- Home

- Social Security

- Social Security Lifts More People Above ...

Social Security Lifts More People Above the Poverty Line Than Any Other Program

Social Security benefits play a vital role in reducing poverty in every state, and they lift more people above the poverty line than any other program in the United States. Without Social Security, 22.7 million more adults and children would be below the poverty line, according to our analysis using the March 2023 Current Population Survey. Although most of those whom Social Security keeps out of poverty are aged 65 or older, 6.2 million are under age 65, including 900,000 children. (See Table 1.) Social Security is particularly important for older women and people of color, who have fewer retirement resources outside of Social Security. Depending on their design, reductions in Social Security benefits could significantly increase poverty, particularly among older adults.

| TABLE 1 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Effect of Social Security on Poverty (Official Poverty Measure), 2022 | |||

| Percent in Poverty | |||

| Age Group | Excluding Social Security | Including Social Security | Number Lifted Above the Poverty Line by Social Security |

| Children Under 18 | 16.2% | 15.0% | 868,000 |

| Adults Aged 18-64 | 13.3% | 10.6% | 5,321,000 |

| Adults Aged 65 and Over | 38.7% | 10.2% | 16,508,000 |

| Total, All Ages | 18.4% | 11.5% | 22,696,000 |

Note: Figures are rounded to the nearest 1,000. Figures may not sum to totals due to rounding.

Source: CBPP analysis of data from the U.S. Census Bureau’s March 2023 Current Population Survey

Social Security Lifts 16.5 Million People Aged 65 or Older Above the Poverty Line

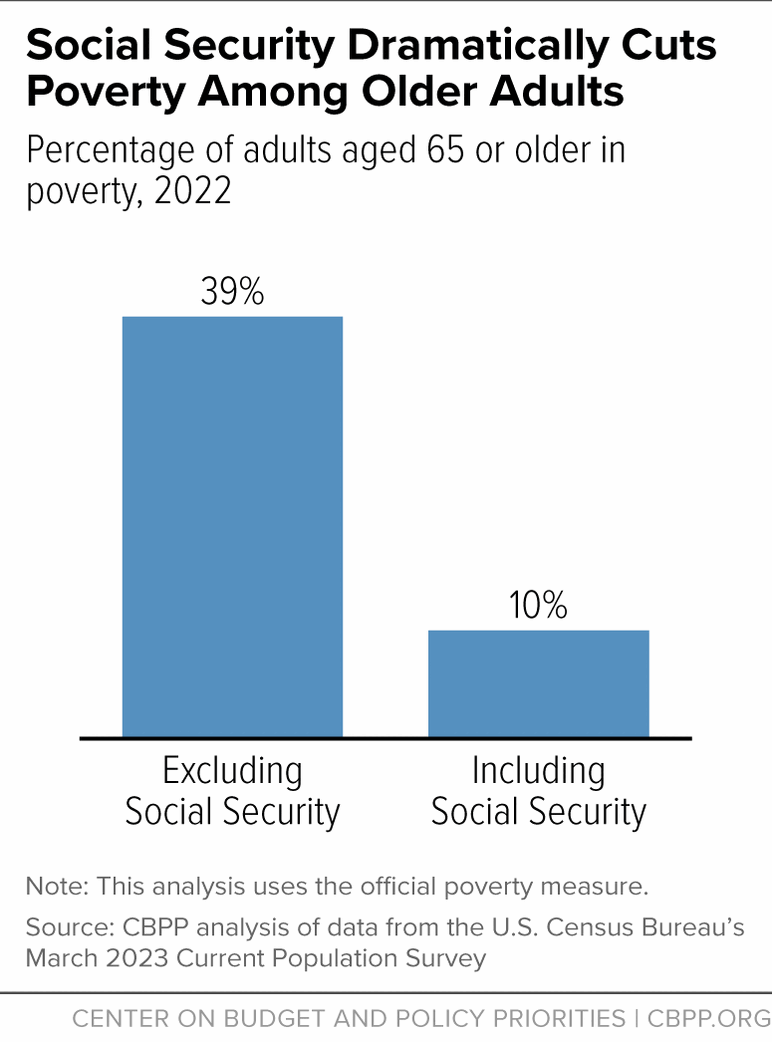

Most people aged 65 and older receive the majority of their income from Social Security.[1] Without Social Security benefits, 38.7 percent of older adults would have incomes below the official poverty line, all else being equal; with Social Security benefits, only 10.2 percent do. (See Figure 1.) The benefits lift 16.5 million older adults above the poverty line, these estimates show.

