A number of states are implementing or considering policies that would take Medicaid coverage away from enrollees not working a specified number of hours each month. Such work requirements are unlikely to promote employment and may be counterproductive: research in other programs has shown that conditioning basic assistance on work is unlikely to increase long-term employment rates or incomes,[1] and taking away health coverage and access to care is likely to be harmful and may impede employment for some.[2] Montana, in contrast, has created a workforce promotion program for Medicaid enrollees that targets state resources toward reducing barriers to work, rather than toward creating new bureaucracy to track employment and exemption paperwork for all enrollees. Programs like Montana’s can help the minority of Medicaid enrollees who can work but are not working find and hold jobs, without the harmful and often counterproductive effects of work requirements.

Montana’s Health and Economic Livelihood Partnership Link (HELP-Link) program targets outreach and services to the minority of Medicaid enrollees who do not have disabilities or similarly severe barriers to work but who are not working, often due to challenges such as limited skills and lack of access to transportation, child care, and other needed work supports. Montana’s approach targets Medicaid enrollees who are looking for work or better jobs, linking them with services such as career counseling, on-the-job training programs, and subsidized employment. In its first two years, the program has shown promise and has generated strong participation among enrollees, likely because the state has engaged in intensive outreach, offered meaningful services, and provided trainings to service providers and partners in how to meet the needs of low-income Medicaid enrollees. Montana Governor Steve Bullock recently highlighted the success of the program, stating, “This model and the evidence of its success comes at such an extremely important time in our nation. While other states are pushing work requirements that have it backwards, we are putting more people to work with higher wages.”[3]

Unlike Montana’s experience, Indiana and Arkansas have expressed disappointment with their work referral programs and cited low participation as part of their justification for imposing work requirements in their Medicaid programs. However, it’s likely these states did not invest in the outreach and personalized services Montana offers. Moreover, these states may have unrealistic expectations for the share of enrollees who should be participating in a successful workforce program: most adult Medicaid enrollees work, and most of those not working are in school or have an illness, disability, or caregiving responsibility that prevents them from working. A successful workforce program should not attempt to reach the majority of enrollees (most of whom are already working), but should instead target outreach to those most likely to benefit from services.

When Montana adopted the Affordable Care Act’s (ACA) Medicaid expansion in 2015, its legislature also authorized its Department of Labor & Industry to administer a workforce promotion program, HELP-Link, for the newly eligible population. HELP-Link provides individualized career planning and job training to low-wage workers and those who are unemployed, with the goal of helping enrollees move up a career ladder.

HELP-Link dedicates significant effort to outreach strategies targeting Medicaid enrollees who may benefit from its services. All newly eligible Medicaid beneficiaries are automatically surveyed about their employment and barriers to work at the point of enrollment and are provided information about HELP-Link workforce programs. The state also sends letters to all Medicaid expansion enrollees about the availabilities of these services.

State workers analyze the surveys completed by individuals who have not yet engaged in training and make outreach calls to offer personalized assistance based on the barriers and needs that each person identified. According to the state, 14,000 individuals have received these outreach calls. The Department of Labor & Industry has also partnered with organizations that regularly interact with Medicaid enrollees — including the state’s hospitals, health insurance assisters, and navigators — to increase awareness of available services.

Enrollees who are interested in enrolling in HELP-Link make an appointment for an in-person assessment with a case manager and complete an individualized employment plan that includes suggested training based on the person’s goals. Once enrolled, participants in HELP-Link can access a wide range of services, such as job seeker workshops and information regarding high-demand sectors. The state also offers significant tuition assistance to individuals interested in enrolling in training for high-demand careers such as health care or manufacturing.

HELP-Link also collaborates with community organizations to provide training for enrollees beyond what the Department of Labor & Industry offers, such as credit history counseling and on-the-job training programs. For training providers whose experience is primarily with people at higher income levels, the state offers trainings in how to effectively engage and support people in and near poverty.

In addition to career services, HELP-Link provides referrals to other state agencies’ services, such as home health aides, child care, and housing, for those with additional barriers to work.[4] Research increasingly shows that the most effective employment programs offer a combination of training and supportive services. Many low-income individuals don’t have the resources to cover child care or transportation costs or to purchase clothes they may need for work. Supportive services can fill these gaps and allow people to succeed at work.[5]

The HELP-Link program demonstrates that many Medicaid enrollees who aren’t working but can work will take advantage of employment services when offered. According to the state, of those who completed HELP-Link surveys, 65 percent went on to receive direct services from staff. In total, 22,000 Montanans have enrolled and received employment services in the program’s first three years.[6] While that figure may seem small compared to Montana’s total Medicaid expansion enrollment — about 94,000[7] — it is sizable once one considers that about two-thirds of Medicaid adult enrollees in Montana already work (most full time), and the large majority of the remainder are either in school or report an illness, disability, or caretaking responsibilities that make it difficult for them to work.[8] This suggests that the HELP-Link program may be reaching a significant share of its target population: people who are not working and do not have severe barriers to work, as well as people who are working but seek better or more stable employment.

