- Home

- States Should Target Senior Tax Breaks O...

States Should Target Senior Tax Breaks Only to Those Who Need Them, Free up Funds for Investments

By 2030, 1 in 5 Americans will be over 65, and this growing elderly population will stretch state budgets thin not just with their health care and other needs, but with the expensive tax breaks that every state provides seniors.

By 2030, 1 in 5 Americans will be over 65,[1] and this growing elderly population will stretch state budgets thin not just with their health care and other needs, but with the expensive tax breaks that every state provides seniors. These breaks cost states 7 percent of state income taxes on average in 2013, a figure that will only rise.[2] Based on growth in population and personal income, the cost of these tax breaks is now approximately $27 billion a year and will more than double by 2030.[3] A large share of these costly breaks go to higher-income seniors who need them the least. States should reduce this expense by better targeting relief to seniors with low incomes.

The senior tax breaks are poorly targeted because of their design: most states provide them regardless of the recipient’s income or savings. In particular, exemptions for retirement income such as pensions benefit those higher up the income scale more. As a result, these state policies favor those fortunate enough to receive pensions or annuities — either through a defined benefit plan or a contribution-based plan like a 401(k) — and whose jobs pay enough for them to save for retirement. They also favor those who do not need to continue to work past the traditional retirement age in order to support themselves and their families. These state tax preferences are widespread:

- Some 28 states and the District of Columbia completely exempt Social Security income from their income tax, regardless of the tax filer’s income and wealth;

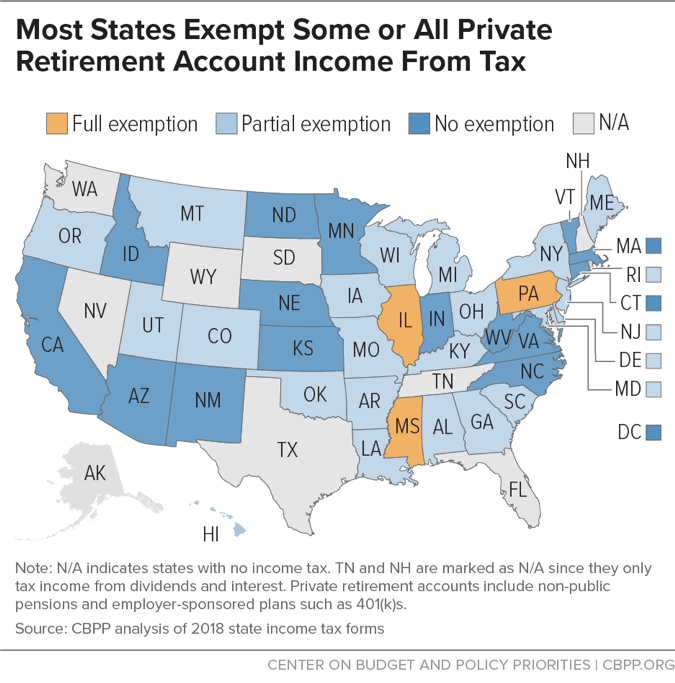

- 26 states either fully or partially exempt income from non-governmental private retirement accounts such as pensions from taxation;

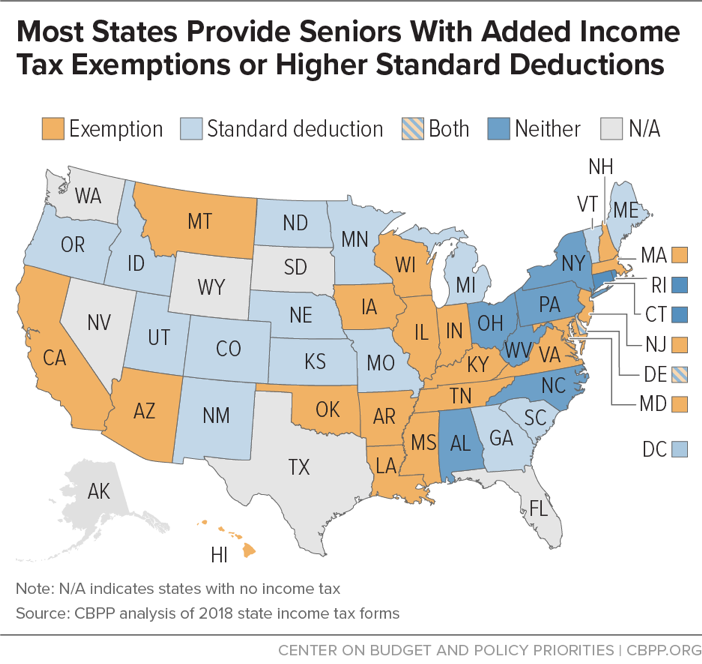

- All but six states give additional personal income tax exemptions, standard deductions, or credits based on age; and

- Many states assist local governments with the costs of age-based property tax reduction programs; 21 states offer homestead exemptions (which exempt a flat amount of home value from property tax) or credits targeted to the elderly. An additional five states give local governments the option of providing these exemptions.

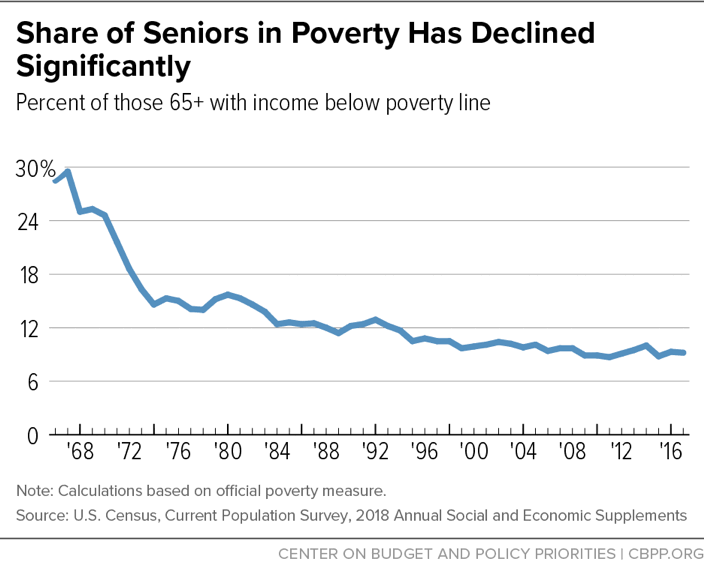

One justification for these tax breaks is that seniors live on low, sometimes fixed incomes, while the costs that they face, especially for health care and housing, continue to grow. But states first established many of these preferences decades ago, when poverty among the U.S. elderly was much more widespread. In 1970, some 25 percent of this over-65 population had below-poverty income, hence states’ attempts to relieve their tax obligations. Since then, Social Security and Supplemental Security Income (SSI) coverage has expanded, and today, only 9 percent of the elderly are poor.[4] But the distribution of income among seniors has become more lopsided. Inequality among seniors in the United States is higher than in any Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development country other than Chile and Mexico and is growing with each generation.[5]

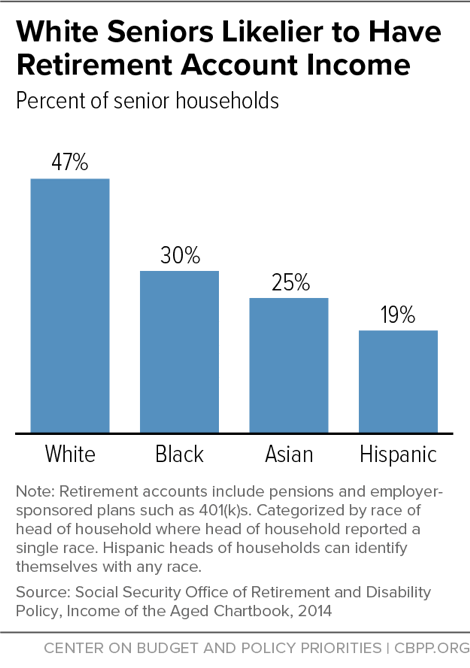

These tax breaks reinforce unequal distributions of income and wealth, with some groups facing particularly high barriers to accumulating savings and other assets. For example, many Black and Hispanic families have faced long-standing employment and housing discrimination that have made it difficult to build savings for each generation and invest in the future of the next. As a result, such families’ wealth generally is far less than that of white families.[6] People of color are also less likely to be covered by a defined benefit pension plan and are much less likely to have retirement savings than white households of the same age and income.[7] As a result, many longstanding state tax preferences for seniors now benefit taxpayers with much better ability to pay taxes than lower-income households.