Comprehensive studies that match Census survey data to administrative records suggest that the official estimates overstate older adults’ reliance on Social Security but confirm that Social Security lifts millions of older adults above the poverty line and dramatically reduces the poverty rate among people aged 65 and older. (See Appendix for more information.)

Social Security Lifts 900,000 Children Above the Poverty Line

Social Security is important for children and their families as well as for older adults. About 5.7 million children under age 18 (9 percent of all children in the U.S.) lived in families that received income from Social Security in 2022, according to Census data. This figure includes children who received their own benefits as dependents of retired, disabled, or deceased workers, as well as those who lived with parents or relatives who received Social Security. In all, Social Security lifts 900,000 children above the poverty line.[2]

Social Security records show that 2.6 million children under age 18 qualified for Social Security payments in December 2022. (See Appendix Table 2.) Of these children, 1.3 million were the survivor of a deceased worker. Another 1.0 million received payments because their parent had a severe disability. And 322,000 children under 18 received payments because their parent was retired.[3]

Social Security Protects Groups That Are Particularly Vulnerable to Poverty

Social Security is especially important for women and people of color. Women tend to earn less than men, take more time out of the paid workforce, live longer, accumulate less savings, and receive smaller pensions. Social Security brings 9.4 million older women above the poverty line, as Table 2 shows.

Black and Latino workers benefit substantially from Social Security because they have higher disability rates and lower lifetime earnings than white workers, on average. In addition, Black workers have higher rates of premature death than white workers, and so their spouses and children are more likely to be eligible for Social Security survivor benefits. Latino workers have longer average life expectancies than white workers, which means they have more years to collect retirement benefits. Without Social Security, the poverty rate among older Latino adults would be 43 percent, and the poverty rate among older Black adults would be 47.4 percent.[4]

| TABLE 2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Effect of Social Security on Age 65+ Poverty by Sex and Race (Official Poverty Measure), 2022 | |||

| Percent in Poverty | |||

| Demographic Group | Excluding Social Security | Including Social Security | Number Lifted Above the Poverty Line by Social Security |

| Sex | |||

| Men | 36.1% | 9.0% | 7,138,000 |

| Women | 40.9% | 11.2% | 9,370,000 |

| Race/Ethnicity | |||

| White | 37.4% | 8.2% | 12,569,000 |

| Black | 47.4% | 17.5% | 1,688,000 |

| Latino | 43.0% | 16.9% | 1,421,000 |

| Asian | 32.7% | 12.7% | 595,000 |

| Other | 39.2% | 12.1% | 235,000 |

| Total, Age 65+ | 38.7% | 10.2% | 16,508,000 |

Note: Figures are rounded to the nearest 1,000. Figures may not sum to totals due to rounding.

Source: CBPP analysis of data from the U.S. Census Bureau’s March 2023 Current Population Survey

