The appropriations bills for fiscal year 2022 approved by the House Appropriations Committee[1] would make crucial investments in our country’s future after more than a decade of constrained funding levels for regular non-defense appropriations.[2] Many of these investments are particularly important to communities of color — especially Black, Latino, and Indigenous communities, which have been under-resourced for decades due to federal, state, and local policies.[3] At the same time, these investments would have broad-based impacts, providing protections and opportunities for many people and communities, including people of color, people with disabilities, and people with low incomes living in rural and urban communities alike.

This paper briefly highlights three areas where funding increases in the House bills would take important steps to support antiracist policies:[4]

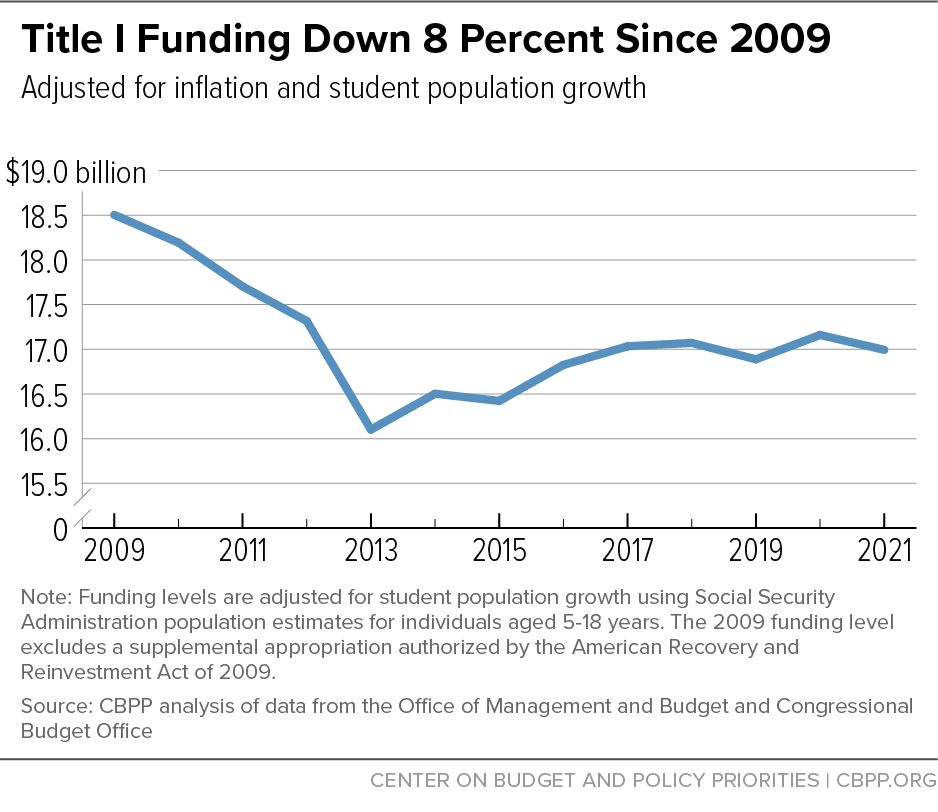

- K-12 funding for students from low-income backgrounds. Lack of access to quality education has long been a major barrier to opportunity for communities of color, and an important cause is the large gap in education funding between students of color and white students. Federal Title I (“Education for the Disadvantaged”) grants to schools serving low-income communities shrink this gap modestly, but funding for Title I fell by 8 percent between its 2009 peak and 2021, after adjusting for inflation and student population growth. The House bills would more than double Title I funding for 2022.

- Enforcement of federal civil rights laws. Enforcing civil rights laws and ensuring equal treatment for marginalized groups is one of the federal government’s most important responsibilities. The House bills would provide much-needed increases to federal civil rights offices such as the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission and the Office of Fair Housing and Equal Opportunity; these two entities, which were cut by roughly 15 percent between 2010 and 2021 after adjusting for inflation and population growth, would each receive a roughly 10 percent boost in 2022.

- Legal services for people with low incomes. The Legal Services Corporation (LSC) supports nonprofit legal aid agencies across the country that help people with low incomes in a wide range of civil legal matters. Access to legal aid is particularly important for low-income people of color, who face unlawful discrimination in crucial areas such as housing, employment, and health, and who, because of a long history and ongoing discrimination, are disproportionately low-income and unable to afford private legal counsel. Despite the large need for civil legal assistance, LSC funding has been cut by 15 percent over the past decade and by two-thirds since 1980, after adjusting for inflation and population growth. The House bills would boost LSC funding by 29 percent in 2022.

These are just three examples of non-defense discretionary (NDD) programs that can reduce racial disparities. The House bills, as well as those from the Senate Appropriations Committee,[5] include needed investments in many other areas that have major implications for racial equity, such as housing vouchers,[6] Minority Serving Institutions of higher education, and the Indian Health Service.

The House appropriations bills, following the lead of the Biden Administration budget, reflect a significant increase in overall funding for NDD: $109 billion (16 percent) above the 2021 level.[7] This increase is a key reason why they are able to take important steps to bolster racial equity. But in addition to boosting funding, policymakers often need to take further actions to promote equity and reduce harm. (See box.)

