Housing mobility programs help low-income families with children use Housing Choice Vouchers to move to high-opportunity neighborhoods. These neighborhoods often have less poverty, better schools, less crime, and more resources such as grocery stores and parks, which together promote better health and life satisfaction for parents and children and improve children’s chances of succeeding in school and earning more as adults. Evidence suggests many low-income families would like to move to high-opportunity communities, but barriers — including high housing costs, discrimination, and a shortage of willing landlords — often prevent them from doing so.[1] Mobility programs give families more choices about where they can live, which is an important complement to investing in historically disadvantaged communities to create new opportunities for residents.

Mobility programs help families use Housing Choice Vouchers (HCVs) to access high-opportunity neighborhoods through:

- services such as housing search assistance, informative briefings about neighborhoods and their potential impacts on children, and landlord recruitment in high-opportunity areas;

- short-term financial assistance to help with moving costs such as rental application fees or security deposits; and

- administrative policies such as basing housing subsidies on more accurate local market rents and providing families adequate time to search for housing.

A recent Harvard study found that a Seattle mobility program was highly effective: low-income families offered comprehensive housing mobility services were 40 percentage points more likely to move to high-opportunity neighborhoods than similar families that did not receive assistance.[2] This rigorous evidence makes a strong case that mobility programs are worth federal investment, both to expand their availability to more families and to continue to improve their design and implementation.

Children’s development and their chances of growing up to be healthy, productive adults are significantly influenced by where they live, that is, by the quality of the schools, the safety of the streets and playgrounds, and many other characteristics. Research shows that severely disadvantaged areas with under-performing schools and high rates of violent crime can undermine children’s development and chances of success, while enabling low-income families to move to lower-poverty neighborhoods can have substantial positive effects on children’s long-term outcomes.[3] For instance, a seminal 2015 study by Harvard economists Raj Chetty, Nathaniel Hendren, and Lawrence Katz found that young children in low-income families using housing vouchers to move from public housing in extremely poor neighborhoods to lower-poverty neighborhoods were much more likely to attend college and earned more as young adults than similar children whose families did not have this option.[4] Moreover, the effects were cumulative: the longer children lived in lower-poverty neighborhoods, the larger their gains as young adults.

This evidence has persuaded policymakers and other stakeholders to begin lowering families’ barriers to living in high-opportunity areas. For instance, the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) now allows, and in some communities requires, housing agencies to set voucher subsidies in relation to local (rather than metro-area) rents, which expands families’ housing options by increasing voucher payments in higher-rent neighborhoods.[5] Some housing agencies have also modified their policies to give families more time to search for housing. But much more must be done to improve families’ access to high-opportunity communities (see below).

Mobility programs can also mitigate the effects of decades of housing policies and practices that have limited some people’s housing options and contributed to the over-representation of people of color — particularly Black Americans — in high-poverty, low-opportunity neighborhoods that have suffered underinvestment.[6] Policymakers and courts have taken some steps to reverse this trend; mobility programs provide housing agencies with an important tool to advance this goal further.

The 1968 Fair Housing Act prohibited housing discrimination on the basis of race and other protected characteristics and directed that federal programs and activities “affirmatively further fair housing” — that is, operate in ways that “undo historic patterns of segregation and other types of discrimination and afford access to opportunity that has long been denied.”[7] In 1974 federal policymakers created a new tenant-based rental assistance program, now known as Housing Choice Vouchers, enabling families to choose the units they wanted to rent in the private market. While this market-based approach was intended to provide families with greater housing choice, state and local housing agencies typically did not provide families with assistance in finding rentals, and they did not consider neighborhood outcomes important.[8]

This framework began to change following court actions enforcing agencies’ obligations to affirmatively further fair housing. In particular, the settlement agreements in the landmark public housing desegregation cases Gautreaux v HUD in Chicago and Walker v. HUD in Dallas relied on rental vouchers combined with housing mobility services to enable families of color to live in low-poverty communities from which they had been traditionally excluded.[9] In the 1990s, policymakers also began to take an interest in the potential role of the housing voucher program in reducing segregation and expanding families’ access to opportunity. Congress authorized the Moving to Opportunity demonstration, a rigorous five-city study of low-income families that received housing vouchers to help them move from public housing in extremely poor areas to lower-poverty neighborhoods. Its success in helping families move to these lower-poverty communities, and the long-term gains that the young children in these families experienced (as Chetty and his colleagues documented), have affirmed the benefits of housing vouchers as a tool to mitigate segregation and its harmful effects.

While evidence suggests that many families would like to use their vouchers to rent housing in high-opportunity areas, they must often overcome many barriers to do so.[10] Less than 2 percent of local public housing agencies provide services to help families use their vouchers in high-opportunity areas.[11] (The mobility programs that exist are typically funded from special time-limited public or private grants.) As a result, only a small share of families with children using vouchers live in high-opportunity neighborhoods, even though voucher-affordable units are often available in these neighborhoods.

