off the charts

POLICY INSIGHT

BEYOND THE NUMBERS

BEYOND THE NUMBERS

Social Security is one of the nation’s most successful, effective, and popular programs. Most Americans, both young and old, value Social Security and say they don’t mind paying for it. Indeed, young people are tomorrow’s retirees, just as retirees are yesterday’s young people.

But commentators sometimes misrepresent Social Security as just a “transfer from the young to the old,” or exaggerate the challenges it faces.

- Social Security is important to young people. Many young people benefit from Social Security right now: 1 in 5 beneficiaries is younger than retirement age largely due to disability or the death of a parent.

- Social Security faces future deficits, but it’s also built a surplus. Social Security’s costs will grow as the large baby boom generation moves further into retirement. But it has a large surplus to help pay those costs. Since the mid-1980s, Social Security has collected more in taxes and other income each year than it pays out in benefits. It has amassed combined trust funds of $2.8 trillion, invested in interest-bearing Treasury securities, which — along with current tax revenues — will keep the program solvent through 2034.

- Social Security will exist for young Americans. Even in the implausible event that policymakers do nothing, Social Security could still pay three-fourths of scheduled benefits after 2034, relying on current workers’ contributions to Social Security, according to the Social Security trustees’ 2015 report. Alarmists who claim that Social Security won’t be around when today’s young workers retire either misunderstand or misrepresent the projections.

- Social Security’s long-term gap must be understood in context. Looking at future spending on Social Security and Medicare is instructive only when compared with the size of the future economy. The long-term gap between Social Security’s projected income and promised benefits is just under 1 percent of the economy over the next 75 years, the trustees estimate.

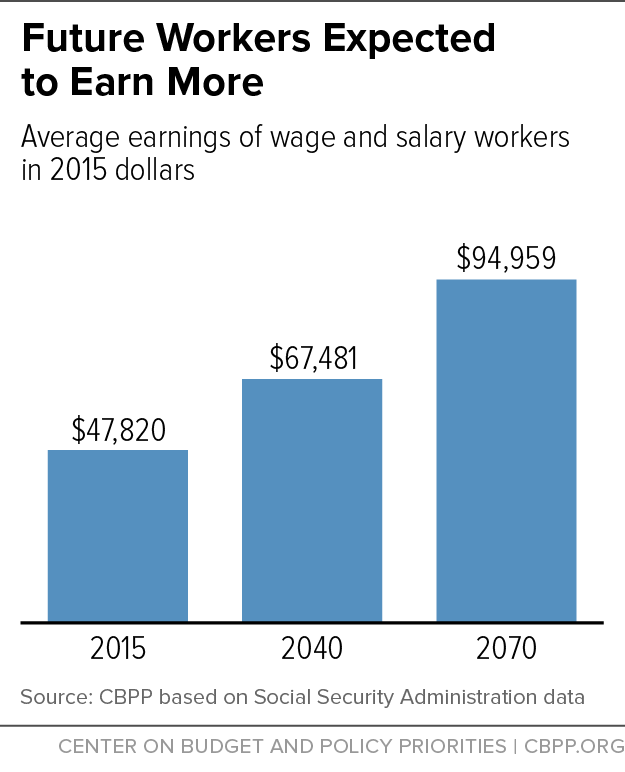

- Future wage growth dwarfs potential payroll tax increases. If Congress restored Social Security’s long-term balance solely by raising payroll tax rates now — without touching the taxable maximum benefit formula or the cap on taxable earnings — workers and employers would each pay only 1.31 percentage points more of wages toward Social Security. If policymakers delayed for another decade or two, that rate would be higher, but future workers will be more prosperous than today’s, the trustees project. Under the trustees’ assumptions, the average worker will be about 40 percent better off — in real terms — in 2040 than in 2015, and twice as well off by 2070 (see chart). It’s appropriate to devote a small portion of those gains to Social Security, while still leaving future workers with much higher take-home pay.

- Seniors have earned their benefits and many don’t have much else to live on. For more than one-third of retirement beneficiaries, Social Security constitutes at least 90 percent of income. Half of people aged 65 to 74 have no retirement savings. Without Social Security, almost half of the elderly would live in poverty.

A mix of tax increases and modest benefit reductions — carefully crafted to shield the neediest recipients and give ample notice to all participants — would put Social Security on a sound financial footing indefinitely.

Topics:

Stay up to date

Receive the latest news and reports from the Center