To raise the revenue needed to support services for seniors and others now and in the future, states can instead target senior tax breaks to those who need them most, by means-testing and/or raising age eligibility of tax exemptions for seniors and retirees, expanding state Earned Income Tax Credits to seniors, providing property tax relief through “circuit-breakers” (which base payment amounts on affordability), and making state tax systems less upside-down in general.

It’s crucial that states consider revenue challenges along with the spending challenges that the aging of the population will bring. And they should do so now, before the full impact of baby-boom retirements hits and the tax preferences’ cost begins to rise rapidly. (We describe political considerations behind taking such steps in the box, “Designing Change to Increase Chances of Adoption.”)

Financial Outlook Improved for Many in Aging Population, Others Face Barriers

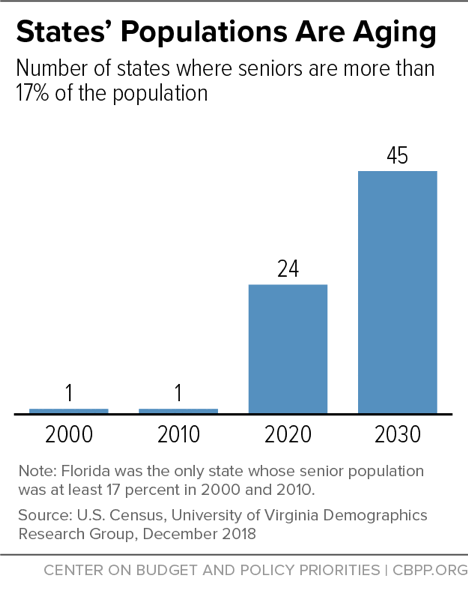

The U.S. population is aging as medical advances have increased life expectancy and as baby boomers move beyond middle age. Nationally, the elderly proportion of the population is projected to grow from 16 percent in 2017 to 19 percent by 2030, likely affecting all states. At the time of the last decennial census in 2010, elderly residents made up more than 17 percent of the total population in only one state (Florida); by 2030, all but five states and the District of Columbia will be in this category. (See Figure 1 and Appendix Table 1.)

The last four decades have seen a significant improvement in U.S. senior citizens’ financial well-being. In the 1960s and 1970s, when many states adopted tax preferences for seniors, elder poverty was a much larger problem. In 1970, more than 1 in 4 elderly Americans had below-poverty incomes; that’s down to less than 1 in 10 today.[8] (See Figure 2.) Because age is no longer so strongly correlated with poverty, states should target tax relief by income.

While a smaller share of seniors live in poverty than in the past, many still struggle to get by. Seniors who have spent their lives working hard, raising a family, and contributing to their communities deserve time to relax with family and friends and focus on interests other than work such as volunteering, sports, creating, or traveling. But this ideal is not within the reach of many.

Most workers are left largely on their own to accumulate savings and assets to fund their retirement beyond what Social Security will provide. The share of private-sector jobs with retirement accounts such as defined benefit pensions or employer-sponsored plans such as 401(k)s has declined substantially since at least the 1980s,[9] and individuals with retirement accounts are more likely to have moderate to high incomes. Taxpayers with income over $75,000 receive some two-thirds of federally taxable retirement account income.[10] In addition, workers of color are much less likely have a job that provides retirement benefits — either pensions or 401(k)s. Only 54 percent of Black and Asian workers and 38 percent of Latinx workers are in jobs with a retirement plan, compared to 62 percent of white workers.[11] Some 47 percent of white senior households receive some retirement account income, compared to 30 percent or fewer of senior households of color.[12] (See Figure 3.)

Today’s retirees spent their working years in a time of rapidly growing income and wealth inequality. With the lion’s share of income going to the minority of people at the top, low- and moderate-income families face barriers to setting aside a nest egg for retirement.

Some groups face particularly high barriers to accumulating savings and other assets. For example, Black and Hispanic families have faced long-standing employment and housing discrimination that have made it difficult for each generation to build savings and invest in the future of the next.[13] As a result, the median net worth of white families is ten times that of Black families and eight times that of Latinx families.[14]

Younger, Wealthier Seniors Get State Tax Breaks Better Targeted Elsewhere

Lower poverty rates and improved health among seniors raise questions about whether states should not only implement means-testing for their senior tax preferences, but also change the age of eligibility, which most states set at 60 or 65. Some 8.2 percent of Americans age 65 to 74 are poor, compared to 10.6 percent for those 75 and over. While people are living longer and older Americans are healthier and more active than in the past — the share of Americans age 65 and older reporting excellent or very good health increased from 42 percent to 48 percent between 2000 and 2014, for example[15] — health declines the longer people live. “Poor physical functioning is being increasingly compressed in the period just before death,” according to a 2013 paper from the National Bureau of Economic Research.[16]

Giving additional tax breaks to younger, wealthier seniors who don’t need them strains state budgets, especially given the other programs and services that state budgets must fund, including for the elderly. For example, states provide on average 47 percent of the funding for the Medicaid program, which pays for the vast majority of long-term care in this country and bears a portion of the prescription drug costs for low-income elderly people. States also will have to finance retirement accounts and health care for a growing number of retired state employees. In addition, states and localities provide public amenities like transit systems, libraries, and parks to make a secure, comfortable retirement more widely available. Elderly-related costs borne by state and local governments for other programs ranging from special transportation to social services will also increase.

Designing Change to Improve Chances of Adoption

A key question is whether it is politically possible to modify senior preferences in ways that this report suggests. Policymakers are aware that older Americans vote in disproportionate numbers, and that they are vocal in making their needs known. Nevertheless, it will become increasingly difficult for states to meet those needs if they fail to modify some of these preferences before more and more baby boomers become qualified to take advantage of them, further draining state budgets. Ways to improve the political chances of enacting needed changes include:

Making changes in senior preferences part of a larger tax reform package, as the District of Columbia did when it eliminated its tax exemption for public and private pension payments in 2014. Such reform packages may include other changes that seniors view favorably, including exempting food or pharmaceuticals from sales tax or enacting an income-targeted credit to offset the sales tax on those items, or increasing another tax to fund specific services important to seniors. In addition, if states also change tax preferences for some other groups, seniors may feel less singled out.

Meeting with organizations representing seniors in the state to discuss their priorities. They may consider some things more important than preferences for higher-income seniors and may be open to using the revenue from curtailing the preferences, or other revenue, to fulfill those priorities.

When proposing a change from a non-targeted senior preference to a targeted one, it may be possible to set the income ceiling for the preference at a level that will encompass between a third and a half of all seniors in the state. This could help deflect opposition.

It might be possible to make the preference more generous for the lowest-income seniors while eliminating it for seniors at higher incomes. This could garner support for the change.

Many people at age 65 today do not consider themselves old, and few are poor. Poverty is higher at age 75 and higher still at age 85. It may be possible to re-target the senior preferences to an older cohort, rather than using age 65 as the qualifying age. In combination with some of the other strategies above, this could improve the chances of support for the change.

Retaining tax preferences for those already receiving them — grandfathering — could make the changes more acceptable because no one would lose a benefit that they are already receiving. In addition, phasing in the change rather than eliminating a benefit all at once could make it more palatable.

Existing Senior Tax Preferences

States provide tax reductions for seniors by fully or partially exempting Social Security and income from retirement accounts such as pensions from state income tax; offering income tax exemptions, standard deductions, or credits based on age; and providing age-based property tax reduction programs. In every state with an income tax, seniors pay less on average than other taxpayers with equivalent incomes, though this varies significantly by state. Table 1 shows the percentage that the income tax liability of elderly taxpayers is of that of non-elderly taxpayers with the same amount of income.[17] For example, the income tax liability of the elderly taxpayers in Pennsylvania is half of that of otherwise comparable non-elderly taxpayers.

| TABLE 1 | |

|---|---|

| Elderly Income Tax Liability as Percent of Non-Elderly Liability in 2013 | |

| State | Percent |

| Georgia | 41.8% |

| Michigan | 43.6% |

| Mississippi | 47.5% |

| South Carolina | 48.7% |

| Kentucky | 49.9% |

| Pennsylvania | 49.9% |

| Illinois | 55.6% |

| Delaware | 56.8% |

| West Virginia | 57.4% |

| Indiana | 60.5% |

| Iowa | 60.6% |

| Idaho | 61.7% |

| Oklahoma | 62.3% |

| Arkansas | 62.5% |

| Louisiana | 63.9% |

| Wisconsin | 64.1% |

| Ohio | 65.6% |

| Oregon | 65.6% |

| Alabama | 66.0% |

| North Carolina | 66.2% |

| Virginia | 66.3% |

| New York | 66.7% |

| Colorado | 66.8% |

| Arizona | 67.4% |

| Maine | 68.4% |

| Maryland | 69.1% |

| Missouri | 69.7% |

| Hawaii | 73.3% |

| New Jersey | 73.5% |

| Massachusetts | 76.3% |

| Kansas | 77.3% |

| Utah | 80.6% |

| Montana | 81.5% |

| California | 82.4% |

| Connecticut | 82.5% |

| Minnesota | 83.2% |

| New Mexico | 84.6% |

| Nebraska | 86.7% |

| Vermont | 86.8% |

| District of Columbia | 88.3% |

| North Dakota | 88.4% |

| Rhode Island | 89.8% |

Note: Excludes states without an income tax. The percentage equals the total amount of income taxes paid by senior-headed households in the state divided by the amount of income taxes these households would owe if headed by a taxpayer under 65. See box, “Methodology: Estimating Size and Cost of Senior Tax Breaks,” for more detail.

