BEYOND THE NUMBERS

Tracking the Senate Floor Debate on Health Care Repeal

Last night’s vote — and the months of debate that preceded it — show that the American people don’t want to move backwards on health care. Read more here.

Thanks for following the debate on our tracker. There’s more work to do to strengthen our health care system and continue the task of making health insurance affordable and accessible for all. You can continue to follow our work on health care on our website, via email, and on Facebook and Twitter.

Update, 8:25 PM: Republican Health Bills Would Expose Tax Credit Recipients to More Tax Liability, Discourage Enrollment

Complaining earlier today about the Affordable Care Act (ACA), Senator Ron Johnson, a Wisconsin Republican, told a story of a couple who had to repay the IRS $15,000 in ACA premium tax credits that they received. That same couple, however, could fare worse under the House-passed and Senate bills to repeal the ACA.

Under the ACA, the Treasury Department pays premium tax credits directly to insurers throughout the year to offset monthly premiums for individuals and families who are eligible for the credits. The marketplaces determine the amount of the monthly credit based on applicants’ estimate of their income for the coming year. The marketplace verifies these estimates using tax and wage databases. At the end of the year, the taxpayer reconciles the premium tax credit he received in advance with the actual income he reported on his tax return. If he got too little of an advance credit, the taxpayer claims an additional credit. If the taxpayer received too much of a credit, he must repay the overpayment, up to an income-based cap, which ranges from $300 to $1,275 for single people and $600 to $2,550 for families. However, there’s no cap on repayment for taxpayers whose incomes end up exceeding 400 percent of the poverty line, which is the eligibility limit for the credit.

That’s what happened to the family in Senator Johnson’s story. They received too much of a credit and needed to repay it. Because their income exceeded 400 percent of the poverty line (which is $65,000 for a family of two), they weren’t protected by the repayment cap and had to pay the full amount.

The House-passed and Senate Republican health bills, however, not only fail to extend the cap on repayment to higher-income people or create exceptions for good faith situations like an end-of the year bonus that boosts income over the 400 percent limit, but they remove the cap for lower-income people. They would expose everyone receiving premium tax credits to thousands of dollars in tax liability, particularly lower-income people who generally get the largest credits, and would discourage enrollment out of fear of repayment. In fact, the Joint Committee on Taxation estimated in 2016, a freestanding proposal to eliminate the caps on repayment amounts would deter 250,000 people each year from enrolling in coverage.

The Senate bill also creates a 25 percent tax penalty for an erroneous claim of the premium tax credit, compounding the risk of using the credit and, thus, guaranteeing that more people will be uninsured. Policymakers should instead pursue a bipartisan approach that could extend the repayment cap to additional people — and help families like the one that Senator Johnson described.

Update, 8:00 PM: Coverage Losses Under “Skinny” Plan Aren’t Skinny at All

The Senate is poised to consider a “skinny” bill to repeal the Affordable Care Act (ACA), the major components of which would leave an estimated 16 million more people uninsured next year, according to the Congressional Budget Office (CBO), while hiking premiums in the individual market by about 20 percent. And if Senate Republican leaders use the skinny bill only to advance their effort for comprehensive repeal legislation, as they have made clear that they plan to do, the coverage losses could be far larger.

The CBO analysis examined the effect of repealing the ACA’s individual and employer mandates as well as repealing the medical device tax. The skinny bill has changed since then — it reportedly repeals the employer mandate only partially, doesn’t repeal the medical device tax, defunds Planned Parenthood for one year, and provides money for community health centers. But those changes wouldn’t much affect the troubling coverage losses and premium increases that CBO estimates, which largely result from the repeal of the individual mandate — an undisputed component of skinny repeal.

Repealing the individual mandate to have coverage or pay a penalty would immediately lead some people, many of them relatively healthy, to drop coverage or not newly enroll in it. That would destabilize the individual market by making the pool of people with coverage sicker, on average, driving up premiums and endangering the protections for people with pre-existing medical conditions over time.

And the losses wouldn’t only be in the individual market. With repeal of both mandates, some 6 million fewer people would have employer-sponsored coverage in 2018, according to the CBO’s preliminary analysis.

