Revised June 25th, 2017[1]

The House-passed health care bill (the American Health Care Act) slashed subsidies that help people afford individual market coverage, increasing out-of-pocket costs by thousands of dollars for people who get their coverage through the Affordable Care Act (ACA) marketplaces.

While the Senate bill’s cuts to tax credits are structured differently and are somewhat smaller on average, their broad consequences would essentially be the same: coverage and care would become much less affordable for millions of people with modest incomes. Moreover, the Senate’s subsidy changes, like those in the House bill, would particularly harm older people, lower-income people, and people in high-cost states.

The Senate health bill, released June 22, makes five major changes affecting marketplace premiums and financial assistance.

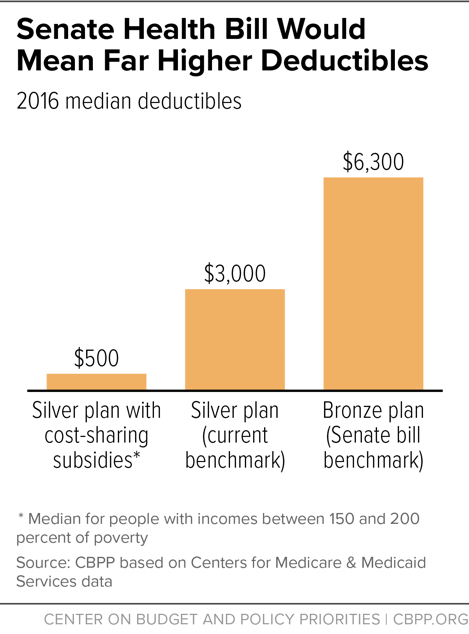

First, it makes an across-the-board cut to premium tax credits by linking them to less generous health coverage. Today, premium tax credits are based on the value of “silver plan” coverage: coverage with a 70 percent actuarial value. In other words, tax credits are calibrated so consumers can afford plans that cover 70 percent of their medical costs (on average); consumers pay the remaining 30 percent through deductibles, copays, and coinsurance. Under the Senate bill, tax credits would instead be based on the cost of a plan with an actuarial value of 58 percent — roughly equivalent to current “bronze plan” coverage. This means consumers would have to pay 42 percent of the cost of health services that their insurance plan covers, rather than 30 percent. This would mean much higher deductibles: in 2016, the median deductible for bronze plans was about twice as high as the median deductible for silver plans — $6,300 versus $3,000.[2]

Second, the bill rearranges the current tax-credit schedule, generally reducing premium tax credits for older people while increasing them for younger people. For example, under current law in 2020, people with incomes between 300 and 350 percent of the poverty level (between $36,000 and $42,000 for a single person) would pay about 9.9 percent of their income in premiums to obtain “silver plan” coverage — with the tax credits covering the remainder.[3] Under the Senate bill, older people in this income range would pay about 12 to 17 percent of income for the lower-value “bronze” coverage, meaning that they would pay significantly more in premiums to buy plans that have much higher deductibles. (Younger people would pay 4.5 to 6.7 percent of income for bronze-plan coverage.)[4]

In dollar terms, a 60-year-old with income of $36,000 would see her out-of-pocket premium rise from $3,425 for silver-plan coverage to $4,174 for (skimpier) bronze-plan coverage due to this change. In contrast, a 25-year-old would see her premium fall from $3,425 to $1,620.

Third, the Senate bill eliminates tax credits entirely for people with incomes between 350 percent and 400 percent of the poverty line — about $42,000 to $48,000 for a single person.

Fourth, like the House bill, the Senate bill would allow insurers to charge older people up to five times as much as younger people in premiums (before the tax-credit premium subsidies are applied), compared to a three-to-one limit today.

Finally, also like the House bill, the Senate bill eliminates cost-sharing reductions (CSRs), or subsidies that reduce deductibles, copayments, and coinsurance for lower-income consumers — those with incomes below 250 percent of the poverty line (about $30,000 for a single person).

These changes would make coverage and care significantly less affordable than they are today. And while the Senate bill, unlike the House bill, maintains the ACA’s approach of basing tax credits on income and geography, as well as age, it would still impose the largest cost increases on lower-income people, older people, and people in high-cost states.

