BEYOND THE NUMBERS

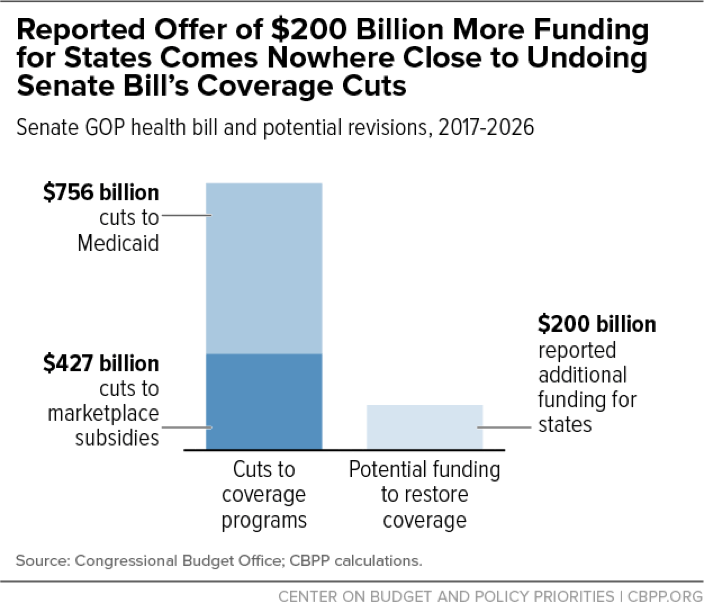

The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) analysis of the revised Senate health bill shows that the latest changes to it don’t address any of its major flaws. The bill still causes 22 million people to lose coverage, still massively cuts federal Medicaid funding (by $756 billion), still slashes subsidies for individual market consumers (by $427 billion), and still weakens crucial protections for people with pre-existing conditions.

But the CBO score doesn’t just show that the Senate bill hasn’t been fixed: it also highlights a key reason why it can’t be fixed. Even now that Senate Republicans have dropped two of the bill’s high-income tax cuts, there just aren’t enough resources to undo more than a small share of the bill’s harmful coverage cuts.

CBO estimates that the Senate bill reduces the “on-budget” deficit (which counts everything but Social Security and the Postal Service) by $286 billion more over ten years than the House-passed bill. Senate reconciliation rules require that the final bill reduce on-budget deficits by at least as much as the House bill, meaning Senate leaders can use $286 billion at most to restore cuts to coverage programs.

But the bill’s cuts to Medicaid and marketplace subsidies total nearly $1.2 trillion over ten years — more than four times the available savings. That means that even if Senate Republicans used every available dollar to restore cuts, they could reverse less than 25 percent of them.

And that calculation considerably overstates how much progress they could make:

- It’s by no means certain that Republicans would or could devote additional spending to reducing coverage losses. On the contrary, the newest version of the Senate bill added over $100 billion in new costs (for example, for grants for substance use treatment and to expand tax breaks for health savings accounts). But CBO determined that the additional money made no difference in coverage losses in 2026: both the original and revised Senate bills would cause 22 million people to lose coverage.

- The so-called “Cruz amendment,” which the CBO score doesn’t reflect, would likely further increase the bill’s costs by raising premiums and hence costs for premium tax credits. That would reduce the available savings, perhaps substantially. And trying to mitigate the amendment’s harm to people with pre-existing conditions would use up even more funding.

- Much of the Senate bill’s harm stems from its changes to rules and program structure, not just its cuts. For example:

- Even without the Cruz amendment, the bill would allow insurers to once again exclude coverage for basic services like maternity care, mental health, and substance use treatment.

- In addition to cutting federal Medicaid funding, the bill radically restructures all of Medicaid, converting it to a per capita cap that would force states to make large and growing cuts to Medicaid services and eligibility over time and make Medicaid funding far less responsive to need.

Extra funding for state grants isn’t a way around the Senate bill’s basic math. Senate Republican leaders and the Trump Administration are reportedly discussing adding $200 billion in state grants to the Senate bill. Administration officials have suggested that states could use these funds to provide a “coverage wrap” for those losing Medicaid coverage under the bill, which would supplement the unaffordable private plans that the bill now offers them.

But, as we’ve explained, there’s no free lunch. If Senate Republicans want to maintain coverage for many or most of the 15 million people losing Medicaid coverage under the bill, some combination of federal and state governments will have to restore much or all of the bill’s $756 billion in Medicaid cuts. In fact, since private coverage costs more than Medicaid coverage, providing affordable private coverage to this group would likely cost more than $756 billion. Likewise, maintaining affordable coverage for low- and moderate-income marketplace consumers would require restoring the bill’s $427 billion in cuts to subsidies. As the math demonstrates and the figure below shows, $200 billion would fall dramatically short.