Congress has a responsibility to ensure that racial equity is advanced in the programs that it funds. For example, the House Appropriations Committee acknowledged this responsibility with regard to policing:

The Committee takes very seriously its solemn obligation to help improve the state of policing and ensure racial justice in the United States. The appalling mistreatment of African Americans and other minorities at the hands of police officers in communities throughout the country is a longstanding epidemic that demands immediate reforms throughout the Nation, including decisive action from this Committee.a

Increasing program funding alone will not automatically advance racial justice in some cases. Further legislative action may be needed, including establishing requirements that reduce harm. For example, the House Commerce-Justice-Science appropriations bill for 2022 would make state or local government receipt of Byrne Justice Assistance Grant (JAG) or Community Oriented Policing Services (COPS) funds conditional on their law enforcement agencies “maintain[ing] adequate policies and procedures designed to eliminate racial profiling in law enforcement, and . . . eliminat[ing] any existing practices that permit or encourage racial profiling in law enforcement,” among other requirements.

By conditioning funding on the elimination of discriminatory practices and policies, Congress can use federal funding as an incentive to end racist practices and promote racial justice. The executive branch then must fully implement these requirements to advance equity.

The House appropriations bill for the departments of Labor, Health and Human Services, and Education would more than double funding for Title I grants to schools serving a large number or proportion of students from families with low incomes, from $16.5 billion in 2021 to $36.0 billion in 2022. Title I supports the development of school programs that allow all students to meet state academic standards; eligible schools use these grants to fund a wide range of activities and programs, including after-school programs and professional development for teachers. The House increase would enable Title I to narrow the large gaps in education funding between white students and students who are Black, Hispanic, or in a family with low income.[8] The committee report also instructs the Department of Education to reform Title I regulations to better target funding to the students who need it most.

Over half a century after the modern civil rights movement began, the U.S. education system still systematically disadvantages students of color. This is in part because families of color disproportionately live in low-income neighborhoods and have lower incomes (due to parents’ inequitable access to quality education, among other things). As a result, Black, Latino, and Indigenous students are more likely to attend a high-poverty, under-resourced school than their white peers.[9] Schools with higher concentrations of children experiencing poverty are often inadequately funded compared to other schools, due in part to many districts’ heavy reliance on property taxes for funding.[10]

Barriers to high-quality education at under-resourced schools perpetuate a cycle of racial inequity and prevent many students of color from thriving and fully contributing to society. For example, extensive research finds a link between educational attainment and health outcomes such as life expectancy.[11] A similar link exists between education and income, which in turn affects health outcomes. Barriers to high-quality education also perpetuate the cycle of generational poverty that many children experience.

Since 1965, Title I grants have responded to these funding disparities by supporting services for school-age children living in difficult financial or family circumstances.[12] For example, these grants can fund after-school programs for eligible students or professional development for school personnel who work directly with these students, as noted above. For schools with higher concentrations of students from families with low incomes, grants can also support programs that address the needs of the entire school, such as counseling services or programs to prepare students for entering higher education or the workforce. Federal rules require that all Title I funds be used to supplement, not supplant, other funding sources.

Title I grants have been instrumental in increasing racial equity in K-12 education; the program narrows K-12 racial spending gaps by approximately $100 to $200 per pupil nationwide, the Brookings Institution estimates. But inadequate appropriations have limited the program’s reach. Even after taking Title I into account, Latino students receive nearly $1,200 less education spending per pupil than white students, while Black students receive almost $400 less than white students. Children from families with low incomes face a similar gap of about $400 per pupil compared to their higher-income peers. [13]

The House bill’s historic Title I increase would come after more than a decade of cuts and insufficient increases to the program. After adjusting for inflation and student population growth, Title I funding fell by 8 percent between its 2009 peak and 2021.[14] (See Figure 1.) The House bill would sharply break from this pattern by raising program funding 95 percent above the 2009 level, after adjusting for inflation and student population. This would mark an important step toward reversing many decades of chronic underinvestment in education for children of color and children with low incomes.

The House bills would increase funding for federal civil rights offices such as the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC), which enforces federal laws barring discrimination against job applicants or employees, and the Office of Fair Housing and Equal Opportunity, which enforces federal fair housing policies and laws.[15] With the increases, these agencies could start rebuilding their staffs after a decade of cuts and better enforce non-discrimination laws. Funding for both the EEOC and Office of Fair Housing and Equal Opportunity declined by 15 percent between 2010 and 2021 after adjusting for inflation and population growth. In the House bills, the EEOC would receive a 10 percent boost in 2022 and the Office of Fair Housing and Equal Opportunity an 11 percent increase (measured in current dollars).