No matter how “skinny” this bill allegedly is, Senate Republican leaders have made clear that their true goal is to pass something, anything, that will advance health legislation to a conference with the House, which passed its own repeal-and-replace bill in May. Senate Republicans John McCain, Lindsey Graham, Ron Johnson, and Bill Cassidy said at a Thursday press conference that they would vote for the skinny bill only if the conference committee, which would draft the final legislation on which both chambers would then vote, would consider far more sweeping health care changes. That means all the unskinny proposals, and the coverage losses they would cause, are very much alive. The House-passed bill to repeal and replace the ACA would raise the number of uninsured by 23 million, CBO estimates.

Updated, 4:45 PM: Cassidy-Graham Amendment Would Bring Drastic Cuts, Not State Flexibility

Senators Bill Cassidy and Lindsey Graham say their amendment to the GOP health bill focuses on increasing state flexibility to run their Medicaid programs and equalizing federal Medicaid payments and insurance subsidies across states rather than cuts, but as our new paper explains, it would drastically cut both Medicaid and marketplace financial assistance in every state — including Nevada, whose Senator Dean Heller just signed on to the bill. Millions of people would lose coverage, just as under the House-passed bill to repeal the Affordable Care Act (ACA) and the Senate’s Better Care Reconciliation Act.

The Cassidy-Graham amendment would:

- Eliminate premium tax credits and cost-sharing reductions that help moderate-income marketplace consumers afford coverage and care, and eliminate the ACA’s enhanced federal funding match for Medicaid expansion starting in 2020.

- Replace the marketplace subsidies (premium tax credits and cost-sharing reductions) and Medicaid expansion funding with a block grant set at funding levels well below what states would get under current law. States apparently could use these funds for a broad range of health care purposes, not just coverage, with essentially no guardrails or standards to ensure affordable, meaningful coverage. After 2026 block grant funding would end altogether.

- Maintain the Senate bill’s provision to convert virtually all of Medicaid to a per capita cap, with large and growing cuts to federal funding for seniors, people with disabilities, and families with children.

- Create significant near-term uncertainty and disruption in the individual market. For insurers, the Cassidy-Graham amendment would have much the same consequences as proposals to repeal the ACA with no replacement. In the near term, insurers would most likely impose very large rate increases and, in some cases, exit the market.

Despite Senator Heller’s co-sponsorship of the amendment, it would fail in the long run to meet his commitment to protect coverage for Nevadans, as he pledged in a June press conference: “I cannot support a piece of legislation that takes insurance away from tens of millions of Americans, and hundreds of thousands of Nevadans.”

Read the full paper here.

Updated, 2:00 PM: Parliamentarian Rules Against Latest Attempt to Repeal ACA Consumer Protections Through Reconciliation

The Senate parliamentarian has determined that the latest Republican attempt to repeal the Affordable Care Act (ACA)’s protections for people with pre-existing conditions violates the rules for Senate reconciliation bills. That means that Senate Republicans would need 60 votes to keep this provision in their bill — and they also would need 60 votes to include this, or likely any similar, provision in a final House-Senate conference agreement on health legislation.

The Senate repeal-and-replace bill (the Better Care Reconciliation Act) includes a provision that would dramatically expand the scope of so-called “1332” waivers states can obtain under the ACA, removing the guardrails that ensure that these waivers don’t make coverage less affordable or add to the uninsured. In effect, this provision would enable states to eliminate or weaken the ACA’s rules that prevent insurers from excluding coverage for core services (like maternity care, mental health and substance use treatment, and prescription drugs), prohibit annual and lifetime limits on coverage, and require limits on consumers’ out-of-pocket costs. As a result, many people with pre-existing conditions would lose access to needed care.

However, the parliamentarian has now ruled that this provision violates the “Byrd rule,” which allows senators to block provisions of reconciliation bills that are “extraneous” to reconciliation’s basic purpose of implementing budget changes. That means that Senate Republicans would need 60 votes to keep this provision in any version of their bill.

What’s more, the parliamentarian’s ruling strongly suggests that other, similar provisions seeking to gut the ACA’s core consumer protections and protections for people with pre-existing conditions — what conservatives have referred to as its “Title I” rules — would also violate the Byrd rule. For example, while the parliamentarian has not ruled on the so-called Cruz amendment (or the House bill’s so-called MacArthur amendment), today’s ruling raises serious doubts about whether these proposals could survive a Byrd rule challenge.

Importantly, the Byrd rule also applies to reconciliation bill conference agreements, as our new guide to the rules surrounding the conference process explains. Thus, any provision in a Senate bill that the parliamentarian has ruled would be subject to a 60-vote challenge would also be subject to a 60-vote challenge if it’s included in a final House-Senate conference report.

