In July, the Council of Economic Advisers (CEA) released a report designed to buttress the Trump Administration’s case for proposals that take away basic food assistance, housing assistance, and health care when low-income individuals don’t meet a rigid work requirement.[1] But the report largely overlooks evidence that these proposals will harm many people — including those with health issues and children — and that they won’t do much to help people find stable employment. The report also paints a misleading picture of those who need and receive food and housing assistance and health coverage, glosses over the impact of the low-wage labor market on the need for assistance, exaggerates the evidence in claiming that assistance programs disincentivize employment, and fails to provide critical context about the Great Recession and changes in federal policies in SNAP and Medicaid when discussing caseload trends.

In particular, the CEA report ignores or understates evidence in four key ways:

- It substantially understates employment among recipients of SNAP, Medicaid, and assisted housing, painting a misleading picture of people who receive help. The CEA report only looks at whether an individual receiving assistance worked in a single month (December 2013), ignoring the fact that many workers have unstable jobs and receive help when they are between jobs. For example, about three-quarters of adult SNAP recipients who do not receive disability benefits work while receiving assistance or do so in the year before or after a typical month of benefit receipt. This figure rises to 87 percent for SNAP households with children.

- It fails to highlight key characteristics of the low-wage labor market, ignoring reasons why working families need SNAP, Medicaid, and housing assistance. Many families need help while they are working because their earnings are too low to make ends meet or afford health insurance. Low earnings can occur because of low wages, jobs that are only part time, or both. Other workers turn to assistance programs when they are between jobs, which happens frequently in low-wage jobs that feature high turnover, few benefits like sick leave that can help people retain employment, and unpredictable work hours. While the report focuses on how many people are working and working full time, it doesn’t discuss the nature of low-wage jobs, why workers work part time, often involuntarily, and why many low-wage workers experience periods of joblessness.

- It ignores data showing that many adults who receive assistance through SNAP or Medicaid face significant health and other challenges that limit the amount or kind of work they can do. The report defines everyone who doesn’t receive disability benefits as “able-bodied” and fails to discuss data that show that many such individuals have significant physical and mental health challenges that can make securing and retaining employment more difficult. The report also fails to explore the practical barriers that may prevent some individuals from working, including health conditions, need to care for a family member who is ill or has a disability, low skill levels, and lack of affordable child care, what services have addressed those barriers successfully, how much those services would cost, and how they would most effectively be delivered.

- In claiming that “self-sufficiency” is declining, it understates the impact of the Great Recession and policy decisions to support struggling working households. CEA’s own data show that the share of working-age adults receiving benefits was about the same just before the Great Recession as it had been in 1979. The number receiving SNAP and Medicaid grew sharply during the recession. In SNAP, the number of recipients began to fall when poverty finally began to recede but remains higher than pre-recession levels largely because the program does a better job at reaching families eligible for assistance, particularly working families. The share of eligible working households receiving SNAP rose from 57 percent in 2007 to 75 percent in 2016. In Medicaid, the number of beneficiaries grew during the recession and then as a result of the Affordable Care Act’s (ACA) Medicaid expansion, which 32 states including the District of Columbia have implemented.

In attempting to build support for harmful work requirements, the CEA report relies on at least three dubious conclusions:

- It oversells the “success” of work requirements in cash assistance programs and glosses over the harm that accompanied them. The report excludes longer-term follow up data — readily available from a 2001 study — that show that at the end of five years, employment gains from work requirements in cash assistance programs for families with children had faded. The report also excludes rigorous evidence that the work programs increased rates of deep poverty (income below half the poverty line), and it leaves out any meaningful discussion of research showing poor employment outcomes for TANF recipients with serious barriers to employment. Lastly, it glosses over evidence that cash assistance recipients whose assistance is taken away due to work requirements often have serious disadvantages, including physical and mental health issues, low skill levels, and domestic violence issues.

- It overstates the problem of work disincentives in basic assistance programs. The report uses its exaggeration of this matter to dismiss the benefits of strengthening work supports as a way to increase employment rates and help families.