Social Security Reduces Poverty in Every State

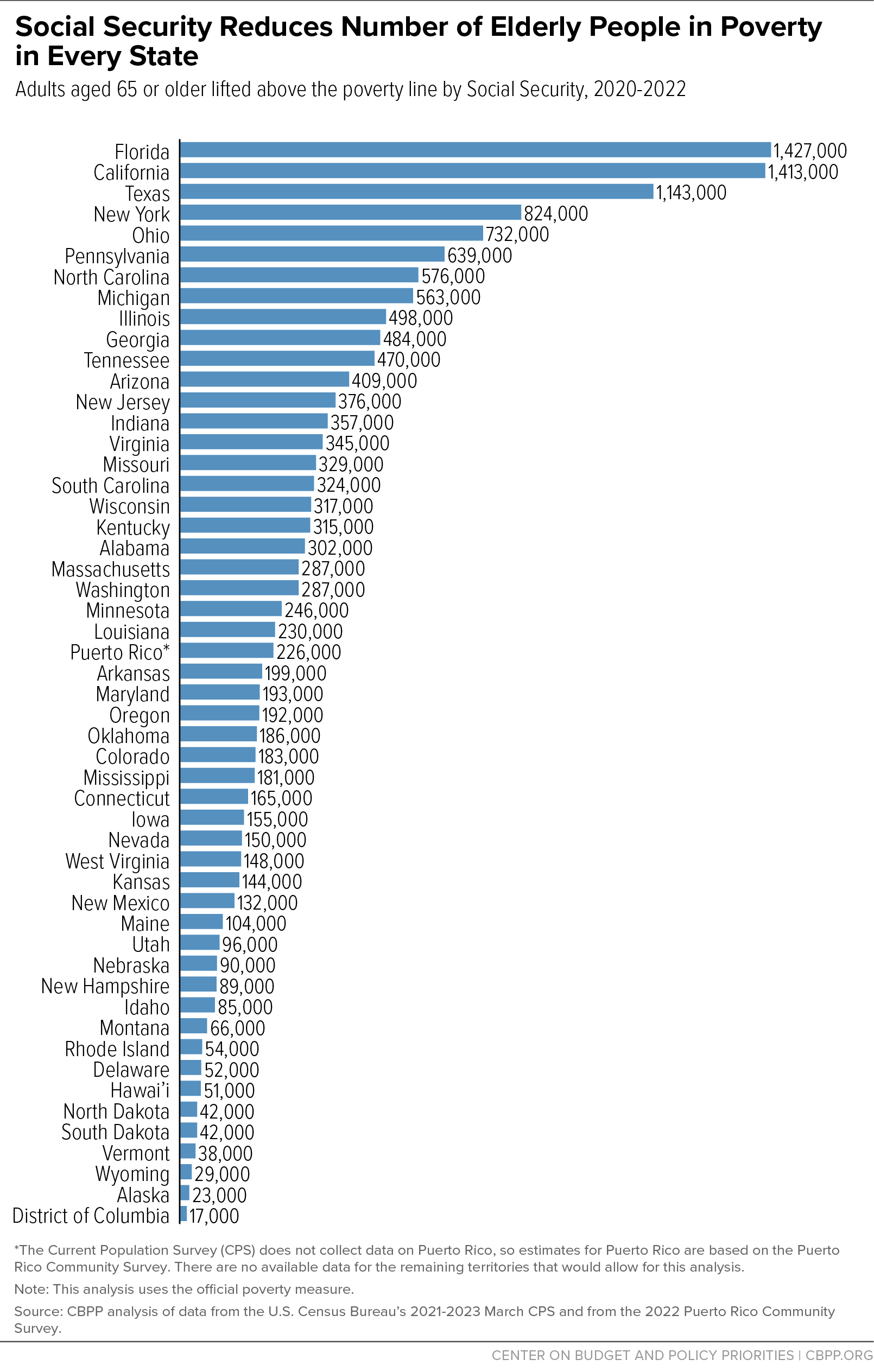

Social Security reduces poverty dramatically among older adults in every state as well as Washington, D.C. and Puerto Rico, as Figure 2 and Appendix Table 1 show. Without Social Security, the poverty rate for those aged 65 and over would meet or exceed 40 percent in over a third of states; with Social Security, it is less than 10 percent in nearly two-thirds of states. Social Security lifts more than 1 million older adults above the poverty line in Florida, California, and Texas, and over half a million in New York, Ohio, Pennsylvania, North Carolina, and Michigan.

