BEYOND THE NUMBERS

The Social Security and Medicare trustees will release their annual reports on the programs’ finances tomorrow and, though we don’t know how the projections may change from last year’s, we expect them to tell a similar story: Social Security and Medicare face real but manageable financial challenges and are neither unaffordable nor “bankrupt,” as critics claim.

The trustees last year estimated that Social Security’s combined trust funds, which support the Old-Age and Survivors Insurance (OASI) and Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI) programs, will be depleted in 2034. That was well within the range they’ve projected for the past two decades. Even after the combined trust funds are depleted, Social Security could still pay about three-fourths of scheduled benefits using its tax income. Likewise, the trustees estimated last year that Medicare’s Hospital Insurance (HI) trust fund could still pay 87 percent of scheduled benefits after its reserves are depleted in 2028.

Fluctuations from year to year in the trustees’ long-term estimates are normal. A variety of demographic factors (including fertility, mortality, and immigration) and economic variables (including wage growth, inflation, and interest rates) affect Social Security, and the actuaries constantly improve their methods. Those same variables, as well as the growth of health care costs, also drive the Medicare projections.

Revisions of a year or two, in either direction, therefore are neither a reason for alarm nor for celebration. In fact, the trustees caution that their projections are uncertain. For example, last year they estimated a 95 percent chance that Social Security’s trust fund reserves would be depleted between 2029 and 2045. More recently, the Congressional Budget Office estimated that exhaustion would occur in 2029. In short, all reasonable estimates show a manageable long-run challenge but not an immediate crisis.

The Medicare trustees report will include a determination of whether projected Medicare spending will exceed the target that would trigger spending reductions under the provisions of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) relating to the Independent Payment Advisory Board (IPAB). In last year's report, the trustees projected that Medicare spending for the 2017 IPAB determination year would exceed the statutory target by just 0.2 percent. If the process is triggered, IPAB is required to propose ways to trim Medicare spending by achieving savings in the payment and delivery of health care services so that it no longer exceeds the target. The board, however, is specifically prohibited from rationing health care, raising Medicare’s premiums or cost sharing, cutting benefits, or restricting eligibility.

Because the trustees' projections are based on current law, they won’t reflect the impact of bills before Congress to repeal the ACA. The repeal bills that the House passed and the Senate is now considering would move up the depletion of Medicare’s HI trust fund by two years, from 2028 to 2026. That’s because both bills would repeal a payroll tax increase on high earners and increase Medicare payments to hospitals that serve many uninsured patients. The HI trust fund is now projected to remain solvent 11 years longer than before the ACA, thanks in large part to ACA reductions in provider payment rates. (The House and Senate bills wouldn’t repeal those reductions.)

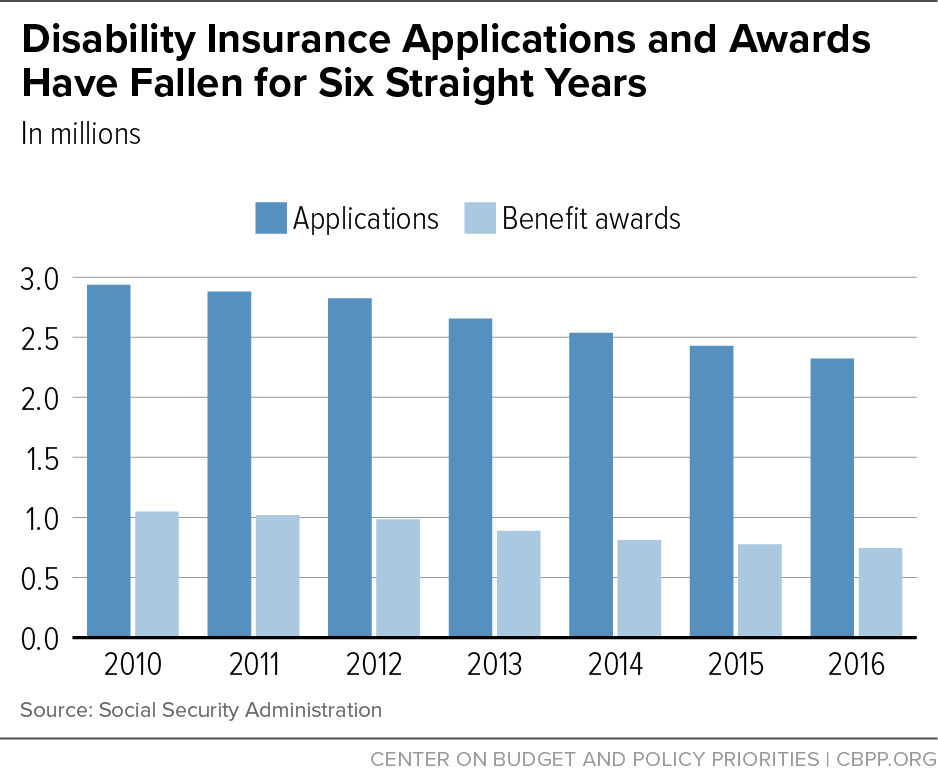

A 2015 budget deal extended the solvency of the SSDI trust fund until 2023, according to last year’s trustees report, by temporarily allocating a bigger share of the payroll tax to it as opposed to OASI. The number of SSDI applicants and beneficiaries has declined over the past several years, as demographic and economic pressures on the program have eased. (See chart.) Analysts anticipated this trend, since most of the recent growth in SSDI enrollment was due to demographic factors like the aging of the baby boom generation into its peak disability-prone years. As the boomers reach retirement, the number of workers receiving SSDI benefits has declined for three straight years. Likewise, SSDI applications (more than half of which are rejected) spiked during the aftermath of the Great Recession but have fallen every year since 2010.

Contrary to claims by Office of Management and Budget director Mick Mulvaney, the trustees have projected that the share of Americans receiving SSDI and the share of taxable payroll (the wage and self-employment income subject to Social Security taxes) spent on SSDI will remain stable in coming decades.

You can find our takes on last year’s trustees’ reports and more Social Security and Medicare analyses on our site.