Reductions in Tax Credits and Increases in Premiums

Appendix Table 1 shows the combined effects of the Senate bill’s changes in premiums — after accounting for tax-credit subsidies — for consumers in different states at three different income levels (150 percent, 300, and 350 percent of the poverty line) and three different ages (30, 45, and 60). The tables estimate consumers’ change in premiums under the Senate bill, assuming that they wanted to continue purchasing current benchmark coverage (i.e., silver plans) and that they faced the average benchmark premium for such coverage in their state. (For a detailed explanation of the methodology behind these calculations, see the Appendix.)

As the tables show, the Senate bill’s changes would increase premiums, net of tax credits, for most marketplace consumers who receive subsidies (which is the great bulk of those consumers), although younger people at some income levels in some states would see premium decreases. The premium increases would be especially large for:

- Older people with modest incomes, who would be affected both by the bill’s across-the-board cut to the value of the premium tax credits as a result of tying the tax credits to less comprehensive health coverage, and by the changes to the tax credit schedule noted above that increase the percentage of income that many people would have to pay out of pocket in premiums. For a 60-year-old with income of 35 0 percent of the poverty level (about $42 ,000 today) facing the average premium on HealthCare.gov, out-of-pocket premiums would jump by an estimated $4,994. Premiums would rise by $ 2,022 for a 45-year-old at this income level, and fall by $75 for a 30-year-old. Premiums would rise by $2,694 for a 60-year old with income of 300 percent of the poverty line, and by $1,903 for a 60-year old with income of 150 percent of the poverty line.

-

People in high-cost states, who would face especially large premium increases primarily because the across-the-board cuts to the premium tax credits would be larger in these states than in other states. In states where health costs — and hence premiums — are high, the difference in premiums between more and less generous coverage also is high. Under the Senate bill, as explained above, the plans to which the tax-credit subsidies would be tied would cover only 58 percent of consumers’ health care costs, rather than 70 percent as under current law. As a result, to maintain their current coverage (i.e., to maintain a plan that covers 70 percent of their health costs), consumers would have to pay more. And the amount by which their premiums would rise would be greater in states that have high health-care costs, because premiums would go up by an amount sufficient to cover 12 percent of average health care costs (the difference between the health plan covering 70 percent of medical costs and 58 percent of these costs). That 12 percent is a larger amount in states where health care costs are higher.

