have hit low-income children, seniors, and people with disabilities. Last year’s budget would have cut or ended basic assistance for millions of struggling families and made it harder for such families to get back on their feet.

This year the White House again may seek to portray cuts in basic assistance programs as ways to improve employment prospects for people struggling in today’s economy. Remarks by the President and others suggest that the 2019 budget could propose denying health care and rental assistance[3] to people who aren’t working or participating in specified work activities, regardless of whether jobs or job training are available, and could seek to make existing work requirements in SNAP and TANF more restrictive. Two decades of real-world experience in TANF show that imposing inflexible work requirements is likely to cause many people to lose badly needed assistance, while failing to improve long-term employment and earnings. [4]

For example, rigid work requirements can harm working families whose work hours fluctuate and who thus sometimes fall below the required work-hours threshold because their employers didn’t schedule them for enough hours in a given month. And families often lose assistance due to difficulties in satisfying extensive paperwork requirements to document that they’re already working or qualify for an exemption because they are in ill health, are caring for a family member with a disability, or are struggling with a substance use disorder or domestic violence crisis.

To be sure, the President seemed to suggest in the State of the Union address that his budget may increase funding for job training and career and technical education — areas that his 2018 budget cut significantly. But if his new budget also calls for deep cuts in 2020 and beyond in non-defense discretionary funding and Congress goes along with those cuts, funding for job training would likely fall over the decade.

Infrastructure

Repeating a version of a promise he has made since the 2016 campaign, President Trump said in his State of the Union address that he soon would present a proposal to support $1.5 trillion in infrastructure spending over ten years. New details about the plan will be released with the budget, according to the Administration.[5]

The Administration says the core of its proposal will be approximately $200 billion in new federal resources that would “leverage” much larger amounts of state, local, and private resources and achieve a total of more than $1 trillion in infrastructure investment over the decade. A look at last year’s Trump budget suggests, however, that the new federal support might eventually be more than offset by other infrastructure cuts that the President may also propose. Last year’s budget proposed immediate cuts to discretionary funding for the Department of Transportation — including mass transit and Amtrak — and would also have cut key infrastructure programs in the Army Corps of Engineers, the Agriculture Department, and Department of Housing and Urban Development. And because overall funding for non-defense discretionary programs would have been cut severely after 2018, these infrastructure-related cuts would almost certainly have grown deeper over time.

The Trump 2018 budget also effectively imposed a major, permanent cut in the Highway Trust Fund — reaching $20 billion a year by 2027 and extending indefinitely — by proposing that the trust fund spend no more in a given year than the dedicated revenues it receives. In recent years, lawmakers have filled “gaps” in the trust fund with general revenues to avoid cutting resources for highways as gasoline tax revenues erode. But the Trump budget issued last year departed from that course.

By providing only a modest share of the funding needed for its proposed infrastructure investments, the President’s proposal also appears — based on leaked details — to rely on states, cities, and the private sector to cover the vast majority of the costs. But the Administration hasn’t explained where that money would come from. Most likely, the Administration’s approach would favor projects that can yield profits for private investors, meaning that many needed projects — in mass transit, school repairs, and the like — could get short shrift even as some private investors secured lucrative gains.

Non-Defense Discretionary Programs

Bipartisan congressional negotiators have reached an agreement to raise overall defense and non-defense discretionary funding for 2018 and 2019, above the tight caps imposed by the Budget Control Act of 2011 (BCA) and reduced further by the BCA’s “sequestration” process. Bipartisan agreements reached in December 2013 and November 2015 also raised funding above the sequestration levels for two years at a time, though this part of the budget still saw sizable cuts. Even with the new agreement, overall non-defense discretionary funding in 2018 still would be 5.3 percent below its 2010 level after adjusting for inflation — and well below its historical average (based on data back to 1962) when measured as a share of the economy.

While the bipartisan congressional budget agreement includes a higher level of non-defense discretionary funding for 2018 and 2019 than the President’s budget will likely recommend, the Appropriations Committees will at least consider the President’s spending priorities for individual programs. Last year’s budget not only failed to recognize the need for more adequate non-defense funding, but proposed to slash non-defense funding a stunning $54 billion below the sequestration level in 2018 alone, targeting cuts in a range of non-defense areas, including education, environmental protection, and housing assistance.

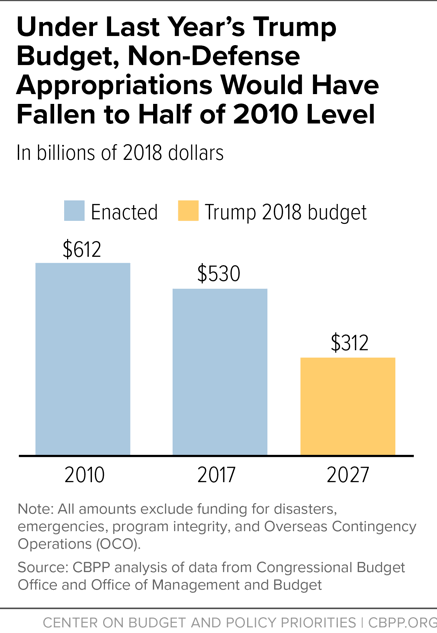

Further, last year’s Trump budget called for deeper cuts in total non-defense discretionary funding with each passing year, with the cut reaching 41 percent (in inflation-adjusted terms) by the tenth year.[6] (See Figure 2.) Cuts of this magnitude would require a drastic scaling back of government efforts in multiple areas, such as science, education, public health, environmental protection, the national parks, the courts, Social Security offices, and even infrastructure.

