BEYOND THE NUMBERS

Massachusetts Ballot Measure Would Raise Billions for Education, Infrastructure

Massachusetts voters this November will consider the Fair Share Amendment (FSA), a ballot measure that would establish an additional tax on the portion of people’s income over $1 million a year to raise revenue for stronger schools and a more efficient, safe, and reliable transportation system. It’s a good idea that, if approved, would boost Massachusetts’ position as an economic leader among states.

There’s also little evidence for opponents’ claims that outmigration or tax planning by the state’s millionaires will significantly undercut the projected billions of dollars the measure would raise for education and transportation.

Right now, Massachusetts taxes all income at the same rate, so cashiers and cooks pay the same rate as a CEO even though they have a much harder time meeting basic needs. In most states, rates rise with income, but Massachusetts’ constitution includes a provision barring such a structure. The FSA would amend the constitution to establish a higher rate on the portion of income over $1 million, bringing the state more in line with most states’ graduated rate structures. (Income under $1 million would be unaffected, including the first $1 million earned by people with income exceeding that.)

In 2021 the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy estimated that the measure would raise about $2.7 billion in its first year. The state estimated $2 billion in 2015, early in the measure’s journey to potential enactment.

Massachusetts voters can feel secure that the new tax on high-income households would form a consistent revenue stream to fund investments that improve the quality of life for all residents. Evidence from other states with higher tax rates on wealthy households suggest that this portion of the tax base is reliable — in other words, that tax changes aren’t a major factor in determining whether wealthy residents move.

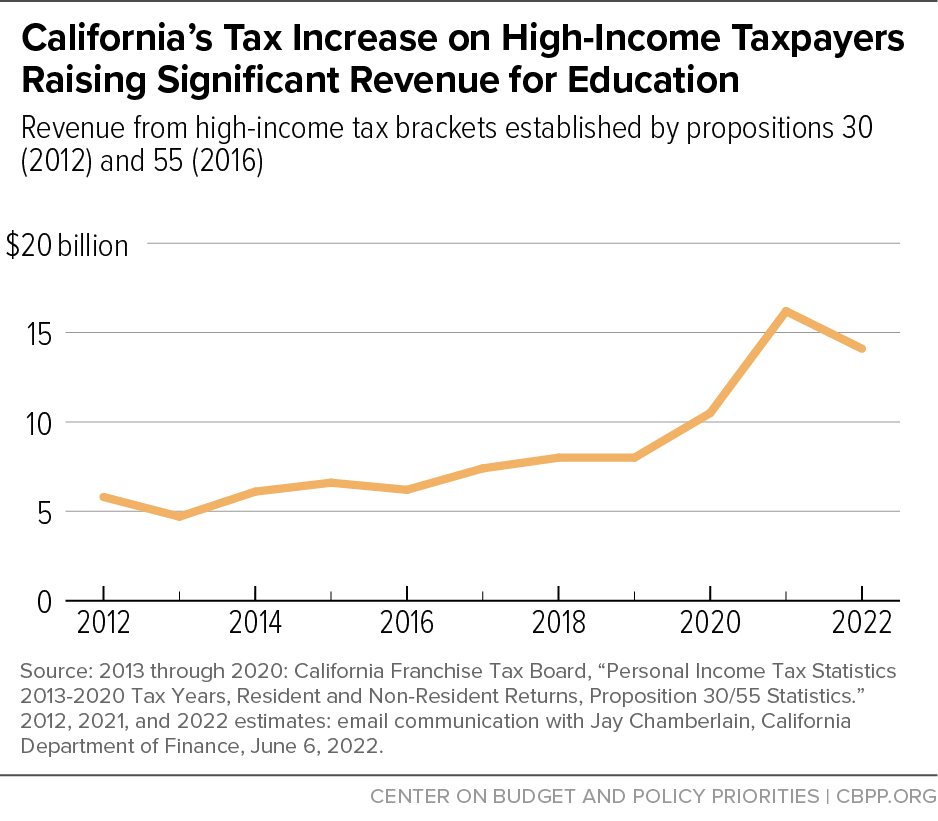

Take for example, California’s Proposition 30, which voters approved in November 2012 to establish three additional high-income tax brackets, with rates 1, 2, and 3 percentage points higher than the previous top rate of 9.3 percent. Married couples with incomes above $1 million saw their top rate rise from 10.3 percent to 13.3 percent (previously they were liable for an additional 1 percent surcharge).

The revenue raised by Proposition 30 and its voter-approved extension, Proposition 55, has far exceeded expectations. California originally estimated collections of $5 billion a year. But as the graph below shows, yields have risen steadily from the $5.8 billion collected in 2012. The only exceptions are a brief drop to $4.7 billion in 2013 — likely because an expiring federal income tax cut provided an incentive for taxpayers to accelerate stock sales that would have been made in 2013 into 2012 — and the projections for 2022, down from last year as the stock market fell in the uneven pandemic recovery. Still, at $14.1 billion, revenues received from the tax remain high and have risen steadily over time.

California is also instructive in that, since 2011 (the period for which the IRS has complete data), it has had the country’s lowest average annual outmigration rate of people earning more than $200,000, despite having the highest top income tax rate (at 13.3 percent). Massachusetts’ top rate under the FSA, meanwhile, would be a lower 9 percent (up from 5 percent, making the increase similar to Proposition 30’s). And it has a lower outmigration rate among people with incomes above $200,000 than neighboring New Hampshire, which has no state income tax.

Lastly, claims that Massachusetts would lose a large share of the ballot measure’s expected revenue to new tax avoidance are overblown. A recent analysis — which notably acknowledges that erosion of FSA revenue from out-movement of millionaires would be small — estimates that fully 30 percent of the revenue could be lost due to affected taxpayers taking steps to report less income. Such a prediction is simply not credible. It largely rests on a statistical analysis of California’s Proposition 30 whose conclusion is belied by the actual revenue data just presented.

In reality, while taxpayers faced with a significant rate increase can accelerate the realization of income into the year before the tax increase takes effect or delay it into later years (for example, by speeding up or delaying the sale of stock), relatively few can delay the reporting of income indefinitely. The few who can already have a major incentive to do so because of the much higher tax rates under the federal income tax; it’s unlikely that a 4 percentage point state tax rate increase would be a new tipping point for more than a relative handful. In other words, most of this time-shifted income will eventually be subject to the tax. The few filers who can delay paying their tax are probably already doing so.

If Massachusetts enacts the Fair Share Amendment it can expect to raise nearly all the revenue it estimated, or quite possibly even more. In a state where some people take in enormous incomes and others struggle to put food on the table, Massachusetts would do well to adopt this measure and use the revenue to provide all children in the state with a high-quality education and to rebuild its transportation systems for the 21st century.