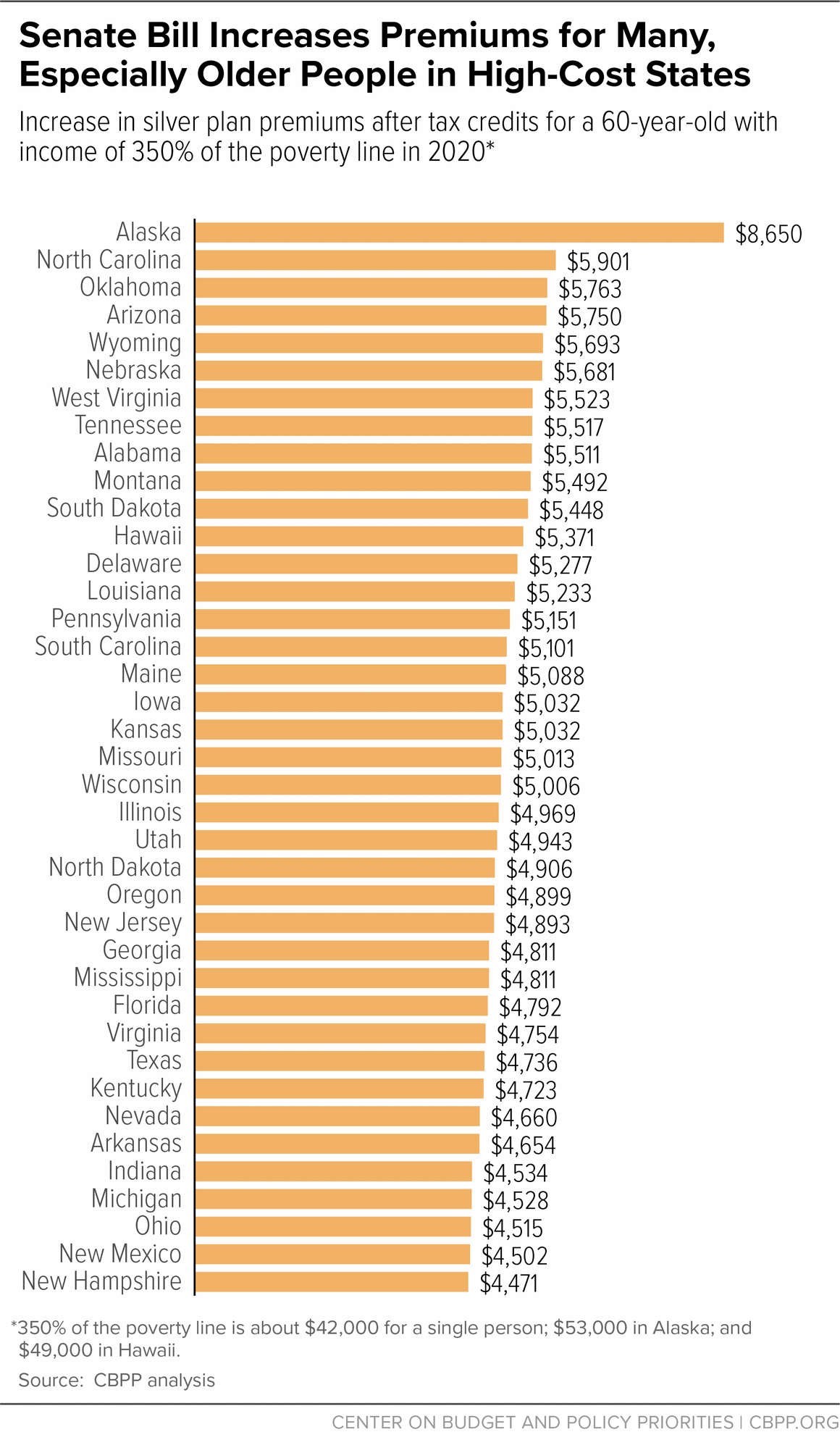

As Figure 1 shows, out-of-pocket premium increase for a 60-year old with income of 350 percent of the poverty level would range from about $4,000 in New Hampshire to over $8,000 in Alaska.