- It uses research showing the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) has strong positive effects on employment to argue for stronger work requirements, which is misleading given the large differences between the two policies. The EITC and other earnings supplements provide a positive work incentive and concrete assistance for working families. Work requirements take away assistance from families in need when they aren’t working, often hurting those that face real barriers to employment.

The CEA report substantially understates the extent to which recipients of SNAP, Medicaid, and housing assistance work, painting an incomplete, and ultimately misleading, picture of people who need and receive help.

By looking at work among adults in a single month while they are receiving assistance, the CEA substantially overstates the extent of their joblessness, as large numbers of recipients who aren’t working have recently worked or will work soon. A longer-term CBPP analysis of SNAP recipients shows that in a typical month in mid-2012, some 52 percent of adult recipients not receiving disability-related benefits were working — but that 74 percent worked in the year before or after that month.[2] And 87 percent of SNAP households with children included someone who worked in the year before or after a typical month of benefit receipt. (These data come from the Census Bureau’s Survey of Income and Program Participation.)

Our longer-term analysis examined adults who weren’t receiving disability benefits and who participated in SNAP for at least a month in a period of almost 3.5 years. This allowed us to observe their work both while they participated in SNAP and in the months when they did not, and to observe employment among SNAP participants over a longer period.

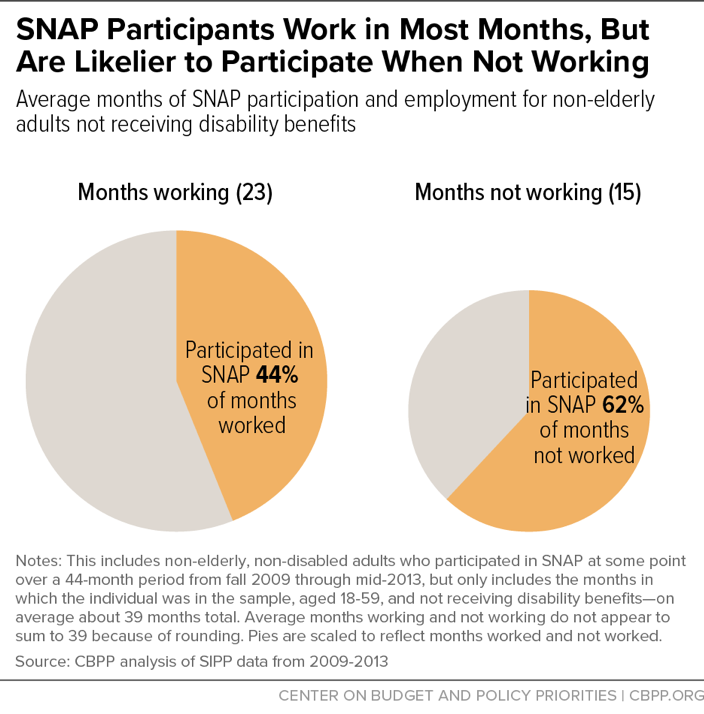

These adults worked most months, but they were more likely to participate in SNAP in the months when they were out of work and their income was lowest. These adults participated in SNAP in about 44 percent of the months that they were working, and in 62 percent of the months in which they were not working. (See Figure 1.) This helps explain why a simple snapshot analysis that focuses only on work in a single given month while people are receiving SNAP will show them working less than they do over time: many of them are workers who temporarily receive SNAP when they are between jobs.

The basic characteristics of low-wage jobs are well known: low-paid jobs often don’t last; low-wage industries tend to expand and shrink their workforces frequently based on demand; and low-paid workers often lack the paid leave or reliable child care that can help a worker keep her job. These realities help explain why many workers need assistance while they are working and when they are between jobs. Yet the CEA report includes no discussion of the low-wage labor market and how its realities can make it hard for a worker to meet rigid work requirements.