Updated, 1:20 PM: Reminder: House Health Bill Raises Out-of-Pocket Costs by Thousands of Dollars for Millions of People

The House-passed bill to repeal the Affordable Care Act (ACA) — the basis for the Senate debate and the starting point for a House-Senate conference committee if the Senate passes any bill — would raise total out-of-pocket costs for marketplace consumers by an average of $3,600 in 2020. Total cost increases would be even larger for people who have lower incomes, are older, or live in high-cost states: in 15 states, average increases would exceed $4,000.

Here’s a refresher on why the House approach is so extreme:

- Its tax credit isn’t adequate for most people in most states to afford coverage. The House bill would provide flat tax credits varying only by age: $2,000 for people under 30, $2,500 for people age 30 to 39, $3,000 for people age 40 to 49, $3,500 for people age 50 to 59, and $4,000 for people age 60 and older. While the House plan would give a credit to older people that’s twice as large as for younger people, it allows insurers to charge premiums that are five times higher than those of younger people.

- Unlike the ACA’s credit, the House credit isn’t flexible. Tax credits would be the same regardless of the local cost of premiums and would generally be the same regardless of income (although they would phase out at higher income levels). In contrast, the ACA credit is based on the cost of an actual plan in the marketplace for someone’s age in the consumer’s geographic rating area, and people contribute based on their income. Some of the House bill’s biggest losers would be consumers in Alaska, Arizona, Tennessee, and West Virginia, where premiums are among the highest and the tax credit cuts would be the deepest.

- Losses would grow over time. Under the House plan, tax credits would grow at the rate of inflation plus 1 percentage point, no matter how quickly premiums rose in a particular year or state. Under the ACA, on the other hand, the credit absorbs much of the premium increase to keep premiums stable.

- Out-of-pocket costs would rise. Like the Senate’s Better Care Reconciliation Act, the House bill would eliminate cost-sharing subsidies that reduce out-of-pocket costs for people with income below 250 percent of the poverty line. Without these subsidies, average marketplace deductibles would increase by about $2,800 for single people with incomes below $18,000, by about $2,300 for single people with incomes between $18,000 and $24,000, and by about $600 for single people with incomes between $24,000 and $30,000. In addition, the bill effectively eliminates the ACA’s requirement that insurers offer consumers the choice of a lower-deductible plan, which the Congressional Budget Office projects would lead many insurers to offer only high-deductible options.

Updated July 27th, 1:15 PM: Bipartisan Group of Governors Oppose “Skinny Repeal”

In a bipartisan letter last night, ten governors asked Senate leaders to set aside legislation to repeal the Affordable Care Act (ACA) and instead focus on making health insurance more affordable and stabilizing the individual market. Citing a recent floor speech by Senator John McCain, the governors asked the Senate to return to regular order and work across the aisle on practical solutions.

The governors noted that the House-passed ACA repeal bill (and similar bills) now under debate in the Senate wouldn’t meet the goals of affordability and market stabilization. In particular, the bill’s Medicaid provisions would “shift costs to states and fail to provide the necessary resources to ensure that no one is left out, including the working poor or those suffering from mental illness or addiction.” They also urged the Senate to reject efforts to amend the bill into a “skinny bill,” which would “accelerate health plans leaving the market, increase premiums, and result in fewer Americans having access to coverage.”

The governors concluded by urging “senators and governors of both parties to come together to work to improve our health care system. We stand ready to work with lawmakers in an open, bipartisan way to provide better insurance for all Americans.”

It’s unsurprising that governors of both parties oppose congressional GOP plans to repeal the ACA and radically restructure and cut federal Medicaid funding for their states. They recognize the harmful results: hundreds of billions of dollars in lost federal funding; large increases in the number of uninsured; and setbacks to states’ efforts to combat the opioid epidemic, expand access to preventive care, improve rural health care, and institute innovative delivery system reforms in their Medicaid programs to raise quality and lower costs.

Now, the question is whether Senate Republican leaders — who have so far ignored the strong opposition from physicians, nurses, hospitals, patient advocates, and other experts — will set aside their deeply damaging approach and work across the aisle to stabilize insurance markets and improve affordability, as governors from both parties ask.

Update, 6:30 PM: House-Passed Health Bill — Now Under Debate in Senate — Still Can’t Be Fixed.

