BEYOND THE NUMBERS

As policymakers consider what could be the last COVID-19 relief package this year, they should respond to the alarming rise in the number of children who aren’t getting enough to eat by increasing SNAP (food stamp) benefits, which would minimize COVID-19’s lasting impact on a generation of children.

Policymakers, including Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell and Senate Democrats, have called for policies that support children in the next package. That’s wise, because many families with children, particularly low-income families, already struggled with food insecurity and other hardship before the pandemic, and they’ve been hit especially hard by the crisis. With schools closed, many children, particularly low-income children, have missed out on educational instruction and other supports with potentially lasting consequences; many families of low-income children who normally eat free- or reduced-price meals at school also suddenly had to provide those meals just as they were losing jobs and other income.

Compared to childless families, families with children were likelier to lose employment income — over half of families with children report such losses — and likelier to be behind on rent or mortgage payments. Rising food costs are also likely further straining parents’ budgets.

These factors have driven shocking increases in food insecurity affecting children, with over one-quarter of households with children reporting food insecurity in recent weeks. Those levels, which have been consistent across various surveys, have likely at least doubled from pre-COVID-19 levels.

Families of color, which already had elevated rates of food insecurity due to longstanding inequities in income, wealth, and food access, are now experiencing even greater food hardship, with recent data showing that close to two-fifths of Black and Hispanic households with children experienced food insecurity in recent weeks.

Some data suggest that household food insecurity may have fallen somewhat from its peak (in one survey, from 35 percent in April to 28 percent in early June among households with children), but it remains significantly higher than pre-crisis rates. These drops may be due in part to low-income families receiving some temporary increases (from the Families First Coronavirus Response Act of March) in SNAP, which before the pandemic served about 17 million children.

That emergency aid likely helped many families afford food, but it’s temporary and may expire when federal or state emergencies end, which may be well before food insecurity improves. It also leaves out the poorest 40 percent of SNAP households with the lowest incomes, including at least 5 million children. Pandemic EBT (P-EBT), a program (also from Families First) to provide benefits to replace the value of those lost meals during school closures for children receiving free- and reduced-price meals, may also have helped alleviate short-term hardship, but it is also temporary (only providing assistance through the school year) and cannot fully offset families’ other lost income.

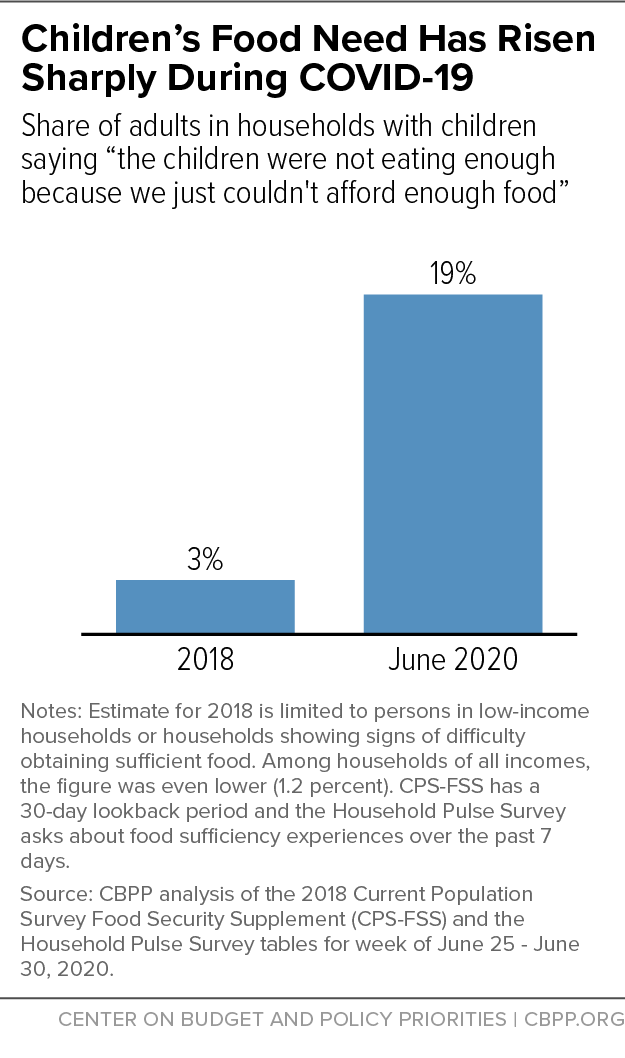

High rates of food insecurity among families with children don’t always mean that children go hungry. Parents and other caretakers try to shield their children from food insecurity, often eating less or skipping meals themselves so that their children still have enough to eat; that’s why food insecurity among children is rarer than food insecurity among households with children. That’s also why data from the Census Bureau’s Household Pulse Survey from late June showing that 18.8 percent of adults in households with children report that children in their household sometimes or often didn’t eat enough in the past week because their families couldn’t afford food is deeply concerning. Rates are even higher among households of color, with over one-quarter of Black and Hispanic households reporting that children weren’t eating enough, research from the Hamilton Project shows.

That’s a substantial rise from previous levels; in December 2018, only about 3 percent of adults in households with children reported that children were sometimes or often not eating enough. Moreover, the 2018 survey asked households about food problems in the last month; if it had asked about the last week, as the Pulse survey does, the 2018 result would have been even smaller and the increase since 2018 even bigger.

Food insecurity among children can have negative consequences far into their futures. Nutrition in infancy and early childhood is linked with outcomes that can affect individuals throughout their lifetime, a large body of research finds; for example, early iron deficiency is linked with long-term neurological damage. School-aged children who don’t get enough to eat may have more difficulty learning in school, which can translate to worse longer-term outcomes, such as lower high school completion rates and lower earnings potential. Children of all ages exposed to food insecurity are also at higher risk of negative health outcomes, such as higher rates of asthma and anemia.

Ensuring that children get enough to eat can help improve those outcomes. Studies of access to SNAP in the 1960s and 1970s find that such access in early childhood had long-term impacts, contributing to better health and other measures of well-being. Children receiving benefits that cover less of their food costs are likelier to have worse health outcomes, which underscores the importance of ensuring that SNAP benefits cover costs.

The high food insecurity figures and their potential consequences — and the chance that they will continue for months — make the case that policymakers should provide additional, lasting support. Forecasts suggest that economic conditions such as unemployment may be elevated at least through 2021.

Given the historic relationship between food insecurity and unemployment, food insecurity will also likely remain high in the months to come, with many families struggling to find adequate work and pay bills. One key first step to addressing food insecurity is boosting SNAP. Increasing SNAP benefits for all households by raising SNAP’s maximum benefit by 15 percent and maintaining that increase as long as the economy remains weak would help families put food on the table and help stimulate the economy by enabling families to buy more food in local stores.