Recent work by economists Kristen F. Butcher and Diane Whitmore Schanzenbach[3] used the Census Bureau’s Current Population Survey to show that the occupations of SNAP or Medicaid recipients who work at least part of the year feature instability and low wages overall (not just for SNAP or Medicaid recipients). These occupations include personal care and home health aides, maids and housekeepers, dishwashers, food preparers, and laundry and dry cleaning workers. Looking at all workers in the ten occupations most prevalent among SNAP recipients, the researchers found that these workers faced more periods of joblessness and were less likely to be stably employed from year to year than better-paid workers in other occupations. The researchers conclude, “Together, these results suggest that it will be difficult for individuals who work and participate in benefits programs to meet proposed work requirements in the private sector alone. Although employment levels are high among many of these types of workers, employment volatility is also quite high.”[4]

While this study came out after the CEA released its report, data on the most common industries and occupations of SNAP recipients are not new,[5] nor is the evidence that low-wage jobs have higher turnover.[6] Government data sources show that low-wage workers are far less likely to have access to paid sick leave or paid family leave.[7]

The CEA report notes that some recipients work fewer than 30 or 40 hours per week in the month they are receiving assistance. But CEA’s discussion of workers’ hours leaves out key reasons that workers — especially those in low-paid jobs — often have to work part time and how much their hours fluctuate, due to their employers’ decision or other circumstances. For example, a CBPP analysis of Census data for 2016 shows that of the 10 million workers in families that reported participating in SNAP, 1.8 million, or 18 percent, reported working some full-time weeks but also some part-time weeks.[8] When asked why they worked part time in those weeks, the majority said their employers were facing slack business conditions (resulting in fewer work hours than usual) or that they could only find a part-time job during part of the year. There are other reasons that people work part time, as well, including caregiving responsibilities — either for children or family members with health conditions — and a worker’s own work-limiting health conditions.

The CEA report considers all recipients who don’t receive disability benefits as “able-bodied,” and does not present data and or cite research showing that substantial numbers of recipients who do not receive disability benefits face significant health or family challenges that limit the amount or kind of work they can do.

To receive disability benefits such as Social Security Disability Insurance or Supplemental Security Income, individuals’ conditions must meet stringent criteria. First, they must experience a severe physical impairment that has lasted for five months and is expected to last at least 12 months or result in death. This means that people with significant temporary health conditions are entirely ineligible for disability benefits, even if they are wholly unable to work. Moreover, the appeals process for disability benefits is quite lengthy, typically stretching the application process to more than two years, and thus many qualifying people with very serious conditions are in that process but have not yet been approved. And, many people with work-limiting conditions do not have a condition considered severe enough to qualify for benefits.

The difficulty of qualifying for and receiving disability benefits is well known, but CEA’s only reference to individuals who don’t receive disability benefits but may not be “able-bodied” is a one-sentence acknowledgement that some recipients may experience negative effects from work requirements and that it is important to help recipients overcome barriers to employment, which could include health conditions.[9]

It’s notable that the Administration hasn’t required states to provide any employment services — let alone specialized supports for people with health conditions — in the Medicaid work requirement proposals it has approved or proposals it has put forward in housing programs. And work requirement proposals that the Administration has supported in SNAP, such as those in the House version of the farm bill now before Congress, would provide states with wholly insufficient funding to provide job training generally, let alone the supportive services or specialized training that people with disabilities or other limitations often need.[10]

There are significant data and research documenting the extent of health issues among recipients who aren’t receiving disability benefits.

- In January 2018, the Kaiser Family Foundation issued a report showing that 5 million Medicaid beneficiaries have disabilities but do not receive disability benefits, meaning that they could be subject to work requirements under the Administration’s policies.[11]

- Data from the federal government’s National Health Interview Survey indicate that in 2015, more than two-fifths of non-elderly adult SNAP participants who reported an impairment or work-limiting disability did not receive disability benefits.[12]

- Data from the federal government’s Survey of Income and Program Participation and Current Population Survey show that in both SNAP[13] and Medicaid,[14] a large share of beneficiaries who are not working report that they are unable to work due to disability or illness, caregiving responsibilities, or because they are in school. Similarly, data from the American Housing Survey and Housing and Urban Development administrative data show that non-elderly, non-disabled rental assistance recipients who are not working are in poorer health and are more likely to have caregiving responsibilities than those who are working.

