Understanding TANF Cost Recovery in the Child Support Program

End Notes

[1] Vicki Turetsky is an independent consultant and former Commissioner of the Office of Child Support Services (OCSS) during the Obama Administration.

[2] In order to receive child support, a child must have a parent who lives in a separate household. A “custodial parent” lives with the child most of the time and typically has the primary responsibility for the daily care. The “non-custodial parent” lives apart from the child and is responsible for paying child support to the custodial parent to help pay for the cost of raising the child. Custodial and non-custodial parents often share legal and/or physical custody and caregiving responsibilities, and some states have replaced these terms with “paying parent” and “receiving parent” or similar terms. Child support orders are based on the income of both parents in most states, and financial support is considered a shared responsibility. Both custodial and non-custodial parents are eligible for child support services. 42 U.S.C. § 654(4).

[3] Gina Azito Thompson, Diana Azevedo-McCaffrey, and Da’Shon Carr, “Increases in TANF Cash Benefit Levels Are Critical to Help Families Meet Rising Costs,” CBPP, February 2, 2023, https://www.cbpp.org/research/income-security/increases-in-tanf-cash-benefit-levels-are-critical-to-help-families-meet-0.

[4] In addition to the cost recovery process, there are other aspects of the child support program that impact TANF recipients’ experiences. These include the TANF requirement for them to participate in and cooperate with the child program, which is both a mechanism to facilitate TANF cost recovery and a policy to require TANF recipients to maximize their personal income (similar to work participation requirements). In addition, there are several policies that influence a non-custodial parent’s experience with the child support program, which can directly impact regularity of child support payments, employment, and family relationships, including unrealistically high support orders, the accumulation of unmanageable child support debt, and debt-driven enforcement mechanisms, particularly incarceration and driver’s license suspension. See Vicki Turetsky, “An Evidence-Based Approach to Child Support” toolkit, Ascend at the Aspen Institute and Good+Foundation, February 2023, https://ascend.aspeninstitute.org/an-evidence-based-approach-to-child-support/.

[5] Elaine Sorensen, “Child Support is a Good Investment,” Office of Child Support Enforcement, December 2016, https://www.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/documents/ocse/sbtn_csp_is_a_good_investment.pdf.

[6] Vicki Turetsky, “Ensuring Families Receive All Child Support Payments,” An Evidence-Based Approach to Child Support toolkit, Ascend at the Aspen Institute and Good+Foundation, February 2023, https://ascend-resources.aspeninstitute.org/resources/child-support-policy-fact-sheet-paying-support-to-families/.

[7] The federal Office of Child Support Enforcement has placed a priority of obtaining consistent support payments for families across several administrations. This emphasis on developing regular, on-time payments represents a shift away from the focus on collecting child support debt contained in the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act of 1996 (PRWORA). 81 FR 93492, “Flexibility, Modernization in Child Support Enforcement Programs,” 93492, December 20, 2016 (final rules); Office of Child Support Enforcement, “National Child Support Strategic Plan for 2015-2019,” https://www.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/documents/ocse/national_child_support_strategic_plan_2015_2019.pdf; Office of Child Support Enforcement, “National Child Support Enforcement Strategic Plan FY 2005-2009,” https://www.acf.hhs.gov/archive/css/training-technical-assistance/national-child-support-enforcement-strategic-plan-fy2005.

[8] Elizabeth Peters et al., “Legislating Love: The Effect of Child Support and Welfare Policies on Father-child Contact,” Review of Economics of the Household, Vol. 2, September 2004, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11150-004-5647-5; Virginia Knox, “The Effects of Child Support Payments on Development Outcomes for Elementary School-Age Children,” Journal of Human Resources, Vol. 31, No. 4, 1996, https://doi.org/10.2307/146148; Gerry L. White, Leon Banks, and Harold E. Briggs, “The Effects of Child Support Payment Factors on Satisfaction With Levels of Parental Involvement by Noncustodial Fathers,” Research on Social Work Practice, Vol. 31, No. 8, April 26, 2021, https://doi.org/10.1177/10497315211004744.

[9] 42 U.S.C. §§ 608(a)(2); 42 U.S.C. § 654(29).

[10] There are good cause and other exemptions defined by states, such as in the case of domestic violence. Depending on the state, good cause waivers may be granted by both the TANF and child support agencies. 42 U.S.C. § 654(29)(A); 45 C.F.R. §§ 260.51. A child support case referred by the TANF agency to the child support agency also may be closed when there is a risk of harm, or the case was inappropriately referred. 45 C.R.R. § 303.11(b)(6)(iii), (14) and (20). However, these waivers are often difficult for families to obtain. Office of Child Support Enforcement, “Domestic Violence Resources, Training, and Collaboration,” OCSE-IM-22-04, October 28, 2022,

https://www.acf.hhs.gov/css/policy-guidance/domestic-violence-resources-training-and-collaboration;

Office of Child Support Enforcement, “Model Procedures for Domestic Violence Cases,” OCSE-IM-19-06, August 21, 2019, https://www.acf.hhs.gov/css/policy-guidance/model-procedures-domestic-violence-cases. For a more detailed explanation of TANF and child support good cause waiver provisions, see Susan Notar and Vicki Turetsky, “Models for Safe Child Support Enforcement,” Journal of Gender, Social Policy & the Law, Vol. 8:3, pp. 657-716, 2000, https://digitalcommons.wcl.american.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1144&context=jgspl.

[11] 42 U.S.C. § 608(a)(3).

