BEYOND THE NUMBERS

States Must Address Workforce Discrimination to Promote Opportunity for College Graduates of Color

State spending cuts to public colleges and universities have forced many students to assume onerous debt or abandon higher education altogether, as we’ve explained. For students of color, the harms of carrying this debt are compounded by racial discrimination in the workforce. While the benefits of achieving a college degree are significant, college graduates of color who can afford, and who graduate from, college often don’t share equally in these benefits due largely to racial discrimination in the workforce. State lawmakers can take steps now to reduce this discrimination to promote opportunity for students from all backgrounds

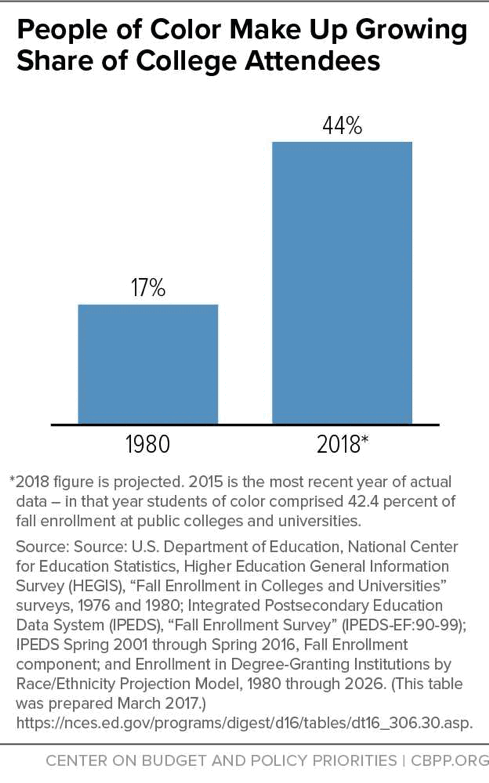

More people of color attend college than ever before; the share of students on public college campuses who are people of color has risen from 17 percent in 1980 to more than 40 percent today (see chart).

But states can’t take advantage of these significant gains in college attendance to strengthen their economies if they fail to address workplace discrimination, which keeps people from fully participating in the workforce.

In 2017, black college graduates with a bachelor’s degree earned about 22 percent less per hour on average than their white peers. For Latinx graduates, the difference was 16 percent. An Economic Policy Institute study noted that, for black graduates, this gap had risen since the late 1970s after taking account of education levels and job experience. Even after controlling for education and other observable factors such as age and geography, black workers experienced higher unemployment than their white peers and black and Hispanic workers were likelier to work part-time even when they wanted to work more, the Federal Reserve Board found in a 2017 study.

These gaps persist, in part, because employers are devaluing the potential of qualified workers of color due to their race or ethnicity. A body of research has emerged to explain the impact that discrimination plays in hiring and wages.

- In a 2014 study, researchers created resumes of hypothetical black and white applicants from elite, highly selective colleges and less prestigious state schools. After submitting the resumes to over 1,000 job listings, black job applicants who had graduated from highly selective private institutions received responses from employers at a rate nearly a third lower than their comparable white counterparts. In fact, white students who attended less prestigious state schools received about the same response rates from potential employers as did black students applying from elite institutions. Even more striking, when employers did respond to black applicants, they offered jobs with lower starting salaries than those offered to the applicants’ white peers.

- A 2018 study of salary negotiations found that employers expected applicants of color to negotiate less than their white peers and effectively penalized them when they tried to negotiate, viewing applicants of color as being more “pushy” and, in turn, offering them lower initial salaries.

- And trends may not be improving. In a meta-analysis from 2017, researchers analyzed nearly 30 years of research on hiring discrimination and concluded that — even after controlling for variables such as education, occupational type, or gender — “African Americans remain substantially disadvantaged relative to equally qualified whites, and we see little indication of progress over time.” While the studies analyzed seemed to indicate less discrimination in hiring for Latinx workers, the improvement was modest at best, the report noted.

For people of color with college credentials to access the full benefit of these degrees, states must take steps to reduce workforce discrimination. Among other things, state lawmakers should tighten state employment discrimination laws to protect workers from illegal practices and ensure that workers can reasonably seek recourse.