The CEA report also glosses over the real-world implementation challenges in trying to protect people with health or other challenges from losing assistance due to work requirements. In some cases, a recipient with a health condition or disability may technically be eligible for an exemption from work requirements, depending on the policies a state chooses to adopt. However, such exemptions may afford little protection. That’s because an individual must understand that she or he is potentially eligible for an exemption and then gather and submit the necessary documentation (which can be particularly difficult for those who lack health insurance). For someone who is ill or has a cognitive impairment (or someone who may be stretched thin trying to care for a family member who is ill or has a disability), these steps may prove too difficult. If the individual is able to submit the documentation, the state must review it, make a sound decision, and ensure that the decision is properly entered into the eligibility system so that the person’s benefits are not terminated.

Prior research points to ways that administrative hurdles can lead people to lose assistance and should raise concerns that new requirements that force individuals to prove they are working or meet an exemption criterion each month will result in families losing needed assistance. A recent report by the Kaiser Family Foundation (released prior to the CEA report) shows that administrative requirements often result in a loss of Medicaid coverage.[15] Similar research related to SNAP administrative requirements shows that increased requirements to submit paperwork and prove circumstances result in people losing assistance or fewer people receiving it in the first place.[16] In addition, there are studies showing that families whose TANF benefits are taken away because they don’t meet a work requirement often have significant barriers to employment — including poor health and lower educational levels — and that families whose benefits are taken away can suffer real material hardships.[17]

It should be noted that barriers are not limited to health issues. Some families have unstable housing, lack of access to affordable child care and transportation, prior criminal justice involvement that can make it hard to get a job, and the need to care for a family member who is ill or has a disability. The CEA report glosses over these real-world issues.

The CEA report uses data showing that a larger share of working-age adults received benefits from one or more benefit programs in 2016 than in 1979 to assert that “self-sufficiency” has declined and argue that work requirements are needed. But important context is missing.

First, CEA’s own data[18] show that the share of working-age adults (those not receiving disability benefits) who receive one or more benefits overall was about the same just before the Great Recession as it had been in 1979.[19]

To be sure, Medicaid and SNAP participation among working-age adults did rise somewhat over the course of the first decade of the 2000s (while receipt of cash assistance fell), but this was largely the result of the recession in the early part of the decade and policy changes that expanded access to the programs, particularly among workers and their families — a point CEA does not explain.

More recent trends can be explained in large part by the Great Recession and policy changes:

- As expected, the number of people receiving food assistance through SNAP rose substantially during the recession and started to fall when the recovery was strong enough to begin reducing poverty, but remains above pre-recession levels. This is in large part because the program is doing more to reach eligible working families than had been the case earlier in the program’s history. From 2007 to 2016, the share of eligible individuals in low-income working families who received SNAP rose from 57 percent to 75 percent. As a result, the number and share of working households participating in SNAP rose during this period.[20]

- Medicaid receipt also grew during the recession as more people lost private coverage and their income fell to levels meeting Medicaid’s eligibility criteria. Then, starting in 2014, states began to implement the ACA’s Medicaid expansion, allowing adults with incomes below 138 percent of the poverty line to qualify for Medicaid. Prior to the ACA, Medicaid did not cover adults under 65 without children unless they were pregnant or receiving disability benefits. And prior to the ACA, the median state covered parents with incomes up to only about 64 percent of the poverty line[21] — a level so low that many parents who were working for low wages often had no access to coverage through either Medicaid or their jobs.

Today, about 12 million people enrolled in Medicaid qualify by virtue of the expansion[22] and more than 25 million children in Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program are in working families. In states that expanded Medicaid, the uninsured rate for low-income working adults has fallen dramatically.[23]

Finally, while the CEA report argues that self-sufficiency has declined, only one group of adults the report examines — those age 18-49 without children — have lower employment rates today as compared to the late 1970s, while other groups have higher employment rates. Indeed, employment rates among parents with children are higher today than in 1979. Moreover, the share of poor families with children that include a worker is at least as high today as it was in the late 1970s, though lower than in the late 1990s. (See text box.)