[12] This brief focuses on TANF cost recovery. However, separate cost recovery policies also apply to Medicaid and IV-E-funded foster care maintenance payments. Federal law requires child support cooperation by custodial parents receiving TANF, IV-E-funded foster care maintenance payments, and Medicaid, and allows states to require cooperation by custodial parents receiving SNAP. 42 U.S.C. §§ 608(a)(2); 654(29); 671(a)42 C.R.F. § 433.147; 42 U.S.C. § 671(a)(17); Children’s Bureau,” Child Welfare Policy Manual,” 8.4C; OCSE-IM-14-01, 42 C.F.R. § 433.147. Child support paid on behalf of children receiving IV-E-funded foster care maintenance payments is subject to assignment in “appropriate” cases. 42 U.S.C. § 671(a)(17). However, child support assignment to reimburse Medicaid costs is limited to medical support payments designated in a support order and does not apply to regular child support payments. 42 C.F.R. § 433.145; 45 C.F.R. §§ 302.50(e); 303.31.

[13] Rakesh Kochhar, ”The Enduring Grip of the Gender Pay Gap,” Pew Research Center, March 1, 2023, https://www.pewresearch.org/social-trends/2023/03/01/the-enduring-grip-of-the-gender-pay-gap/; Marina Zhavoronkova, Rose Khattar, Mathew Brady, ”Occupational Segregation in America,” Center for American Progress, March 29, 2022, https://www.americanprogress.org/article/occupational-segregation-in-america/.

[14] Until Congress established the national child support program under title IV-D, child support was considered a private family law matter, except for cost recovery legal actions pursued by the county attorney against the non-custodial parents of children receiving AFDC. Generally, child support was resolved as part of a divorce proceeding. At that time, most states did not have child support guidelines for establishing orders that were consistent across cases, were predictably based on the ability of a non-custodial father to pay the obligation amount, and provided for ongoing payment obligations. Non-custodial fathers of children receiving AFDC often received higher obligation amounts than better-off non-custodial fathers, who were sometimes ordered to repay AFDC benefits in full. Moderate- and high-income non-custodial fathers sometimes offered a one-time lump sum financial settlement in lieu of monthly child support payments required through the child’s minority. Once a support obligation was established, the financial burden to pursue enforcement proceedings fell to the custodial parent, while effective enforcement mechanisms were lacking. For children born to unmarried parents, the procedures for establishing a legal father were a cumbersome and costly first step in obtaining a child support order, with some states requiring jury trials to establish paternity. See Irwin Garfinkel, Daniel R. Meyer, and Sara S. McLanahan, “A Brief History of Child Support Policies in the United States,” 14-30 in Irwin Garfinkel, Sara S. McLanahan, Daniel R. Meyer, and Judith A. Seltzer, eds., Fathers Under Fire: The Revolution in Child Support Enforcement, New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation, 1998.

[15] Carmen Solomon-Fears, “The Child Support Enforcement Program: A Legislative History,” Congressional Research Service, 2016, https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/R/R44423/4; Nan D. Hunter, “Child Support Law and Policy: The Systematic Imposition of Costs on Women,” Georgetown University law Center, 1983, https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/70375619.pdf; S. Rep. No. 93-1356, 42-44, December 14, 1974 (conference report accompanying H.R. 17045, the Social Services Amendments of 1974, P.L. 93-247), https://www.fordlibrarymuseum.gov/library/document/0055/12006489.pdf; M.P. Winston and T. Forsher, “Nonsupport of Legitimate Children by Affluent Fathers as a Cause of Poverty and Welfare Dependence,” RAND Corp., 1974, https://www.rand.org/pubs/papers/P4665-1.html.

[16] William P. Quigley, “The Quicksands of The Poor Law: Poor Relief Legislation in a Growing Nation, 1970-1920,” Northern Illinois University Law Review, Vol. 18, No. 1, 1997, https://huskiecommons.lib.niu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1468&context=niulr.

[17] Daniel L. Hatcher, “Child Support Harming Children: Subordinating the Best Interests of Children to the Fiscal Interests of the State,” Wake Forest Law Review, Vol. 42, pp. 1029-1086,

https://deliverypdf.ssrn.com/delivery.php?ID=458117106069068080116099085104080118051053051021058043068126072104101115011076093102036054032126054012052114026027095101078013038007053017081068020113012029092076059059048092110101004005107084028070114095121124085070021103127120121112100078066121003&EXT=pdf&INDEX=TRUE; Larry Cata Backer, “Medieval Poor Law in Twentieth Century America: Looking Back Towards a General Theory of Modern American Poor Relief,” Case Western Reserve Law Review, Vol. 44(3), 1994, https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2675&context=caselrev; David C. Baldus, “Welfare as a Loan: An Empirical Study of the Recovery of Public Assistance Payments in the United States,” Stanford Law Review, Vol. 25(2), pp. 123-250 (1973),https://www.jstor.org/stable/1227967; Thomas A. Wadden, Jr., “Note: Criminal Law—North Carolina Bastardy Statute—Support of Illegitimate Children,” North Carolina Law Review, Vol. 26(3), pp. 305-309; 1948,

https://scholarship.law.unc.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?referer=&httpsredir=1&article=5562&context=nclr; W. Logan MacCoy, Law of Pennsylvania Relating to Illegitimacy, Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology, Vol. 7(4), 1917, https://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1473&context=jclc; W.R. Vance, “The Parent’s Liability for Necessaries Furnished for His Minor Child,” Virginia Law Register, Vol. VI(9), 1901, https://www.jstor.org/stable/1098948.

[18] Under common law, fathers had the duty to support their children, although private child support payment laws did not come into general effect until the late nineteenth century. Third-party creditors, including counties, providing “necessaries” to children and their mothers could sue fathers for reimbursement. In the 19th century, counties established poor houses and county work farms as a form of poor relief. Indigent adults and children born to unmarried parents who were committed to the county’s custody could be “bound out” for their labor. For a discussion of the racialized application of bastardy laws, see Kaaryn Gustafson, “On the History and Impact of Bastardy Laws” (podcast), Irvine School of Law, University of California, https://www.law.uci.edu/podcast/episode4.html.