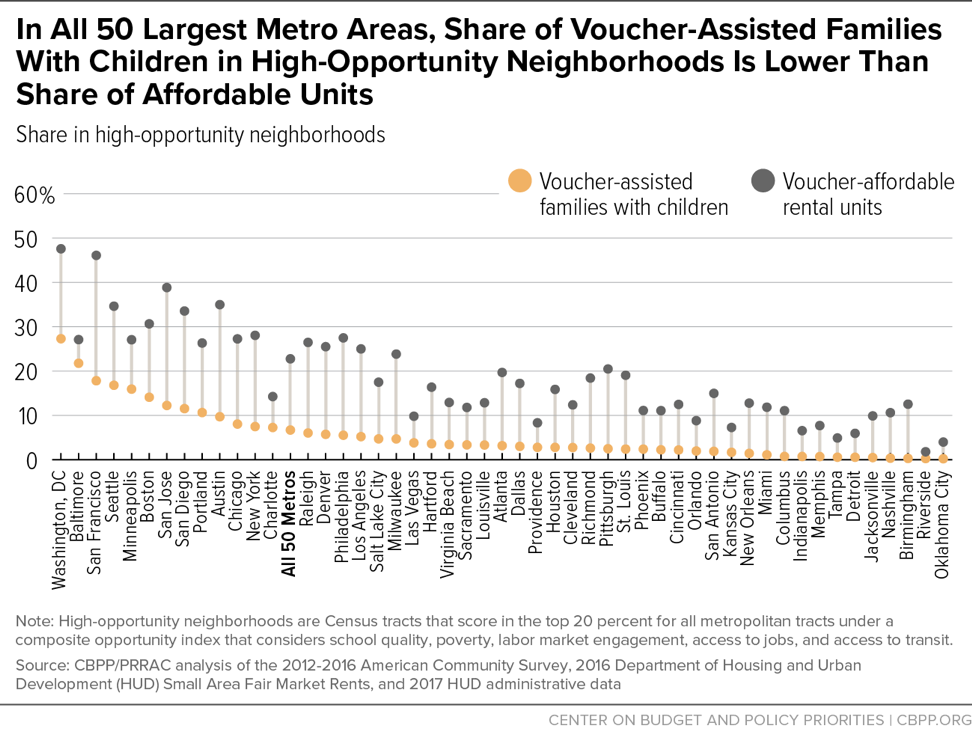

In every one of the 50 largest metro areas, the share of families using vouchers in high-opportunity neighborhoods is smaller than the share of voucher-affordable units in such neighborhoods. (See figure.) In contrast, the share living in low-opportunity areas far exceeds the share of voucher-affordable units in these areas.[12]

Voucher families face numerous barriers. They may not have adequate information on available housing options in their county or metro area or be aware of the difference in educational and other opportunities that a move to an unfamiliar area may provide. Landlords in areas where vouchers are uncommon may be unfamiliar with the HCV program or perceive the program as burdensome or less profitable than renting to other tenants.[13] Few public housing agencies (PHAs) actively recruit and retain new landlords, and many of their landlord listings do not include options in higher-opportunity neighborhoods as HUD requires.[14] While refusal to rent to families based on their race or ethnicity or because they have children is illegal, such practices persist.[15] About half of vouchers are administered in areas that do not prohibit landlords from discriminating against voucher holders.[16]

Even when a landlord in a high-opportunity neighborhood does consider renting to a voucher holder, PHAs’ voucher payment standards may not be high enough to cover the rent.[17] Additionally, landlords may have policies, such as requiring high security deposits or minimum credit scores, that families can’t meet.

Some high-opportunity neighborhoods have few units for rent due to exclusionary zoning policies that inhibit the building of multi-family properties. Vouchers can be — and frequently are — used to rent single-family homes, yet restrictions on the supply of multi-family housing can make it more difficult for voucher holders to move to such neighborhoods.

Comprehensive mobility programs are effective in helping families overcome these barriers, and, with additional funding and incentives, such programs could be implemented in more cities or expanded where they’re already available to reach more families.

The types of support that housing mobility programs provide varies; some examples of the types of services and additional financial assistance that either PHA staff or partnering local non-profit agencies may offer include:

- Informing families of high-opportunity areas’ advantages and helping them identify such areas using available evidence.

- Addressing financial barriers families may have, such as by providing financial coaching to improve credit scores or help saving to pay for moving costs. Some programs provide grants or loans to families to pay security deposits and application fees.

- Recruiting landlords in higher-opportunity areas, in some cases using modest financial incentives.

- Helping families search for affordable units that meet their individual needs.

- Providing post-move services, such as regular check-ins, resource coordination, and landlord/tenant mediation, to help families keep living in areas of opportunity.

Housing agencies may also adopt administrative policies and procedures to support voucher mobility programs including:

- Performing timely inspections and contract execution, and generally operating a well-run voucher program.

- Providing adequate time for a family to conduct a housing search.

- Offering strong customer service for both landlords and program participants.

- Ensuring voucher subsidies’ maximum limits are high enough to rent in higher-opportunity neighborhoods.

- Working collaboratively with PHAs in the region and streamlining the portability process to move across jurisdictions.

In some high-opportunity areas where few modestly priced rental units are available, some housing agencies have sought to increase the supply of potential homes by acquiring rental properties and setting aside a share of units for voucher holders.[18] Similarly, some housing agencies contract with developers of new rental housing in high-opportunity areas to “project-base” vouchers (that is, designate a specific number of them for use in a particular development), ensuring that the designated units will be available to low-income families.

Inspired by the 2015 research by Chetty and his colleagues, policymakers in 2019 launched a federal HCV Mobility Demonstration.[19] This demonstration will create opportunities for more agencies to implement housing mobility programs and for researchers to test which interventions are most cost effective and beneficial to families in overcoming barriers preventing moves to higher-opportunity neighborhoods. It also will provide about 1,000 additional housing vouchers for families to participate in the demonstration. While this demonstration represents an important first step, housing mobility programs would need to be more comprehensive and better funded to expand services to more families that want them.