Promising Policies Could Expand Opportunity for Struggling Workers

The economy has strengthened significantly since the end of the Great Recession and employment rates have risen across different groups of working-age adults, including parents and childless adults, men and women, workers of different ages — and low-income adults. Since 2011, working-age adults in families with incomes below twice the poverty line (about $41,560 for a family of three in 2018) saw their employment rates rise by nearly 4 percentage points overall.a

The rising employment rates over the course of the recovery suggest that underlying economic conditions and job availability are important factors in employment rates, including among workers with low earnings.

But it also remains the case that many workers — particularly those with limited skills and education, including many who live in disadvantaged communities or are people of color — continue to have trouble finding stable jobs. The lack of good job networks especially in some communities, the reluctance of employers to hire individuals formerly involved with the criminal justice system, discriminatory hiring practices, and the lack of affordable child care can all exacerbate the difficulties some workers face in the labor market.

There are evidence-based policiesb that could help improve employment prospects for those struggling in today’s economy, without the harm that comes from taking away basic assistance and health coverage from those who don’t meet a work requirement. Promising approaches include:

- Expanding training programs that have a track record of preparing disadvantaged workers for in-demand jobs and increasing employment and earnings. While no single job training approach is a good fit for all lower-skilled and hard-to-employ workers, evidence shows that these individuals generally benefit from strategies that combine education, training, and support services. Several promising models have been shown to increase workers’ skill levels and improve their completion of education, including training programs designed for high-demand sectors of the economy, work-based learning programs, and accelerated college completion programs.

- Increasing work opportunities for people with significant employment barriers. Even in good economic times, some individuals who want to work are essentially shut out of the labor market due to barriers that can complicate their ability to find and keep a job. Subsidized employment programs with support services for disadvantaged workers, programs that provide on-site employment and training programs for public housing residents, and programs that provide life skills training have been shown to improve work rates, earnings, or both.

- Investing in work supports and benefits that boost wages and make jobs more stable. Millions of workers are in jobs that provide low pay, have unpredictable schedules, and lack key benefits such as paid sick leave. This not only causes workers’ incomes to fluctuate when they’re struggling to afford the basics, but these job features also create barriers to retaining employment and career advancement. Expansions in tax credits for low-wage workers (including for workers not raising minor children in their home), investments in affordable child care, and expansions in paid leave can improve workers’ economic security and job stability.

These evidence-based investments alone aren’t enough to ensure that all workers have jobs that can support their families. But they are critical to workers’ skills and job prospects — and their families’ economic security.

CEA argues that falling TANF caseloads and evidence from pre-TANF welfare-to-work experiments show that work requirements are effective at improving employment. However, the report ignores countervailing evidence. In particular, the report:

- Overstates employment impacts of welfare-to-work programs. While evaluations of programs that imposed work requirements on welfare recipients found generally modest, statistically significant increases in employment early on among recipients subject to the requirements, those increases faded over time. Within five years, employment among recipients not subject to work requirements was the same as or higher than employment among recipients subject to work requirements in nearly all of the programs evaluated.[24]

Data on welfare-to-work experiments underscore the instability of low-wage work for many families. Evaluations of welfare-to-work experiments measured the extent to which recipients who found jobs had “stable employment,” defined as being employed in 75 percent of the calendar quarters in years three through five after the pilot projects began. Stable employment was the exception, not the norm. The share of recipients subject to work requirements who worked stably ranged from a low of 22.1 percent to a high of 40.8 percent. Even when work requirements led to a rise in stable employment, the increases were modest and left most participants without steady work. In Portland, the site of the largest impact, stable employment rose only from 31.2 to 38.6 percent.[25]

- Fails to discuss real-world employment outcomes of people with significant barriers to employment. Even when special services are provided that successfully increase employment for individuals who face significant employment barriers, the vast majority of participating recipients with real challenges do not find employment, as the one study that explicitly examines the impact of work requirements on this group shows. This points to a group particularly vulnerable to the effects of policies that expand work requirements to more low-income assistance programs.[26]