[19] In 1980, states were authorized to receive federal funding to provide child support services to custodial families who did not receive AFDC. In 1984, states were required to provide equal services to non-AFDC families. Congressional Research Service, The Child Support Enforcement Program: A Legislative History, 2016,

https://www.everycrsreport.com/files/20160321_R44423_7c7c042b8038f53dcc732fb77538a7924e1cfe14.pdf; Committee On Ways And Means, United States House of Representatives, “Child Support Enforcement Legislative History,” 2012, https://greenbook-waysandmeans.house.gov/2012-green-book/child-support-enforcement-cover-page/legislative-history.

[20] Custodial parents are not required to participate in the child support program once they stop receiving TANF assistance. However, they may continue receiving services without filing an application or paying fees. Even if they decide to terminate child support services, the support owed during the assistance period remains permanently assigned to the state, and an “arrears-only” case remains open until the state has collected assigned arrears, writes off the assigned debt, or closes the case under limited case closure rules. 42 U.S.C. §§ 654(6)(B); 45 C.F.R. § 302.33(a); 303.11.

[21] According to 2018 Current Population Survey-Child Support Supplement data (CPS-CSS) conducted by the U.S. Census Bureau, 62 percent of custodial parents participate in the program, while 38 percent do not. Elaine Sorensen, “Characteristics of Custodial Parents and Their Children,” Office of Child Support Enforcement, 2021,

https://www.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/documents/ocse/characteristics_cps_and_their_children.pdf.

[22] According to 2018 CPS-CSS data, 61 percent of children in custodial families receiving child support services have incomes below 200 percent of the federal poverty level, compared to 23 percent of children in custodial families receiving child support services with incomes at or above 300 percent of the poverty level. Among children in custodial families who are eligible for child support services but are not receiving them, 49 percent have incomes below 200 percent of poverty, compared to 35 percent with incomes at or above 300 percent of the poverty level. Sorensen, 2021, op. cit.

[23] 45 C.F.R. §§ 303.8; 302.33(a)(6).

[24] 45 C.F.R. § 303.56(c). See Vicki Turetsky, “Setting Realistic and Accurate Child Support Orders,” An Evidence-Based Approach to Child Support toolkit, Ascend at the Aspen Institute and Good+Foundation, February 2023,

https://ascend-resources.aspeninstitute.org/resources/setting-realistic-and-accurate-child-support-orders/.

[25] Office of Child Support Enforcement, “Preliminary Report FY 2022,” Table P-89, https://www.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/documents/ocse/fy_2022_preliminary_report.pdf.

[26] Daniel R. Meyer and Quentin H. Riser, “Slowing the ‘vicious cycle’: Reducing the interest rate on child support arrears,” Children and Youth Services Review, Vol. 144, January 2023, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0190740922003486; Jessica Pearson and Rachel Wildfeuer, “Policies and Programs Affecting Fathers: A State-by-State Report,” Fatherhood Research & Practice Network, 2022, https://www.frpn.org/asset/policies-and-programs-affecting-fathers-state-state-report-combined-pdf.

[27] 42 U.S.C. § 654(6); 45 C.F.R. § 302.33 (c), (d), and (e).

[28] Because states do not owe a federal share on assigned support until it is collected, they do not incur a financial obligation to the federal government if they write off uncollected state debt. Office of Child Support Enforcement, “Family and State Benefits of Debt Compromise,” OCSE-IM-22-03, August 18, 2022, https://www.acf.hhs.gov/css/policy-guidance/family-and-state-benefits-debt-compromise; Office of Child Support Enforcement, “State Program Flexibility with Respect to Low-Income Obligors,” OCSE-AT-03, September 14, 2000. For information on state child support debt reduction policies, see Vicki Turetsky, “Implementing Sensible Debt Reduction Strategies,” An Evidence-Based Approach to Child Support toolkit, Ascend at Aspen Institute and Good+Foundation, Rev. Feb. 2023, https://ascend.aspeninstitute.org/an-evidence-based-approach-to-child-support/; Office of State Child Support Enforcement, “State Child Support Agencies with Debt Compromise Policies” (undated) (state-by-state), https://www.acf.hhs.gov/css/map/state-child-support-agencies-debt-compromise-policies; Office of Child Support Enforcement, “State Program Flexibility with Respect to Low-Income Obligors,” OCSE-AT-03, September 14, 2000.

[29] 42 U.S.C. § 664; 666; 45 C.F.R. § 302.60. Federal law exempts SSI, and many state exempt certain means-tested benefits. 45 C.F.R. § 307.11.

[30] 42 U.S.C. § 666(a)(1) and (b).

[31] 42 U.S.C. § 666(b).

[32] 42 U.S.C. §§ 654; 666(a).

[33] 42 U.S.C. § 654B.

[34] 42 U.S.C. §657(c). Like Medicaid, AFDC was funded through federal matching funds based on the state’s FMAP rate. Even though TANF is funded through a federal block grant, rather than matching funds based on the FMAP, the child support program continues to use the FMAP to calculate the federal share of assigned child support.