Source: Ben Brewer, Karen Smith Conway, and Jonathan C. Rork, “Protecting the Vulnerable or Ripe for Reform, State Income Tax Breaks for the Elderly: Then and Now,” Public Finance Review, Vol. 45, No. 4, 2017, pp. 564-594.

In six states – Georgia, Michigan, Mississippi, South Carolina, Kentucky, and Pennsylvania – senior taxes are less than half of what taxpayers under 65 with similar incomes pay. In only nine states with broad-based income taxes[18] and the District of Columbia, meanwhile, are senior taxes at least 80 percent of the amount owed by taxpayers under 65.

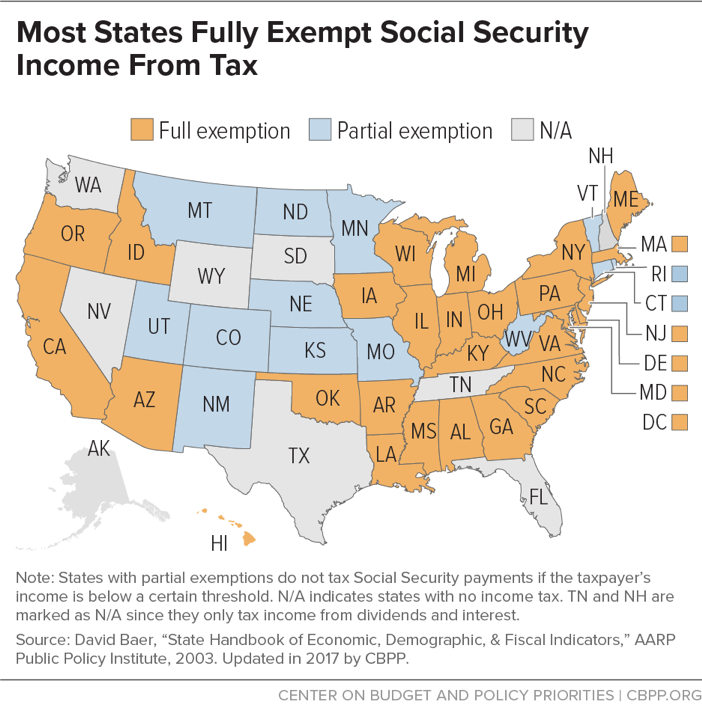

Social Security income. Social Security payments receive some form of special treatment in every state with a personal income tax. Some 28 states and the District of Columbia fully exempt such payments from their income tax regardless of the taxpayer’s income. (See Figure 4 and Table 3.)

This is a vestige of the full exemptions that Social Security income enjoyed from federal and state taxation until the mid-1980s. At that time, as part of an initiative to restore Social Security’s finances and due to many seniors’ improved economic status, the federal government began to tax a portion of recipients’ benefits above a specified income level. Under current federal law, Social Security payments are fully exempt from federal income tax for single taxpayers with incomes below $25,000 and for married taxpayers with incomes below $32,000.[19] The federal government taxes 50 percent of the benefits of individuals with incomes between $25,000 and $34,000 and couples with incomes between $32,000 and $44,000. It taxes 85 percent of the benefits for individuals with incomes over $34,000 and couples with incomes over $44,000.

Most states failed to change their treatment of Social Security income when the federal government did, and maintained their full exemption. Only six states — Minnesota, New Mexico, North Dakota, Utah, Vermont, and West Virginia — currently follow the federal provisions.[20] Seven states — Colorado, Connecticut, Kansas, Missouri, Montana, Nebraska, and Rhode Island — tax some Social Security income using a different formula.

Methodology: Estimating Size and Cost of Senior Tax Breaks

The estimates of tax liability of senior households compared to tax liability of households under 65 were calculated in a paper by Brewer, Conway, and Rork (see sources below) using the sample of households for each state in the U.S. Census’ American Community Survey.

First, the state income tax owed by households headed by seniors in 2013 was estimated using the TAXSIM model maintained by the National Bureau of Economic Research, which includes tax provisions for each of the 50 states.

Then the tax liabilities of these same households were computed again, but the age of the head of household was assumed to be under 65 and the classification of income sources was changed from pension and other age-related income to other income, without changing the amount of income for each household. This allowed a comparison of the effect of age alone on the amount of income tax owed in each state.

Table 1 compares the total amount owed by senior households to the total amount owed if these households were headed by someone under 65 by dividing the total owed by senior households by the total owed by the equivalent non-senior households. The resulting percentage shows the magnitude of the age-related tax breaks in each state.

Table 2 shows the percentage reduction in income tax revenue due to tax breaks for those 65 and over. First, the difference between the tax owed by each senior-headed household and the equivalent household headed by someone under 65 is calculated. The sum of these differences for each state is the total revenue lost due to senior tax breaks. This total is divided by total income tax collections to determine the percentage reduction in income taxes. Because this analysis was based on 2013 taxes, the resulting revenue loss was adjusted for growth in income tax collections and number of seniors between 2013 and 2017 to estimate the 2017 dollar loss. This estimate provides an estimate of the current magnitude of the loss but does not account for tax policy changes between 2013 and 2017.

Source: Senior tax liability as a share of tax liability for non-seniors and percent loss: Ben Brewer, Karen Smith Conway, and Jonathan C. Rork, “Protecting the Vulnerable or Ripe for Reform, State Income Tax Breaks for the Elderly: Then and Now,” Public Finance Review, Vol. 45, No. 4, 2017, 564-594; 2017 dollar loss: CBPP calculations of Brewer, Conway, Rork data and Census Bureau data

Pensions and other retirement income. As people near and pass retirement age, their income sources change significantly. For those age 55 to 65, wages and salaries make up over three-fourths of their income. For those 65 and over, wage and salary income declines to 36 percent of income and Social Security and income from retirement accounts make up half of their income.[21] Social Security alone accounts for one-third of the income of people 65 and older.[22]

There are two major types of employment-based pension plans: defined benefit plans and defined contribution plans.

Under defined benefit plans, employers promise a specific regular payment to the employee in retirement. The employer contributes the amount necessary over the work life of the employee to pay the benefits after retirement. These contributions are tax deductible for the employer at the time they are made. And for federal tax purposes, the pension payments that employees receive in retirement are taxable.

Under defined contribution plans, the employee has access to a savings account that is funded through employee contributions and in many cases also through contributions by an employer. The contributions to the plans are usually made with pre-tax dollars; neither the employee nor the employer pays tax on the funds contributed. The income the plan earns also is not taxable while it remains in the account. Withdrawals from defined contribution plans are fully taxable for federal tax purposes. Traditional IRAs that allow tax-free deposits operate in the same manner as defined-contribution pension plans, as do various plans for self-employed individuals.[23]

These types of plans are called tax-deferred, because the tax on the contributions and earnings is not payable until funds are withdrawn. The tax deferral provides a benefit because the employee can accumulate more funds in the account than if the contributions and earnings were taxed annually. In addition, most people have lower income after retirement than they did while they were working and may be in a lower federal tax bracket at the time they withdraw the funds and thus pay less tax on the funds when they are withdrawn.

The federal tax treatment of pension contributions provides a significant benefit to taxpayers and is intended as an incentive to encourage retirement savings. It makes little sense for states to provide still more generous treatment of retirement income, on top of the federal tax benefits. But a number of states exempt some or all retirement account income from tax — both when it is deposited and when it is withdrawn.

All except seven states plus the District of Columbia with an income tax exempt some or all retirement account income for former government employees, which we refer to as public retirement account income, from their tax.[24] An argument could be made to treat public and private retirement account income somewhat differently, as some states do, and to exempt some public retirement account income, since it is the state or localities themselves that make these payments. Lower taxes may have been a substitute for higher wages in the past, for example. But more than half the states also extend the preferential treatment to private retirement account income. (See Figure 5 and Appendix Table 3.)