The civil rights offices in agencies throughout the executive branch play a crucial role in combating discrimination on the basis of race, religion, sexual orientation, gender identity, national origin, and disability. When empowered and well-funded, they can do much to protect people of color, people with disabilities, women, and other groups that have faced discrimination. For example, the first Office for Civil Rights[16] was in the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare (predecessor to the current departments of Education and Health and Human Services) and was founded in 1967 in part to desegregate schools. It helped lower the share of Black students attending all-Black schools from 98 percent to less than 9 percent over eight years.[17]

While legal segregation in schools has been prohibited for decades, the Education Department’s Office for Civil Rights has much unfinished business in helping protect Black students and other students of color from discrimination in educational offerings and disciplinary policies, as well as helping protect them from racial violence in schools. It also plays a critical role in enforcing the statutory requirements guaranteeing equal access to free public education for students with disabilities.

Lack of funding undermines the offices’ capacity to respond to discrimination complaints, proactively identify areas of non-compliance, provide clear guidance, and collect and share data on the state of racial equity across the country. For example, the Education Department’s Office for Civil Rights received five times more complaints in 2016 than in 1980, but its staff was halved over that period.[18]

Funding for most federal civil rights offices has been cut significantly over the past decade. The House appropriations bills would reverse that trend by boosting funding for many federal civil rights offices, in some cases significantly. (See Table 1.) When paired with effective implementation, even small funding increases in these offices can have an outsized impact on historically marginalized communities. By investing in them, the House appropriations bills would take an important step toward addressing the persistent effects of systemic racism and discrimination throughout our nation’s history.

| TABLE 1 |

| In millions |

| Office |

FY 2021 (enacted) |

FY 2022

(House bills) |

| Equal Employment Opportunity Commission |

$404.5 |

$445.9 |

| Justice Dept.: Civil Rights Division |

$158.1 |

$193.2 |

| Education Dept.: Office for Civil Rights |

$131.0 |

$144.0 |

| Labor Dept.: Office of Federal Contract Compliance* |

$106.0 |

$140.7 |

| Housing and Urban Development Dept.: Office of Fair Housing and Equal Opportunity |

$79.8 |

$88.7 |

| Health and Human Services Dept.: Office for Civil Rights |

$38.8 |

$47.9 |

| Agriculture Dept.: Office of Civil Rights |

$23.7 |

$36.8 |

| Commission on Civil Rights |

$12.5 |

$13.0 |

The House appropriations bill for Commerce, Justice, and Science would raise funding for the Legal Services Corporation by 29 percent in 2022, the largest one-year percentage increase (measured in current dollars) over the past four decades.

LSC distributes funds to more than 130 independent, nonprofit legal aid agencies, which assist people with incomes below 125 percent of the federal poverty line in civil legal matters such as housing, family issues (e.g., adoption, child custody, domestic abuse, and divorce), access to health care, income support and other benefits, employment law, and consumer finance and debt collection.

Accessing legal aid is particularly important for people of color with low incomes, who face unlawful racial discrimination in crucial areas such as housing and employment. Yet financial and language barriers prevent many individuals from getting the legal assistance they need. LSC has helped expand access to legal aid for many people of color with low incomes. Among the clients of LSC grantees in 2020, 28 percent were Black, 18 percent were Hispanic, 3 percent were AAPI, and 2 percent were Native American.[19]

For one example of how LSC pushes back against systematic racism, consider debt collection cases. Due to generations of limited economic opportunity and security, families of color are more likely to incur significant debt and less likely to have significant wealth — and thus are far more likely to face a debt collection case.[20] Nationwide, nearly 13 percent of Latino families and 8 percent of Black families have debt payments exceeding 40 percent of their income, compared to fewer than 7 percent of white families. And when a debt collector sues a family, the debt collector is seven times more likely than the family to be represented by a lawyer.[21] Defendants are far more likely to win debt collection cases if they have legal representation, LSC has found, which is why lack of available counsel can have serious — and racially disparate — consequences.

Despite its important role, LSC has been cut severely over the last few decades. Between 1980 and 2021, appropriations for LSC were halved when adjusted for inflation and cut by two-thirds when adjusted for inflation and population growth. Looking just at the most recent decade, LSC funding fell by 15 percent between 2010 and 2021, after adjusting for inflation and population growth. These funding cuts have directly affected LSC’s ability to achieve its mission; from 2010 to 2013, when LSC’s basic field funding dropped by 20 percent, the number of cases closed dropped by 18.5 percent.[22] A 2017 LSC survey found that, largely due to insufficient resources, its grantees could provide adequate legal services for fewer than half of the problems brought to them and provided no help at all in over 40 percent of cases.[23]

The COVID-19 pandemic and recession have greatly increased the number of people eligible for legal aid through LSC.[24] And the need for civil legal services concerning matters such as evictions, unemployment insurance, domestic violence, and health issues has risen significantly.[25] Many of these issues disproportionately affect people of color, especially Black and Latino people. For example, the Black and Latino unemployment rates are consistently higher than the white unemployment rate, with disparities widening in times of economic hardship such as the pandemic.

To address this important need, the House bill would boost LSC funding from $465 million in 2021 to $600 million in 2022, which would help LSC work toward its goal of addressing 60 percent more eligible civil legal cases than it served in 2019.[26] To meet these targets, Congress should continue to invest in LSC in future years, as well as enacting the crucial increase in the House bill for 2022.