[35] Normally, states overall keep 44 percent and the federal government receives 56 percent of collections retained as assistance reimbursement, although each state’s FMAP varies. However, in federal fiscal year 2022, states overall kept 37 percent and the federal government received 63 percent of assistance reimbursement. Office of Child Support Enforcement, “Preliminary Data Report FY 2022,” Tables P-1, P-14, and P-15. This is because Congress temporarily increased the FMAP in response to the COVID-19 pandemic as part of the Families First Coronavirus Response Act (FFCRA), P.L. No. 116-127 (signed into law on March 31, 2020), as amended by the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act (CARES Act), P.L. 116-136 (signed into law on March 27, 2020). Enhanced rates apply to the federal share of retained support collected between 2020 and 2023, meaning that states are required to send back a higher percentage of retained collections to the federal government during this period. An enhanced FMAP was in effect in 2020, 2021, and 2022, with the rate gradually decreasing during 2023 and ending on Jan. 1, 2024 (so that a higher FMAP will apply the first quarter of federal fiscal year 2024 and the regular rate will apply for the remaining three quarters). In 2022, 31 states, including the District of Columbia, had rates at or above 70 percent because the FFCRA enhanced rates were in effect. in federal fiscal year 2024, states with a regular FMAP at or above 70 percent include Alabama, Arkansas, District of Columbia, Kentucky, Mississippi, New Mexico, and West Virginia. Additional states will have an adjusted FMAP at or above 70 percent in 2024 because the first quarter of 2024 will be calculated at a higher rate. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, “Federal Financial Participation in State Assistance Expenditures; Federal Matching Shares for Medicaid, the Children's Health Insurance Program, and Aid to Needy Aged, Blind, or Disabled Persons for October 1, 2023 Through September 30, 2024,” 87 FR 74429, December 5, 2022, https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2022/12/05/2022-26390/federal-financial-participation-in-state-assistance-expenditures-federal-matching-shares-for; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, “Federal Financial Participation in State Assistance Expenditures; Federal Matching Shares for Medicaid, the Children's Health Insurance Program, and Aid to Needy Aged, Blind, or Disabled Persons for October 1, 2021 Through September 30, 2022,” 85 FR 76586, November 30, 2020, https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2020/11/30/2020-26387/federal-financial-participation-in-state-assistance-expenditures-federal-matching-shares-for; OCSS, Frequently Asked Questions For Child Support Programs (as of Feb. 10, 2021), https://www.acf.hhs.gov/css/covid-19-faqs-child-support-programs.

[36] States also distribute support payments among multiple families of a non-custodial parent. See, e.g., Maria Cancian, Daniel R. Meyer, and Steven Cook, Changes in the Incidence of Complex Families and the Implications for Child Support Orders, Institute for Research on Poverty, University of Wisconsin-Madison, 2017 and earlier related studies,

https://www.irp.wisc.edu/resource/changes-in-the-incidence-of-complex-families-and-the-implications-for-child-support-orders/.

[37] Assignment is a TANF eligibility requirement under title IV-A. 42 U.S.C. § 608(a)(3).

[38] Federal law does not authorize the use of the IV-D funded child support program resources to reimburse SNAP, child care, or other public assistance benefits, including state-funded cash assistance, except for TANF, IV-E-funded Foster Care Maintenance Payments, and Medicaid. 45 C.F.R. § 302.38; Office of Family Assistance and Office of Child Support Enforcement, “Questions and Responses on Coordination Between the TANF and the Child Support Enforcement Program,” TANF-ACF-ACF-PI-2007-02 and OCSE-AT-2007-02, May 18, 2007, https://www.acf.hhs.gov/css/policy-guidance/coordination-between-tanf-and-cse-programs-deficit-reduction-act-2005; Office of Child Support Enforcement, “Referrals, Location, Applications, and Electronic Interface Between Child Welfare and Child Support,” OCSE-IM-07-06, September 10, 2007, https://www.acf.hhs.gov/css/policy-guidance/referrals-location-applications-and-electronic-interface-between-child-welfare.

