BEYOND THE NUMBERS

Most Social Security Disability Insurance (DI) beneficiaries whose benefits stop because their medical condition has improved have little capacity for substantial and sustained work, a new study finds. It’s further evidence that DI is hard to get on and stay on; benefits go only to people with very severe impairments who have lost most of their ability to work.

Workers who meet DI’s strict eligibility criteria can’t count on receiving benefits for life. The Social Security Administration (SSA) regularly reviews their medical condition and eligibility for benefits. In most cases, reviews take place every three years — if lawmakers provide enough funding.

The researchers tracked more than 2 million DI beneficiaries targeted by SSA for a full medical follow-up during a continuing disability review (CDR) between 1998 and 2008. (SSA winnowed those cases from the far larger number of reviews conducted by mail.) Among their findings:

- Overall, 5.7 percent of beneficiaries who got a full medical review lost DI as a result. Though they were severely disabled when they first qualified for DI, their condition had improved in the meantime.

- Younger beneficiaries were much likelier to lose their benefits. (DI’s eligibility criteria are also tougher for young applicants.)

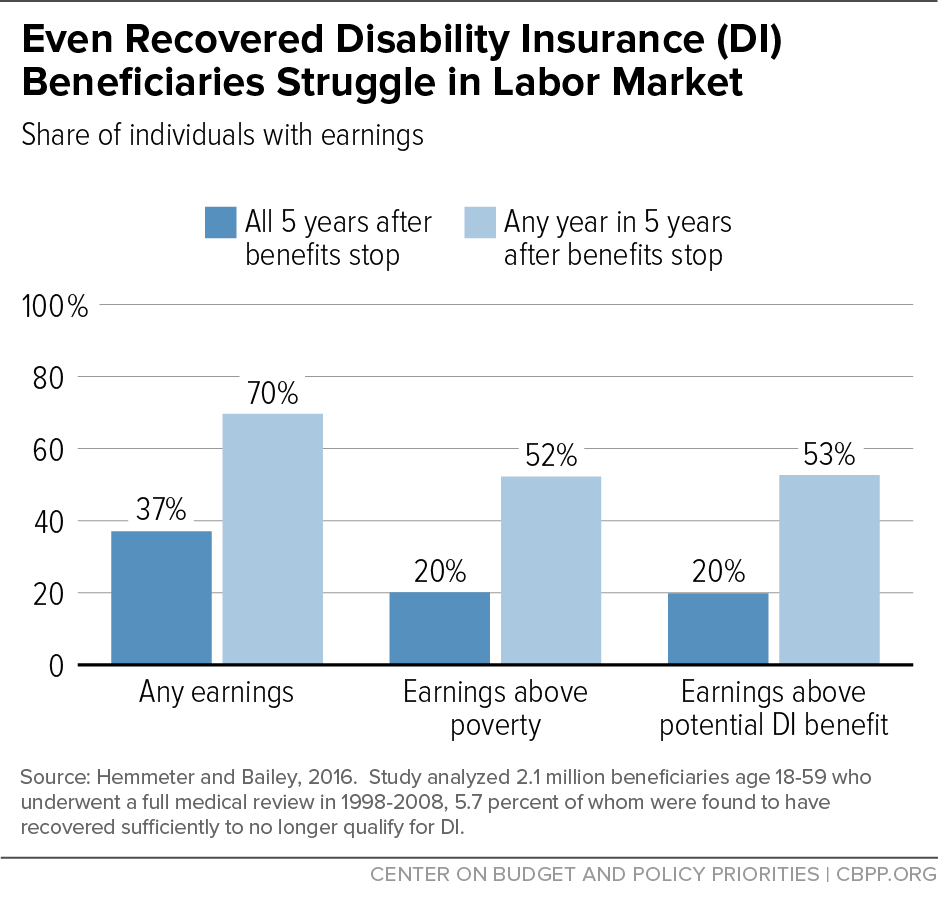

- Beneficiaries who lost their benefits — by definition, the healthiest DI recipients, with a strong incentive to work — typically managed to go back to work, but worked only sporadically and at modest earnings. Seventy percent had earnings in at least one of the five years after their benefits stopped, but only 37 percent worked in all five years. (See graph.) And even fewer earned enough, by reasonable measures, to support themselves. Only half earned more than the poverty level in any year; only 20 percent earned above poverty in all five years. Similarly small fractions earned more than the DI benefit that they lost — evidence that, financially, most were worse off.

Beneficiaries who have recovered, according to DI’s criteria, often continue to have serious health problems. Other research shows that many people who lose DI benefits — at least one-fifth, in one study — eventually return to the rolls as their medical condition and work capacity deteriorate again.

These sobering outcomes support an expert panel’s recommendation that Congress extend DI beneficiaries’ eligibility for rehabilitation and employment support services for a year after their benefits end. The panel also urged SSA to communicate work expectations clearly for beneficiaries most likely to recover so they’re not caught off-guard by their continuing disability review.