BEYOND THE NUMBERS

Most states have most or all of the “rainy day” funds — reserves to use when recessions or other unexpected events cause revenue declines or spending increases — needed to weather a moderate recession, but they still face many risks, according to the bond rating agencies Standard & Poors and Moody’s. States should act now to better prepare for the inevitable next downturn.

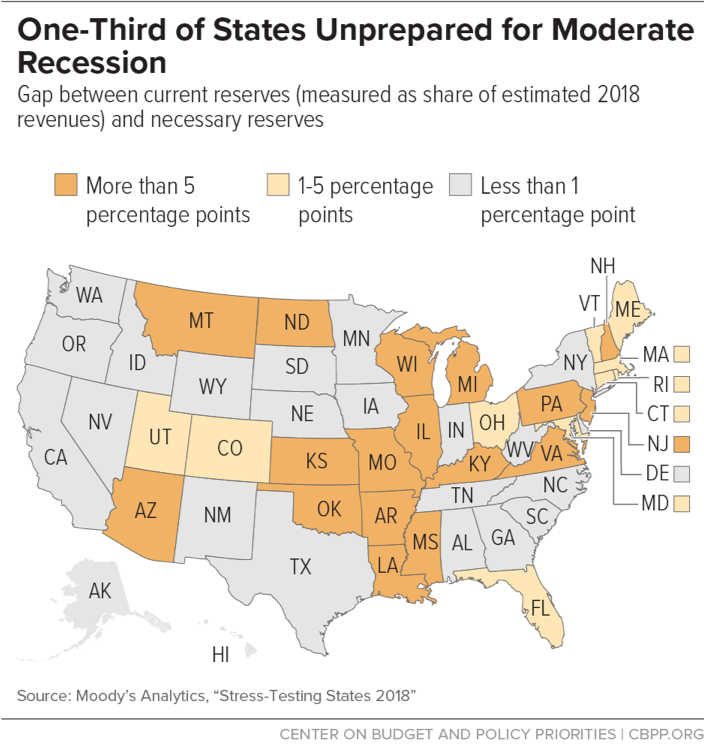

About a third of states are unprepared for even a moderate downturn, reports from these rating agencies find. (See map.) And if the nation faces another severe downturn — one that affects state budgets as much as the Great Recession did — only 14 states are prepared, according to Moody’s. Moreover, whether the next recession is moderate or severe, the federal government may be less helpful in reviving state economies, as growing federal deficits fueled in part by the 2017 tax law could make policymakers less willing to give states more funds to help offset their own budget problems.

Rainy day funds have proved their worth; in each of the last two recessions, they enabled states to avert over $20 billion in service cuts, tax increases, or both. Yet these reserves filled only a modest share of states’ budget gaps, so states would have weathered the storms better with bigger rainy day funds.

States can take several concrete steps now to improve their rainy day funds:

- Put more money into them. Many states collected higher-than-expected revenues in fiscal year 2018, and this trend is apparently continuing. If so, states would be wise to set aside some of these funds in reserves.

- Ease rules that make it hard to make deposits in good times. Most states place a low priority on replenishing their funds, depositing only whatever surpluses remain at the end of the year. States could integrate rainy day fund transfers into the budget as part of an overall reserve policy that puts a high priority on saving.

- Loosen overly restrictive caps on the size of rainy day funds. Rainy day funds weren’t more effective in the last downturn in part because half the states cap them at inadequate levels, such as 10 percent of the budget or less. States with overly restrictive caps could either remove them or raise them to more adequate levels, such as 15 percent of the budget.

- Remove limits on legitimate uses of the funds. Rainy day funds are designed to address temporary revenue declines or new expenses; states generally prevent their use for permanent (that is, ongoing) spending or tax measures, which could create a future imbalance between revenues and spending. Rules in some states, however, make it unnecessarily hard to access the funds when needed, such as by requiring a supermajority vote of lawmakers or arbitrarily limiting how much of the fund a state can tap at any one time. States should remove such overly restrictive rules.

Adequate reserves are essential for states to maintain their role in building a strong, equitable economy.