Three states — Illinois, Mississippi, and Pennsylvania — exclude all private and public retirement account income from taxable income. Other states only partially tax income from retirement accounts from private jobs. In states with partial exemptions, the amount exempted varies widely but is substantial. Sixteen states — Arkansas, Colorado, Delaware, Georgia, Iowa, Kentucky, Louisiana, Maine, Maryland, Michigan, Missouri, New Jersey, New York, Oklahoma, Rhode Island, and South Carolina — exempt more than $5,000 of public and/or private retirement account income. In most states these exemptions are available to taxpayers without regard to ability to pay. Only seven states — Missouri, Montana, New Jersey, Ohio, Oregon, Utah, and Wisconsin — limit these exemptions to taxpayers with income below specified levels.

Other income tax preferences. Additional personal exemptions or a higher standard deduction based on age are other common forms of special tax treatment. All but six states with an income tax offer an expanded exemption or credit based on age.[25] (See Figure 6 and Appendix Table 4.) The most common forms are an additional personal exemption or credit or a higher standard deduction for taxpayers over 65. The amounts of the added exemptions average approximately $1,200 for one taxpayer and $2,400 for two taxpayers. The exemptions generally are not limited to low-income taxpayers. Most states that offer higher standard deductions for those over 65 use the federal definition of taxable income, which reflects the application of a standard deduction that is $1,600 higher for single taxpayers over 65, and $2,600 higher for joint returns.

These design choices affect whether low- or moderate-income taxpayers are most likely to benefit. Because the standard deduction does not benefit those who itemize their deductions — generally higher-income taxpayers — the higher standard deduction is more targeted to lower- and middle-income taxpayers than are the additional personal exemptions. Other states offer credits to seniors ranging from $15 to $236. Of the three main types of senior tax breaks, added exemptions or standard deductions provide a proportionately greater benefit to low-income taxpayers than the exemptions for retirement income or Social Security, but they are generally smaller.[26]

A few states offer substantial exemptions of certain types of income to seniors, usually on top of the exemptions or credits above. For example, Michigan exempts $11,495 (for single filers) and $22,991 (for joint filers) in interest, dividends, and capital gains income for seniors over 73. Virginia exempts $12,000 of income from any source for taxpayers 80 and older. Similarly, West Virginia exempts up to $8,000 in income for taxpayers 65 and older, without any income limit on who can use the exemption.

Some states also offer credits that equal a portion of the means-tested federal elderly tax credit, which is only available to low-income taxpayers who receive little or no income from Social Security.[27]

Property tax preferences. Separate from income tax preferences, many states offer property tax preferences for seniors. Property tax reductions for seniors often take the form of homestead exemptions or credits that reduce the amount of property taxes owed. While the property tax is primarily a local tax, homestead exemptions can have a significant impact on state budgets. In some cases, states provide aid payments to local governments to compensate for the costs of the property tax exemptions. Even in states without these aid payments, the erosion of the local property tax base puts pressure on state governments to fill in the gap and assist localities in funding schools and other important local services.

All but 13 states offer some form of homestead exemption or credit program. (See Appendix Table 5.) Of these, 20 offer programs targeted to seniors. Of the 20, eight have senior-only programs while the others offer additional, more generous homestead exemptions or credits to seniors. Some states limit these programs to taxpayers with incomes below a specific level but more often they open them to all taxpayers regardless of income.

One way to provide property tax help more targeted to those in need is to offer a property tax circuit-breaker credit. See the box, “Types of Property Tax Credits and Exemptions.”

How Much Do These Preferences Cost the States?

Individual states have collected some information on these preferences’ costs in their tax expenditure reports but many states do not have information on the full cost. A recent study estimated the cost of these breaks in each state and found that on average, preferential tax breaks for seniors reduced state income tax collections by 7 percent in 2013.[28] Based on growth in population and personal income, the current price of these tax breaks is approximately $27 billion a year and will more than double by 2030. The cost varies significantly by state. (See Table 2.)

For example, in Georgia, which fully exempts Social Security income from taxation and offers retirement account income exemptions as well as a higher standard deduction based on age, the preferences cost approximately 12.2 percent of the state’s income tax collections ($1.6 billion).

In contrast, the cost is relatively small in states that offer few preferences or target them by income, such as Connecticut, where the breaks equaled 3.5 percent of income tax collections ($310 million). But Connecticut’s cost will grow as the state recently expanded its senior tax preferences.

In Maryland, which has a moderate level of preferences, the cost is approximately 6.5 percent of income tax collections ($670 million).

| TABLE 2 | ||

|---|---|---|

| Estimated Income Tax Revenue Loss From Elderly Tax Breaks in 2017 | ||

| State | Percent loss | Dollar loss (millions) |

| Alabama | 8.7% | 350 |

| Alaska | N/A | N/A |

| Arizona | 8.9% | 440 |

| Arkansas | 9.2% | 280 |

| California | 3.9% | 3,740 |

| Colorado | 6.8% | 560 |

| Connecticut | 3.5% | 310 |

| District of Columbia | 2.3% | 50 |

| Delaware | 11.5% | 160 |

| Florida | N/A | N/A |

| Georgia | 12.2% | 1,580 |

| Hawaii | 6.7% | 160 |

| Idaho | 8.9% | 180 |

| Illinois | 9.5% | 1,390 |

| Indiana | 8.3% | 510 |

| Iowa | 9.0% | 360 |

| Kansas | 5.0% | 130 |

| Kentucky | 11.1% | 550 |

| Louisiana | 7.2% | 240 |

| Maine | 7.8% | 140 |

| Maryland | 6.5% | 670 |

| Massachusetts | 4.8% | 790 |

| Michigan | 14.0% | 1,490 |

| Minnesota | 3.1% | 390 |

| Mississippi | 12.6% | 250 |

| Missouri | 6.8% | 460 |

| Montana | 4.9% | 70 |

| Nebraska | 3.0% | 70 |

| Nevada | N/A | N/A |

| New Hampshire* | 2.7% | 0 |

| New Jersey | 5.1% | 780 |

| New Mexico | 3.2% | 50 |

| New York | 6.8% | 3,380 |

| North Carolina | 7.7% | 1,080 |

| North Dakota | 2.4% | 10 |

| Ohio | 7.5% | 690 |

| Oklahoma | 9.0% | 310 |

| Oregon | 8.4% | 820 |

| Pennsylvania | 11.7% | 1,540 |

| Rhode Island | 2.3% | 30 |

| South Carolina | 14.6% | 720 |

| South Dakota | N/A | N/A |

| Tennessee* | 0.1% | 0 |

| Texas | N/A | N/A |

| Utah | 3.5% | 150 |

| Vermont | 3.5% | 30 |

| Virginia | 7.3% | 1,100 |

| Washington | N/A | N/A |

| West Virginia | 10.2% | 200 |

| Wisconsin | 7.1% | 620 |

| Wyoming | N/A | N/A |

| United States | 7.0% | 26,830 |

Note: States with N/A do not have income tax. New Hampshire’s and Tennessee’s dollar losses are minimal and round down to zero.

Source: Percent Loss: Ben Brewer, Karen Smith Conway, and Jonathan C. Rork, “Protecting the Vulnerable or Ripe for Reform, State Income Tax Breaks for the Elderly: Then and Now,” Public Finance Review, Vol. 45, No. 4, 2017, pp. 564-594. The percent equals the sum of the differences between income tax paid by senior-headed households in the state and the income tax these households would owe if headed by a taxpayer under 65 years old as a percent of total income tax collections in the state. See box, “Methodology: Estimating Size and Cost of Senior Tax Breaks,“ for more detail. Dollar loss: CBPP calculations of Brewer, Conway, Rork data and Census Bureau state tax collections, 2017

Are Existing Senior Preferences Reaching Their Intended Targets?

One justification for these tax preferences is that seniors live on low, sometimes fixed incomes while their costs, especially for health care and housing, continue to grow. But states enacted many of the breaks decades ago when the senior poverty rate was much higher. And even as poverty has declined among seniors, income and wealth inequality has grown. A study of Medicare recipients found that half of all recipients had incomes below $26,200, while 5 percent had incomes above $100,000 and 1 percent had incomes over $182,900. [29]

The divide between the amount of savings that Medicare recipients have accumulated is even more stark. One quarter of recipients had savings of less than $14,550, while the top 5 percent had savings of more than $1.4 million and the top 1 percent over $4 million.[30] Because many senior tax breaks are not means-tested, a significant share of what states spend on them is directed to high-income taxpayers with the means to pay taxes.