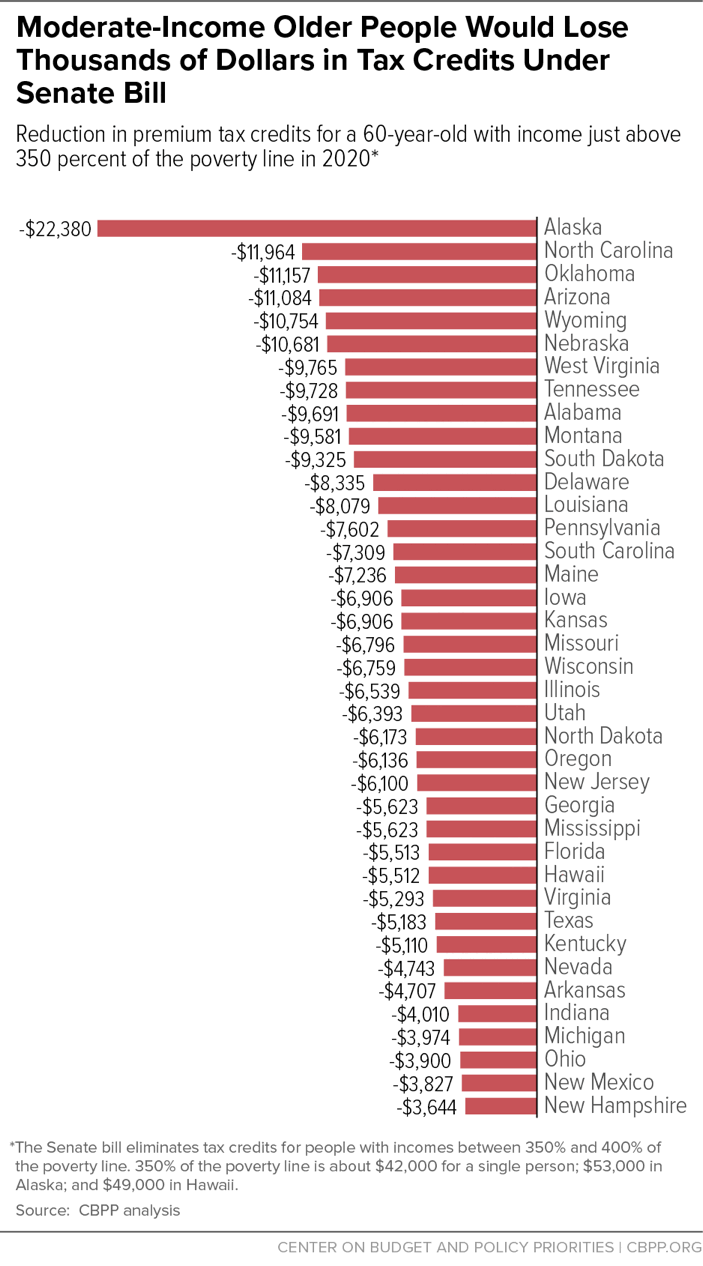

For moderate-income people who would lose tax credits altogether under the Senate bill — those with incomes between 350 and 400 percent of the poverty level — premium increases would generally be even larger. As with the bill’s other changes, older people and people in high-cost states would see the largest cost increases, because they receive the largest tax credits under current law as a result of their states having the highest health care costs. A 60-year-old just above 350 percent of the poverty line in Alaska would lose tax credits worth more than $22,000. But as Figure 2 shows, older people in all states at these income levels would lose thousands of dollars in tax credits.

Notably, a number of Senate Republicans have criticized the ACA for cutting off financial assistance abruptly at 400 percent of the poverty line.[5] But the Senate bill, by lowering that cut-off to 350 percent of the poverty line, would likely increase the number of people affected by the so-called “cliff” in assistance, and could make the cliff steeper.

Consumers could try to keep premiums down by switching from their current plan to the new, lower-value benchmark plan (i.e., to a “bronze” plan that covers 58 percent of medical costs). If so, however, they would see very significant increases in their deductibles, and many older people with modest incomes would still see premium increases as well. In addition, marketplace consumers with incomes below 250 percent of the poverty line would see large increases in their deductibles even if they maintained silver-plan coverage — because the bill eliminates cost-sharing-reduction subsidies. (See Figure 3.)

-

For consumers switching from silver to bronze plan coverage, deductibles would roughly double. As noted above, the median deductible for bronze plans is currently $6,300, compared to $3,000 for silver plans.

Moreover, although middle-aged people could generally keep their premiums roughly constant by switching to bronze plans, and younger people could reduce their premiums modestly by doing so, modest-income older people would see significant increases in premiums even if they switched to bronze plans with much higher deductibles, because of the provision in the Senate bill raising the percentage of income that older people must pay in premiums before tax-credit subsidies kick in.

-

And for people with incomes below 200 percent of the poverty level — who today are eligible for significant cost sharing assistance — deductibles would rise sharply even if they paid higher premiums to stay in a silver plan. Currently, the deductibles that these people face are well below $1,000 because of the cost-sharing subsidies. The Senate bill ends these subsidies after 2019, however, causing the deductibles these people would face to spike by thousands of dollars.

Like the House bill, the Senate bill effectively ends the ACA’s expansion of Medicaid, which has enabled 31 states and the District of Columbia to extend coverage to millions of adults with incomes below 138 percent of the poverty line. Some congressional Republicans have argued that the millions of poor and near-poor adults losing Medicaid would be able to buy health insurance in the private individual market instead.[6]

In practice, however, the overwhelming majority of those losing Medicaid coverage would end up either uninsured or underinsured.