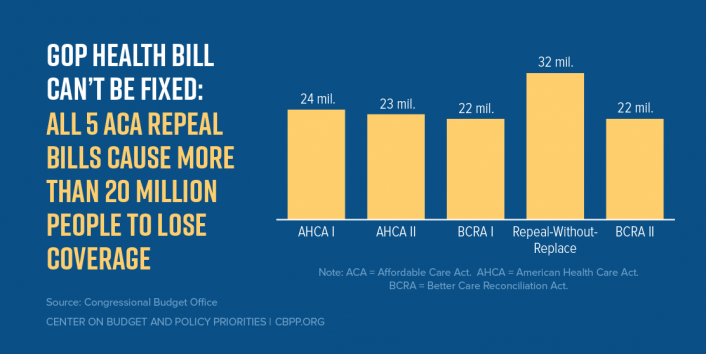

In votes last night and this afternoon, Senate Republican leaders couldn’t rally a majority behind two Senate proposals that would take health coverage away from over 20 million Americans, raise premiums, and gut protections for pre-existing conditions. That leaves the fundamentally flawed House-passed bill to repeal the Affordable Care Act — the American Health Care Act (AHCA) — as the basis for the Senate debate.

While the Senate won’t likely vote on the House bill at the end of this process, it’s important for another reason. If the Senate passes any repeal bill that goes to a House-Senate conference among Republican leaders, the AHCA would be the likely “template” for final action. In fact, Senate Majority Whip John Cornyn acknowledged earlier today that that’s the goal of Senate Republicans.

Given that it’s been several weeks since the House passed its bill and we’ve seen multiple iterations of ACA repeal bills since, here’s a reminder: the bill shares the same core harmful features as the bills the Senate has already voted down, and many that are worse.

Like the Senate bill, AHCA slashes programs that help people get health coverage, using most of the savings to pay for tax cuts for high-income households and corporations. It would increase the number of uninsured by 23 million (see chart) and cut federal Medicaid spending by $834 billion.

Specifically, the AHCA would:

- Effectively end the ACA Medicaid expansion for low-income adults;

- Cut and radically restructure Medicaid funding for seniors, people with disabilities, and families with children;

- Increase premiums, deductibles, and other out-of-pocket costs for millions of people with individual market coverage;

- Let states allow insurers to offer plans with large benefit gaps and charge higher premiums to people with pre-existing health conditions; and

- Give millionaires tax cuts averaging more than $50,000 per year, partly at the expense of the Medicare trust fund.

The House bill isn’t fixable. Virtually every provision causes people to lose coverage, makes coverage less affordable or less comprehensive, or cuts taxes for high-income people.

Update, July 26th, 9:35 AM: Senate Repeal Bill Would Cause Millions to Lose Coverage, Collapse Individual Market

The Senate is expected to vote later today on a version of a vetoed 2015 bill to repeal most of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) without a replacement. The bill would cost even more people their health coverage, raise premiums in the individual market even higher, and inflict even more damage to insurance markets than prior ACA repeal bills that have failed to gain enough support in the Senate to pass.

Specifically, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) analysis of the bill found that, by 2026, it would:

- Increase the number of uninsured by 32 million

- Double premiums in the individual market

- Cause the individual market to virtually collapse, leaving 75 percent of Americans living in areas without any individual market insurer

At the same time, it would provide large tax cuts for the wealthy and corporations.

The Republican repeal plan supposedly aims to create political pressure for policymakers to enact a replacement bill within two years, after which the ACA’s provisions expanding Medicaid and helping families afford individual market insurance would be eliminated. But the past six months have clearly shown that any Republican "replacement" plan would still cause tens of millions to lose coverage, leave millions more paying higher premiums and out-of-pocket costs, and lead to deep and growing cuts to Medicaid.

Update, 8:15 PM: Portman Amendment Doesn’t Fix Flawed Bill, Cruz Amendment Makes It Worse