Added exemptions for seniors benefit taxpayers regardless of their income, but in most states they benefit high-income seniors more than low-income ones, unless they also include specific income limits. There are several reasons for that:

- In states with graduated rate structures — ones where the tax rate increases with income — the exemptions’ value depends on the tax rate that the taxpayer pays on each additional dollar of income. Added exemptions provide a greater benefit to higher-income taxpayers because their marginal tax rates are higher, reducing taxes the most for high-income taxpayers who have the means to pay them.

- Exempting retirement account income disproportionately benefits higher-income households. Families with higher incomes, through wages and salaries or returns on stocks and the like, tend to receive more retirement income. Higher salaries translate into higher Social Security and pension payments. Higher incomes also make it possible to accumulate savings in 401(k) and other retirement accounts. So the dollar value of a full exemption for income from these sources is much greater for higher-income families, which are also more likely to be able to take advantage of partial exemptions.

-

Income tax exemptions for seniors don’t benefit taxpayers with income too low to owe state income tax, unlike, say, refundable tax credits, which give taxpayers a partial or full cash refund when the credit amount exceeds their tax liability. It used to be much more common for taxpayers with below-poverty incomes at any age to be subject to state income tax, but now most states exempt low-income taxpayers from it, so only seniors who would otherwise owe tax benefit from the retirement income exemptions. For example, Colorado exempts married couples with no children from its income tax if their income is below 146 percent of the poverty line; as a result, the state’s generous exemption for retirement account income goes only to seniors above this threshold.

Retirement accounts and Social Security make up only about 38 percent of income for the highest-income fifth of elderly (those with incomes of about $72,000 and above), compared to 84 percent of income for the lowest fifth (those with incomes below $13,500), according to the 2014 Consumer Expenditure Survey. (See Figure 7.) Even though low-income seniors depend the most on Social Security, they benefit the least from state exemptions on this income. The federal government already exempts Social Security income from taxation for low- and moderate-income taxpayers. All states at least follow this federal treatment. The states that go further and fully exempt Social Security income are only benefitting taxpayers who are subject to the federal tax — often people of substantial means who have built up assets over time.

Types of Property Tax Credits and Exemptions

The two most common types of property tax reduction programs often targeted to senior taxpayers are homestead exemptions or credits and circuit-breaker-type credits. To understand these property tax reduction methods, it is useful to review the property tax calculation. For the purposes of this example, we will assume the taxpayer owns a home with an assessed value of $250,000 and faces a property tax rate of 2% (that is, 20 mills or $20.00 per $1,000 of value.) The amount of tax owed equals the property tax rate times the assessed value.

With no exemptions or credits the property tax owed on this property would equal $5,000:

.02 (rate) X $250,000 (value) = $5,000 (tax)

Homestead exemptions or credits: Homestead exemptions reduce property taxes by exempting a specific amount of a house’s value from the property tax calculation. The amount can either be a flat dollar amount or a percentage of the assessed value of the home. Using the example above, a flat homestead exemption of $20,000 would reduce taxes owed by $400, to $4,600.

.02 (rate) X [$250,000 (value) - $20,000 (exemption)] =

.02 (rate) X [$230,000 (value after exemption)] = $4,600

A percentage-based homestead exemption would operate similarly except that the amount of the exemption would vary depending on the value of the home. For example, a 10 percent homestead exemption would equal $25,000 in value in the example above. This would reduce the taxable value of the house to $225,000 ($250,000 minus $25,000). Taxes would thus be reduced by $500, to $4,500.

Some states offer homestead credits rather than exemptions, which are reductions in taxes owed as opposed to a reduction in the taxable value. A $400 homestead credit would reduce the taxes owed on the house in the example to $4,600 ($5,000 minus the $400 credit).

Property tax circuit-breaker credit: Property tax circuit breakers are designed to prevent low-income and elderly taxpayers from being “overloaded” by their property tax bill. Most state circuit breaker programs are available only to taxpayers with income below a specified level and include a maximum allowable credit amount. Typically, the state establishes a maximum percentage of income that a qualifying family can be expected to pay in property taxes; if this limit is exceeded, the state provides a credit against taxes owed or a rebate to the taxpayer.

For example, a circuit breaker may limit property taxes owed to no more than 3.5 percent of income. If the owner of the home in the example above had an income of $60,000, the $5,000 in property taxes owed would equal 8.3 percent of income. The taxpayer would receive a credit or rebate equal to the amount needed to bring this percentage down to 3.5 percent, in this example $2,900.

$5,000 (tax owed) – [$60,000 (income) X .035 (maximum share of income allowed)]

$5,000 – $2,100 = $2,900

Source: CBPP calculations

Reducing Senior Tax Breaks Will Not Harm a State’s Economy

Another often-used argument for retaining or creating tax breaks for seniors is that they improve a state’s economy by causing retirees and elderly people to stay in the state or by encouraging them to move there. But there’s no credible evidence to support this claim. State taxes have only a small effect, if any, on the residence decisions of the elderly, recent studies have found. [31] On the whole, after their working years, residents move from a state to retire in warmer areas or in locales with lower housing costs.

Other, earlier research has similarly concluded that the correlation between state taxation and seniors’ decisions on where to live is small, at most. Economist Karen Smith Conway, the leading academic expert on this issue,[32] has with different colleagues found that elderly people who choose to move exhibit only a slight preference for states without income or estate taxes, and that the presence of these taxes does not drive elderly people out of the states levying them. Even these relationships, however, are often not statistically significant or uniform across various measures of tax levels. In summarizing her findings, Conway said, “Put simply, state tax policies toward the elderly have changed substantially while elderly migration patterns have not. . . . Our results, as well as the consistently low rate of elderly interstate migration, should give pause to those who justify offering state tax breaks to the elderly as an effective way to attract and retain the elderly.”[33] She concluded, “Our results are overwhelming in their failure to reveal any consistent effect of state tax policies on elderly migration across state lines.”[34]

A 2004 study of the wealthiest elderly — those who file federal estate tax returns — reached similar conclusions. While the researchers found that high personal income taxes reduced the number of federal estate tax returns filed in the state, the effect was not consistent for different models and was relatively small.[35]

Rather, state reductions in income tax revenue can result in cuts to state services such as education and transportation which boost a state’s economy.[36] That would likely do more harm to a state’s future economic growth than any small benefit that might come from a tax break for seniors.

Ways to Better Target Tax Breaks to Seniors Who Need Them

States can address these large and growing revenue losses while still providing assistance to seniors in need, for instance by including income limits or tests as part of existing tax reduction programs, or making sure that these limits or tests are part of any new senior tax preferences. Or, states could replace these exemptions and credits with ones much more targeted by income.

For example:

- More states could tax a portion of Social Security benefits when the recipient’s total income exceeds a specified amount — as the federal government does — rather than completely exempting such income from taxation. Six states use the same income limits as the federal government for determining whether to tax Social Security benefits, and another seven states partially tax such income using different income limits. Other states should follow suit.

- States that offer exemptions for income from retirement accounts from private- or public-sector jobs could phase them out at a specific income level or only offer them to taxpayers with incomes below a certain level. For example, the District of Columbia eliminated its retirement account income exemption in 2014, and in 2003 Virginia scaled its exemption back by phasing it out for taxpayers at higher income levels. Both changes were parts of larger tax packages.

- States could convert their age-based additional personal exemptions to a higher standard deduction — comparable to the one the federal government offers, and which some states already use. This would target these preferences more to lower- and middle-income taxpayers.

- States could replace these tax exemptions for seniors with an expanded state Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) for seniors. State EITCs offer additional credits on top of the federal EITC, which helps people working in low-wage jobs meet basic needs. Currently workers aged 65 and older are not eligible. Eliminating this age limit would benefit low- and moderate-income seniors who must work after age 65. States could also develop a similar means-tested credit targeted specifically to low-income seniors. Making a state’s tax system less upside-down would also benefit low-income seniors.