Technical Note

This analysis uses the Census Bureau’s official definition of poverty (except for the box, “Social Security’s Effect on Poverty Using the Supplemental Poverty Measure”). In determining poverty status, the Census Bureau compares a family’s cash income before taxes with poverty thresholds that vary by the size and age of the family. The poverty thresholds in 2022 were $14,040 for an elderly individual, $17,710 for an elderly couple, and $29,950 for an average family of four.[5] To calculate the anti-poverty effects of Social Security, we determined each family’s poverty status twice — first excluding and then including the family’s Social Security benefits.

Our analysis considers the non-institutionalized population using data from the Census Bureau’s Current Population Survey (CPS), the survey that is used to produce official poverty estimates.[6] Each March the CPS collects information on personal income, health coverage, and other social and economic characteristics for the previous year. The national estimates reported here are for 2022. The state-by-state estimates are based on a three-year average of CPS data (2020 to 2022) to improve their reliability. The estimate for Puerto Rico is based on a single year of data (2022) using the Puerto Rico Community Survey.

This analysis does not consider other changes that would occur in the absence of Social Security. If Social Security did not exist, many individuals aged 65 or older likely would have saved somewhat more and worked somewhat longer, and many might live with their adult children rather than in their own households. Other studies confirm, however, that Social Security has made a very large contribution to reducing poverty and that cutting Social Security benefits could substantially increase poverty among older adults.[7]