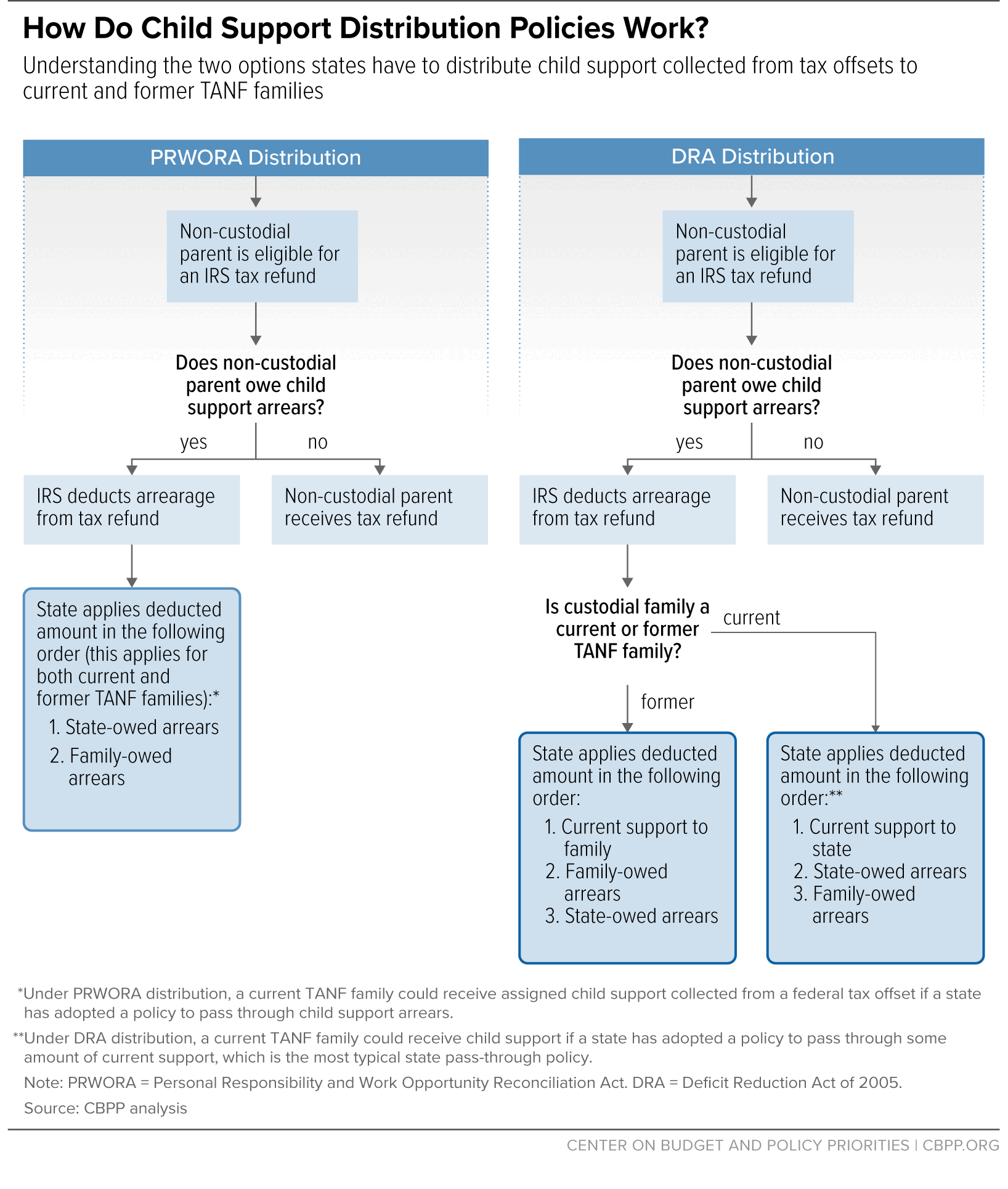

[39] During-assistance assignments are considered “permanent,” that is, state claims to support owed during the assistance period remain in effect after families leave TANF. Before PRWORA, pre-assistance assignments were also permanent. PRWORA limited the legal effect of pre-assistance assignments, making them “temporary” during the assistance period and “conditional” after the assistance period. As long as families were receiving TANF, states could keep support collections owed both before and during the assistance period. However, once families left TANF, the right to keep support owed before the assistance period reverted to the families, with one condition. The condition was that states could claim pre-assistance support collected through federal tax offsets. The DRA prospectively eliminated pre-assistance assignments altogether, eliminating “temporary” and “conditional” assignments. This means that under existing law, states may only claim support owed during the assistance period except in those older cases with pre-assistance assignments entered into before the DRA was enacted. For example, although this situation is not typical, if a family stopped receiving TANF but later reapplied for assistance, the support owed between the two assistance periods was treated as pre-assistance support and was covered by the new “pre-assistance” assignment. Even if the family had been receiving child support during the interim, the right to the support temporarily reverted to the state during the second assistance period and remained “conditionally” assigned, so that even after the second assistance period ended, a state could retain support collected through a federal tax offset.

For a more detailed explanation of PRWORA rules, see Vicki Turetsky, “In Everybody’s Best Interests: Why Reforming Child Support Distribution Makes Sense for Government and Families,” Center for Law and Social Policy (CLASP), 2005, https://www.clasp.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/0241.pdf. For a description of DRA rules, see Paul Legler and Vicki Turetsky, “More Child Support Dollars to Kids: Using New Flexibility in Child Support Pass-Through and Distribution Rules to Benefit Government and Families,” CLASP and Policy Studies, Inc., 2006,

https://www.clasp.org/publications/report/brief/more-child-support-dollars-kids-using-new-state-flexibility-child-support/.

[40] For example, a non-custodial parent might owe $5,000 in arrears at the time the custodial parent applies for TANF. Before the DRA, the custodial parent was required to assign all rights to support, including the $5,000 in arrears owed before the assistance period (called “pre-assistance assignment”) and the $2,000 in additional support owed during the assistance period (called “during-assistance assignment”). If the custodial family then received $4,000 in TANF payments, the state could retain up to $4,000, including $2,000 in support due during the assistance period plus $2,000 in support owed before the assistance period. Although the non-custodial parent owed $7,000 in assigned pre-assistance and during-assistance arrears, the state can only keep up to the amount of assistance paid out, or $4,000.

[41] The DRA also provided states with an option to implement the changed assignment rules a year early, on October 1, 2008.

[42] 42 U.S.C. § 657(b)(1) and (2); Office of Child Support Enforcement, “Assignment and Distribution of Child Support Under Sections 408(a)(3) and 457 of the Social Security Act,” OCSE-AT-07-05, July 11, 2007, https://www.acf.hhs.gov/css/policy-guidance/assignment-and-distribution-child-support-under-sections-408a3-and-457-social. https://www.acf.hhs.gov/css/policy-guidance/assignment-and-distribution-child-support-under-sections-408a3-and-457-social.

[43] Office of Child Support Enforcement, “Assignment and Distribution of Child Support Under Sections 408(a)(3) and 457 of the Social Security Act,” OCSE-AT-07-05, July 11, 2007, https://www.acf.hhs.gov/css/policy-guidance/assignment-and-distribution-child-support-under-sections-408a3-and-457-social.

[44] Office of Child Support Enforcement, “Definition of ‘Assistance Paid to the Family’ for Child Support Enforcement Collection Purposes,” OCSE-AT-99-10, September 15, 1999,

https://www.acf.hhs.gov/css/policy-guidance/definition-assistance-paid-family-child-support-enforcement-collection-purposes; Office of Child Support Enforcement, “Assignment and Distribution of Child Support Under Sections 408(a)(3) and 457 of the Social Security Act,” OCSE-AT-07-05, July 11, 2007, https://www.acf.hhs.gov/css/policy-guidance/assignment-and-distribution-child-support-under-sections-408a3-and-457-social.

[45] At the end of the assistance period, the URA balance is reconciled with the cumulative amount of child support retained by the state to determine whether any remaining support is due to the family. While the amounts of assistance paid to families and the amounts of child support kept by states to reimburse assistance are separately accounted for, the balances are reconciled only after a custodial family leaves TANF, rather than reconciled month by month, as was the case in AFDC. 42 U.S.C. § 608(a)(3); Office of Child Support Enforcement, “Definition of “Assistance Paid to the Family” for Child Support Enforcement Collection Purposes, OCSE-AT-99-10, September 15, 1999,

https://www.acf.hhs.gov/css/policy-guidance/instructions-distribution-child-support-definition-assistance-paid-family); Office of Child Support Enforcement, “Instructions for the Distribution of Child Support, Definition of Assistance Paid to the Family,” OCSE-AT-98-24, August 19, 1998,

https://www.acf.hhs.gov/css/policy-guidance/instructions-distribution-child-support-definition-assistance-paid-family; Office of Child Support Enforcement, “Instructions for the Distribution of Child Support Under Section 457 of the Social Security Act,” OCSE-AT-97-17, October 21, 1997, https://www.acf.hhs.gov/css/policy-guidance/instructions-distribution-child-support-under-section-457-social-security-act.