It remains to be seen whether the Trump 2019 budget will again propose to dramatically shrink funding for non-defense appropriations over the decade. Given the large unmet needs funded by this area of the budget,[7] such deep cuts may strike observers as highly implausible. But if they aren’t serious, then they’re a gimmick to artificially hold down the budget’s projected deficits.

The Budget’s Economic Assumptions

The Trump 2019 budget’s assumptions regarding matters such as economic growth and revenues over the coming decade will have a major impact on its forecast for deficits under the President’s policies. Last year’s Trump budget projected that the budget would reach balance in 2027 and that deficits in 2018-2027 would total $3.2 trillion under the President’s policies — or $5.6 trillion less than under existing policies. To get that much deficit reduction, the Administration relied heavily on unrealistic economic assumptions and other gimmicks, along with deep proposed cuts in numerous areas. The Congressional Budget Office’s (CBO) re-estimate of last year’s Trump budget, using CBO’s economic projections and technical estimating models, projected it would leave the country with $6.8 trillion in deficits over the decade. CBO attributed $3.2 trillion of the roughly $3.7 trillion difference between its estimates and the Administration’s to differences in economic assumptions.

For example, the Trump 2018 budget assumed that economic growth would average 2.8 percent annually over the decade, after adjusting for inflation, while CBO projected 1.7 percent. That’s an unprecedent gap between a President’s growth forecast and CBO’s.[8] The Administration argued that its tax, regulatory, and trade policies would generate much faster growth and higher revenues than CBO’s projections, but provided few details about the policies that supposedly would ignite this robust growth. Most analysts found these growth and revenue projections implausible.

Last year’s Trump budget preceded the drafting of the major tax law enacted in December. The budget provided principles for a tax reform plan but no details and assumed that the tax plan would be revenue neutral. But the tax plan enacted in December carries a projected cost of nearly $1.5 trillion over ten years, or about $1.1 trillion after the assumed impact on the economy is factored in, according to the official JCT estimate.

Moreover, to keep the plan’s official cost down, many of its individual tax cuts (though not its corporate tax cuts) are slated to expire after 2025. Yet the Administration has made clear that it supports making the tax cuts permanent — which would push the tax cuts’ cost closer to $2 trillion before any impacts on the economy are factored in.

Now that the tax law’s provisions are known and CBO and JCT have estimated their economic and budgetary effects, it will be instructive to see what revenue levels and economic growth rates the President assumes in his 2019 budget. If, as expected, the budget proposes no new revenue, it may once again rely on implausible assumptions of large “economic feedback” effects from its policies in order to show lower deficits.

CBO hasn’t released baseline economic and budget projections since last June and isn’t expected to release its analysis of the President’s new budget until March, so there won’t be recent CBO projections to provide a context for the economic and budgetary estimates that appear in the 2019 Trump budget. But while CBO may revise its economic growth projections upward for the next few years to reflect short-run stimulus from the tax cuts, any new claims in the forthcoming Trump budget of huge economic feedback from the new tax law — claims the budget may use to mask the tax law’s impact on the deficit — would not likely withstand scrutiny.

End Notes

[1] See Sarah Lueck, “Health Care Executive Order Would Destabilize Insurance Markets, Weaken Coverage,” CBPP, November 29, 2017, https://www.cbpp.org/research/health/health-care-executive-order-would-destabilize-insurance-markets-weaken-coverage, and Judith Solomon, “Kentucky Waiver Will Harm Medicaid Beneficiaries,” CBPP, January 16, 2018, https://www.cbpp.org/research/health/kentucky-waiver-will-harm-medicaid-beneficiaries.

[2] Isaac Shapiro, Richard Kogan, and Chloe Cho, “Trump Budget Gets Two-Thirds of Its Cuts From Programs for Low- and Moderate-Income People,” CBPP, September 29, 2018, https://www.cbpp.org/research/federal-budget/trump-budget-gets-two-thirds-of-its-cuts-from-programs-for-low-and-moderate.

[3] Will Fischer, “Trump Plan to Condition Rental Assistance on Work Will Hurt Families, Not Support Work,” CBPP, February 7, 2018, https://www.cbpp.org/blog/trump-plan-to-condition-rental-assistance-on-work-will-hurt-families-not-support-work.

[4] LaDonna Pavetti, “Work Requirements Don’t Cut Poverty, Evidence Shows,” CBPP, June 6, 2017, https://www.cbpp.org/research/poverty-and-inequality/work-requirements-dont-cut-poverty-evidence-shows.

[5] Jacob Leibenluft, “Three Key Questions about the Trump Infrastructure Plan,” CBPP, January 30, 2018, https://www.cbpp.org/research/federal-budget/three-key-questions-about-the-trump-infrastructure-plan.

[6] David Reich, “Trump Budget Would Cut Non-Defense Programs to Half their 2010 Level,” CBPP, May 23, 2017, https://www.cbpp.org/blog/trump-budget-would-cut-non-defense-programs-to-half-their-2010-level.

[7] David Reich and Chloe Cho, “Unmet Needs and the Squeeze on Appropriations,” CBPP, May 17, 2017, https://www.cbpp.org/research/federal-budget/unmet-needs-and-the-squeeze-on-appropriations.

[8] Chad Stone, “Gap Between Trump, CBO Predictions on Economic Growth the Largest on Record,” CBPP, May 22, 2017, https://www.cbpp.org/research/federal-budget/gap-between-trump-cbo-predictions-on-economic-growth-the-largest-on-record.

More from the Authors

Areas of Expertise

Recent Work:

Areas of Expertise