- Additional states could rely more on means-tested property tax credits rather than homestead exemptions or credits. For example, circuit breakers provide taxpayers a credit if their income is below a defined level and their property taxes exceed a specified percentage of their income. Currently, 29 states plus the District of Columbia offer property tax circuit-breaker programs, but many of these programs are very limited, and some of the same states also offer homestead exemptions or credits that are not means-tested.[37]

- States could raise the eligibility age for their age-based credits and exemptions to target them to seniors who are less able to pay. While senior poverty rates generally are lower than they were in the past, the rate among those 75 and older is higher than for those between 65 and 75. By better targeting income and property tax reductions on seniors who are more likely to have low incomes, states can free resources to pay for the growing needs of all seniors while still assisting poor elderly residents.

| APPENDIX TABLE 1 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Percent of Population 65 and Older in 2000, 2010, 2017, 2020, and 2030 | |||||

| State | 2000 | 2010 | 2017 | 2020 | 2030 |

| Alabama | 13% | 14% | 16% | 17% | 20% |

| Alaska | 6% | 8% | 11% | 13% | 16% |

| Arizona | 13% | 14% | 17% | 19% | 23% |

| Arkansas | 14% | 14% | 17% | 18% | 20% |

| California | 11% | 11% | 14% | 14% | 17% |

| Colorado | 10% | 11% | 14% | 15% | 17% |

| Connecticut | 14% | 14% | 17% | 17% | 21% |

| Delaware | 13% | 14% | 18% | 18% | 22% |

| District of Columbia | 12% | 11% | 12% | 11% | 10% |

| Florida | 18% | 17% | 20% | 20% | 24% |

| Georgia | 10% | 11% | 13% | 14% | 17% |

| Hawaii | 13% | 14% | 18% | 19% | 22% |

| Idaho | 11% | 12% | 15% | 17% | 19% |

| Illinois | 12% | 13% | 15% | 16% | 18% |

| Indiana | 12% | 13% | 15% | 16% | 19% |

| Iowa | 15% | 15% | 17% | 18% | 20% |

| Kansas | 13% | 13% | 15% | 16% | 19% |

| Kentucky | 12% | 13% | 16% | 17% | 20% |

| Louisiana | 12% | 12% | 15% | 15% | 18% |

| Maine | 14% | 16% | 20% | 21% | 26% |

| Maryland | 11% | 12% | 15% | 15% | 18% |

| Massachusetts | 14% | 14% | 16% | 16% | 19% |

| Michigan | 12% | 14% | 17% | 17% | 21% |

| Minnesota | 12% | 13% | 15% | 16% | 20% |

| Mississippi | 12% | 13% | 15% | 16% | 20% |

| Missouri | 14% | 14% | 16% | 17% | 20% |

| Montana | 13% | 15% | 18% | 20% | 23% |

| Nebraska | 14% | 14% | 15% | 16% | 19% |

| Nevada | 11% | 12% | 15% | 18% | 21% |

| New Hampshire | 12% | 14% | 18% | 19% | 24% |

| New Jersey | 13% | 13% | 16% | 16% | 19% |

| New Mexico | 12% | 13% | 17% | 19% | 23% |

| New York | 13% | 14% | 16% | 16% | 18% |

| North Carolina | 12% | 13% | 16% | 16% | 19% |

| North Dakota | 15% | 14% | 15% | 16% | 18% |

| Ohio | 13% | 14% | 17% | 17% | 20% |

| Oklahoma | 13% | 14% | 15% | 16% | 18% |

| Oregon | 13% | 14% | 17% | 18% | 20% |

| Pennsylvania | 16% | 15% | 18% | 18% | 22% |

| Rhode Island | 15% | 14% | 17% | 17% | 21% |

| South Carolina | 12% | 14% | 17% | 17% | 20% |

| South Dakota | 14% | 14% | 16% | 17% | 20% |

| Tennessee | 12% | 13% | 16% | 17% | 19% |

| Texas | 10% | 10% | 12% | 13% | 15% |

| Utah | 9% | 9% | 11% | 12% | 13% |

| Vermont | 13% | 15% | 19% | 21% | 26% |

| Virginia | 11% | 12% | 15% | 16% | 18% |

| Washington | 11% | 12% | 15% | 16% | 18% |

| West Virginia | 15% | 16% | 19% | 21% | 24% |

| Wisconsin | 13% | 14% | 16% | 18% | 21% |

| Wyoming | 12% | 12% | 16% | 18% | 21% |

| United States | 12% | 13% | 16% | 16% | 19% |

Source: US Census Bureau (2000, 2010, 2017); University of Virginia, Demographics Research Group (2020, 2030)

| APPENDIX TABLE 2 | |

|---|---|

| Treatment of Social Security Income | |

| State | Exemption |

| Alabama | Full |

| Alaska | N/A |

| Arizona | Full |

| Arkansas | Full |

| California | Full |

| Colorado | Partial (see note) |

| Connecticut | Full if income <$50,000/$60,000 |

| Delaware | Full |

| District of Columbia | Full |

| Florida | NA |

| Georgia | Full |

| Hawaii | Full |

| Idaho | Full |

| Illinois | Full |

| Indiana | Full |

| Iowa | Full |

| Kansas | Full if income <$75,000 |

| Kentucky | Full |

| Louisiana | Full |

| Maine | Full |

| Maryland | Full |

| Massachusetts | Full |

| Michigan | Full, if born before or in 1952 (age 67+) Partial, if born after 1952 (age 67+) (see note) |

| Minnesota | Partial (Same as federal) $2,250/ $4,500 subtraction from amount taxed by federal |

| Mississippi | Full |

| Missouri | Full if income <$85,000/$100,000 |

| Montana | Partial: Complies with federal (see note) |

| Nebraska | Full if income <$43,000/$58,000 |

| Nevada | N/A |

| New Hampshire | N/A |

| New Jersey | Full |

| New Mexico | Partial (Same as federal) |

| New York | Full |

| North Carolina | Full |

| North Dakota | Partial (Same as federal) |

| Ohio | Full |

| Oklahoma | Full |

| Oregon | Full |

| Pennsylvania | Full |

| Rhode Island | Partial: Full if income <$81,575/ $101,950 otherwise same as federal |

| South Carolina | Full |

| South Dakota | N/A |

| Tennessee | N/A |

| Texas | N/A |

| Utah | Partial (Same as federal) |

| Vermont | Partial (Same as federal) |

| Virginia | Full |

| Washington | N/A |

| West Virginia* | Partial (Same as federal) |

| Wisconsin | Full |

| Wyoming | N/A |

Note: N/A = no income tax. When two dollar amounts are listed, the first is for single filers and the second for those filing jointly. Colorado: Retirement account income exemption shown in Appendix Table 3 applies to all retirement account income and Social Security combined, up to $24,000/$28,000 (65+) or $20,000/$40,000 (55-64). Michigan: Taxpayers born in 1952 and after must choose either Social Security exemption or all income exemption. See Appendix Table 4. Montana: Complies with federal but uses Montana AGI instead of federal AGI for calculation.

Federal provision: Only taxpayers whose provisional income is $25,000 or higher (single) or $32,000 or higher (married filing jointly) are subject to taxation of their Social Security benefits. Provisional income consists of federal adjusted gross income, tax-exempt interest, certain foreign-source income, and one-half of the taxpayer's Social Security or Railroad Retirement Tier 1 benefit.

West Virginia: Full exemption if income < $50,000/$100,000 being phased in over 3 years starting in 2020.

Source: David Baer, “State Handbook of Economic, Demographic & Fiscal Indicators,” AARP Public Policy Institute, 2003. Updated 2019 by CBPP.

| APPENDIX TABLE 3 | ||

|---|---|---|

| Income Tax Treatment of Retirement Account Income | ||

| State | Private Retirement Account Income Exemption | Public Retirement Account Income Exemption |

| Alabama | Full (defined benefit only) | Full |

| Alaska | N/A | N/A |

| Arizona | $2,500/$5,000 | |

| Arkansas | $6,000/$12,000 | $6,000/$12,000 |

| California | ||

| Colorado* | $20,000/$40,000 (55+) $24,000/$48,000 (65+) |

$20,000/$40,000 (55+) $24,000/$48,000 (65+) |

| Connecticut* | Full (military retirement pay) 25% (teacher retirement pay) |

|

| Delaware | $2,000/$4,000 (under 60) $12,500/$25,000 (60+) |

$2,000/$4,000 (under 60) $12,500/$25,000 (60+) |

| District of Columbia | ||

| Florida | N/A | N/A |

| Georgia | $35,000/$70,000 (62+ or permanently disabled) $65,000/$130,000 (65+) |