Moreover, while the causal impact of the HELP-Link program on employment and wages has not been evaluated, the state reports that HELP-Link participants have high employment rates and are entering high-demand occupations such as registered nurses, nursing assistants, heavy and tractor-trailer truck drivers, and medical record and health information technicians.

In contrast with Montana’s experience, Indiana and Arkansas have expressed disappointment with their voluntary work referral programs and cited low take-up of these programs as part of their justification for imposing work requirements in their Medicaid programs.[9] The apparent difference in results may reflect differences in strategies. While little has been published regarding the outreach efforts of these other states’ workforce programs, Indiana’s 2014 Medicaid waiver proposed simply referring eligible individuals to a website with available employment resources.[10] Similarly, the Arkansas Department of Workforce Services administers a voluntary work referral program for Medicaid expansion enrollees. However, it is not clear whether the state invested in any outreach to these enrollees beyond a notification that the services were available.

It’s likely that Montana’s experience reflects its more intensive approach to outreach and engagement. Medicaid expansion beneficiaries who are unemployed or underemployed may have significant barriers to work that may also make it more difficult for them to engage in workforce training or other services. Montana’s individualized assessment and follow-up, as well as its partnerships with hospitals and other community partners, likely facilitate participation by those who may otherwise miss the opportunity.

Other states may also have unrealistic expectations for the share of enrollees who should be participating in a successful workforce program. As in Montana, most adult Medicaid enrollees in Indiana and Arkansas work, and most of those not working are in school or have an illness, disability, or caregiving responsibility that prevents them from working. A successful workforce program should not be trying to reach the majority of enrollees but should instead target outreach to those most likely to benefit from services.

In contrast with Montana’s approach to workforce promotion, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) recently approved proposals in Kentucky, Indiana, and Arkansas to take Medicaid away from many adults who aren’t working or engaged in other qualifying work activities for a specified number of hours each month, and other states have similar proposals pending with CMS or under discussion. These work requirement policies will cause many low-income adults — including people with mental illness, opioid or other substance use disorders, or serious physical conditions — to lose health coverage, with negative effects on their access to care, health, and financial security.

Work requirements will also likely result in coverage losses among people who are already working substantial hours, but at unstable jobs in industries like retail, restaurant work, home health, and construction where hours fluctuate from month to month and workers often end up with gaps between jobs. Among low-income workers who could be affected by Medicaid work requirements and who worked at least 1,000 hours over the course of a year (more than 80 hours per month on average), 1 in 4 would have been at risk of seeing an interruption in coverage or losing it altogether under an 80-hour-per-month work requirement policy like Kentucky’s, because they did not work 80 hours in every month.[11]

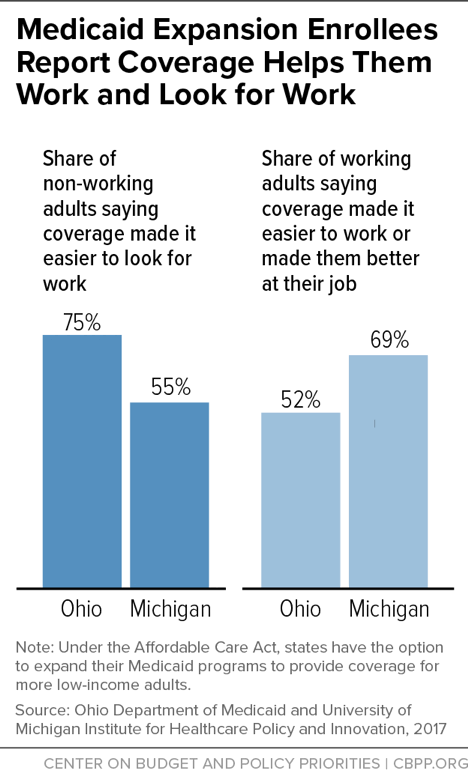

In addition to the harmful impact that losing coverage has on health, health coverage is an important work support. Having health care helps people work and look for work, and taking it away will likely make it harder for some to keep and find work. For example, among non-working adults gaining coverage through the ACA’s Medicaid expansion in Ohio and Michigan, majorities said having health care made it easier to look for work. And among working adults, majorities said coverage made it easier for them to work or made them better at their jobs. (See Figure 1.) Coverage losses from work requirements would likely reverse some of these gains, and could set off a vicious cycle for some enrollees. Health problems are a common cause of job loss among low-wage workers, in part because low-wage jobs often offer little flexibility to take time off due to illness. If job loss also leads to loss of health care and access to treatment, people will only find it harder to get back on their feet.

Montana’s approach avoids these harmful and unintended consequences. By investing in targeted outreach and services for individuals who are able to work but have barriers to finding and holding a job, Montana is spending state funds on services that could actually increase employment and income for low-income people. In contrast, states that are imposing work requirements are in some cases investing hundreds of millions of taxpayer dollars[12] in new systems to monitor and cut Medicaid coverage for people who are not the target of the policy — those who are already working or may never be able to work — with deeply harmful consequences.