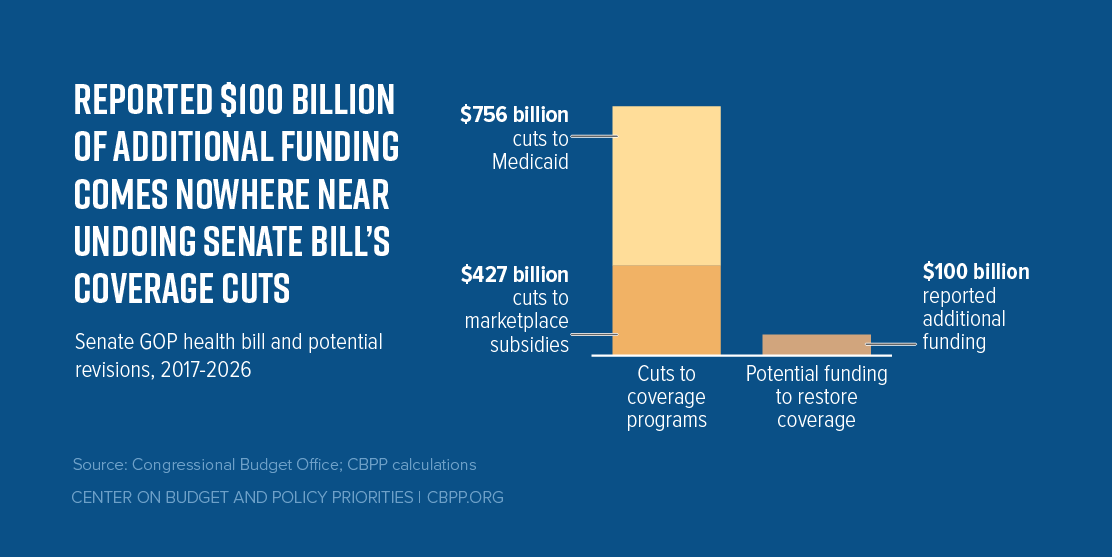

Senate Republicans will reportedly vote tonight on an amended version of the Better Care Reconciliation Act (BCRA). The Congressional Budget Office estimated that its most recent version would cause 22 million people to lose health insurance in 2026 and cut Medicaid and marketplace subsidies by nearly $1.2 trillion. The amended version makes two changes, neither of which improves the bill.

First, it includes an amendment from Ohio Senator Rob Portman reportedly intended to help maintain coverage for people losing Medicaid expansion coverage as a result of the Senate bill. The amendment adds $100 billion to the BCRA’s state stability fund and gives states a new option to draw down Medicaid funds at their regular matching rate to provide supplemental coverage to people losing Medicaid expansion coverage. But the funds added to the stability fund wouldn’t come close to undoing the bill’s harm: in fact, they amount to 8 percent of its cuts to federal funding for coverage programs (see figure). Nor would the new Medicaid option address the harm to people losing Medicaid expansion coverage under the Senate bill.

Second, the amended version includes a provision backed by Senator Ted Cruz, which would eviscerate protections for people with pre-existing conditions in the individual market and drastically raise premiums for comprehensive plans that cover critical benefits. The Cruz amendment would allow any insurer offering at least one plan satisfying Affordable Care Act (ACA) market reforms and consumer protections to also sell other, non-ACA plans in the individual market that do not comply with these standards. (For example, non-ACA plans wouldn't be required to cover people with pre-existing conditions or charge them the same premiums as healthier people or to cover benefits such as maternity care, mental health and substance use disorder treatment or prescription drugs.) The result: an insurance market that divides sharply into healthy and unhealthy risk pools, driving up premiums for ACA plans to unaffordable levels.

A new Avalere report finds that a mid-July version of the Cruz amendment would result in premiums for ACA plans in 2022 rising by 39 percent compared to current law. Avalere finds that the premium hike would be even greater — 86 percent — if not for state stability funding included in the Senate bill, $70 billion of which was added to counteract the problematic effects of Cruz and all of which expires after 2026.

Original Post, July 25th, 7:15 PM:

Earlier today, the Senate passed the “motion to proceed” to begin the floor debate on its Affordable Care Act repeal proposals. While it’s still unclear exactly what the Senate will vote on and when, we’ll be posting updates here throughout the debate.

Senate Republican leaders reportedly may attempt to revive their repeal bill, the Better Care Reconciliation Act or BCRA, as soon as this evening. It’s important to note that Congressional Republicans have put forth five versions of ACA repeal. All five GOP health bills would:

- cause more than 20 million people to lose coverage,

- massively cut federal Medicaid funding,

- slash subsidies for individual market consumers, and

- eliminate crucial protections for people with pre-existing conditions.

Senate Republican leaders may make additional changes in the coming hours or days and claim that the changes will fix the bill’s core flaws. But we’ve seen this before. In both the House and Senate, Republican leaders have revised their bill and claimed that the revisions addressed its core flaws — and then the Congressional Budget Office showed that the claims were false.

The Senate health bill can’t be fixed. No senator should fall for claims that it has been.