Appendix

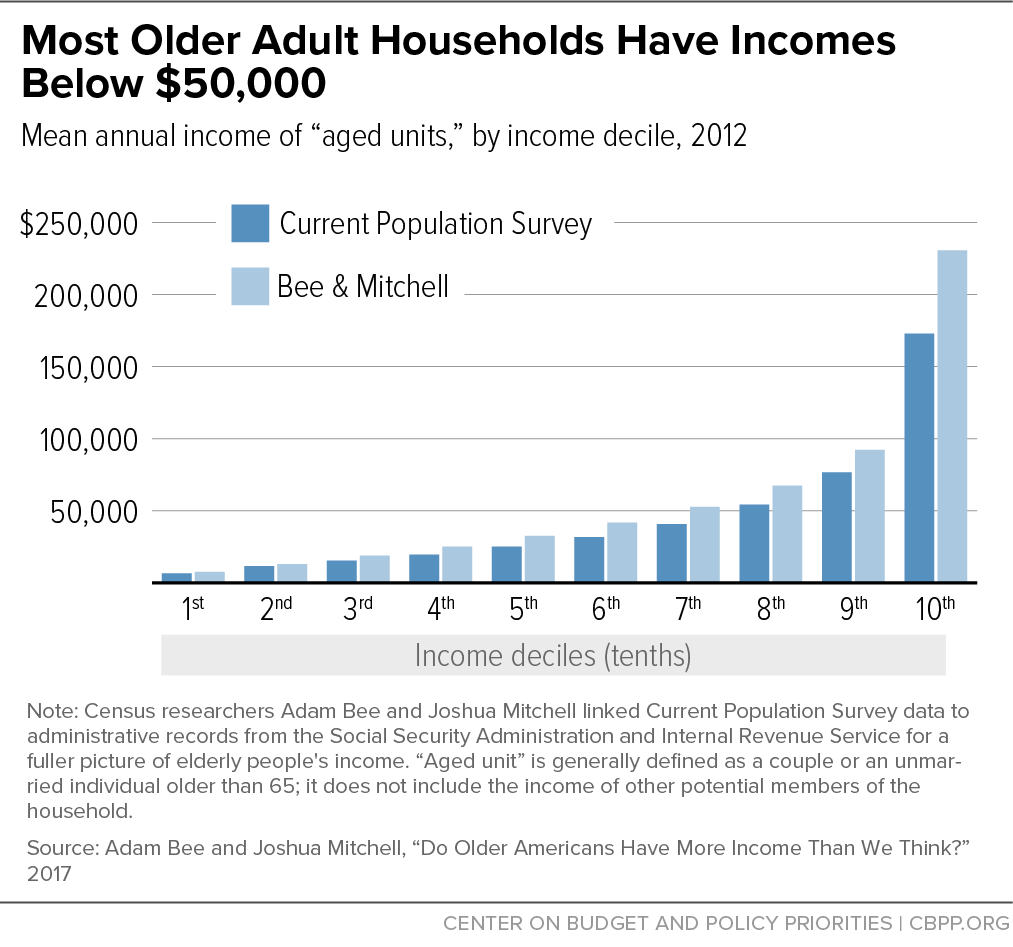

A 2017 study by Adam Bee and Joshua Mitchell of the Census Bureau matched the CPS survey responses used for official poverty statistics to administrative data from the Social Security Administration (SSA), the Internal Revenue Service, and other government sources.[8] They found that official estimates overstate older adults’ reliance on Social Security and poverty rates among older adults, but confirmed that Social Security lifts millions of adults aged 65 and older above the poverty line and dramatically reduces the poverty rate among these adults. They did not find significant underreporting of income among people of working age. Further study has confirmed their findings using more recent data, but Bee and Mitchell’s study remains the most comprehensive analysis.[9]

Bee and Mitchell found that survey respondents generally reported accurately whether they received Social Security or earnings, but not whether they received pension income. Roughly half of older adult respondents who received pension income — either income from traditional defined-benefit pensions or withdrawals from defined-contribution pensions like 401(k)s or individual retirement accounts — failed to report this, particularly respondents whose pension income was small or inconsistent. On the other hand, respondents who reported receiving Social Security, earnings, or pension income generally reported accurately the amount they received from those sources.

Most retirees have modest incomes, save for some at the top of the income spectrum. Bee and Mitchell show that most low-income older adult households have very little pension income, if any; the majority of older adult households in the bottom third of the income distribution receive no pension income at all (compared to more than 80 percent in the top two-thirds). Older adult households had a median income of about $44,000 in 2012 (compared to about $34,000 using the CPS alone, about a 30 percent difference). Further, about 1 in 4 retiree households lived on less than $20,000, and the majority lived on $50,000 or less. (See Appendix Figure 1.) Meanwhile, the wealthiest tenth of older adult households had an average income of $230,000.

Bee and Mitchell’s study confirms Social Security’s large effect on poverty among older adults, but the enhanced data reduce both the poverty rate for these adults and the number of older adults lifted above the poverty line, compared to the official measures. The study estimates an elderly poverty rate in 2012 of nearly 7 percent, rather than the official rate of 9 percent. It also estimates that Social Security lifted about 3 in 10 older people — 10 million — above the poverty line, about one-third lower than official estimates.

The study also confirms that Social Security remains the foundation of retirement income. It is the largest single source of income for older adults, providing the majority of income for half of retirees and at least 90 percent of income for 18 percent of retirees. These rates of reliance are similar to Health and Retirement Survey and Survey of Income and Program Participation estimates.[10] However, they indicate significantly less reliance on Social Security than the CPS alone, which estimated that about 65 percent of older adults received at least half of their income from Social Security and that 36 percent received at least 90 percent. Bee and Mitchell’s study also finds that Supplemental Security Income (SSI) plays a more important role in older adults’ income than official figures suggest, as many older adults with low incomes confuse SSI with Social Security.