- Premiums alone would put coverage out of reach for many of those losing Medicaid coverage. Under the Senate bill, people losing Medicaid would have to pay premiums equaling 2 percent of their income to purchase individual market coverage. While this is much lower than the premiums they would pay under the House bill,[7] a large body of research finds that premiums at these or even lower levels put coverage out of reach for many people in poverty.[8]

- More importantly, as discussed above, the benchmark plans that people could purchase for 2 percent of their income would have deductibles in the range of $6,300. For a person at the poverty line, a $6,300 deductible equals about half of her annual income. Even if they could afford their premiums, low-income people enrolled in benchmark coverage could not afford the out-of-pocket payments required to obtain health care. And, knowing that, they would be even less likely to sign up for coverage and cut back on other expenses like rent, transportation, or food in order to stay current on their premiums.

- In addition, the Senate bill, like the House bill, would allow states to waive the ACA’s requirements that plans cover essential health benefits. The Congressional Budget Office estimated that this could result in individual market plans in up to half the country dropping coverage for services including mental health and substance use treatment.[9] These services are particularly important to low-income people enrolled in Medicaid expansion coverage.[10]

The Medicaid expansion has allowed millions of low-income adults to gain not just coverage but access to health care. One recent study found that expansion led to increases in the share of people getting check-ups, getting regular care for chronic conditions, and reporting that they are in excellent health, as well as reductions in the share of people skipping medications due to cost, relying on the emergency room for care, and screening positive for depression.[11] The Senate bill would reverse most or all of these gains. It would also prevent states that have not yet expanded Medicaid from ever sharing in these gains, since it would prevent these states from receiving the enhanced federal match for expansion, even for the limited period in which it would remain available under the Senate bill.

Senator Shelly Moore Capito of West Virginia recently said that if the Medicaid expansion were to end, she would want to see the expansion population transition to “coverage that’s as good as the Medicaid coverage that folks are on.”[12] The coverage poor and near-poor people could access in the individual market under the Senate bill comes nowhere close to meeting that test.

Our projections for premiums and tax credits under the ACA and the Senate bill draw on data on actual premiums and tax credits from the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) and on projections from the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) and the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) Office of the Actuary.

Premiums. We obtain data on 2017 benchmark marketplace premiums by state from HHS.[13] To project premiums for 2020, we inflate 2017 premiums to 2020 using National Health Expenditure (NHE) projections from the CMS Office of the Actuary. [14] To project premiums under the House bill for different age groups, we follow the approach described in a recent Brookings analysis to convert CBO’s estimated changes in premiums for silver plan coverage under the House bill for people age 21, 40, and 64 into a complete forecast of premium changes by age.[15] While the Senate bill differs from the House bill in a number of respects, the major provisions affecting premiums — changes in age rating, elimination of the individual mandate, and reinsurance funding — are the same or very similar.

Tax credits. To calculate tax credits for hypothetical consumers, we follow the approach used in a recent Kaiser Family Foundation analysis.[16] Specifically, we inflate the ACA’s required premium contributions using the ratio of growth in employer-sponsored insurance spending per enrollee and gross domestic product per capita from the NHE and inflate federal poverty guidelines using consumer price index projections from CBO. We then compute tax credits under both the ACA rules and the alternative rules specified in the Senate bill.

As discussed in the main text, the Senate bill alters the benchmark plan used to calculate tax credits. To estimate the effects of this change on tax credits, we assume that benchmark premiums fall by about 13 percent: the expected difference in premiums between a plan that covers 66 percent of costs (the minimum allowed actuarial value for a silver plan) and a plan that covers 58 percent of costs.[17]