[46] Office of Child Support Enforcement, “Assignment and Distribution of Child Support Under Sections 408(a)(3) and 457 of the Social Security Act,” OCSE-AT-07-05, July 11, 2007,

https://www.acf.hhs.gov/css/policy-guidance/assignment-and-distribution-child-support-under-sections-408a3-and-457-social; Office of Child Support Enforcement, “Instructions for the Distribution of Child Support Under Section 457 of the Social Security Act,” OCSE-AT-97-17, October 21, 1997, https://www.acf.hhs.gov/css/policy-guidance/instructions-distribution-child-support-under-section-457-social-security-act.

[47] Distribution rules are included in title IV-D of the Social Security Act. 42 U.S.C. § 657 determines whether a collection will be applied to the state or family claims. Office of Child Support Enforcement, “Assignment and Distribution of Child Support Under Sections 408(a)(3) and 457 of the Social Security Act,” OCSE-AT-07-05, July 11, 2007, https://www.acf.hhs.gov/css/policy-guidance/assignment-and-distribution-child-support-under-sections-408a3-and-457-social.

[48] Separate distribution issues are raised in allocating support when the non-custodial parent has more than one support order, which are not discussed in this paper.

[49] 42 U.S.C. § 654(34); Office of Child Support Enforcement, “Assignment and Distribution of Child Support Under Sections 408(a)(3) and 457 of the Social Security Act,” OCSE-AT-07-05, July 11, 2007, https://www.acf.hhs.gov/css/policy-guidance/assignment-and-distribution-child-support-under-sections-408a3-and-457-social.

[50] 42 U.S.C. § 657(a); Office of Child Support Enforcement, “Instructions for the Distribution of Child Support, Definition of Assistance Paid to the Family,” OCSE-AT-98-24, August 19, 1998,

https://www.acf.hhs.gov/css/policy-guidance/instructions-distribution-child-support-definition-assistance-paid-family (Definition of Assistance Paid to the Family was superseded by “Definition of ‘Assistance Period to the Family” for Child Support Enforcement Collection Purposes, OCSE-AT-99-10, September 15, 1999,

https://www.acf.hhs.gov/css/policy-guidance/instructions-distribution-child-support-definition-assistance-paid-family); Office of Child Support Enforcement, “Instructions for the Distribution of Child Support Under Section 457 of the Social Security Act,” OCSE-AT-97-17, October 21, 1997, https://www.acf.hhs.gov/css/policy-guidance/instructions-distribution-child-support-under-section-457-social-security-act.

[51] The PRWORA tax offset exception originally codified in 42 U.S.C. § 657(a) was superseded by the language in the DRA, which eliminated the exception but allowed states to elect continuing PRWORA distribution rules. The only statutory reference to PRWORA distribution is 42 U.S.C. § 654(34), the state plan election provision.

[52] 42 U.S.C. § 654(34).

[53] Alaska, California, Maryland, New Mexico, Pennsylvania, Vermont, West Virginia, Wyoming, and Puerto Rico have adopted DRA distribution while the remaining states and Washington D.C. have PRWORA distribution.