Bee and Mitchell’s data extend only through 2012. Their findings were replicated by SSA researchers using 2016 data but cannot easily be extrapolated to future retirees. Trends strongly indicate that the composition and distribution of retirement income will change significantly. Bee and Mitchell found that roughly two-thirds of non-Social Security retirement income for current retirees came from traditional defined-benefit pensions, which have largely been replaced by defined-contribution plans in the private sector for today’s workers. Future retirees will be much less likely to have these pension benefits, and more of their retirement income will come from defined-contribution plans and individual retirement accounts, in which balances are highly unequal.

| APPENDIX TABLE 1 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Effect of Social Security on Poverty Among Adults Aged 65 and Older by State (Official Poverty Measure), 2020-2022 | |||

| Percent in Poverty | |||

| Excluding Social Security | Including Social Security | Number Lifted Above the Poverty Line by Social Security | |

| Alabama | 48.0% | 13.8% | 302,000 |

| Alaska | 30.2% | 7.4% | 23,000 |

| Arizona | 40.3% | 10.2% | 409,000 |

| Arkansas | 48.5% | 11.3% | 199,000 |

| California | 34.2% | 10.8% | 1,413,000 |

| Colorado | 29.3% | 8.1% | 183,000 |

| Connecticut | 31.7% | 7.7% | 165,000 |

| Delaware | 31.4% | 6.3% | 52,000 |

| District of Columbia | 38.9% | 20.2% | 17,000 |

| Florida | 42.6% | 11.3% | 1,427,000 |

| Georgia | 42.1% | 10.9% | 484,000 |

| Hawai’i | 25.6% | 7.9% | 51,000 |

| Idaho | 34.1% | 7.0% | 85,000 |

| Illinois | 33.9% | 9.9% | 498,000 |

| Indiana | 40.5% | 7.8% | 357,000 |

| Iowa | 31.2% | 4.8% | 155,000 |

| Kansas | 34.5% | 5.6% | 144,000 |

| Kentucky | 51.7% | 12.8% | 315,000 |

| Louisiana | 45.6% | 14.3% | 230,000 |

| Maine | 40.6% | 7.5% | 104,000 |

| Maryland | 24.4% | 5.7% | 193,000 |

| Massachusetts | 32.5% | 9.5% | 287,000 |

| Michigan | 39.2% | 9.1% | 563,000 |

| Minnesota | 32.4% | 6.0% | 246,000 |

| Mississippi | 52.3% | 14.9% | 181,000 |

| Missouri | 38.6% | 7.8% | 329,000 |

| Montana | 40.1% | 10.3% | 66,000 |

| Nebraska | 34.2% | 6.7% | 90,000 |

| Nevada | 38.5% | 10.1% | 150,000 |

| New Hampshire | 36.2% | 7.0% | 89,000 |

| New Jersey | 31.1% | 7.3% | 376,000 |

| New Mexico | 45.1% | 13.4% | 132,000 |

| New York | 35.4% | 12.0% | 824,000 |

| North Carolina | 43.8% | 11.7% | 576,000 |

| North Dakota | 41.1% | 6.1% | 42,000 |

| Ohio | 42.2% | 9.3% | 732,000 |

| Oklahoma | 42.5% | 12.5% | 186,000 |

| Oregon | 30.6% | 6.8% | 192,000 |

| Pennsylvania | 35.2% | 8.7% | 639,000 |

| Puerto Rico* | 70.3% | 57.1% | 226,000 |

| Rhode Island | 32.9% | 6.0% | 54,000 |

| South Carolina | 42.3% | 9.3% | 324,000 |

| South Dakota | 35.2% | 8.2% | 42,000 |

| Tennessee | 45.9% | 9.3% | 470,000 |

| Texas | 39.9% | 11.4% | 1,143,000 |

| Utah | 31.4% | 6.7% | 96,000 |

| Vermont | 34.6% | 6.8% | 38,000 |

| Virginia | 36.0% | 8.9% | 345,000 |

| Washington | 33.4% | 8.3% | 287,000 |

| West Virginia | 54.8% | 13.0% | 148,000 |

| Wisconsin | 36.8% | 4.5% | 317,000 |

| Wyoming | 35.8% | 8.0% | 29,000 |

| Total, Persons Aged 65+ | 38.0% | 9.8% | 15,799,000 |

Note: Income is family cash income. The poverty rate “including Social Security” is the official poverty rate. Figures are rounded to the nearest 1,000.