| TABLE 1 |

|---|

| |

30-Year-Old |

45-Year-Old |

60-Year-Old |

|---|

| |

Senate Bill |

Change From Current Law |

Senate Bill |

Change From Current Law |

Senate Bill |

Change From Current Law |

|---|

| Alabama |

1,485 |

694 |

1,823 |

1,032 |

3,211 |

2,420 |

| Alaska |

2,361 |

1,374 |

3,030 |

2,042 |

5,777 |

4,789 |

| Arizona |

1,554 |

763 |

1,925 |

1,134 |

3,450 |

2,659 |

| Arkansas |

1,239 |

448 |

1,457 |

666 |

2,354 |

1,563 |

| Delaware |

1,418 |

627 |

1,723 |

932 |

2,977 |

2,187 |

| Florida |

1,279 |

488 |

1,516 |

725 |

2,492 |

1,701 |

| Georgia |

1,284 |

493 |

1,524 |

734 |

2,511 |

1,720 |

| Hawaii |

1,431 |

521 |

1,684 |

774 |

2,725 |

1,815 |

| Illinois |

1,329 |

539 |

1,592 |

801 |

2,669 |

1,878 |

| Indiana |

1,205 |

414 |

1,406 |

615 |

2,234 |

1,443 |

| Iowa |

1,347 |

557 |

1,618 |

828 |

2,732 |

1,941 |

| Kansas |

1,347 |

557 |

1,618 |

828 |

2,732 |

1,941 |

| Kentucky |

1,259 |

468 |

1,487 |

696 |

2,423 |

1,632 |

| Louisiana |

1,405 |

614 |

1,704 |

914 |

2,933 |

2,143 |

| Maine |

1,364 |

573 |

1,643 |

852 |

2,788 |

1,998 |

| Michigan |

1,203 |

412 |

1,403 |

613 |

2,228 |

1,437 |

| Mississippi |

1,284 |

493 |

1,524 |

734 |

2,511 |

1,720 |

| Missouri |

1,342 |

551 |

1,610 |

819 |

2,713 |

1,922 |

| Montana |

1,479 |

689 |

1,815 |

1,024 |

3,192 |

2,401 |

| Nebraska |

1,534 |

743 |

1,895 |

1,104 |

3,381 |

2,590 |

| Nevada |

1,241 |

450 |

1,460 |

669 |

2,360 |

1,569 |

| New Hampshire |

1,187 |

396 |

1,379 |

588 |

2,171 |

1,380 |

| New Jersey |

1,308 |

517 |

1,559 |

768 |

2,593 |

1,802 |

| New Mexico |

1,196 |

405 |

1,393 |

602 |

2,202 |

1,412 |

| North Carolina |

1,597 |

806 |

1,989 |

1,198 |

3,601 |

2,810 |

| North Dakota |

1,311 |

521 |

1,565 |

774 |

2,606 |

1,815 |

| Ohio |

1,199 |

408 |

1,398 |

607 |

2,215 |

1,424 |

| Oklahoma |

1,557 |

766 |

1,930 |

1,139 |

3,463 |

2,672 |

| Oregon |

1,310 |

519 |

1,562 |

771 |

2,599 |

1,809 |

| Pennsylvania |

1,382 |

591 |

1,669 |

879 |

2,851 |

2,061 |

| South Carolina |

1,367 |

577 |

1,648 |

857 |

2,801 |

2,010 |

| South Dakota |

1,467 |

676 |

1,796 |

1,005 |

3,148 |

2,357 |

| Tennessee |

1,487 |

696 |

1,825 |

1,034 |

3,217 |

2,426 |

| Texas |

1,263 |

472 |

1,492 |

701 |

2,436 |

1,645 |

| Utah |

1,322 |

531 |

1,581 |

790 |

2,643 |

1,853 |

| Virginia |

1,268 |

477 |

1,500 |

709 |

2,454 |

1,664 |

| West Virginia |

1,488 |

698 |

1,828 |

1,037 |

3,223 |

2,432 |

| Wisconsin |

1,340 |

549 |

1,608 |

817 |

2,706 |

1,916 |

| Wyoming |

1,537 |

746 |

1,900 |

1,110 |

3,393 |

2,603 |

| HealthCare.gov state average** |

1,337 |

546 |

1,602 |

811 |

2,694 |

1,903 |

| TABLE 2 |

|---|

| |

