Research Note: How the Pandemic Could Skew Official Poverty Figures for 2019

End Notes

[1] Bureau of Labor Statistics, “The Employment Situation — March 2020,” https://www.bls.gov/news.release/archives/empsit_04032020.pdf; Bureau of Labor Statistics, “The Employment Situation — April 2020,” https://www.bls.gov/news.release/archives/empsit_05082020.pdf.

[2] By design, the ASEC includes all CPS households in March but only about one-fourth of those in February and April. U.S. Bureau of the Census, Current Population Survey 2019 Annual Social and Economic Supplement (ASEC) Technical Documentation, p. 2-2.

[3] The monthly CPS includes a single question about approximate annual family income. This one question is not as thorough or precise as the long battery of income topics and probing follow-up questions in the ASEC questionnaire, and is not widely used by analysts, but it permits rough comparisons between groups of households. Census has not yet released the ASEC data but it released the monthly CPS data including the single income question earlier this year.

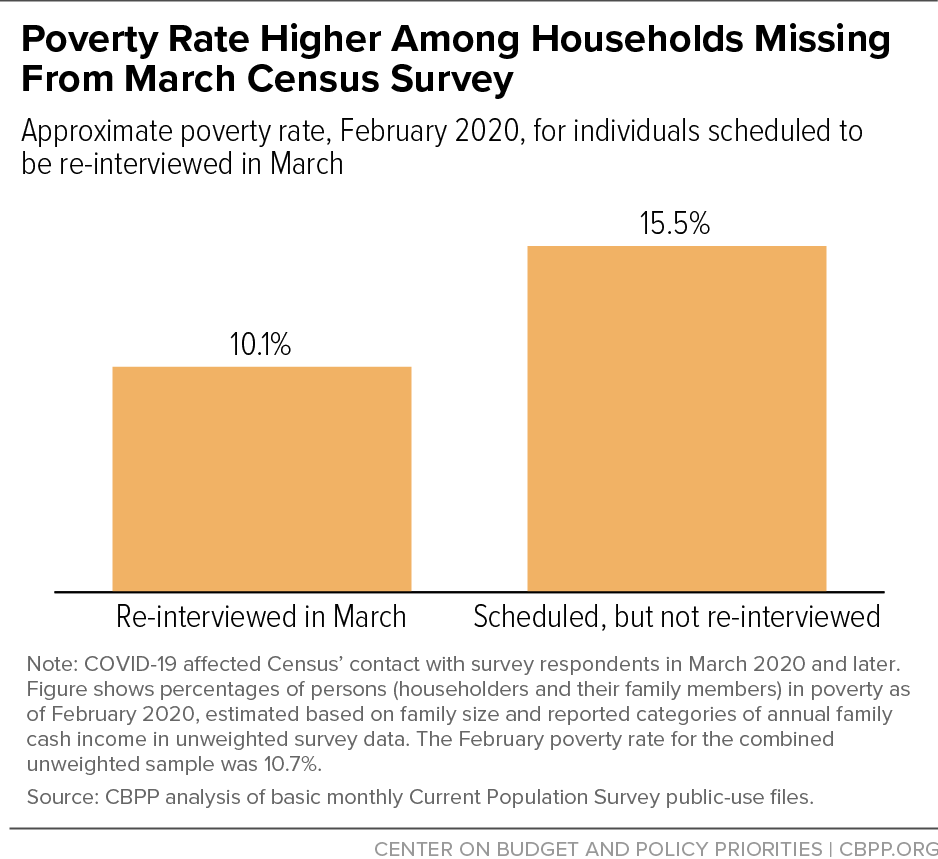

Figures in bullets use unweighted survey data so are not nationally representative.

[4] For example, Census’ preliminary weighted-average official poverty thresholds for 2019 are $13,016 for a one-person family unit and $26,167 for a family of four. Using the rough income categories in the monthly CPS, we classify a householder with no relatives as poor if their income is below $12,500 and below $25,000 for a family of four. We exclude persons not related to the householder. Although this method is rough, it yields an overall poverty rate for householders and family members of 10.7 percent in the unweighted February 2020 data, similar to the rate of 10.9 percent in the 2019 ASEC. Note that the purpose of this rough poverty calculation is not to provide an accurate prediction of poverty for 2019 but to help illustrate how far off base the official poverty rate could be because of the pandemic.

For preliminary official 2019 thresholds, see: https://www2.census.gov/programs-surveys/cps/tables/time-series/historical-poverty-thresholds/19preliminary.xls. For the 2019 ASEC, see: https://www2.census.gov/programs-surveys/cps/tables/pov-01/2019/pov01_100_1.xls.

[5] The analysis (a weighted linear regression) adjusts for several characteristics that the Census Bureau has previously considered when weighting the CPS, namely, whether an individual is Black, Hispanic, female, under age 1, ages 1-15, 16-44, 45-64, or 65 years and older, their state of residence, or whether they live in the Los Angeles metropolitan area or in New York City. The results do not appear to be sensitive to variations such as including additional race categories, other age groupings, the type of metro or non-metro residence, or interactions between these factors. For more on CPS weighting adjustments, see https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/cps/technical-documentation/methodology/weighting.html, revised August 13, 2015, and https://www.census.gov/prod/2006pubs/tp-66.pdf.

[6] The CPS and ACS have different strengths. In most years, Census guidance favors the CPS for national income and poverty statistics because it includes many additional detailed questions about income and family composition not included in the ACS, while favoring the ACS for state and local poverty data because its large size makes it less subject to random sampling error for small populations. Similarly, the ACS can be useful for telling whether relatively small changes from year to year are statistically meaningful.

The CPS income data are also slightly more up-to-date, insofar as the CPS always asks households about the past calendar year (in this case, 2019). By contrast, the ACS surveys Americans year-round and asks about their income in the past 12 months, so interviews conducted early in the “2019” ACS will refer mostly to income received in 2018, while data collected later in the year will refer mostly to 2019, yielding data that span both 2018 and 2019.

[7] Although the pandemic didn’t influence ACS data for this year, the ACS will have a different problem: Census changed its questionnaire in order to better measure income from private retirement, disability, and survivor pensions. The wording change could hinder poverty comparisons between 2018 and 2019 ACS data, particularly for the elderly. The change should have a much smaller effect on ACS trends for the non-elderly.