* Totals do not include Social Security beneficiaries who live in Puerto Rico, other U.S. Territories, or abroad because the Current Population Survey (CPS) does not collect data for them. Estimates for Puerto Rico are based on the Puerto Rico Community Survey.

Source: CBPP analysis of data from the U.S. Census Bureau’s 2021-2023 March CPS and 2022 Puerto Rico Community Survey

| APPENDIX TABLE 2 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Social Security Beneficiaries by State or Other Area and Age, 2022 | ||||

| Total | Aged 65 and Older | Aged 18-64 | Children Under 18 | |

| Alabama | 1,168,912 | 834,196 | 271,274 | 63,442 |

| Alaska | 112,221 | 87,764 | 17,666 | 6,791 |

| American Samoa | 5,960 | 2,936 | 1,859 | 1,165 |

| Arizona | 1,468,715 | 1,194,251 | 217,692 | 56,772 |

| Arkansas | 712,122 | 507,293 | 166,133 | 38,696 |

| California | 6,251,295 | 5,164,654 | 879,247 | 207,394 |

| Colorado | 939,291 | 779,984 | 126,852 | 32,455 |

| Connecticut | 708,390 | 580,464 | 105,177 | 22,749 |

| Delaware | 234,539 | 189,898 | 36,721 | 7,920 |

| District of Columbia | 83,476 | 64,939 | 14,930 | 3,607 |

| Florida | 4,986,213 | 4,039,354 | 770,228 | 176,631 |

| Georgia | 1,945,822 | 1,466,676 | 380,095 | 99,051 |

| Guam | 19,707 | 14,489 | 3,410 | 1,808 |

| Hawai’i | 291,053 | 247,504 | 33,829 | 9,720 |

| Idaho | 385,393 | 307,704 | 62,788 | 14,901 |

| Illinois | 2,285,265 | 1,832,931 | 371,343 | 80,991 |

| Indiana | 1,401,813 | 1,072,195 | 267,646 | 61,972 |

| Iowa | 677,020 | 544,423 | 110,283 | 22,314 |

| Kansas | 580,532 | 460,610 | 95,858 | 24,064 |

| Kentucky | 1,014,477 | 720,044 | 241,548 | 52,885 |

| Louisiana | 933,612 | 679,089 | 202,023 | 52,500 |

| Maine | 363,772 | 282,480 | 68,494 | 12,798 |

| Maryland | 1,048,952 | 845,560 | 161,492 | 41,900 |

| Massachusetts | 1,306,185 | 1,042,562 | 217,073 | 46,550 |

| Michigan | 2,269,413 | 1,737,610 | 442,771 | 89,032 |

| Minnesota | 1,100,951 | 896,839 | 167,977 | 36,135 |

| Mississippi | 685,446 | 481,805 | 162,211 | 41,430 |

| Missouri | 1,341,389 | 1,013,179 | 269,158 | 59,052 |

| Montana | 253,030 | 205,256 | 38,476 | 9,298 |

| N. Mariana Islands | 3,647 | 2,329 | 796 | 522 |

| Nebraska | 364,735 | 295,842 | 55,271 | 13,622 |

| Nevada | 579,563 | 466,545 | 90,469 | 22,549 |

| New Hampshire | 326,752 | 257,757 | 56,338 | 12,657 |

| New Jersey | 1,669,244 | 1,364,085 | 247,044 | 58,115 |

| New Mexico | 461,134 | 356,772 | 82,790 | 21,572 |

| New York | 3,710,827 | 2,945,098 | 636,132 | 129,597 |

| North Carolina | 2,234,888 | 1,722,302 | 421,646 | 90,940 |

| North Dakota | 143,329 | 116,818 | 21,172 | 5,339 |

| Ohio | 2,427,966 | 1,883,359 | 447,554 | 97,053 |

| Oklahoma | 824,838 | 616,341 | 167,068 | 41,429 |

| Oregon | 917,497 | 752,638 | 138,801 | 26,058 |

| Pennsylvania | 2,898,240 | 2,288,413 | 507,130 | 102,697 |

| Puerto Rico | 824,394 | 603,228 | 193,464 | 27,702 |

| Rhode Island | 233,253 | 181,819 | 42,720 | 8,714 |

| South Carolina | 1,238,565 | 951,690 | 233,590 | 53,285 |

| South Dakota | 193,088 | 158,299 | 27,847 | 6,942 |

| Tennessee | 1,516,343 | 1,133,390 | 308,890 | 74,063 |

