BEYOND THE NUMBERS

Republican Senator Jeff Flake busted several myths about estate tax repeal, a central part of both President Trump’s and the House GOP’s tax plans, in a recent interview with Bloomberg View. He noted that the tax has shrunk significantly over the last few decades, said he was “concerned that we don’t take the deficit into account” in considering repeal, and expressed skepticism over whether repeal would stimulate the economy. He’s right on all three counts:

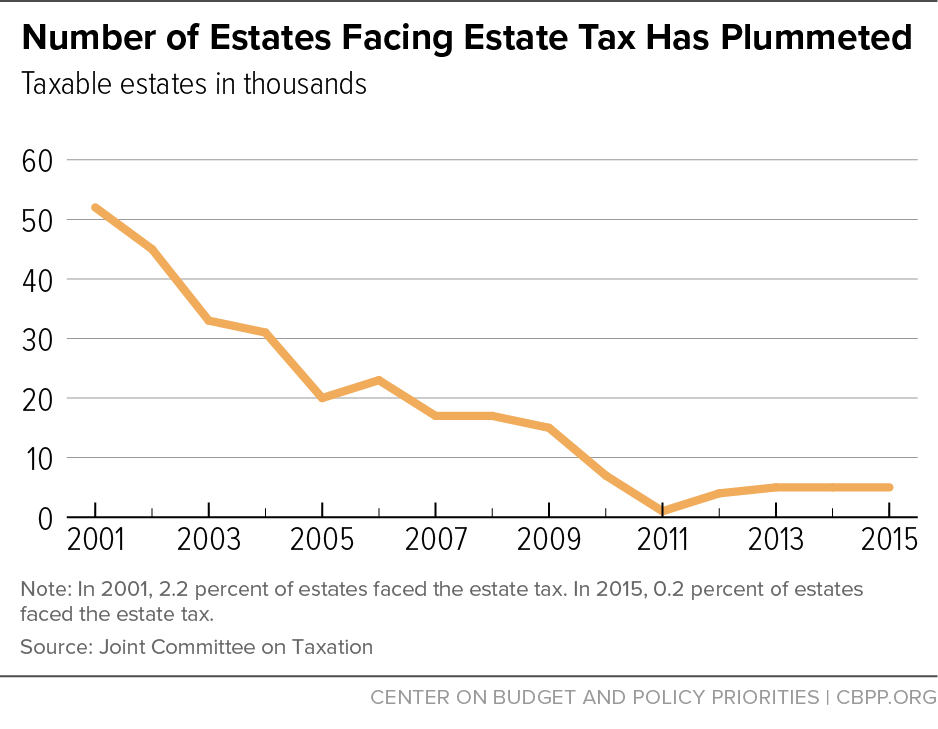

(1) Policymakers have weakened the tax so much that very few estates face it at all. Senator Flake said that Congress has “done pretty well” in changing the federal estate tax. While we disagree with the policy direction policymakers have taken with the tax, he correctly notes that they’ve weakened it significantly in recent decades.

Legislation enacted in 2001 gradually phased out the tax by raising the exemption level and reducing the rate, leading to the tax’s temporary repeal in 2010. The tax returned in 2011 but in much weaker form. Today, the first $5.49 million of a person’s wealth ($10.98 million per couple) is completely exempt from the tax and passed on tax-free to heirs, up from $650,000 per person in 2001.

As a result, the number of estates that face any estate tax has fallen by more than 90 percent, from over 50,000 in 2001 to fewer than 5,000 in 2015 (the latest year for which we have comparable data). Put another way, the wealthiest 2 out of every 100 estates faced any estate tax in 2001, but only the wealthiest 2 out of every 1,000 do today. (See chart.)

Moreover, the top statutory rate has fallen from 55 percent to 40 percent. And, primarily because of the high exemption level, the few estates that actually face the tax pay only 19 percent of the estate in tax, on average.

Because the estate tax affects only the wealthiest 0.2 percent of estates, it’s the most progressive part of the tax code. It’s also the nation’s most effective tax policy tool to mitigate the impact of large inheritances on inequality.

(2) Repeal would expand deficits. Eliminating the estate tax would cost $269 billion over ten years, before counting its greater interest costs associated with higher debt. It would be unwise for policymakers to add billions to the task of reducing long-run deficits while also worsening inequality.

(3) Claims that estate tax repeal would be an economic boon merit skepticism. Repeal proponents claim that the tax hurts the economy and that repeal would stimulate it. Yet, Senator Flake rightfully questions “whether [repeal] stimulates that much more.” In fact, eliminating the estate tax would be economically unsound. It wouldn’t substantially affect private saving, and it would greatly increase government dissaving (i.e., deficits); as a result, repeal would likely reduce the overall capital available for investment. Research also suggests that the tax may actually encourage wealthy heirs to work and save by reducing their inheritances; a Treasury Department analyst estimated that “an inheritance of $1 million, other things equal, reduces labor force participation by about 11 percent.” Estate tax repeal would encourage wealthy heirs to work less.

Senator Flake has raised important points: Congress has already drastically reduced the number of estates that the tax affects, and repeal would increase the deficit while doing little for the economy. His colleagues would do well to listen to him.