Previewing Next Week’s Census Bureau Data on Poverty, Income, and Health Insurance

End Notes

[1] Counting both those officially unemployed and those home sick, caring for a sick relative or for a child learning remotely, or otherwise not at work because of the crisis, 61 million people were either sidelined workers or living with a family member who was, according to our analysis of the August 2020 basic monthly Current Population Survey public-use file.

[2] U.S. Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics, https://www.bls.gov; U.S. Department of Labor, Employment and Training Administration, https://oui.doleta.gov/unemploy/DataDashboard.asp.

[3] Food insecurity may have doubled overall — and tripled among households with children — in April and May 2020, according to estimates using data from the COVID Impact Survey, Current Population Survey, and other sources. Diane Schanzenbach and Abigail Pitts, “How Much Has Food Insecurity Risen? Evidence from the Census Household Pulse Survey,” Northwestern University Institute for Policy Research, June 10, 2020, https://www.ipr.northwestern.edu/documents/reports/ipr-rapid-research-reports-pulse-hh-data-10-june-2020.pdf; Diane Schanzenbach and Abigail Pitts, “Food Insecurity Triples for Families With Children During COVID-19 Pandemic,” Northwestern University Institute for Policy Research, May 13, 2020, https://www.ipr.northwestern.edu/news/2020/food-insecurity-triples-for-families-during-covid.html.

[4] Lauren Bauer, “About 14 Million Children in the US Are Not Getting Enough to Eat,” Brookings Institution, July 9, 2020, https://www.brookings.edu/blog/up-front/2020/07/09/about-14-million-children-in-the-us-are-not-getting-enough-to-eat.

[5] Census Bureau Household Pulse Survey data, Food Table 2b. Food Sufficiency for Households, in the Last 7 Days, by Selected Characteristics: United States, data collected August 19-31, 2020, https://www.census.gov/data/tables/2020/demo/hhp/hhp13.html; and Center on Budget and Policy Priorities analysis of the December 2019 Current Population Survey Food Security Supplement. Recent methodological changes to the survey mean that current Pulse data on food sufficiency are not comparable with estimates for July or earlier months.

[6] Bureau of Labor Statistics, U.S. Department of Labor, “Consumer Price Index: August 2020,” September 11, 2020, https://www.bls.gov/news.release/pdf/cpi.pdf.

[7] See, in particular, Figure 8 in CBPP, “Tracking the COVID-19 Recession’s Effects on Food, Housing, and Employment Hardships,” updated September 11, 2020, https://www.cbpp.org/research/poverty-and-inequality/tracking-the-covid-19-recessions-effects-on-food-housing-and; and National Multifamily Housing Council Rent Payment Tracker. Note that the Pulse survey changed its question regarding rental payments in August. These and other methodological changes to the survey mean that Pulse data on rent hardships are not comparable with estimates for earlier months.

[8] Arloc Sherman, “Research Note: How the Pandemic Could Skew Official Poverty Figures for 2019,” CBPP, September 8, 2020, https://www.cbpp.org/research/poverty-and-inequality/research-note-how-the-pandemic-could-skew-official-poverty-figures.

[9] Income failed to equal or surpass a previous record high in only one recovery of at least two years’ duration in the past 50 years (the recovery beginning in 2001 and ending in 2007).