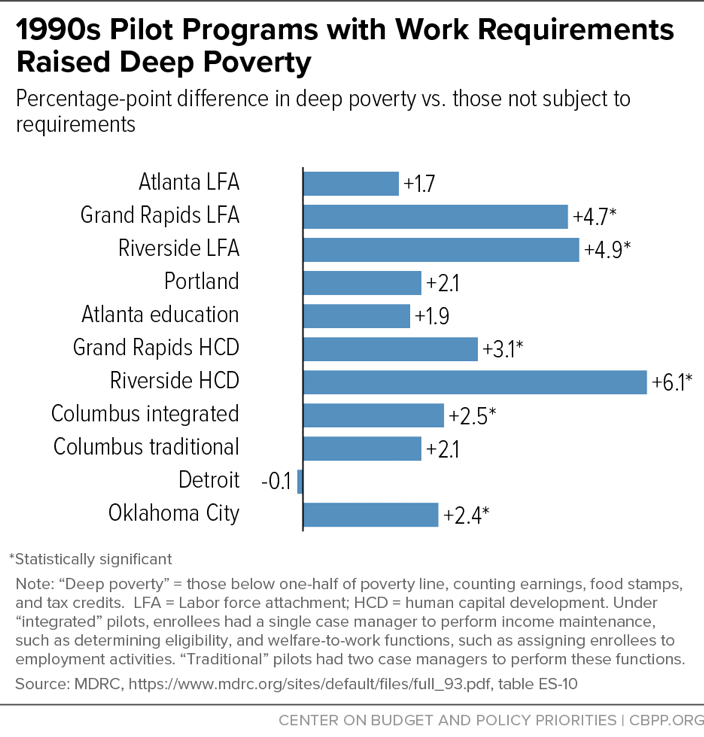

- Largely dismisses concerns that work requirements can increase hardship among those whose benefits are taken away. The report fails to discuss research that directly measured the impact of welfare reform pilot projects on deep poverty. A rigorous study of 11 pilot programs that required cash assistance recipients to participate in work-related activities in the early 1990s showed that the requirements and resulting sanctions and benefit losses raised deep poverty rates significantly in more than half the programs (6 of 11) — and in no case significantly cut deep poverty — relative to randomly assigned control groups.[27] (See Figure 2.)

While the report briefly points to the need for “careful design of work requirements to … minimize the number of households who experience negative outcomes,” it does not lay out those design elements, discuss their cost, or provide any evidence for their effectiveness.

The report also fails to discuss research that finds that cash assistance recipients whose benefits were taken away due to work requirements face significant barriers to employment and that few are able to make up for the loss in benefits through higher earnings. Multiple studies show that parents who had their TANF cash assistance benefits reduced or taken away for not meeting the work requirement were more likely than other parents leaving TANF to: face physical, mental health, or substance use issues; be fleeing domestic violence; have low levels of education and limited work experience; and face significant logistical challenges including child care and transportation. Additionally, the evidence shows that African Americans, who face more limited employment prospects because of employment discrimination, were more likely than whites to have their cash benefits reduced or taken away. The majority of families that lost benefits due to work requirements were unable to replace their cash benefits with income from work, leaving them more likely to be in deep poverty and more likely than parents leaving TANF for other reasons to face hardships such as food insecurity and utility shutoffs.[28]

When families saw their cash assistance reduced or terminated in these programs because they were unable to meet a work requirement, they continued to be eligible for SNAP and Medicaid. If these benefits are taken away, the harm families face could be significantly more pronounced.

The report overstates the extent to which basic assistance programs result in adults working less than they otherwise would. It points to situations where a family that increases its earnings would lose a very large share of that increase due to offsetting reductions in multiple programs such as TANF, food assistance, rent subsidies, and WIC, but later concedes that such situations are relatively rare because few households participate in all of the programs.