$35,000/$70,000 (62+ or permanently disabled) $65,000/$130,000 (65+) |

| Hawaii | Full (if employer funded) | Full |

| Idaho | $33,456/$50,184 less Social Security (65+ or 62+ and disabled) | |

| Illinois | Full | Full |

| Indiana | $6,250 (military retirement pay) $16,000 less Social Security (62+, federal civil service annuity only) |

|

| Iowa | $6,000/$12,000 (55+ or disabled) | $6,000/$12,000 (55+ or disabled) Full (military retirement pay) |

| Kansas | Full | |

| Kentucky | $31,110/$62,220 | Partially exempt if retired after 12/31/1997 Fully exempt if retired before 1/1/1998 |

| Louisiana | $6,000/$12,000 (65+) | Full |

| Maine | $10,000/$20,000 less Social Security | $10,000/$20,000 less Social Security All military retirement pay |

| Maryland | $30,600/$61,200 less Social Security (65+ or disabled) | $30,600/$61,200 less Social Security (65+ or disabled) $15,000 for military and some law enforcement and emergency personnel (55+) |

| Massachusetts | Full | |

| Michigan* | See Appendix Table 4 and note | See Appendix Table 4 and note. |

| Minnesota | Full (military retirement pay) | |

| Mississippi | Full | Full |

| Missouri | $6,000/$12,000 if income <$25,000/$32,000 | $37,720/$75,440 if income <$85,000/$100,000 Full (military retirement pay) |

| Montana | Up to $4,180/$8,360 (phase-out begins when AGI >$34,820) | Up to $4,180/$8,360 (phase-out begins when AGI >$34,820) |

| Nebraska | Partial (military retirement pay) | |

| Nevada | N/A | N/A |

| New Hampshire | N/A | N/A |

| New Jersey | $45,000/$60,000 if income <$100,000 (62+ or blind/disabled) | $45,000/$60,000 if income <$100,000 (62+ or blind/disabled) Full (military retirement income) |

| New Mexico | ||

| New York | $20,000/$40,000 (59.5+) | Full |

| North Carolina | Full exemption applies only to certain retirement plans — per Supreme Court Case Bailey v. State of North Carolina | |

| North Dakota | ||

| Ohio | Credit of up to $200 depending on age if income <$100,000 | Credit of up to $200 depending on age if income <$100,000 |

| Oklahoma | $10,000/$20,000 | $10,000/$20,000 75% or $10,000 — whichever is more (military retirement pay) |

| Oregon | Tax credit up to 9% (62+) if income <$22,500/$45,000 and Social Security <$7,500/$15,000 | Tax credit up to 9% (62+) if income <$22,500/$45,000 and Social Security <$7,500/$15,000 Full exemption of federal pension income if all federal service occurred before 10/1/1991 Partial exemption of federal pension income if federal service occurred before and after 10/1/1991 |

| Pennsylvania | Full | Full |

| Rhode Island | $15,000/$30,000 if born before 1/1/1953 and income <$81,900/$102,400 | $15,000/$30,000 if born before 1/1/1953 and income <$81,900/$102,400 |

| South Carolina | $3,000/$6,000 (age <65) $10,000/$20,000 (65+) |

$3,000/$6,000 (age <65) $10,000/$20,000 (65+) |

| South Dakota | N/A | N/A |

| Tennessee | N/A | N/A |

| Texas | N/A | N/A |

| Utah | Credit of up to $450/$900 depending on income if born on or before 12/31/1952 | Credit of up to $450/$900 depending on income if born on or before 12/31/1952 |

| Vermont | ||

| Virginia | ||

| Washington | N/A | N/A |

| West Virginia | Full (state/local police, sheriffs, firefighters, military) $2,000 (other state/local/federal public employees) |

|

| Wisconsin | $5,000/$10,000 if income <$15,000/$30,000 (65+) | $5,000/$10,000 in income <$15,000/$30,000 (65+) Full if military or depending on start date of retirement plan |

| Wyoming | N/A | N/A |

Note: When two dollar amounts are listed, the first is for single filers and the second for those filing jointly.

Colorado: Retirement account income exemption applies to all retirement account income and Social Security combined, up to $24,000/$28,000 (65+) or $20,000/$40,000 (55-64). Connecticut is phasing in a full exemption for retirement account income that will be effective starting in 2019.

Michigan provides different exemptions based on year born. Taxpayers born before 1952 receive more generous exemptions than the ones shown in Appendix Table 4. In addition, those receiving public pensions as of 2013 from agencies not covered by Social Security can exempt $35,000 (single)/$55,000 (joint)/$75,000 (if both worked for “uncovered” agency.

Source: CBPP analysis of 2018 state income tax forms

| APPENDIX TABLE 4 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Other Income Tax Preferences | |||

| State | Added Exemption (65+) | Higher Standard Deduction (65+) | Other |

| Alabama | |||

| Alaska | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Arizona | $2,100/$4,200 | ||

| Arkansas | $26/$52 credit | Additional $26/$52 if not receiving retirement income (65+) | |

| California | $118/$236 credit | Special credit up to $1,434 (0.02*taxable income) for senior head of household (65+) with AGI <$76,082 | |

| Colorado | $1,600/$2,600 | ||

| Connecticut | |||

| Delaware | $110/$220 credit (60+) | $2,500/$5,000 | |

| District of Columbia | $1,300/$2,600 | ||

| Florida | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Georgia | $1,300/$2,600 | ||

| Hawaii | $1,144/$2,288 | ||

| Idaho | $1,600/$2,600 | Additional $1.67 per month for grocery credit (65+) — up to $20 additional credit for full year | |

| Illinois | $1,000/$2,000 | ||

| Indiana | $1,000/$2,000 if AGI >=$40,000 $1,500/$3,000 if AGI <$40,000 |

Credit of up to $100/$140 (65+ with AGI <$10,000) | |

| Iowa | $20/$40 credit | ||

| Kansas | $850/$1,400 | ||

| Kentucky | $40/$80 credit | ||

| Louisiana | $1,000/$2,000 | ||

| Maine | $1,600/$2,600 | ||

| Maryland | $1,000/$2,000 | ||

| Massachusetts | $700/$1,400 | ||

| Michigan* | $20,000/$40,000 exemption against all income with no personal exemptions or exemption of Social Security, military compensation and pension, and railroad/Michigan National Guard pension with personal exemptions (67+)* | ||

| Minnesota | $1,600/$2,600 | Exemption of $9,600/$12,000 on any income minus Social Security (phases out between $14,500/$18,000 and $33,700/$42,000) | |

| Mississippi | $1,500/$3,000 | ||

| Missouri | $1,600/$2,600 | ||

| Montana | $2,440/$4,880 | Exemption up to $800/$1,600 of interest income in MT AGI (65+) | |

| Nebraska | $1,600/$2,600 | ||

| Nevada | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| New Hampshire | $1,200/$2,400 | ||

| New Jersey | $1,000/$2,000 | ||

| New Mexico | $1,600/$2,600 | Exemption up to $8,000 if AGI <=$28,500/$51,000 (65+) | |

| New York | |||

| North Carolina | |||

| North Dakota | $1,600/$2,600 | ||

| Ohio | Credit of $50 per return if income < $100,000 (65+) | ||

| Oklahoma | $1,000 single with AGI <=$15,000 $2,000 joint if AGI <=$25,000 |

||

| Oregon | $1,200/$2,000 | ||

| Pennsylvania | |||

| Rhode Island | |||

| South Carolina | $1,600/$2,600 | Deduction of $15,000/$30,000 less retirement/military retirement deductions | |

| South Dakota | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Tennessee | Complete exemption if total income <$37,000/$68,000 | ||

| Texas | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Utah | $1,600/$2,600 | ||

| Vermont | $1,000/$2,000 | ||

| Virginia | $800/$1,600 | Deduction of $12,000/$24,000 (80+) Maximum deduction of $12,000/$24,000 for incomes less than $50,000/$75,000 (65+) — deduction decreases as income increases |

|

| Washington | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| West Virginia | Deduction of up to $8,000/$16,000 depending on income source (65+) | ||

| Wisconsin | $250/$500 | ||

| Wyoming | N/A | N/A | N/A |

*This applies to Michigan taxpayers age 67 or older born after 1952. Taxpayers born before 1952 receive more generous exemptions. Details are available here: https://www.michigan.gov/documents/taxes/2018RetirementPensionBenefitsChart_644900_7.pdf.

When two dollar amounts are listed, the first is for single filers and the second for those filing jointly.