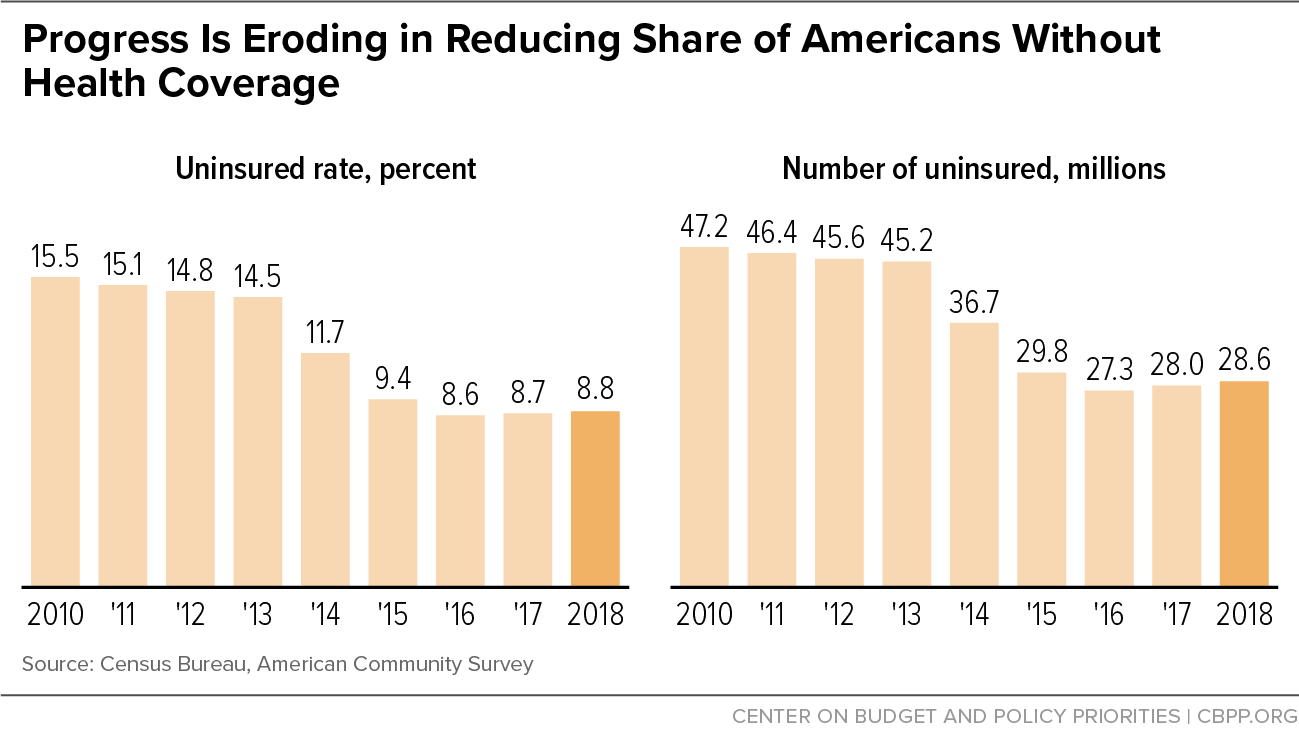

[10] In addition to being a larger survey, the ACS is a more revealing survey than the CPS for comparing uninsured rates over recent years because it has had a more consistent approach to measuring health insurance coverage. The CPS changed its methodology in both 2014 and 2018. The 2019 ACS added two new survey questions regarding some aspects of private insurance but these are not expected to significantly influence its estimates of the overall uninsured rate.

[11] Congressional Budget Office, “Federal Subsidies for People Under Age 65: 2019 to 2029,” May 2019, https://www.cbo.gov/system/files/115th-congress-2017-2018/reports/53826-healthinsurancecoverage.pdf.

[12] Jennifer Haley et al., “One in Five Adults in Immigrant Families with Children Reported Chilling Effects on Public Benefit Receipt in 2019,” Urban Institute, June 18, 2020, https://www.urban.org/research/publication/one-five-adults-immigrant-families-children-reported-chilling-effects-public-benefit-receipt-2019.

[13] Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, “Trends in Subsidized and Unsubsidized Enrollment,” August 12, 2019, https://www.cms.gov/CCIIO/Resources/Forms-Reports-and-Other-Resources/Downloads/Trends-Subsidized-Unsubsidized-Enrollment-BY17-18.pdf.

[14] Matt Broaddus, “Research Note: Medicaid Enrollment Decline Among Adults and Children Too Large to Be Explained by Falling Unemployment,” CBPP, July 17, 2019, https://www.cbpp.org/research/health/medicaid-enrollment-decline-among-adults-and-children-too-large-to-be-explained-by.

[15] Robin Cohen et al., “Health Insurance Coverage: Early Release of Estimates from the National Health Interview Survey, 2019,” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, September 2020, https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhis/earlyrelease/insur202009-508.pdf. The NHIS design and questionnaire were changed in 2019 to reduce respondent burden and increase response accuracy. Initial testing shows that even with these changes, 2019 estimates of the uninsured rate for non-elderly adults can be compared to comparable estimates from previous years.

[16] Sharon Stern, “Current Coverage, Calendar-Year Coverage: Two Measures, Two Concepts,” Census Bureau, September 10, 2019, https://www.census.gov/newsroom/blogs/research-matters/2019/09/current-coverage.html. Note: the Census Bureau in its Annual Social and Economic Supplement (ASEC) to the CPS asks survey respondents to report their health insurance coverage status both at the time of the survey and for the entirety of the previous calendar year. These questions are asked of one-quarter of February survey respondents, all March survey respondents, and one-quarter of April survey respondents. The Census Bureau’s annual health insurance coverage report highlights the previous full-year results, but the Census Bureau also typically publishes a separate research note featuring the current coverage results. The uninsured rate based on the results for a given month typically is higher than the rate that is based on having coverage over the full year, because some people have health insurance coverage for only part of the year.

[17] CBPP analysis using Medicaid administrative enrollment data from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. See https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid/program-information/medicaid-and-chip-enrollment-data/report-highlights/index.html. Also see Broaddus, 2019.

[18] In addition to the main health insurance coverage report, which will highlight CPS survey respondents’ health insurance coverage status for 2019, the Census Bureau plans to release separately on September 15 a table showing survey respondents’ health insurance status at the time of the CPS interview. Interviews were conducted in February, March, and April 2020. These estimates may capture a very small portion of the initial impact of the COVID-19 recession on the number of uninsured but will not capture the full impact as loss of health insurance coverage during a recession has been shown to lag the loss of employment.

[19] Matt Broaddus, “Medicaid Enrollment Continues to Rise,” CBPP, September 9, 2020, https://www.cbpp.org/blog/medicaid-enrollment-continues-to-rise.