The report also concedes that although disincentives to work (termed “effective marginal tax rates”) are only rarely large, the cases when they are large mostly affect workers who are already working significant numbers of hours, generally more than 20 hours a week. Thus, the disincentive principally affects how many hours someone works, not whether they work at all. Indeed, the CEA report shows that for those not currently working, going to work would generally raise their net income significantly, and that for families with children, going to work can increase income by more than the earnings gain because the family becomes newly eligible for the EITC.

In advancing its policy prescription — to take benefits away when people don’t work — the CEA report fails to explore the barriers that may prevent some individuals from working despite wanting to do so, what services could address those barriers successfully, how much those services would cost, and how they could most effectively be delivered.[29] The report ignores both the cost[30] of operating high-quality employment programs (saying work requirements can be imposed “without necessarily increasing spending”) and the harm done when housing assistance, food assistance, and health care are taken away from needy individuals and families, including adverse effects on children.

Moreover, the report rejects the idea that expanding the EITC could be a more effective means for improving employment outcomes than expanding work requirements. It cites cost and concerns that the EITC increases marginal tax rates for those families whose earnings put them in the range where the EITC is phasing down. The report does not even recommend a larger EITC for workers who aren’t living with minor children, despite past bipartisan support for such a policy, including from House Speaker Paul Ryan. This group of workers has access to only a very small EITC today (as compared to a more robust EITC for workers with children). Thus, the large positive work incentive provided by the EITC for parents is not in place for childless adults, the group whose employment rate the CEA report seems most concerned about. And, the cost of expanding the EITC for such workers would be a tiny fraction of the cost of the tax cuts enacted at the end of 2017.

The report argues that research showing that the EITC has strong positive results on employment and long-term outcomes for children provides support for imposing work requirements — an entirely different policy — on large numbers of people. The report draws an unsound conclusion from the available evidence. Requiring work (backed up by harsh penalties) and encouraging and rewarding it, as the EITC does, are two distinct approaches, making it misleading to use evidence from one policy to support the implementation of the other:

- Unlike the EITC, which rewards people with a supplement to their earnings if they choose to work, work requirements take basic assistance and health care away from those who don’t meet a work requirement. Thus, work requirements carry significant risks of harming needy families that do not arise with the EITC.

- There is substantial evidence of the positive impacts of the EITC (and other earnings-supplement policies) on employment outcomes, which has led conservatives and progressives alike to advocate for expanding the EITC for adults not raising minor children as a tool for increasing employment as well as for helping struggling workers make ends meet.

- A highly regarded study by University of Chicago economist Jeffrey Grogger, which CEA references but does not fully describe, found that welfare reform (which implemented work requirements) accounted for just 13 percent of the total rise in employment among single mothers in the 1990s. The EITC (which policymakers expanded in 1990 and 1993) and the strong economy were much bigger factors, accounting for 34 percent and 21 percent of the increase, respectively.[31]

- Evidence is clear that earnings supplements such as the EITC can have beneficial effects on children’s education and other outcomes. There is similar evidence that SNAP,[32] Medicaid,[33] and housing assistance[34] have positive impacts on children’s well-being, both in the near and long term. There is not similar evidence for work requirements. Indeed, one rigorous study in the 1990s was designed to reveal how work requirements — separate from earnings supplements — affect children’s well-being.[35] The experiment, part of the Minnesota Family Investment Program, compared three policies: traditional cash assistance, cash assistance plus earnings supplements, and cash assistance plus earnings supplements and a work requirement backed by financial penalties if parents did not meet the requirement. Compared to traditional cash assistance, the earnings supplements lowered poverty and significantly raised children’s school performance and engagement. While adding work requirements on top of earnings supplements increased parental employment (though, as in other studies, these positive employment effects faded for most groups over time), it also resulted in significantly less positive child behavior, more material hardship, more frequent moving from home to home, and decreased parental warmth. The findings “suggest that increases in income may benefit children’s academic functioning and that increases in employment alone are generally neutral but may have negative effects on selective aspects of children’s positive behavior,” evaluators concluded. The negative impacts of work requirements on children could be larger if the family not only loses cash assistance, but also sees reductions in food assistance and if parents must go without health care.