30-Year-Old |

45-Year-Old |

60-Year-Old |

|---|

| |

Senate Bill |

Change From Current Law |

Senate Bill |

Change From Current Law |

Senate Bill |

Change From Current Law |

|---|

| Alabama |

3,027 |

-729 |

4,333 |

577 |

6,967 |

3,211 |

| Alaska |

4,288 |

-405 |

6,166 |

1,474 |

10,469 |

5,777 |

| Arizona |

3,096 |

-661 |

4,436 |

679 |

7,207 |

3,450 |

| Arkansas |

2,781 |

-975 |

3,968 |

212 |

6,110 |

2,354 |

| Delaware |

2,960 |

-796 |

4,234 |

478 |

6,734 |

2,977 |

| Florida |

2,821 |

-936 |

4,027 |

271 |

6,249 |

2,492 |

| Georgia |

2,826 |

-930 |

4,035 |

279 |

6,268 |

2,511 |

| Hawaii |

3,205 |

-1,117 |

4,573 |

251 |

7,047 |

2,725 |

| Illinois |

2,872 |

-885 |

4,102 |

346 |

6,425 |

2,669 |

| Indiana |

2,747 |

-763 |

3,917 |

161 |

5,990 |

2,234 |

| Iowa |

2,890 |

-867 |

4,129 |

373 |

6,488 |

2,732 |

| Kansas |

2,890 |

-867 |

4,129 |

373 |

6,488 |

2,732 |

| Kentucky |

2,801 |

-955 |

3,998 |

241 |

6,179 |

2,423 |

| Louisiana |

2,947 |

-809 |

4,215 |

459 |

6,690 |

2,933 |

| Maine |

2,906 |

-851 |

4,153 |

397 |

6,545 |

2,788 |

| Michigan |

2,745 |

-750 |

3,914 |

158 |

5,984 |

2,228 |

| Mississippi |

2,826 |

-930 |

4,035 |

279 |

6,268 |

2,511 |

| Missouri |

2,884 |

-872 |

4,121 |

365 |

6,469 |

2,713 |

| Montana |

3,022 |

-735 |

4,325 |

569 |

6,948 |

3,192 |

| Nebraska |

3,076 |

-681 |

4,406 |

650 |

7,137 |

3,381 |

| Nevada |

2,783 |

-973 |

3,971 |

214 |

6,116 |

2,360 |

| New Hampshire |

2,729 |

-628 |

3,890 |

134 |

5,927 |

2,171 |

| New Jersey |

2,850 |

-907 |

4,070 |

314 |

6,350 |

2,593 |

| New Mexico |

2,738 |

-696 |

3,904 |

147 |

5,959 |

2,202 |

| North Carolina |

3,139 |

-617 |

4,500 |

744 |

7,358 |

3,601 |

| North Dakota |

2,853 |

-903 |

4,076 |

319 |

6,362 |

2,606 |

| Ohio |

2,741 |

-723 |

3,909 |

152 |

5,971 |

2,215 |

| Oklahoma |

3,099 |

-657 |

4,441 |

684 |

7,219 |

3,463 |

| Oregon |

2,852 |

-905 |

4,073 |

316 |

6,356 |

2,599 |

| Pennsylvania |

2,924 |

-832 |

4,180 |

424 |

6,608 |

2,851 |

| South Carolina |

2,909 |

-847 |

4,159 |

402 |

6,557 |

2,801 |

| South Dakota |

3,009 |

-748 |

4,307 |

550 |

6,904 |

3,148 |

| Tennessee |

3,029 |

-728 |

4,336 |

580 |

6,973 |

3,217 |

| Texas |

2,805 |

-952 |

4,003 |

247 |

6,192 |

2,436 |

| Utah |

2,864 |

-892 |

4,092 |

335 |

6,400 |

2,643 |

| Virginia |

2,810 |

-946 |

4,011 |

255 |

6,211 |

2,454 |

| West Virginia |

3,031 |

-726 |

4,339 |

582 |

6,980 |

3,223 |

| Wisconsin |

2,882 |

-874 |

4,119 |

362 |

6,463 |

2,706 |

| Wyoming |

3,079 |

-677 |

4,411 |

655 |

7,150 |

3,393 |

| HealthCare.gov state average** |

2,879 |

-878 |

4,113 |

357 |

6,450 |

2,694 |

| TABLE 3 |

|---|

| |

30-Year-Old |