| Texas | 4,568,465 | 3,573,775 | 774,564 | 220,126 |

| U.S. Virgin Islands | 21,921 | 18,207 | 2,843 | 871 |

| Utah | 447,459 | 357,554 | 67,243 | 22,662 |

| Vermont | 159,575 | 126,906 | 27,265 | 5,404 |

| Virginia | 1,618,643 | 1,281,799 | 274,564 | 62,280 |

| Washington | 1,428,764 | 1,171,028 | 213,309 | 44,427 |

| West Virginia | 474,159 | 346,069 | 105,377 | 22,713 |

| Wisconsin | 1,307,526 | 1,039,858 | 225,045 | 42,623 |

| Wyoming | 123,325 | 98,896 | 19,763 | 4,666 |

| Total | 65,293,106 | 51,407,506 | 11,292,949 | 2,592,651 |

Note: Totals include residents of territories and people in the U.S. who reside abroad.

Source: Social Security Administration, Annual Statistical Supplement to the Social Security Bulletin, 2023, Table 5.J5, https://www.ssa.gov/policy/docs/statcomps/supplement/

End Notes

[1] CBPP, “Policy Basics: Top Ten Facts About Social Security,” updated April 17, 2023, https://www.cbpp.org/research/social-security/policy-basics-top-ten-facts-about-social-security.

[2] CBPP analysis of data from the U.S. Census Bureau’s March 2022 Current Population Survey.

[3] Social Security Administration (SSA), “Annual Statistical Supplement to the Social Security Bulletin,” 2022, Table 5.F4, https://www.ssa.gov/policy/docs/statcomps/supplement/.

[4] CBPP analysis of data from the U.S. Census Bureau’s March 2022 Current Population Survey.

[5] Poverty thresholds depend on the size of the family and its members’ ages; the $27,740 figure is a weighted average for families of four. For more information, see https://www.census.gov/data/tables/time-series/demo/income-poverty/historical-poverty-thresholds.html.

[6] U.S. Census Bureau, “Income, Poverty, and Health Insurance Coverage in the United States: 2021,” September 13, 2022, https://www.census.gov/newsroom/press-releases/2022/income-poverty-health-insurance-coverage.html.

[7] Eugene Smolensky, Sheldon Danziger, and Peter Gottschalk, “The Declining Significance of Age in the United States: Trends in the Well-Being of Children and the Elderly Since 1939,” in John L. Palmer, Timothy Smeeding, and Barbara Boyle Torrey, eds., The Vulnerable, Urban Institute, 1988; Gary V. Engelhardt and Jonathan Gruber, “Social Security and the Evolution of Elderly Poverty,” National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper 10466, May 2004.

[8] Adam Bee and Joshua Mitchell, “Do Older Americans Have More Income Than We Think?” U.S. Census Bureau, Social, Economic, and Housing Statistics Division Working Paper No. 2017-39, July 2017, https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/working-papers/2017/demo/SEHSD-WP2017-39.pdf.

[9] Irena Dushi and Brad Trenkamp, “Improving the Measurement of Retirement Income of the Aged Population,” SSA, Office of Research, Evaluation, and Statistics Working Paper No. 116, January 2021, https://www.ssa.gov/policy/docs/workingpapers/wp116.html.

[10] Irena Dushi, Howard M. Iams, and Brad Trenkamp, “The Importance of Social Security Benefits to the Income of the Aged Population,” Social Security Bulletin, 2017, https://www.ssa.gov/policy/docs/ssb/v77n2/v77n2p1.html.