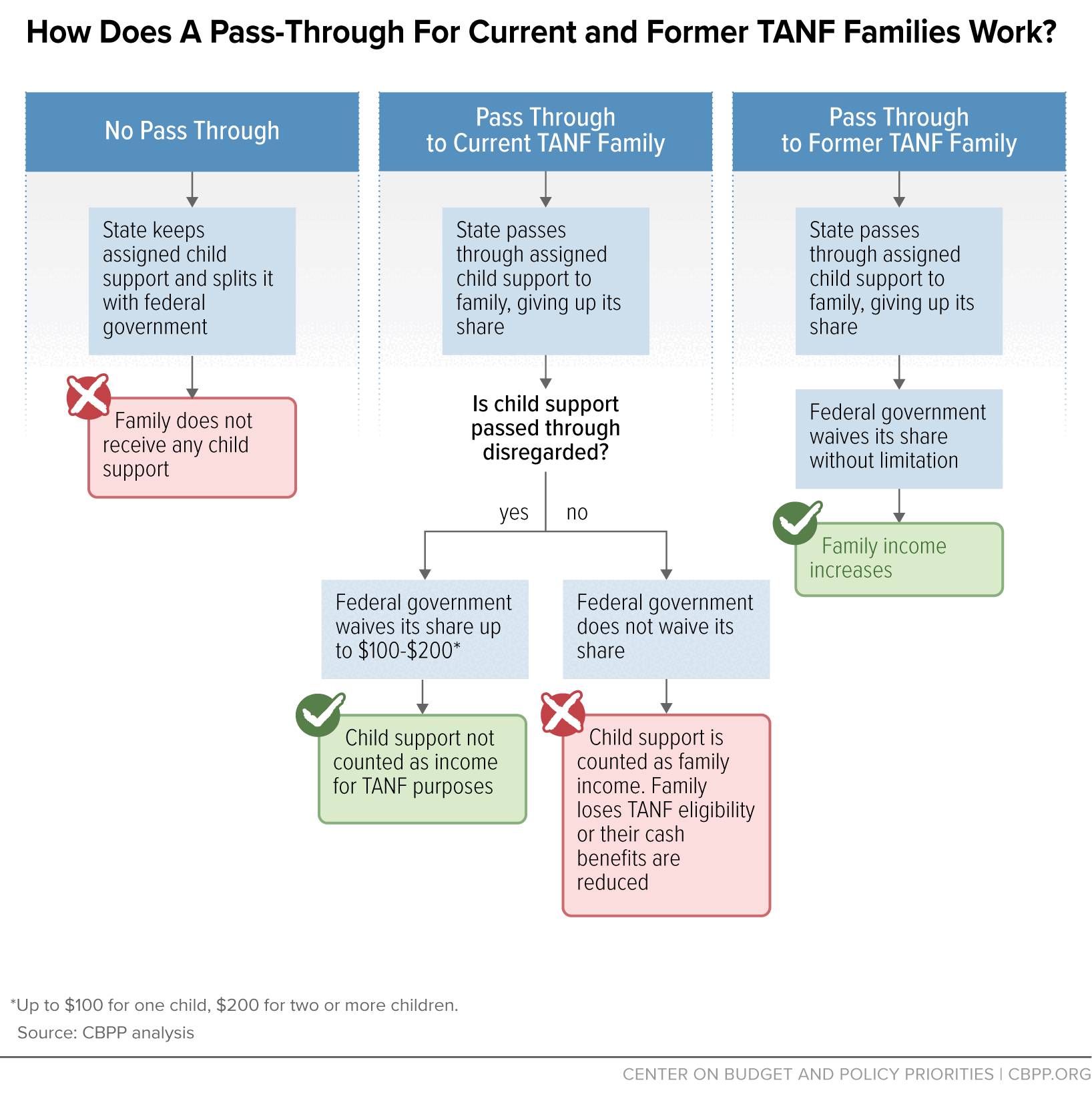

[54] 42 U.S.C. § 657(a)(1). States reported that they passed through 16 percent of current assistance collections in fiscal year 2022. In addition, states collect “excess payments” during the TANF assistance period, which states are not allowed to keep. Excess payments represent an additional 17 percent of current assistance collections. These excess payments are distributed to families receiving TANF and counted as income in the TANF program, or used to meet the day-to-day needs of children receiving IV-E funded foster care maintenance payments (rather than used as reimbursement.)

[55] Office of Child Support Enforcement, “Preliminary Report FY 2022,” Tables P-1, P-4, P-7,

https://www.acf.hhs.gov/css/policy-guidance/fy-2022-preliminary-data-report-and-tables.

[56] 42 U.S.C. § 657(a)(6)(B)(i)(III); Office of Child Support Enforcement, “Assignment and Distribution of Child Support Under Sections 408(a)(3) and 457 of the Social Security Act,” OCSE-AT-07-05, July 11, 2007,

https://www.acf.hhs.gov/css/policy-guidance/assignment-and-distribution-child-support-under-sections-408a3-and-457-social.

[57] Office of Child Support Enforcement, Instructions for the Distribution of Child Support Under Section 457 of the Social Security Act (October 21, 1997), OCSE-AT-97-17, July 11, 2007.

[58] Office of Child Support Enforcement, “Assignment and Distribution of Child Support Under Sections 408(a)(3) and 457 of the Social Security Act,” OCSE-AT-07-05, July 11, 2007, https://www.acf.hhs.gov/css/policy-guidance/assignment-and-distribution-child-support-under-sections-408a3-and-457-social. Each year, states are required to meet a maintenance-of-effort obligation under the TANF block grant or face a fiscal penalty. (The statute refers to this spending as “qualified state expenditures” but common usage is “state MOE.”) Each state’s MOE amount is based on its historical spending, defined as its 1994 financial contribution to AFDC and related work programs. To meet its MOE obligation, a state must report spending at least 80 percent of this historical spending level; this minimum share falls to 75 percent for any year in which a state meets its TANF work participation rate requirement; Aditi Shrivastava, “Policy Brief: To Strengthen Economic Security and Advance Equity, States Should Invest More TANF Dollars in Basic Assistance,” CBPP, March 8, 2023, https://www.cbpp.org/research/income-security/to-strengthen-economic-security-and-advance-equity-states-should-invest.

[59] Delaware, Georgia, Maine, South Carolina, and Tennessee elected to carry over fill-the-gap budgeting into their TANF programs that was in effect before PRWORA under a grandfather clause contained in 42 U.S.C. § 657(d). Additional states may not adopt fill-the-gap distribution in current assistance cases. In fill-the-gap budgeting, states set a TANF standard of need but a lower TANF benefit payment level. The state then fills the resulting “gap” between need and payment levels with child support or other income such as earnings. In fill-the-gap states, child support is distributed, rather than passed through, to families currently receiving TANF. In addition, two states (Delaware and Maine) pass through up to an additional $50 per month to TANF families. Office of Child Support Enforcement, Instructions for the Distribution of Child Support Under Section 457 of the Social Security Act, July 11, 2007, OCSE-AT-97-17,

https://www.acf.hhs.gov/css/policy-guidance/instructions-distribution-child-support-under-section-457-social-security-act.

[60]Although custodial families who participate in Medicaid are required to assign to the state medical support paid under a separately designated medical support order, Medicaid families may choose to collect regular cash child support payments through the child support program, and the collected child support is paid to the families and not assigned to the state. In 2022, states collected and distributed $9.4 billion in regular cash support to families receiving Medicaid. States also collected $648 million in designated medical support, some of which was distributed to families to pay for children’s health care needs, and some of which was distributed to the Medicaid program as reimbursement. Office of Child Support Enforcement, “Preliminary Report FY 2022,” Table P-2, P-52, P-55, P-56, and P-57,

https://www.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/documents/ocse/fy_2022_preliminary_report.pdf.

[61] Office of Child Support Enforcement, “Preliminary Report FY 2022,” Table P-2, P-52, P-55, P-56, and P-57,

https://www.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/documents/ocse/fy_2022_preliminary_report.pdf.