45-Year-Old |

60-Year-Old |

|---|

| |

Senate Bill |

Change From Current Law |

Senate Bill |

Change From Current Law |

Senate Bill |

Change From Current Law |

|---|

| Alabama |

4,800 |

417 |

6,798 |

2,416 |

9,893 |

5,511 |

| Alaska |

6,502 |

1,028 |

9,245 |

3,771 |

14,125 |

8,650 |

| Arizona |

4,868 |

486 |

6,900 |

2,518 |

10,133 |

5,750 |

| Arkansas |

3,538 |

-263 |

5,259 |

877 |

9,036 |

4,654 |

| Delaware |

4,733 |

350 |

6,699 |

2,316 |

9,660 |

5,277 |

| Florida |

3,851 |

-287 |

5,726 |

1,343 |

9,175 |

4,792 |

| Georgia |

3,894 |

-290 |

5,789 |

1,407 |

9,194 |

4,811 |

| Hawaii |

4,108 |

-306 |

6,107 |

1,065 |

10,414 |

5,371 |

| Illinois |

4,251 |

-132 |

6,319 |

1,937 |

9,351 |

4,969 |

| Indiana |

3,267 |

-243 |

4,856 |

474 |

8,916 |

4,534 |

| Iowa |

4,394 |

11 |

6,532 |

2,149 |

9,414 |

5,032 |

| Kansas |

4,394 |

11 |

6,532 |

2,149 |

9,414 |

5,032 |

| Kentucky |

3,695 |

-275 |

5,492 |

1,110 |

9,105 |

4,723 |

| Louisiana |

4,720 |

338 |

6,680 |

2,297 |

9,616 |

5,233 |

| Maine |

4,522 |

139 |

6,618 |

2,236 |

9,471 |

5,088 |

| Michigan |

3,252 |

-242 |

4,835 |

453 |

8,910 |

4,528 |

| Mississippi |

3,894 |

-290 |

5,789 |

1,407 |

9,194 |

4,811 |

| Missouri |

4,351 |

-32 |

6,468 |

2,085 |

9,395 |

5,013 |

| Montana |

4,794 |

412 |

6,790 |

2,408 |

9,874 |

5,492 |

| Nebraska |

4,849 |

466 |

6,871 |

2,488 |

10,063 |

5,681 |

| Nevada |

3,552 |

-265 |

5,280 |

898 |

9,042 |

4,660 |

| New Hampshire |

3,124 |

-233 |

4,644 |

374 |

8,853 |

4,471 |

| New Jersey |

4,080 |

-303 |

6,065 |

1,682 |

9,276 |

4,893 |

| New Mexico |

3,195 |

-238 |

4,750 |

382 |

8,885 |

4,502 |

| North Carolina |

4,912 |

529 |

6,965 |

2,582 |

10,284 |

5,901 |

| North Dakota |

4,108 |

-274 |

6,107 |

1,725 |

9,288 |

4,906 |

| Ohio |

3,224 |

-240 |

4,793 |

410 |

8,897 |

4,515 |

| Oklahoma |

4,872 |

490 |

6,906 |

2,523 |

10,145 |

5,763 |

| Oregon |

4,094 |

-289 |

6,086 |

1,704 |

9,282 |

4,899 |

| Pennsylvania |

4,665 |

282 |

6,645 |

2,263 |

9,534 |

5,151 |

| South Carolina |

4,550 |

168 |

6,624 |

2,241 |

9,484 |

5,101 |

| South Dakota |

4,782 |

399 |

6,771 |

2,389 |

9,830 |

5,448 |

| Tennessee |

4,802 |

419 |

6,801 |

2,418 |

9,899 |

5,517 |

| Texas |

3,723 |

-277 |

5,535 |

1,152 |

9,118 |

4,736 |

| Utah |

4,194 |

-189 |

6,235 |

1,852 |

9,326 |

4,943 |

| Virginia |

3,766 |

-280 |

5,598 |

1,216 |

9,137 |

4,754 |

| West Virginia |

4,803 |

421 |

6,804 |

2,421 |

9,906 |

5,523 |

| Wisconsin |

4,336 |

-46 |

6,447 |

2,064 |

9,389 |

5,006 |

| Wyoming |

4,852 |

470 |

6,876 |

2,494 |

10,076 |

5,693 |

| HealthCare.gov state average** |

4,308 |

-75 |

6,404 |

2,022 |

9,376 |

4,994 |