Source: CBPP analysis of 2018 state income tax forms

| APPENDIX TABLE 5 | ||

|---|---|---|

| State Homestead Exemption and Credit Programs | ||

| State | General | Seniors |

| Alabama | Yes | Yes |

| Alaska | Local option | Yes |

| Arizona | Yes | |

| Arkansas | Yes | |

| California | Yes | |

| Colorado | Yes | |

| Connecticut | ||

| Delaware | Yes | |

| District of Columbia | Yes | Yes |

| Florida | Yes | Local option |

| Georgia | Yes | Yes |

| Hawaii | Local option | Local option |

| Idaho | Yes | |

| Illinois | Yes | Yes |

| Indiana | Yes | Yes |

| Iowa | Yes | |

| Kansas | Yes | Yes |

| Kentucky | ||

| Louisiana | Yes | |

| Maine | Yes | Yes |

| Maryland | Yes | Local option |

| Massachusetts | Local option | Yes |

| Michigan | Yes | |

| Minnesota | Yes | |

| Mississippi | Yes | Yes |

| Missouri | ||

| Montana | ||

| Nebraska | ||

| Nevada | ||

| New Hampshire | Local option | |

| New Jersey | Yes | |

| New Mexico | ||

| New York | Yes | Yes |

| North Carolina | Yes | |

| North Dakota | ||

| Ohio | Yes | Yes |

| Oklahoma | Yes | |

| Oregon | ||

| Pennsylvania | Yes | |

| Rhode Island | ||

| South Carolina | Yes | Yes |

| South Dakota | ||

| Tennessee | Yes | |

| Texas | Yes | Yes |

| Utah | Yes | Yes |

| Vermont | ||

| Virginia | Local option | |

| Washington | ||

| West Virginia | Yes | |

| Wisconsin | Yes | |

| Wyoming | ||

Source: Lincoln Institute of Land Policy, “Estimating Tax Savings from Homestead Exemptions and Property Tax Credits,” 2015. Updated by CBPP and with Lincoln Institute of Land Policy, “Significant Features of the Property Tax, State-by-State Property Tax in Detail,” 2017.

End Notes

[1] Projected Age Groups and Sex Composition of the Population: Main Projections Series for the United States, 2017-2060, U.S. Census Bureau.

[2] Ben Brewer, Karen Smith Conway, and Jonathan Rork, “Protecting the Vulnerable or Ripe for Reform? State Income Tax Breaks for the Elderly — Then and Now,” Public Finance Review, Vol., No. 4, 2017, pp. 564-594, https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/1091142116665903 (requires subscription).

[3] $27 billion estimated by applying the 7 percent cost to 2017 state personal income tax collections.

[4] Percent below poverty based on the official poverty measure.

[5] Peter Whoriskey, “For many older Americans, the rat race is over. But the inequality isn’t,” Washington Post, October 18, 2017, https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/wonk/wp/2017/10/18/for-many-older-americans-the-rat-race-is-over-but-the-inequality-isnt/?utm_term=.b424d1bdf510; Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, “Preventing Ageing Unequally: How does the United States Compare?” http://www.oecd.org/unitedstates/PAU2017-USA-En.pdf.

[6] “Changes in U.S. Family Finances from 2013 to 2016: Evidence from the Survey of Consumer Finances,” Federal Reserve Bulletin, Vol. 103, No. 3, September 2017, https://www.federalreserve.gov/publications/files/scf17.pdf.

[7] Nari Rhee, “Race and Retirement Insecurity in the United States,” National Institute on Retirement Security, December 2013, https://www.nirsonline.org/reports/race-and-retirement-insecurity-in-the-united-states/.

[8] These figures are based on the official poverty measure. Using the Census Bureau Supplemental Poverty Measure (SPM), 14.1 percent of seniors have below-poverty incomes compared to 13.9 percent of all people, according to the most recent data. The percent of seniors in poverty has also declined since the 1970s using the SPM.

[9] William J. Wiatrowski, “The Last Private Industry Pension Plans: A Visual Essay,” BLS Monthly Labor Review, December 2012, https://www.bls.gov/opub/mlr/2012/12/art1full.pdf

[10] CBPP calculations of IRS data.

[11] Rhee.

[12] Social Security Office of Retirement and Disability Policy, “Income of the Aged Chartbook, 2014,” https://www.ssa.gov/policy/docs/chartbooks/income_aged/2014/iac14.html.

[13] Dedrick Asante-Muhammed et al., “The Ever-Growing Gap: Without Change, African-American and Latino Families Won’t Match White Wealth for Centuries,” Racial Wealth Divide Initiative, Institute for Policy Studies, August 2016.

[14] “Changes in U.S. Family Finances from 2013 to 2016: Evidence from the Survey of Consumer Finances,” Federal Reserve Bulletin, Vol. 103, No. 3, September 2017, https://www.federalreserve.gov/publications/files/scf17.pdf.

[15] Matthew A. Davis et al., “Trends and Disparities in the Number of Self-reported Healthy Older Adults in the United States, 2000 to 2014,” JAMA Internal Medicine, Vol. 117, No. 11, November 2017, https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamainternalmedicine/fullarticle/2653447.

[16] David M. Cutler, Kaushik Ghosh, and Mary Beth Landrum, “Evidence for Significant Compression of Morbidity in the Elderly US Population, National Bureau of Economic Research, June 2014, https://www.nber.org/chapters/c12966.pdf.

[17] Brewer, Conway, and Rork. See box, “Methodology: Estimating Size and Cost of Senior Tax Breaks.”

[18] Excludes New Hampshire and Tennessee.

[19] In these determinations, the federal government uses “provisional” income, which consists of federal adjusted gross income plus one-half of Social Security benefits, tax-exempt interest, and certain foreign-source income.

[20] West Virginia will phase in an exemption of all Social Security income for taxpayers with incomes below $50,000 (for single filers) and $100,000 (for joint filers) starting in 2020.

[21] CBPP calculations of Bureau of Labor Statistics Current Employment Statistics data, https://www.bls.gov/cex/2016/aggregate/age.pdf.

[22] Social Security, Income of the Aged, 2014, https://www.ssa.gov/policy/docs/chartbooks/income_aged/2014/iac14.html#table20.

[23] There also are Roth IRAs and Roth defined contribution plans in which after-tax dollars are deposited. The withdrawals from those accounts, including withdrawals of earnings on those accounts, are not taxed.

[24] The seven states are California, Minnesota, Nevada, New Mexico, North Dakota, Vermont, and Virginia. These counts do not include states that exempt only military pensions.

[25] These are Alabama, Connecticut, New York, North Carolina, Pennsylvania, and Rhode Island.

[26] Some 19 states offer retirement income exemptions of $5,000 or more, while the average added personal exemption is $1,200 and the typical added standard exemption is $1,600. This is reflected in estimates of the cost of these exemptions in state tax expenditure reports. For example, Delaware’s Social Security exemption and pension exemption cost $70 million each while the cost of the added personal exemption is only $18 million. Similarly, Maryland’s Social Security and pension exemptions cost $380 million in total and the added personal exemption costs $31 million.

[27] The federal elderly credit is up to $5,000 for single filers and up to $7,500 for joint filers.

[28] Brewer, Conway, and Rork. See box, “Methodology: Estimating Size and Cost of Senior Tax Breaks.”

[29] Medicare recipients include both aged and disabled persons, but aged individuals make up 85 percent of all recipients.

[30] Gretchen Jacobson et al., “Income and Assets of Medicare Beneficiaries, 2016-2035,” Kaiser Family Foundation, April 2017, http://files.kff.org/attachment/Issue-Brief-Income-and-Assets-of-Medicare-Beneficiaries-2016-2035.

[31] Michael Mazerov, “State Taxes Have a Negligible Impact on Americans’ Interstate Moves,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, revised May 21, 2014, https://www.cbpp.org/research/state-budget-and-tax/state-taxes-have-a-negligible-impact-on-americans-interstate-moves.

[32] Karen Smith Conway and Andrew J. Houtenville, “Do the Elderly ‘Vote with Their Feet?’” Public Choice, Vol. 97, No. 4, 1998; Conway and Houtenville, “Elderly Migration and State Fiscal Policy: Evidence from the 1990 Census Migration Flows,” National Tax Journal, Vol. 54, No. 1, 2001; Conway and Houtenville, “Out with the Old, in with the Old: A Closer Look at Younger Versus Older Elderly Migration,” Social Science Quarterly, Vol. 84, No. 2, February 2003; Conway and Jonathan C. Rork, “State ‘Death’ Taxes and Elderly Migration: The Chicken or the Egg?” National Tax Journal, Vol. 59, No. 1, March 2006; Conway and Rork, “No Country for Old Men (Or Women): Do State Tax Policies Drive Away the Elderly?” National Tax Journal, Vol. 65, No. 2, June 2012.

[33] Conway and Rork, 2012.

[34] Ibid.

[35] Jon Bakija and Joel Slemrod, “Do the Rich Flee from High State Taxes? Evidence from Federal Estate Tax Returns,” National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper 10645, July 2004. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/5185299_Do_the_Rich_Flee_from_High_State_Taxes_Evidence_from_Federal_Estate_Tax_Returns

[36] Erica Williams, “A Four-Point Fiscal Policy Blueprint for Building Thriving State Economies,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, updated October 5, 2017, https://www.cbpp.org/research/state-budget-and-tax/a-fiscal-policy-agenda-for-stronger-state-economies.

[37] Aidan Davis, “Property Tax Circuit Breakers in 2018,” Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, September 2018, https://itep.org/property-tax-circuit-breakers-in-2018/.