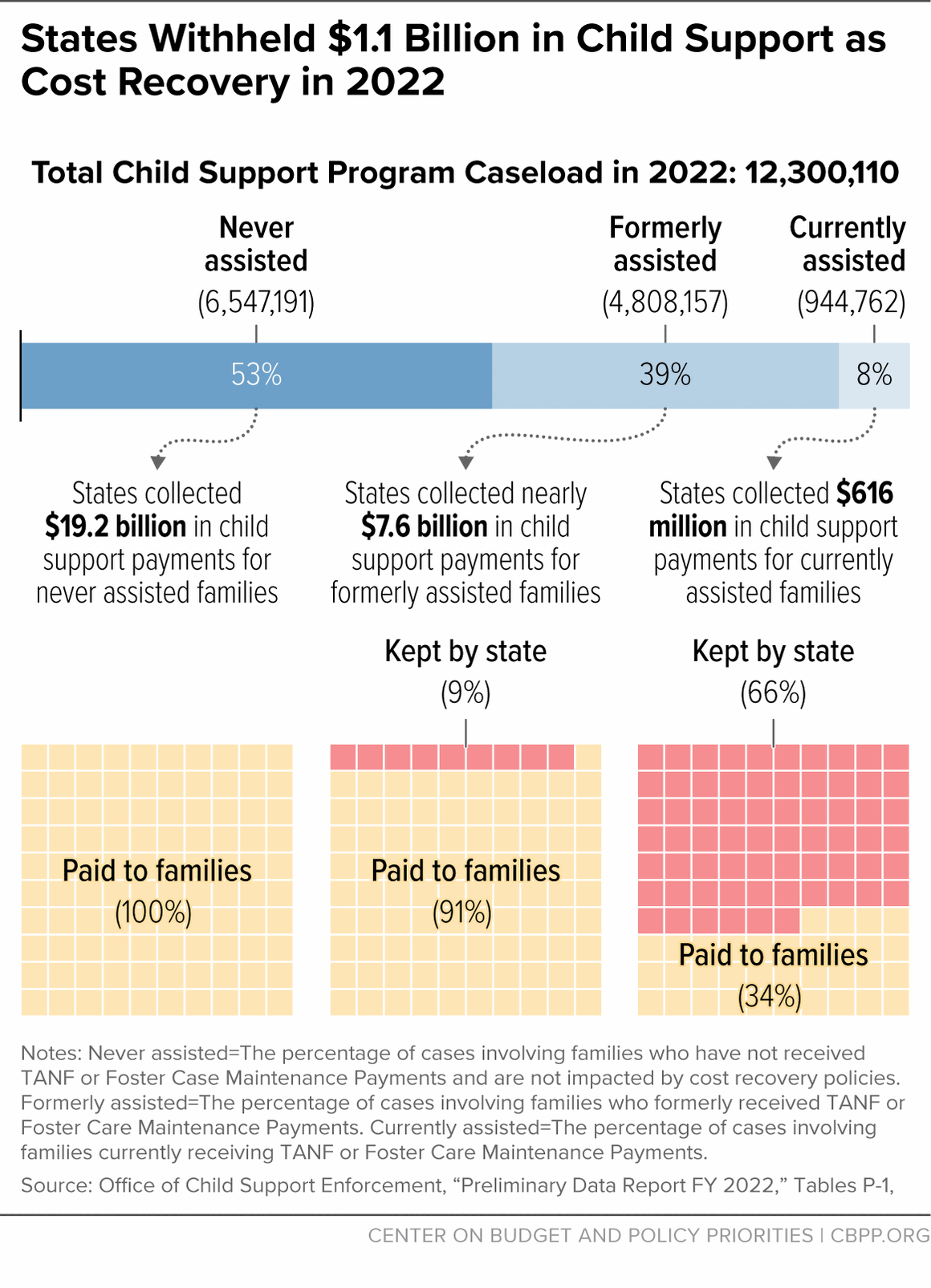

[62] Sixty-eight percent of total program collections were made on behalf of families who never received assistance, while 30 percent were made on behalf of families who formerly received assistance; just 2 percent were made on behalf of families currently receiving assistance. Office of Child Support Enforcement, “Preliminary Data Report FY 2022,” Tables P-1, https://www.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/documents/ocse/fy_2022_preliminary_report.pdf.

[63] The child support program collected $27.4 billion in fiscal year 2022. 70 percent, or $19.2 billion, were paid to families who never received assistance. (More than half of these never-assistance collections were paid to families receiving Medicaid, but not cash assistance.) The program collected $616 million on behalf of current assistance families and $7.6 billion on behalf of former assistance families. Office of Child Support Enforcement, “Preliminary Data Report FY 2022,“ Tables P-1, P-4, P-6, P-7, P-8, and P-9, https://www.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/documents/ocse/fy_2022_preliminary_report.pdf.; In addition, nearly all collections not kept to reimburse assistance are paid to families or foster care agencies and used for the day-to-day needs of the children for whom the support was collected. In current assistance cases, 65.6 percent of collections are kept as assistance reimbursement, 17.3 percent are distributed to families or foster care agencies and used for children’s needs, 15.6 percent are passed through to families, and 1.5 percent are medical support collections. In former assistance cases, 8.8 percent are kept as assistance reimbursement, 89.2 percent are distributed to families or foster care agencies and used for children’s needs, 0.1 percent are passed through to families, and 1.9 percent are medical support collections. Most medical support collections are distributed to families, but some are kept to reimburse Medicaid costs. A negligible amount of collections in current and former IV-E foster care cases are kept as fees. Office of Child Support Enforcement, Preliminary Data Report FY 2022, table P-1, https://www.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/documents/ocse/fy_2022_preliminary_report.pdf.

[64] Office of Child Support Enforcement, “Preliminary Data Report FY 2022,” Table P-1, P-2, P-52, P-55, P-56, and P-57, https://www.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/documents/ocse/fy_2022_preliminary_report.pdf.

[65] Fiscal years 2020 and 2021 were atypical collection years. Collections increased substantially due to IRS tax offsets of the first round of COVID-19 individual economic recovery payments included in the CARES Act. Subsequent payments were exempted from child support tax offsets by the American Rescue Plan Act of 2021 (ARPA), P.L. 117-2 (signed into law on March 11, 2021).

[66] Shrivastava, op. cit.